Ornithological Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Bird Highlights 2013

FROM PROJECT FEEDERWAtch 2012–13 Focus on citizen science • Volume 9 Winter BirdHighlights Winter npredictability is one constant as each winter Focus on Citizen Science is a publication highlight- ing the contributions of citizen scientists. This is- brings surprises to our feeders. The 2012–13 sue, Winter Bird Highlights 2013, is brought to you by Project FeederWatch, a research and education proj- season broke many regional records with sis- ect of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Bird Studies U Canada. Project FeederWatch is made possible by the kins and nuthatches moving south in record numbers efforts and support of thousands of citizen scientists. to tantalize FeederWatchers across much of the con- Project FeederWatch Staff tinent. This remarkable year also brought a record- David Bonter breaking number of FeederWatchers, with more than Project Leader, USA Janis Dickinson 20,000 participants in the US and Canada combined! Director of Citizen Science, USA Kristine Dobney Whether you’ve been FeederWatching for 26 years or Project Assistant, Canada Wesley Hochachka this is your first season counting, the usual suspects— Senior Research Associate, USA chickadees, juncos, and woodpeckers—always bring Anne Marie Johnson Project Assistant, USA familiarity and enjoyment, as well as valuable data, Rosie Kirton Project Support, Canada even if you don’t observe anything unusual. Whichever Denis Lepage birds arrive at your feeder, we hope they will bring a Senior Scientist, Canada Susan E. Newman sense of wonder that captures your attention. Thanks Project Assistant, USA for sharing your observations and insights with us and, Kerrie Wilcox Project Leader, Canada most importantly, Happy FeederWatching. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

Collation of Brisson's Genera of Birds with Those of Linnaeus

59. 82:01 Article XXVII. COLLATION OF BRISSON'S GENERA OF BIRDS WITH THOSE OF LINNAEUS. BY J. A. ALLEN. CONTENTS. Page. Introduction ....................... 317 Brisson not greatly indebted to Linnaeus. 319 Linneus's indebtedness to Brisson .... .. ... .. 320 Brisson's methods and resources . .. 320 Brisson's genera . 322 Brisson and Linnaeus statistically compared .. .. .. 324 Brisson's 'Ornithologia' compared with the Aves of the tenth edition of Lin- naeus's 'Systema'. 325 Brisson's new genera and their Linnwan equivalents . 327 Brisson's new names for Linnaan genera . 330 Linnaean (1764 and 1766) new names for Brissonian genera . 330 Brissonian names adopted. by Linnaeus . 330 Brissonian names wrongly ascribed to other authors in Sharpe's 'Handlist of Birds'.330 The relation of six Brissonian genera to Linnlean genera . 332 Mergus Linn. and Merganser Briss. 332 Meleagris Linn. and Gallopavo Briss. 332 Alcedo Linn. and Ispida Briss... .. 332 Cotinga Briss. and Ampelis Linn. .. 333 Coracias Linn. and Galgulus Briss.. 333 Tangara Briss. and Tanagra Linn... ... 334 INTRODUCTION. In considering recently certain questions of ornithological nomenclature it became necessary to examine the works of Brisson and Linnaeus in con- siderable detail and this-examination finally led to a careful collation of Brisson's 'Ornithologia,' published in 1760, with the sixth, tenth, and twelfth editions of Linnaeus's 'Systema Naturae,' published respectively in 1748, 1758, and 1766. As every systematic ornithologist has had occasion to learn, Linnaeus's treatment of the class Aves was based on very imperfect knowledge of the suabject. As is well-known, this great systematist was primarily a botanist, secondarily a zoologist, and only incidentally a mammalogist and ornithol- ogist. -

A Birder's Guide to Cook County, Northeastern Minnesota Birding

A Birder’s Guide to Cook County, Northeastern Minnesota This guide will help you find the birds of Cook County, one of the best birding areas in the upper midwest. The shore of Lake Superior and the wildlands of the northeast are natural treasures that are especially rich in birds. Descriptions of the locatoins can be found inside, along with information about how to make the most of your birding during each season of the year. Birding around the year Spring: The migration is always most exciting along the shore of Lake Superior. Spring migration is smaller than fall, but spring specialties include Tundra Swan, Sandhill Crane, Gray-cheeked Thrush, American Tree Sparrow, Harris’ Sparrow, Lapland Longspur and Rusty Blackbird. Boreal species like Black-backed Woodpecker, Boreal Owl and Northern Saw-whet Owl begin nesting during spring, which can begin as early as March and extend until June. Summer: In summer the excitement moves inland where specialties inclue Common Loon, American Black Duck, Bald Eagle, Ruffled Grouse, American Woodcock, Black-billed Cuckoo, Barred Owl, Northern Saw- whet Owl, Whip-poor-will, Olive-sided, Yellow-bellied, and Alder Flycatchers, Gray Jay, Boreal Chickadee, Winter and Sedge Wrens, 20 species of warblers, Le Conte’s Sparrow, and Evening Grosbeak. The summer breeding season extends from late May through early August. Autumn: the fall migration along the Norht Shore of Lake Superior is not to be missed! Beginning with the sight of thousands of Common Nighthawks in late August, the sheer quantity of birds moving down the shore makes this area a world-class migration route. -

