The Politics of Place-Making in the Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

Daoxuan's vision of Jetavana: Imagining a utopian monastery in early Tang Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tan, Ai-Choo Zhi-Hui Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 09:09:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280212 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are In typewriter face, while others may be from any type of connputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 DAOXUAN'S VISION OF JETAVANA: IMAGINING A UTOPIAN MONASTERY IN EARLY TANG by Zhihui Tan Copyright © Zhihui Tan 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 UMI Number: 3073263 Copyright 2002 by Tan, Zhihui Ai-Choo All rights reserved. -

Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880S-1940S

Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hashimoto, Satoru. 2014. Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13064962 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s A dissertation presented by Satoru Hashimoto to The Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of East Asian Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2014 ! ! © 2014 Satoru Hashimoto All rights reserved. ! ! Dissertation Advisor: Professor David Der-Wei Wang Satoru Hashimoto Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s Abstract This dissertation examines how modern literature in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan in the late-nineteenth to the early-twentieth centuries was practiced within contexts of these countries’ deeply interrelated literary traditions. -

The Ballad of Mulan Report and Poem

Wolfe !1 Brady Wolfe Dr. Christensen CHIN 343 December 8, 2015 Mulan China to me for many years was defined by the classic story of Mulan. It was a foreign land as far away from me as anything I could fathom, yet it was so fascinating to me that I would of- ten even pretend I could speak Chinese, and I still remember the excitement I felt when as a young child I first watched Disney’s retelling of Mulan. I watched it over and over again, and when I went to China for the first time, I was honestly quite surprised to find that today’s China was quite different from my childhood imaginations inspired by that movie. For this reason, when I discovered that the legend of Mulan originates from an ancient Chinese poem, I decided it would be appropriate and enjoyable for me to choose this poem as the subject of my translation and research project. The core of this project is my own translation of the classic poem, and addi- tionally I will discuss a little bit about the history of the poem, and analyze its structure and for- mat. The original source for the poem of Mulan has been lost, but it was transcribed into the Music Bureau Collections, an anthology by Guo Maoqing put together sometime during the Song dy- nasty around the 11th or 12th century A.D., and a note is given by Guo saying that the source from which it was taken and transcribed into the collection was a compilation made during the beginning of the Tang dynasty, more or less 6th century A.D., called the Musical Records of Old and New, (Project Gutenberg). -

Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis

arts Article Cultural “Authenticity” as a Conflict-Ridden Hypotext: Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis Zhuoyi Wang Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY 13323, USA; [email protected] Received: 6 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 10 July 2020 Abstract: Disney’s Mulan (1998) has generated much scholarly interest in comparing the film with its hypotext: the Chinese legend of Mulan. While this comparison has produced meaningful criticism of the Orientalism inherent in Disney’s cultural appropriation, it often ironically perpetuates the Orientalist paradigm by reducing the legend into a unified, static entity of the “authentic” Chinese “original”. This paper argues that the Chinese hypotext is an accumulation of dramatically conflicting representations of Mulan with no clear point of origin. It analyzes the Republican-era film adaptation Mulan Joins the Army (1939) as a cultural palimpsest revealing attributes associated with different stages of the legendary figure’s millennium-long intertextual metamorphosis, including a possibly nomadic woman warrior outside China proper, a Confucian role model of loyalty and filial piety, a Sinitic deity in the Sino-Barbarian dichotomy, a focus of male sexual fantasy, a Neo-Confucian exemplar of chastity, and modern models for women established for antagonistic political agendas. Similar to the previous layers of adaptation constituting the hypotext, Disney’s Mulan is simply another hypertext continuing Mulan’s metamorphosis, and it by no means contains the most dramatic intertextual change. Productive criticism of Orientalist cultural appropriations, therefore, should move beyond the dichotomy of the static East versus the change-making West, taking full account of the immense hybridity and fluidity pulsing beneath the fallacy of a monolithic cultural “authenticity”. -

