The Late Qing Dynasty (1898-1911)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

The Ballad of Mulan Report and Poem

Wolfe !1 Brady Wolfe Dr. Christensen CHIN 343 December 8, 2015 Mulan China to me for many years was defined by the classic story of Mulan. It was a foreign land as far away from me as anything I could fathom, yet it was so fascinating to me that I would of- ten even pretend I could speak Chinese, and I still remember the excitement I felt when as a young child I first watched Disney’s retelling of Mulan. I watched it over and over again, and when I went to China for the first time, I was honestly quite surprised to find that today’s China was quite different from my childhood imaginations inspired by that movie. For this reason, when I discovered that the legend of Mulan originates from an ancient Chinese poem, I decided it would be appropriate and enjoyable for me to choose this poem as the subject of my translation and research project. The core of this project is my own translation of the classic poem, and addi- tionally I will discuss a little bit about the history of the poem, and analyze its structure and for- mat. The original source for the poem of Mulan has been lost, but it was transcribed into the Music Bureau Collections, an anthology by Guo Maoqing put together sometime during the Song dy- nasty around the 11th or 12th century A.D., and a note is given by Guo saying that the source from which it was taken and transcribed into the collection was a compilation made during the beginning of the Tang dynasty, more or less 6th century A.D., called the Musical Records of Old and New, (Project Gutenberg). -

Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis

arts Article Cultural “Authenticity” as a Conflict-Ridden Hypotext: Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis Zhuoyi Wang Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY 13323, USA; [email protected] Received: 6 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 10 July 2020 Abstract: Disney’s Mulan (1998) has generated much scholarly interest in comparing the film with its hypotext: the Chinese legend of Mulan. While this comparison has produced meaningful criticism of the Orientalism inherent in Disney’s cultural appropriation, it often ironically perpetuates the Orientalist paradigm by reducing the legend into a unified, static entity of the “authentic” Chinese “original”. This paper argues that the Chinese hypotext is an accumulation of dramatically conflicting representations of Mulan with no clear point of origin. It analyzes the Republican-era film adaptation Mulan Joins the Army (1939) as a cultural palimpsest revealing attributes associated with different stages of the legendary figure’s millennium-long intertextual metamorphosis, including a possibly nomadic woman warrior outside China proper, a Confucian role model of loyalty and filial piety, a Sinitic deity in the Sino-Barbarian dichotomy, a focus of male sexual fantasy, a Neo-Confucian exemplar of chastity, and modern models for women established for antagonistic political agendas. Similar to the previous layers of adaptation constituting the hypotext, Disney’s Mulan is simply another hypertext continuing Mulan’s metamorphosis, and it by no means contains the most dramatic intertextual change. Productive criticism of Orientalist cultural appropriations, therefore, should move beyond the dichotomy of the static East versus the change-making West, taking full account of the immense hybridity and fluidity pulsing beneath the fallacy of a monolithic cultural “authenticity”. -

The Real Story of Mulan By: the Scribe on Friday, June 17, 2011

The Real Story of Mulan By: The Scribe on Friday, June 17, 2011 Many people have seen the Disney movie Mulan and do not realize that it is actually telling the story of an ancient Chinese poem titled the Ballad of Mulan. Because it is a legend, it is unknown when Mulan may have lived although she was believed to have lived during theNorthern Wei dynasty which lasted from 386CE to 534CE. In the movie, Mulan is depicted as being unskilled with weapons. The “real” Mulan, on the other hand, was said to have practiced with many different weapons. The area in which she was believed to have lived was known for practicing martial arts such as Kung Fu and for being skilled with the sword. In the legend, the real Mulan (whose name was actually Hua Mulan) rode horses and shooting arrows. In the movie as well as in the poem, there was no male child. This caused problems when the Emperor (or Khan as he is called in the poem) began to call up troops to fight the invading Mongol and nomadic tribes. If there had been a son he could have gone in his father’s place as it was only up to the family to provide one man to fight. Whether it was the father or the son did not matter; all they needed to do was provide one person to join the army. As in the Disney movie, Mulan chose to enlist in her father’s place as he was too old to fight. At the age of eighteen she joined the army and prepared to fight against the Mongolian and nomadic tribes that wanted to invade China. -

