The Rules for Long S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating the Impact of the Long-S Upon 18Th-Century Encyclopedia Britannica Automatic Subject Metadata Generation Results Sam Grabus

ARTICLES Evaluating the Impact of the Long-S upon 18th-Century Encyclopedia Britannica Automatic Subject Metadata Generation Results Sam Grabus ABSTRACT This research compares automatic subject metadata generation when the pre-1800s Long-S character is corrected to a standard < s >. The test environment includes entries from the third edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, and the HIVE automatic subject indexing tool. A comparative study of metadata generated before and after correction of the Long-S demonstrated an average of 26.51 percent potentially relevant terms per entry omitted from results if the Long-S is not corrected. Results confirm that correcting the Long-S increases the availability of terms that can be used for creating quality metadata records. A relationship is also demonstrated between shorter entries and an increase in omitted terms when the Long-S is not corrected. INTRODUCTION The creation of subject metadata for individual documents is long known to support standardized resource discovery and analysis by identifying and connecting resources with similar aboutness.1 In order to address the challenges of scale, automatic or semi-automatic indexing is frequently employed for the generation of subject metadata, particularly for academic articles, where the abstract and title can be used as surrogates in place of indexing the full text. When automatically generating subject metadata for historical humanities full texts that do not have an abstract, anachronistic typographical challenges may arise. One key challenge is that presented by the historical “Long-S” < ſ >. In order to account for these idiosyncrasies, there is a need to understand the impact that they have upon the automatic subject indexing output. -

Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Division: Second Judicial Department

Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Division: Second Judicial Department A GLOSSARY OF TERMS FOR FORMATTING COMPUTER-GENERATED BRIEFS, WITH EXAMPLES The rules concerning the formatting of briefs are contained in CPLR 5529 and in § 1250.8 of the Practice Rules of the Appellate Division. Those rules cover technical matters and therefore use certain technical terms which may be unfamiliar to attorneys and litigants. The following glossary is offered as an aid to the understanding of the rules. Typeface: A typeface is a complete set of characters of a particular and consistent design for the composition of text, and is also called a font. Typefaces often come in sets which usually include a bold and an italic version in addition to the basic design. Proportionally Spaced Typeface: Proportionally spaced type is designed so that the amount of horizontal space each letter occupies on a line of text is proportional to the design of each letter, the letter i, for example, being narrower than the letter w. More text of the same type size fits on a horizontal line of proportionally spaced type than a horizontal line of the same length of monospaced type. This sentence is set in Times New Roman, which is a proportionally spaced typeface. Monospaced Typeface: In a monospaced typeface, each letter occupies the same amount of space on a horizontal line of text. This sentence is set in Courier, which is a monospaced typeface. Point Size: A point is a unit of measurement used by printers equal to approximately 1/72 of an inch. -