Silk Road Fashion, China. the City and a Gate, the Pass and a Road – Four Components That Make Luoyang the Capital of the Silk Roads Between 1St and 7Th Century AD

https://publications.dainst.org iDAI.publications ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Dies ist ein digitaler Sonderdruck des Beitrags / This is a digital offprint of the article Patrick Wertmann Silk Road Fashion, China. The City and a Gate, the Pass and a Road – Four components that make Luoyang the capital of the Silk Roads between 1st and 7th century AD. The year 2018 aus / from e-Forschungsberichte Ausgabe / Issue Seite / Page 19–37 https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb/2178/6591 • urn:nbn:de:0048-dai-edai-f.2019-0-2178 Verantwortliche Redaktion / Publishing editor Redaktion e-Jahresberichte und e-Forschungsberichte | Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Weitere Informationen unter / For further information see https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb ISSN der Online-Ausgabe / ISSN of the online edition ISSN der gedruckten Ausgabe / ISSN of the printed edition Redaktion und Satz / Annika Busching ([email protected]) Gestalterisches Konzept: Hawemann & Mosch Länderkarten: © 2017 www.mapbox.com ©2019 Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Zentrale, Podbielskiallee 69–71, 14195 Berlin, Tel: +49 30 187711-0 Email: [email protected] / Web: dainst.org Nutzungsbedingungen: Die e-Forschungsberichte 2019-0 des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts stehen unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung – Nicht kommerziell – Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 International. Um eine Kopie dieser Lizenz zu sehen, besuchen Sie bitte http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ -

The Real Story of Mulan By: the Scribe on Friday, June 17, 2011

The Real Story of Mulan By: The Scribe on Friday, June 17, 2011 Many people have seen the Disney movie Mulan and do not realize that it is actually telling the story of an ancient Chinese poem titled the Ballad of Mulan. Because it is a legend, it is unknown when Mulan may have lived although she was believed to have lived during theNorthern Wei dynasty which lasted from 386CE to 534CE. In the movie, Mulan is depicted as being unskilled with weapons. The “real” Mulan, on the other hand, was said to have practiced with many different weapons. The area in which she was believed to have lived was known for practicing martial arts such as Kung Fu and for being skilled with the sword. In the legend, the real Mulan (whose name was actually Hua Mulan) rode horses and shooting arrows. In the movie as well as in the poem, there was no male child. This caused problems when the Emperor (or Khan as he is called in the poem) began to call up troops to fight the invading Mongol and nomadic tribes. If there had been a son he could have gone in his father’s place as it was only up to the family to provide one man to fight. Whether it was the father or the son did not matter; all they needed to do was provide one person to join the army. As in the Disney movie, Mulan chose to enlist in her father’s place as he was too old to fight. At the age of eighteen she joined the army and prepared to fight against the Mongolian and nomadic tribes that wanted to invade China. -

Zen) Buddhism

THE SPREAD OF CHAN (ZEN) BUDDHISM T. Grif\ th Foulk (Sarah Lawrence College, New York) 1. Introduction This chapter deals with the development and spread of the so-called Chan School of Buddhism in China, Japan, and the West. In its East Asian setting, at least, the spread of Chan must be viewed rather dif- ferently than the spread of Buddhism as a whole, for by all accounts (both traditional and modern) Chan was a movement that initially ] ourished within, or (as some would have it) in reaction against, a Buddhist monastic order that had already been active in China for a number of centuries. By the same token, at the times when the Chan movement spread to Korea and Japan, it did not appear as the har- binger of Buddhism itself, which was already well established in those countries, but rather as the most recent in a series of importations of Buddhism from China. The situation in the West, of course, is much different. Here, Chan—usually referred to (using the Japanese pronun- ciation) as Zen—has indeed been at the vanguard of the spread of Buddhism as a whole. I begin this chapter by re] ecting on what we (modern scholars) mean when we speak of the spread of Buddhism, contrasting that with a few of the traditional ways in which Asian Buddhists themselves, from an insider’s or normative point of view, have conceived the transmission of the Buddha’s teachings (Skt. buddhadharma, Chin. fofa 佛法). I then turn to the main topic: the spread of Chan. -

Beyond Buddhist Apology the Political Use of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography Beyond Buddhist Apology The Political Use of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty (r.502-549) Tom De Rauw ii To my daughter Pauline, the most wonderful distraction one could ever wish for and to my grandfather, a cakravartin who ruled his own private universe iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Although the writing of a doctoral dissertation is an individual endeavour in nature, it certainly does not come about from the efforts of one individual alone. The present dissertation owes much of its existence to the help of the many people who have guided my research over the years. My heartfelt thanks, first of all, go to Dr. Ann Heirman, who supervised this thesis. Her patient guidance has been of invaluable help. Thanks also to Dr. Bart Dessein and Dr. Christophe Vielle for their help in steering this thesis in the right direction. I also thank Dr. Chen Jinhua, Dr. Andreas Janousch and Dr. Thomas Jansen for providing me with some of their research and for sharing their insights with me. My fellow students Dr. Mathieu Torck, Leslie De Vries, Mieke Matthyssen, Silke Geffcken, Evelien Vandenhaute, Esther Guggenmos, Gudrun Pinte and all my good friends who have lent me their listening ears, and have given steady support and encouragement. To my wife, who has had to endure an often absent-minded husband during these first years of marriage, I acknowledge a huge debt of gratitude. She was my mentor in all but the academic aspects of this thesis. -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

