Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erie Canalway Map & Guide

National Park Service Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor U.S. Department of the Interior Erie Canalway Map & Guide Pittsford, Frank Forte Pittsford, The New York State Canal System—which includes the Erie, Champlain, Cayuga-Seneca, and Oswego Canals—is the centerpiece of the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor. Experience the enduring legacy of this National Historic Landmark by boat, bike, car, or on foot. Discover New York’s Dubbed the “Mother of Cities” the canal fueled the growth of industries, opened the nation to settlement, and made New York the Empire State. (Clinton Square, Syracuse, 1905, courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Extraordinary Canals Company Collection.) pened in 1825, New York’s canals are a waterway link from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes through the heart of upstate New York. Through wars and peacetime, prosperity and This guide presents exciting Orecession, flood and drought, this exceptional waterway has provided a living connection things to do, places to go, to a proud past and a vibrant future. Built with leadership, ingenuity, determination, and hard work, and exceptional activities to the canals continue to remind us of the qualities that make our state and nation great. They offer us enjoy. Welcome! inspiration to weather storms and time-tested knowledge that we will prevail. Come to New York’s canals this year. Touch the building stones CONTENTS laid by immigrants and farmers 200 years ago. See century-old locks, lift Canals and COVID-19 bridges, and movable dams constructed during the canal’s 20th century Enjoy Boats and Boating Please refer to current guidelines and enlargement and still in use today. -

Barge Canal” Is No Longer an Accurate Description of the New York State Canals Marine Activity on New York’S Canals

The Story of the Afterword Today, the name “Barge Canal” is no longer an accurate description of the New York State Canals marine activity on New York’s canals. Trains and trucks have taken over the transport of most cargo that once moved on barges along the canals, but the canals remain a viable waterway for navigation. Now, pleasure boats, tour Historical and Commercial Information boats, cruise ships, canoes and kayaks comprise the majority of vessels that ply the waters of the legendary Erie and the Champlain, Oswego and Cayuga- Seneca canals, which now constitute the 524-mile New York State Canal ROY G. FINCH System. State Engineer and Surveyor While the barges now are few, this network of inland waterways is a popular tourism destination each year for thousands of pleasure boaters as well as visitors by land, who follow the historic trade route that made New York the “Empire State.” Across the canal corridor, dozens of historic sites, museums and community festivals in charming port towns and bustling cities invite visitors to step back in time and re-live the early canal days when “hoggees” guided mule-drawn packet boats along the narrow towpaths. Today, many of the towpaths have been transformed into Canalway Trail segments, extending over 220 miles for the enjoyment of outdoor enthusiasts from near and far who walk, bike and hike through scenic and historic canal areas. In 1992, legislation was enacted in New York State which changed the name of the Barge Canal to the “New York State Canal System” and transferred responsibility for operation and maintenance of the Canal System from the New York State Department of Transportation to the New York State Canal Corporation, a newly created subsidiary of the New York State Thruway Authority. -

Vision 2030 Comprehensive Plan

New York State's only Port on Lake Ontario VISION 2030 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN March 2021 Table of Contents Section Page Vision ..........................................................................................................................................................................................1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................................1 Historic Preservation and Educational Assets ...................................................................................................5 Existing Improvements and Conditions .........................................................................................................5 The Plan to Advance the Vision for Historic and Educational Assets ............................................5 Commercial Development and Economic Development Programs .................................................5 Existing Improvements and Conditions .........................................................................................................5 Plans to Advance the Vision with Port Projects ..........................................................................................8 Current Port Commodities ......................................................................................................................................10 Plans to Advance the Vision with Industrial Projects ..............................................................................10 -

Greater Syracuse Area Waterway Destinations and Services

Waterway Destinations and Services Map Central Square Y¹ `G Area Syracuse Greater 37 C Brewerton International a e m t ic Speedway Bradbury's R ou d R Boatel !/ y Remains of 5 Waterfront nt Bradbury Rd 1841 Lock !!¡ !l Fort Brewerton State Dock ou Caughdenoy Marina C !Z!x !5 Alb County Route 37 a Virginia St ert Palmer Ln bc !x !x !Z Weber Rd !´ zabeth St N River Dr !´ E R North St Eli !£ iver R C a !´ A bc d !º UG !x W Genesee St H Big Bay B D !£ E L ÆJ !´ \ N A ! 5 O C !l Marina !´ ! Y !5 K )§ !x !x !´ ÆJ Mercer x! Candy's Brewerton x! N B a Memorial 5 viga Ç7 Winter Harbor r Y b Landing le hC Boat Yard e ! Cha Park FA w nn e St NCH Charley's Boat Livery