Summary Data

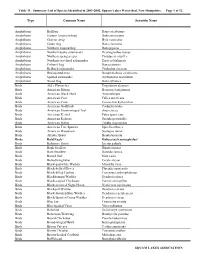

Table 11. Summary List of Species Identified in 2001-2002, Squam Lakes Watershed, New Hampshire. Page 1 of 12 Type Common Name Scientific Name Amphibians Bullfrog Rana catesbeiana Amphibians Eastern American toad Bufo americanus Amphibians Gray treefrog Hyla versicolor Amphibians Green frog Rana clamitans Amphibians Northern leopard frog Rana pipiens Amphibians Northern dusky salamander Desmognathus fuscus Amphibians Northern spring peeper Pseudacris crucifer Amphibians Northern two-lined salamander Eurycea bislineata Amphibians Pickerel frog Rana palustris Amphibians Redback salamander Plethodon cinereus Amphibians Red-spotted newt Notophthalmus viridescens Amphibians Spotted salamander Ambystoma maculatum Amphibians Wood frog Rana sylvatica Birds Alder Flycatcher Empidonax alnorum Birds American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus Birds American Black Duck Anas rubripes Birds American Coot Fulica americana Birds American Crow Corvus brachyrhynchos Birds American Goldfinch Carduelis tristis Birds American Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Birds American Kestrel Falco sparverius Birds American Redstart Setophaga ruticilla Birds American Robin Turdus migratorius Birds American Tree Sparrow Spizella arborea Birds American Woodcock Scolopax minor Birds Atlantic Brant Branta bernicla Birds Bald Eagle* Haliaeetus leucocephalus* Birds Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula Birds Bank Swallow Riparia riparia Birds Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica Birds Barred Owl Strix varia Birds Belted Kingfisher Ceryle alcyon Birds Black-and-white Warbler Mniotilta varia Birds -

Diversity and Clade Ages of West Indian Hummingbirds and the Largest Plant Clades Dependent on Them: a 5–9 Myr Young Mutualistic System

bs_bs_banner Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2015, 114, 848–859. With 3 figures Diversity and clade ages of West Indian hummingbirds and the largest plant clades dependent on them: a 5–9 Myr young mutualistic system STEFAN ABRAHAMCZYK1,2*, DANIEL SOUTO-VILARÓS1, JIMMY A. MCGUIRE3 and SUSANNE S. RENNER1 1Department of Biology, Institute for Systematic Botany and Mycology, University of Munich (LMU), Menzinger Str. 67, 80638 Munich, Germany 2Department of Biology, Nees Institute of Plant Biodiversity, University of Bonn, Meckenheimer Allee 170, 53113 Bonn, Germany 3Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, 3101 Valley Life Sciences Building, Berkeley, CA 94720-3160, USA Received 23 September 2014; revised 10 November 2014; accepted for publication 12 November 2014 We analysed the geographical origins and divergence times of the West Indian hummingbirds, using a large clock-dated phylogeny that included 14 of the 15 West Indian species and statistical biogeographical reconstruction. We also compiled a list of 101 West Indian plant species with hummingbird-adapted flowers (90 of them endemic) and dated the most species-rich genera or tribes, with together 41 hummingbird-dependent species, namely Cestrum (seven spp.), Charianthus (six spp.), Gesnerieae (75 species, c. 14 of them hummingbird-pollinated), Passiflora (ten species, one return to bat-pollination) and Poitea (five spp.), to relate their ages to those of the bird species. Results imply that hummingbirds colonized the West Indies at least five times, from 6.6 Mya onwards, coming from South and Central America, and that there are five pairs of sister species that originated within the region. -