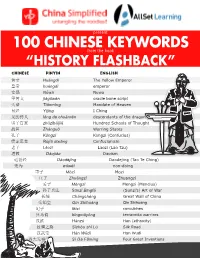

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

Another Look at Early Chan: Daoxuan, Bodhidharma, and the Three Levels Movement

T’OUNGT’OUNG PAO PAO T’oung Pao 94 (2008) 49-114 www.brill.nl/tpao Another Look at Early Chan: Daoxuan, Bodhidharma, and the Three Levels Movement Eric Greene University of California, Berkeley Abstract As one of the earliest records pertaining to Bodhidharma, Daoxuan’s Xu gaoseng zhuan is a crucial text in the study of so-called Early Chan. Though it is often thought that Daoxuan was attempting to promote the Bodhidharma lineage, recent studies have suggested that he was actually attacking Bodhidharma and his later followers. The present article suggests that such readings are incor rect and that Daoxuan was in fact attacking the followers of the Three Levels (Sanjie) movement founded by Xinxing, whose role in defining the meaning of chan during the seventh century has not been sufficiently appreciated. Résumé Étant un des premiers documents à parler de Bodhidharma, le Xu Gaoseng zhuan de Daoxuan constitue une source cruciale pour l’étude du “Chan primitif”. Même si l’on considère le plus souvent que Daoxuan s’efforçait de promouvoir la lignée de Bodhidharma, plusieurs études récentes suggèrent qu’en fait il attaquait Bodhidharma et ses héritiers. L’auteur suggère que cette interprétation n’est pas correcte: en réalité Daoxuan s’attaquait aux adhérents du mouvement des “Trois niveaux” (Sanjie) fondé par Xinxing, dont la contribution à la définition du sens duchan pendant le viie siècle n’a pas encore été suffisamment appréciée. Keywords Buddhism, Chan, Daoxuan, Xinxing, Sanjie movement © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2008 DOI: 10.1163/008254308X367022 50 E. Greene / T’oung Pao 94 (2008) 49-114 In the words of Bernard Faure, “Although Bodhidharma’s biography is obscure, his life is relatively well known.”1 Indeed, early records of this monk are so vague, and later hagiography embellishes him so extravagantly, that the best approach seems to be, as Faure ultimately suggests, that we treat Bodhidharma not as an individual but as a textual paradigm. -

Buddhist Adoption in Asia, Mahayana Buddhism First Entered China

Buddhist adoption in Asia, Mahayana Buddhism first entered China through Silk Road. Blue-eyed Central Asian monk teaching East-Asian monk. A fresco from the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves, dated to the 9th century; although Albert von Le Coq (1913) assumed the blue-eyed, red-haired monk was a Tocharian,[1] modern scholarship has identified similar Caucasian figures of the same cave temple (No. 9) as ethnic Sogdians,[2] an Eastern Iranian people who inhabited Turfan as an ethnic minority community during the phases of Tang Chinese (7th- 8th century) and Uyghur rule (9th-13th century).[3] Buddhism entered Han China via the Silk Road, beginning in the 1st or 2nd century CE.[4][5] The first documented translation efforts by Buddhist monks in China (all foreigners) were in the 2nd century CE under the influence of the expansion of the Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory of the Tarim Basin under Kanishka.[6][7] These contacts brought Gandharan Buddhist culture into territories adjacent to China proper. Direct contact between Central Asian and Chinese Buddhism continued throughout the 3rd to 7th century, well into the Tang period. From the 4th century onward, with Faxian's pilgrimage to India (395–414), and later Xuanzang (629–644), Chinese pilgrims started to travel by themselves to northern India, their source of Buddhism, in order to get improved access to original scriptures. Much of the land route connecting northern India (mainly Gandhara) with China at that time was ruled by the Kushan Empire, and later the Hephthalite Empire. The Indian form of Buddhist tantra (Vajrayana) reached China in the 7th century.