National Significance and Historical Context

2.1 2 National Signifi cance and Historical Context NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE OVERVIEW Th e Erie Canal is the most successful and infl uential human-built waterway and one of the most important works of civil engineering and construction in North America. It facilitated and shaped the course of settlement of the North- east, Midwest, and Great Plains, knit together the Atlantic Seaboard with the area west of the Appalachian Mountains, solidifi ed New York City’s place as the young nation’s principal seaport and commercial center, and became a central element forging the national identity. New York’s canal system, including the Erie Canal and its laterals – principally the Champlain, Oswego, and Cayuga-Seneca Canals – opened the interior of the continent. Built through the only low-level gap between the Appalachian Mountain chain and the Adirondack Mountains, the Erie Canal provided one of the principal routes for migration and an economical and reliable means for transporting agricultural products and manufactured goods between the American interior, the eastern seaboard, and Europe. Th e Erie Canal was a heroic feat of early 19th century engineering and construc- tion, and at 363 miles long, more than twice the length of any canal in Europe. Photo: It was without precedent in North America, designed and built through sparsely Postcard image of canal basin in Clinton Square, Syracuse, ca. 1905 settled territory by surveyors, engineers, contractors, and laborers who had to learn much of their craft on the job. Engineers and builders who got their start on New York’s canals went on to construct other canals, railroads, and public water supplies throughout the new nation. -

NYSCS Recreational Pass Information

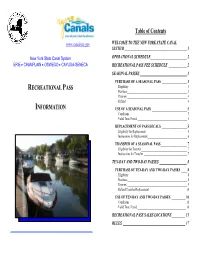

Table of Contents www.canals.ny.gov WELCOME TO THE NEW YORK STATE CANAL SYSTEM _________________________________________ 1 New York State Canal System OPERATIONAL SCHEDULE________________________ 2 ERIE CHAMPLAIN OSWEGO CAYUGA-SENECA RECREATIONAL PASS FEE SCHEDULE ____________ 2 SEASONAL PASSES _______________________________ 3 PURCHASE OF A SEASONAL PASS __________________ 3 RECREATIONAL PASS Eligibility______________________________________________ 3 Purchase_______________________________________________ 3 Payment _______________________________________________ 4 Refund ________________________________________________ 4 INFORMATION USE OF A SEASONAL PASS _________________________ 5 Conditions _____________________________________________ 5 Valid Time Period _______________________________________ 5 REPLACEMENT OF PASS DECALS __________________ 5 Eligibility for Replacement ________________________________ 5 Instructions for Replacement_______________________________ 6 TRANSFER OF A SEASONAL PASS___________________ 7 Eligibility for Transfer____________________________________ 7 Instructions for Transfer __________________________________ 7 TEN-DAY AND TWO-DAY PASSES __________________ 8 PURCHASE OF TEN-DAY AND TWO-DAY PASSES ____ 8 Eligibility______________________________________________ 8 Purchase_______________________________________________ 8 Payment _______________________________________________ 9 Refund/Transfer/Replacement_____________________________ 10 USE OF TEN-DAY AND TWO-DAY PASSES __________ 10 Conditions ____________________________________________ -