三國演義 Court of Liu Bei 劉備法院

JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms 三國演義 Court of Liu Bei 劉備法院 Crisis Directors: Matthew Owens, Charles Miller Emails: [email protected], [email protected] Chair: Isis Mosqueda Email: [email protected] Single-Delegate: Maximum 20 Positions Table of Contents: 1. Title Page (Page 1) 2. Table of Contents (Page 2) 3. Chair Introduction Page (Page 3) 4. Crisis Director Introduction Pages (Pages 4-5) 5. Intro to JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Pages 6-9) 6. Intro to Liu Bei (Pages 10-11) 7. Topic History: Jing Province (Pages 12-14) 8. Perspective (Pages 15-16) 9. Current Situation (Pages 17-19) 10. Maps of the Middle Kingdom / China (Pages 20-21) 11. Liu Bei’s Domain Statistics (Page 22) 12. Guiding Questions (Pages 22-23) 13. Resources for Further Research (Page 23) 14. Works Cited (Pages 24-) Dear delegates, I am honored to welcome you all to the Twenty Ninth Mid-Atlantic Simulation of the United Nations Conference, and I am pleased to welcome you to JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Everyone at MASUN XXIX have been working hard to ensure that this committee and this conference will be successful for you, and we will continue to do so all weekend. My name is Isis Mosqueda and I am recent George Mason Alumna. I am also a former GMU Model United Nations president, treasurer and member, as well as a former MASUN Director General. I graduated last May with a B.A. in Government and International politics with a minor in Legal Studies. I am currently an academic intern for the Smithsonian Institution, working for the National Air and Space Museum’s Education Department, and a substitute teacher for Loudoun County Public Schools. -

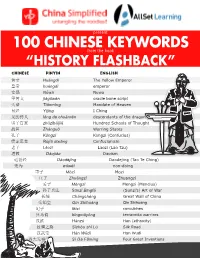

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China

Material and Symbolic Economies: Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Tian, Xiaofei. "4 Material and Symbolic Economies: Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China." In A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, pp. 135-186. Brill, 2015. Published Version doi:10.1163/9789004292123_006 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:29037391 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Material and Symbolic Economies_Tian Material and Symbolic Economies: Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China* Xiaofei Tian Harvard University This paper examines a group of letters in early medieval China, specifically from the turn of the third century and from the early sixth century, about gift giving and receiving. Gift-giving is one of the things that stand at the center of social relationships across many cultures. “The gift imposes an identity upon the giver as well as the receiver.”1 It is both productive of social relationships and affirms them; it establishes and clarifies social status, displays power, strengthens alliances, and creates debt and obligations. This was particularly true in the chaotic period following the collapse of the Han empire at the turn of the third century, often referred to by the reign title of the last Han emperor as the Jian’an 建安 era (196-220). -

Summarized in China Daily Sept 9, 2015

Reactors deal Date with history What depreciation? Renowned scrolled painting Chinese tourists are unfazed by Domestic nuclear power group unrolled at the Palace Museum the yuan’s drop in global value seals agreement with Kenya > p13 > CHINA, PAGE 3 > LIFE, PAGE 7 WEDNESDAY, September 9, 2015 chinadailyusa.com $1 DIPLOMACY For Xi’s visit, mutual trust a must: expert Vogel says momentum in dialogue can best benefi t By REN QI in New York [email protected] The coming state visit of President The boost Xi Jinping to the US and his meeting with his US counterpart President of mutual Barack Obama will be a milestone and mutual trust will be the biggest issue trust may and may be the largest contribution Xi’s visit can make, said Ezra Vogel, a be the professor emeritus of the Asia Center at Harvard University. largest “The boost of mutual trust may be the largest contribution of Xi’s visit contribution of Xi’s visit to Sino-US relation,” Vogel said in to Sino-US relation.” an interview with Chinese media on Monday. “Xi had some connection Ezra Vogel, professor emeritus of the and established some friendship with Asia Center at Harvard University local residents in Iowa during his visit in 1985 and in 2012, and this is the spe- cial bridge between Xi and ordinary US people.” Security Advisor, visited Beijing in Vogel predicted the two leaders August and met with President Xi would talk about some big concerns, and other government offi cials. Rice such as Diaoyu Island, the South Chi- showed a positive attitude during na Sea, the environment and cyber- the visit, and expressed the wish to security. -

The Chinese State in Ming Society

The Chinese State in Ming Society The Ming dynasty (1368–1644), a period of commercial expansion and cultural innovation, fashioned the relationship between the present-day state and society in China. In this unique collection of reworked and illustrated essays, one of the leading scholars of Chinese history re-examines this relationship and argues that, contrary to previous scholarship, which emphasized the heavy hand of the state, it was radical responses within society to changes in commercial relations and social networks that led to a stable but dynamic “constitution” during the Ming dynasty. This imaginative reconsideration of existing scholarship also includes two essays first published here and a substantial introduction, and will be fascinating reading for scholars and students interested in China’s development. Timothy Book is Principal of St. John’s College, University of British Colombia. Critical Asian Scholarship Edited by Mark Selden, Binghamton and Cornell Universities, USA The series is intended to showcase the most important individual contributions to scholarship in Asian Studies. Each of the volumes presents a leading Asian scholar addressing themes that are central to his or her most significant and lasting contribution to Asian studies. The series is committed to the rich variety of research and writing on Asia, and is not restricted to any particular discipline, theoretical approach or geographical expertise. Southeast Asia A testament George McT.Kahin Women and the Family in Chinese History Patricia Buckley Ebrey -