Winter Bird Highlights 2015, Is Brought to You by U.S

Winter Bird Highlights FROM PROJECT FEEDERWATCH 2014–15 FOCUS ON CITIZEN SCIENCE • VOLUME 11 Focus on Citizen Science is a publication highlight- FeederWatch welcomes new ing the contributions of citizen scientists. This is- sue, Winter Bird Highlights 2015, is brought to you by U.S. project assistant Project FeederWatch, a research and education proj- ect of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Bird Studies Canada. Project FeederWatch is made possible by the e are pleased to have a new efforts and support of thousands of citizen scientists. Wteam member on board! Meet Chelsea Benson, a new as- Project FeederWatch Staff sistant for Project FeederWatch. Chelsea will also be assisting with Cornell Lab of Ornithology NestWatch, another Cornell Lab Janis Dickinson citizen-science project. She will Director of Citizen Science be responding to your emails and Emma Greig phone calls and helping to keep Project Leader and Editor the website and social media pages Anne Marie Johnson Project Assistant up-to-date. Chelsea comes to us with a back- Chelsea Benson Project Assistant ground in environmental educa- Wesley Hochachka tion and conservation. She has worked with schools, community Senior Research Associate organizations, and local governments in her previous positions. Diane Tessaglia-Hymes She incorporated citizen science into her programming and into Design Director regional events like Day in the Life of the Hudson River. Chelsea holds a dual B.A. in psychology and English from Bird Studies Canada Allegheny College and an M.A. in Social Science, Environment Kerrie Wilcox and Community, from Humboldt State University. Project Leader We are excited that Chelsea has brought her energy and en- Rosie Kirton thusiasm to the Cornell Lab, where she will no doubt mobilize Project Support even more people to monitor bird feeders (and bird nests) for Kristine Dobney Project Assistant science. -

Birds of Anchorage Checklist

ACCIDENTAL, CASUAL, UNSUBSTANTIATED KEY THRUSHES J F M A M J J A S O N D n Casual: Occasionally seen, but not every year Northern Wheatear N n Accidental: Only one or two ever seen here Townsend’s Solitaire N X Unsubstantiated: no photographic or sample evidence to support sighting Gray-cheeked Thrush N W Listed on the Audubon Alaska WatchList of declining or threatened species Birds of Swainson’s Thrush N Hermit Thrush N Spring: March 16–May 31, Summer: June 1–July 31, American Robin N Fall: August 1–November 30, Winter: December 1–March 15 Anchorage, Alaska Varied Thrush N W STARLINGS SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER SPECIES SPECIES SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER European Starling N CHECKLIST Ross's Goose Vaux's Swift PIPITS Emperor Goose W Anna's Hummingbird The Anchorage area offers a surprising American Pipit N Cinnamon Teal Costa's Hummingbird Tufted Duck Red-breasted Sapsucker WAXWINGS diversity of habitat from tidal mudflats along Steller's Eider W Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Bohemian Waxwing N Common Eider W Willow Flycatcher the coast to alpine habitat in the Chugach BUNTINGS Ruddy Duck Least Flycatcher John Schoen Lapland Longspur Pied-billed Grebe Hammond's Flycatcher Mountains bordering the city. Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel Eastern Kingbird BOHEMIAN WAXWING Snow Bunting N Leach's Storm-Petrel Western Kingbird WARBLERS Pelagic Cormorant Brown Shrike Red-faced Cormorant W Cassin's Vireo Northern Waterthrush N For more information on Alaska bird festivals Orange-crowned Warbler N Great Egret Warbling Vireo Swainson's Hawk Red-eyed Vireo and birding maps for Anchorage, Fairbanks, Yellow Warbler N American Coot Purple Martin and Kodiak, contact Audubon Alaska at Blackpoll Warbler N W Sora Pacific Wren www.AudubonAlaska.org or 907-276-7034. -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, Version 2018-07-24

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, version 2018-07-24 Kenai National Wildlife Refuge biology staff July 24, 2018 2 Cover image: map of 16,213 georeferenced occurrence records included in the checklist. Contents Contents 3 Introduction 5 Purpose............................................................ 5 About the list......................................................... 5 Acknowledgments....................................................... 5 Native species 7 Vertebrates .......................................................... 7 Invertebrates ......................................................... 55 Vascular Plants........................................................ 91 Bryophytes ..........................................................164 Other Plants .........................................................171 Chromista...........................................................171 Fungi .............................................................173 Protozoans ..........................................................186 Non-native species 187 Vertebrates ..........................................................187 Invertebrates .........................................................187 Vascular Plants........................................................190 Extirpated species 207 Vertebrates ..........................................................207 Vascular Plants........................................................207 Change log 211 References 213 Index 215 3 Introduction Purpose to avoid implying -