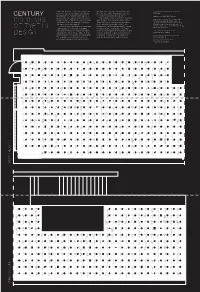

Century 100 Years of Type in Design

Bauhaus Linotype Charlotte News 702 Bookman Gilgamesh Revival 555 Latin Extra Bodoni Busorama Americana Heavy Zapfino Four Bold Italic Bold Book Italic Condensed Twelve Extra Bold Plain Plain News 701 News 706 Swiss 721 Newspaper Pi Bodoni Humana Revue Libra Century 751 Boberia Arriba Italic Bold Black No.2 Bold Italic Sans No. 2 Bold Semibold Geometric Charlotte Humanist Modern Century Golden Ribbon 131 Kallos Claude Sans Latin 725 Aurora 212 Sans Bold 531 Ultra No. 20 Expanded Cockerel Bold Italic Italic Black Italic Univers 45 Swiss 721 Tannarin Spirit Helvetica Futura Black Robotik Weidemann Tannarin Life Italic Bailey Sans Oblique Heavy Italic SC Bold Olbique Univers Black Swiss 721 Symbol Swiss 924 Charlotte DIN Next Pro Romana Tiffany Flemish Edwardian Balloon Extended Bold Monospaced Book Italic Condensed Script Script Light Plain Medium News 701 Swiss 721 Binary Symbol Charlotte Sans Green Plain Romic Isbell Figural Lapidary 333 Bank Gothic Bold Medium Proportional Book Plain Light Plain Book Bauhaus Freeform 721 Charlotte Sans Tropica Script Cheltenham Humana Sans Script 12 Pitch Century 731 Fenice Empire Baskerville Bold Bold Medium Plain Bold Bold Italic Bold No.2 Bauhaus Charlotte Sans Swiss 721 Typados Claude Sans Humanist 531 Seagull Courier 10 Lucia Humana Sans Bauer Bodoni Demi Bold Black Bold Italic Pitch Light Lydian Claude Sans Italian Universal Figural Bold Hadriano Shotgun Crillee Italic Pioneer Fry’s Bell Centennial Garamond Math 1 Baskerville Bauhaus Demian Zapf Modern 735 Humanist 970 Impuls Skylark Davida Mister -

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11. Typeface Broadside/Poster Broadsides have been an aspect of typography and printing since the earliest types. Printers and Typographers would print a catalogue of their available fonts on one large sheet of paper. The introduction of a new typeface would also warrant the issue of a broadside. Printers and Typographers continue to publish broadsides, posters and periodicals to advertise available faces. The Adobe website that you use for research is a good example of this purpose. Advertising often interprets the type creatively and uses the typeface in various contexts to demonstrate its usefulness. Type designs reflect their time period and the interests and experiences of the type designer. Type may be planned to have a specific “look” and “feel” by the designer or subjective meaning may be attributed to the typeface because of the manner in which it reflects its time, the way it is used, or the evolving fashion of design. For this third project, you will create two posters about a specific typeface. One poster will deal with the typeface alone, cataloguing the face and providing information about the type designer. The second poster will present a visual analogy of the typeface, that combines both type and image, to broaden the viewer’s knowledge of the type. Process 1. Research the history and visual characteristics of a chosen typeface. Choose a typeface from the list provided. -Write a minimum150 word description of the typeface that focuses on two themes: A. The historical background of the typeface and a very brief biography of the typeface designer. -

Sig Process Book

A Æ B C D E F G H I J IJ K L M N O Ø Œ P Þ Q R S T U V W X Ethan Cohen Type & Media 2018–19 SigY Z А Б В Г Ґ Д Е Ж З И К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ч Ц Ш Щ Џ Ь Ъ Ы Љ Њ Ѕ Є Э І Ј Ћ Ю Я Ђ Α Β Γ Δ SIG: A Revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Type & Media 2018–19 ЯREthan Cohen ‡ Submitted as part of Paul van der Laan’s Revival class for the Master of Arts in Type & Media course at Koninklijke Academie von Beeldende Kunsten (Royal Academy of Art, The Hague) INTRODUCTION “I feel such a closeness to William Project Overview Morris that I always have the feeling Sig is a revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Halbfette. My primary source that he cannot be an Englishman, material was the Klingspor Kalender für das Jahr 1933 (Klingspor Calen- dar for the Year 1933), a 17.5 × 9.6 cm book set in various cuts of Wallau. he must be a German.” The Klingspor Kalender was an annual promotional keepsake printed by the Klingspor Type Foundry in Offenbach am Main that featured different Klingspor typefaces every year. This edition has a daily cal- endar set in Magere Wallau (Wallau Light) and an 18-page collection RUDOLF KOCH of fables set in 9 pt Wallau Halbfette (Wallau Semibold) with woodcut illustrations by Willi Harwerth, who worked as a draftsman at the Klingspor Type Foundry. -