How Poetry Became Meditation in Late-Ninth-Century China

how poetry became meditation Asia Major (2019) 3d ser. Vol. 32.2: 113-151 thomas j. mazanec How Poetry Became Meditation in Late-Ninth-Century China abstract: In late-ninth-century China, poetry and meditation became equated — not just meta- phorically, but as two equally valid means of achieving stillness and insight. This article discusses how several strands in literary and Buddhist discourses fed into an assertion about such a unity by the poet-monk Qiji 齊己 (864–937?). One strand was the aesthetic of kuyin 苦吟 (“bitter intoning”), which involved intense devotion to poetry to the point of suffering. At stake too was the poet as “fashioner” — one who helps make and shape a microcosm that mirrors the impersonal natural forces of the macrocosm. Jia Dao 賈島 (779–843) was crucial in popularizing this sense of kuyin. Concurrently, an older layer of the literary-theoretical tradition, which saw the poet’s spirit as roaming the cosmos, was also given new life in late Tang and mixed with kuyin and Buddhist meditation. This led to the assertion that poetry and meditation were two gates to the same goal, with Qiji and others turning poetry writing into the pursuit of enlightenment. keywords: Buddhism, meditation, poetry, Tang dynasty ometime in the early-tenth century, not long after the great Tang S dynasty 唐 (618–907) collapsed and the land fell under the control of regional strongmen, a Buddhist monk named Qichan 棲蟾 wrote a poem to another monk. The first line reads: “Poetry is meditation for Confucians 詩為儒者禪.”1 The line makes a curious claim: the practice Thomas Mazanec, Dept. -

(TJDBPS01): Study Protocol for a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial

Total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy (TJDBPS01): study protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Hang Zhang1, Junfang Zhao1, Yechen Feng1, Rufu Chen2, Xuemin Chen3, Wei Cheng4, Dewei Li5, Jingdong Li6, Xiaobing Huang7, Heguang Huang13, Deyu Li14, Jing Li7, Jianhua Liu8, Jun Liu9, Yahui Liu10, Zhijian Tan11, Xinmin Yin4, Wenxing Zhao12, Yahong Yu1, Min Wang1✉, Renyi Qin1 ✉. Minimally Invasive Pancreas Treatment Group in the Pancreatic Disease Branch of China’s International Exchange and Promotion Association for Medicine and Healthcare. 1 Department of Biliary–Pancreatic Surgery, Affiliated Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei 430030, China. 2 Department of Surgery, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510120, China. 3 Department of Pancreaticobiliary Surgery, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Jiangsu 213000, China. 4 Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Hunan Normal University, Changsha, Hunan 410000, China. 5 Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 404100, China. 6 Department of Pancreatico-Hepatobiliary Surgery, Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College, Sichuan 637000, China. 7 Department of Pancreatico-Hepatobiliary Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Army Medical University, PLA, Chongqing 404100, China. 8 Department of Hepato–Pancreato–Biliary Surgery, The Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, Hebei 050017, China. 9 Department of Hepato–Pancreato–Biliary Surgery, Shandong Provincial Hospital, Shandong 250000, China. 10 Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, The First Hospital of Jilin University, 71 Xinmin Street, Changchun, Jilin 130021, China. 11 Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, Guangdong Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510120, China. -

East Asian Languages & Civilization (EALC)

East Asian Languages & Civilization (EALC) 1 EALC 008 East Asian Religions EAST ASIAN LANGUAGES & This course will introduce students to the diverse beliefs, ideas, and practices of East Asia's major religious traditions: Buddhism, CIVILIZATION (EALC) Confucianism, Daoism, Shinto, Popular Religion, as well as Asian forms of Islam and Christianity. As religious identity in East Asia is often EALC 001 Introduction to Chinese Civilization fluid and non-sectarian in nature, there religious traditions will not be Survey of the civilization of China from prehistoric times to the present. investigated in isolation. Instead, the course will adopt a chronological For BA Students: History and Tradition Sector and geographical approach, examining the spread of religious ideas and Taught by: Goldin, Atwood, Smith, Cheng practices across East Asia and the ensuing results of these encounters. Course usually offered in fall term The course will be divided into three units. Unit one will cover the Activity: Lecture religions of China. We will begin by discussing early Chinese religion 1.0 Course Unit and its role in shaping the imperial state before turning to the arrival EALC 002 Introduction to Japanese Civilization of Buddhism and its impact in the development of organized Daoism, Survey of the civilization of Japan from prehistoric times to the present. as well as local religion. In the second unit, we will turn eastward into For BA Students: History and Tradition Sector Korea and Japan. After examining the impact of Confucianism and Course usually offered in spring term Buddhism on the religious histories of these two regions, we will proceed Activity: Lecture to learn about the formation of new schools of Buddhism, as well as 1.0 Course Unit the rituals and beliefs associated with Japanese Shinto and Korean Notes: Fulfills Cross-Cultural Analysis Shamanism.