Wreck of the St. Peter (1874) – National Register of Historic Places

Proposal to the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration’s Marine Sanctuary Program 2017 Wreck of the St. Peter (1874) – National Register of Historic Places 0 Section I – Basics Nomination Title: The Great Lake Ontario National Marine Sanctuary Nominator Names(s) & Affiliations(s): Andrew Cuomo, Governor of New York; Kevin Gardner, Chairman of the Oswego County Legislature; Scott Gray, Chairman of the Jefferson County Legislature; Keith Batman, Chairman of the Cayuga County Legislature; Steve LeRoy, Chairman of the Wayne County Board of Supervisors; and William Barlow, Mayor of the City of Oswego. Point of Contact: Philip Church, Oswego County Administrator, Chairman of Great Lake Ontario National Marine Sanctuary Nomination Task Force; 46 East Bridge Street, Oswego 13126; phone 315-349-8235, fax 315-349-8237, e-mail [email protected] Section II – Introduction Narrative Description: The proposed Great Lake Ontario National Marine Sanctuary includes unique and significant submerged cultural resources within a corridor that is one of the most historically significant regions in the Great Lakes and the North American continent. Located in the southeastern and eastern quadrant of Lake Ontario, this area and its tributaries provided food and transportation trade routes for indigenous peoples and early European explorers, such as Samuel de Champlain. During the colonial period, it was a strategic theater of conflict among European powers and the young American republic. Military actions involving naval and land forces occurred at Sodus, Oswego, Big Sandy Creek, and Sackets Harbor during the French and Indian War, Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. These actions involved historic figures such as the Marquis de Montcalm, Sir William Johnson, Commodore Isaac Chauncey and Sir James Yeo. -

Oswego Canal Corridor BOA

Oswego Canal Corridor BOA Appendix M: PHASE IA AND pHASE IB NOVEMBER 2019 PHASE IA LITERATURE REVIEW AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SENSITIVITY ASSESSMENT & PHASE IB ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIELD INVESTIGATION City of Oswego Waterfront Development Plan 1, 29 & 41 Lake Street City of Oswego Oswego County, New York Prepared by: NANCY M. CLARK, MA & L. JASON FENTON HUDSON MOHAWK ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONSULTANTS, LLC 153 SECOND AVENUE TROY, NEW YORK 12180 CELL PHONE: (518) 237-5637, (518) 569-0203 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.HMarchaeology.com Submitted to: BERGMANN ASSOCIATES, PC 280 EAST BROAD STREET ROCHESTER, NEW YORK Prepared for: CITY OF OSWEGO OSWEGO COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT, TOURISM & PLANNING 46 E. BRIDGE STREET OSWEGO, NY 13126 AUGUST 2018 Phase IA Literature Review and Archaeological Sensitivity Assessment – City of Oswego Waterfront Development Plan, 1, 29 and 41 Lake Street, City of Oswego, Oswego County, New York City of Oswego Waterfront Development Plan Project Phase IA Literature Review and Archaeological Sensitivity Assessment & Phase IB Archaeological Field Investigation SHPO Review Number: State/Federal Agencies: Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) for USACOE compliance and SEQRA guidelines under Section 14.09 of New York State Historic Preservation Act (SHPA) for permitting by NYS Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) LOCATION Municipalities: City of Oswego County: Oswego County MCDs: 07540 SURVEY AREA: Length: Width: Number of Acres Surveyed: Project area and Area of Potential Effect (APE) are 13.98 acres USGS 7.5 Minute Quad Map: 1954 USGS Oswego West, photorevised 1978 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OVERVIEW AND RESULTS Number & Interval of Shovel Tests: 0 Number and name of prehistoric sites identified: 0 Number and name of historic sites identified: 0 Number and name of sites recommended for Phase II/Avoidance: 0 RESULTS OF ARCHITECTURAL SURVEY Number of buildings/structures/cemeteries within project area: Several Number of buildings/structures/cemeteries adjacent to project area: Several. -

2021 Map and Guide

National Park Service Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor U.S. Department of the Interior Erie Canalway Map & Guide Scotia, Frank Forte Enjoy the Great Outdoors Call of the Loon Albany, Along New York’s Canals ead to the water to find adventure and fun along more than 500 miles of canals and connected waterways and trails. This is the perfect year to look to the canals for memorable CONTENTS and safe day trips and vacation getaways. From boat rentals to multiday bike rides to H Get on the Water . .2-3 visiting state and national parks, there’s plenty to explore on and off the water. Erie Canalway Map . 4-5 The Empire State Trail . 6 Get on the Water Hit the Trail Discover Canal Communities Cycling with Kids . 7 The New York State Canal System— The Canalway Trail is an ideal place for One of the best parts of visiting the Erie Canalway Challenge . 7 which includes the Erie, Champlain, fitness and fun. Spend a few hours walking Canalway National Heritage Corridor is Cayuga-Seneca, and Oswego Canals— or cycling and seeing the sites or plan a exploring the many cities, towns, and A National Treasure . 8 is the centerpiece of the Erie Canalway longer cycling trip to really experience villages along the waterway. Many of National Heritage Corridor. Relax and all the trail has to offer. The 360 mile these communities provide visitor centers enjoy a canal boat tour or multiday east-west trail from Buffalo to Albany with restrooms, showers, and other services Canals and COVID-19 voyage. -