The Birds of New York State

__ Common Goldeneye RAILS, GALLINULES, __ Baird's Sandpiper __ Black-tailed Gull __ Black-capped Petrel Birds of __ Barrow's Goldeneye AND COOTS __ Little Stint __ Common Gull __ Fea's Petrel __ Smew __ Least Sandpiper __ Short-billed Gull __ Cory's Shearwater New York State __ Clapper Rail __ Hooded Merganser __ White-rumped __ Ring-billed Gull __ Sooty Shearwater __ King Rail © New York State __ Common Merganser __ Virginia Rail Sandpiper __ Western Gull __ Great Shearwater Ornithological __ Red-breasted __ Corn Crake __ Buff-breasted Sandpiper __ California Gull __ Manx Shearwater Association Merganser __ Sora __ Pectoral Sandpiper __ Herring Gull __ Audubon's Shearwater Ruddy Duck __ Semipalmated __ __ Iceland Gull __ Common Gallinule STORKS Sandpiper www.nybirds.org GALLINACEOUS BIRDS __ American Coot __ Lesser Black-backed __ Wood Stork __ Northern Bobwhite __ Purple Gallinule __ Western Sandpiper Gull FRIGATEBIRDS DUCKS, GEESE, SWANS __ Wild Turkey __ Azure Gallinule __ Short-billed Dowitcher __ Slaty-backed Gull __ Magnificent Frigatebird __ Long-billed Dowitcher __ Glaucous Gull __ Black-bellied Whistling- __ Ruffed Grouse __ Yellow Rail BOOBIES AND GANNETS __ American Woodcock Duck __ Spruce Grouse __ Black Rail __ Great Black-backed Gull __ Brown Booby __ Wilson's Snipe __ Fulvous Whistling-Duck __ Willow Ptarmigan CRANES __ Sooty Tern __ Northern Gannet __ Greater Prairie-Chicken __ Spotted Sandpiper __ Bridled Tern __ Snow Goose __ Sandhill Crane ANHINGAS __ Solitary Sandpiper __ Least Tern __ Ross’s Goose __ Gray Partridge -

Persistence of Host Defence Behaviour in the Absence of Avian Brood

Downloaded from http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on February 12, 2015 Biol. Lett. (2011) 7, 670–673 selection is renewed, and therefore may accelerate an doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0268 evolutionary response to the selection pressure. Published online 14 April 2011 We examined the extent to which a behavioural Animal behaviour defence persists in the absence of selection from avian brood parasitism. The interactions between avian brood parasites and their hosts are ideal for Persistence of host determining the fate of adaptations once selection has been relaxed, owing to shifting distributions of defence behaviour in the hosts and parasites [5,6] or the avoidance of well- defended hosts by parasites [7,8]. Host defences such absence of avian brood as rejection of parasite eggs may be lost in the absence parasitism of selection if birds reject their oddly coloured eggs [9,10], but are more likely to be retained because Brian D. Peer1,2,3,*, Michael J. Kuehn2,4, these behaviours may never be expressed in circum- Stephen I. Rothstein2 and Robert C. Fleischer1 stances other than parasitism [2,3]. Whether host 1Center for Conservation and Evolutionary Genetics, defences persist in the absence of brood parasitism is Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, critical to long-term avian brood parasite–host coevolu- Smithsonian Institution, PO Box 37012, MRC 5503, Washington, tion. If defences decline quickly, brood parasites can DC 20013-7012, USA alternate between well-defended hosts and former 2Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA hosts that have lost most of their defences, owing to the 3Department of Biological Sciences, Western Illinois University, Macomb, costs of maintaining them once parasitism has ceased, IL 61455, USA 4 or follow what has been termed the ‘coevolutionary Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology, 439 Calle San Pablo, cycles’ model of host–brood parasite coevolution [3]. -

Birds Topics in Biodiversity

Topics in Biodiversity The Encyclopedia of Life is an unprecedented effort to gather scientific knowledge about all life on earth- multimedia, information, facts, and more. Learn more at eol.org. Birds Authors: Jeff Betz, Science Communication Program, Laurentian University Cyndy Parr, Encyclopedia of Life, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution Photo credit: Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) by Mike Baird, Wikimedia Commons. CC BY Defining Birds Birds form a class of animals that includes over 10,000 species worldwide (Clements 2007). These species were traditionally divided into 30 orders (Peters et al. 1931–1987) but more recent lists (in part based on molecular studies) group birds into 23 to 40 orders (Clement 2007, Gill and Donsker 2012). Passeriformes, commonly called perching birds or songbirds, are the most diverse order. Birds range in size from the Small Bee Hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae) to the large flightless Ostrich (Struthio camelus). Compared to mammals, which range in size from shrews to the blue whale, birds that fly have a restricted size range. This restriction is imposed by the mechanical constraints of flight: the larger the bird the more muscular energy needed to stay airborne. Flightless birds have no such limit. Some extinct flightless birds, such as Diatrymia gigantean, were 7 feet tall, and the giant carnivorous ground birds of South America, the phororhacids, were also large. Habitat, Physiological Characteristics, and Behavior Birds live in a wide range of environments, from tropical rainforests to the polar regions, though no one species is as widespread as Homo sapiens. The Barn Owl (Tyto alba) is one of the more widespread 1 species, found on every continent except Australia and Antarctica.