Oswego Harbor NOAA Chart 14813

BookletChart™ Oswego Harbor NOAA Chart 14813 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Included Area Published by the Prominent features.–The strobe-lighted stacks at the powerplant 1 mile W of the river mouth are prominent in the harbor approach. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Channels.–A dredged approach channel leads E from the lake S of a National Ocean Service detached breakwater and between converging breakwaters into the Office of Coast Survey outer harbor of refuge. From the outer harbor, the inner harbor extends up the Oswego River for 0.5 mile along the Oswego piers. Another www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov channel, protected by an extension of the W breakwater, extends SW 888-990-NOAA from the outer harbor along the shore to a turning basin. The breakwaters are marked by lights, and the channels by lighted and What are Nautical Charts? unlighted buoys. A fog signal is at the light on the west breakwater. In April 2004, the controlling depths were 23.3 feet in the approach and Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show in the channel through the outer harbor to the mouth of the river, water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much thence 20.0 feet in the river channel to the head of the federal project more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and at Seneca Street. The outer harbor W of the entrance channel had efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial depths of 11 to 16 feet (except for lesser depths in an area near the S ships that carry America’s commerce. -

Oswego Canal

OSWEGO CANAL The Oswego Canal connects the Erie Canal at Three Rivers to Oswego Harbor at Lake Ontario. Though the Oswego Canal is fairly short, only 23 miles, it drops 188 feet and has long provided a critical connection to Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River. The Oswego River’s bays and back channels are well suited for boating, fishing, birdwatching, canoeing, and kayaking. Visitors from around the world are drawn to Oswego’s active port, renowned for its festivals and exceptional sport fishing. The Oswego Canal originally started at its confluence with the Erie Canal in downtown Syracuse, across from the weigh lock building, now home to the Erie Canal Museum. From there it ran along the east shore of Onondaga Lake. From Phoenix down to the Lake Ontario, the canal used a succession of constructed channels with locks and river segments with towing paths along the east side of the Oswego River. Remnants of these 19th-century structures are common along the modern canal and are easily explored by paddlers. FOR MORE INFORMATION: More information about things to do in the Oswego Canal area is available from visitoswegocounty.com. eriecanalway.org | NEW YORK STATE CANALWAY WATER TRAIL GUIDEBOOK 223 Oswego Canal–Three Rivers Mishemokwa—Great Bear Springs Recreation Area 54 F >= i 481 6 s ml >= h >=57 S i 264 x ml m Old Oswego Canal Guard Lock i l e C O Mile 6.39 r e e k >=46 Old Oswego Canal Lock 6 O Mile 5.40 VOLNEY C ST O r S e W e k PE EG 57 ND O >= ER GA ST Lock O1, Phoenix O Mile 2.15 ST CK 12 189 O >= >= Lock Island Park L R D O -

Lucian Minor, Cosmopolitan Virginia Gentleman of the Old School

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1948 Lucian Minor, Cosmopolitan Virginia Gentleman of the Old School James Norman McKean College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McKean, James Norman, "Lucian Minor, Cosmopolitan Virginia Gentleman of the Old School" (1948). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624474. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-a5m5-sw85 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Caai«a Mta«ri mm/un a«lB*lt%«<s t* P artial m flilM irtt WWy■■ Akibi^;Wrni^m- ' ■ 'JW^^pB»'4PWI^F'tt Vfr^fc1.. aL’1 <*■ TUa Oallag* ' of VflUui aat Kary for tha aagraa «f K*atar af Aria Luolan Minor I Cosmopolitan Virginia Gentleman of the Old School Table of Contents I Prefatory 1 II The Minor Family in Virginia 9 III Fro® Birth to Manhood 15 IV The Early Thirties 50 V The Southern Literary Messenger 59 VI Journeys to the Vest 88 A ppendix MS Introduction to A Peep at Mew England A -l MS A Journey to the Vest in 1836 A -7 Bibliography V it a 1 I Prefatory Lucian Minor, a Virginia gentleman, changed a s c o m p le te ly during the decade of the eighteen-thirties as did th e n a tio n o f w hich he was a citizen* For over forty years the United S t a t e s had functioned as a fairly harmonious u n i t .