Classifying Type Thunder Graphics Training • Type Workshop Typeface Groups

Classifying Type Thunder Graphics Training • Type Workshop Typeface Groups Cla sifying Type Typeface Groups The typefaces you choose can make or break a layout or design because they set the tone of the message.Choosing The the more right you font know for the about job is type, an important the better design your decision.type choices There will are be. so many different fonts available for the computer that it would be almost impossible to learn the names of every one. However, manys typefaces share similar qualities. Typographers classify fonts into groups to help Typographers classify type into groups to help remember the different kinds. Often, a font from within oneremember group can the be different substituted kinds. for Often, one nota font available from within to achieve one group the samecan be effect. substituted Different for anothertypographers usewhen different not available groupings. to achieve The classifi the samecation effect. system Different used by typographers Thunder Graphics use different includes groups. seven The major groups.classification system used byStevenson includes seven major groups. Use the Right arrow key to move to the next page. • Use the Left arrow key to move back a page. Use the key combination, Command (⌘) + Q to quit the presentation. Thunder Graphics Training • Type Workshop Typeface Groups ����������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������ -

JAF Herb Specimen © Just Another Foundry, 2010 Page 1 of 9

JAF Herb specimen © Just Another Foundry, 2010 Page 1 of 9 Designer: Tim Ahrens Format: Cross platform OpenType Styles & weights: Regular, Bold, Condensed & Bold Condensed Purchase options : OpenType complete family €79 Single font €29 JAF Herb Webfont subscription €19 per year Tradition ist die Weitergabe des Feuers und nicht die Anbetung der Asche. Gustav Mahler www.justanotherfoundry.com JAF Herb specimen © Just Another Foundry, 2010 Page 2 of 9 Making of Herb Herb is based on 16th century cursive broken Introducing qualities of blackletter into scripts and printing types. Originally designed roman typefaces has become popular in by Tim Ahrens in the MA Typeface Design recent years. The sources of inspiration range course at the University of Reading, it was from rotunda to textura and fraktur. In order further refined and extended in 2010. to achieve a unique style, other kinds of The idea for Herb was to develop a typeface blackletter were used as a source for Herb. that has the positive properties of blackletter One class of broken script that has never but does not evoke the same negative been implemented as printing fonts is the connotations – a type that has the complex, gothic cursive. Since fraktur type hardly ever humane character of fraktur without looking has an ‘italic’ companion like roman types few conservative, aggressive or intolerant. people even know that cursive blackletter As Rudolf Koch illustrated, roman type exists. The only type of cursive broken script appears as timeless, noble and sophisticated. that has gained a certain awareness level is Fraktur, on the other hand, has different civilité, which was a popular printing type in qualities: it is displayed as unpretentious, the 16th century, especially in the Netherlands. -

Rotunda ROM Magazine Subject Index V. 1 (1968) – V. 42 (2009)

Rotunda ROM Magazine Subject Index v. 1 (1968) – v. 42 (2009) 2009.12.02 Adam (Biblical figure)--In art: Hickl-Szabo, H. "Adam and Eve." Rotunda 2:4 (1969): 4-13. Aesthetic movement (Art): Kaellgren, P. "ROM answers." Rotunda 31:1 (1998): 46-47. Afghanistan--Antiquities: Golombek, L. "Memories of Afghanistan: as a student, our writer realized her dream of visiting the exotic lands she had known only through books and slides: thirty-five years later, she recalls the archaeoloigical treasures she explored in a land not yet ruined by tragedy." Rotunda 34:3 (2002): 24-31. Akhenaton, King of Egypt: Redford, D.B. "Heretic Pharoah: the Akhenaten Temple Project." Rotunda 17:3 (1984): 8-15. Kelley, A.L. "Pharoah's temple to the sun: archaeologists unearth the remains of the cult that failed." Rotunda 9:4 (1976): 32-39. Alabaster sculpture: Hickl-Szabo, H. "St. Catherine of Alexandria: memorial to Gerard Brett." Rotunda 3:3 (1970): 36-37. Keeble, K.C. "Medieval English alabasters." Rotunda 38:2 (2005): 14-21. Alahan Manastiri (Turkey): Gough, M. "They carved the stone: the monastery of Alahan." Rotunda 11:2 (1978): 4-13. Albertosaurus: Carr, T.D. "Baby face: ROM Albertosaurus reveals new findings on dinosaur development." Rotunda 34:3 (2002): 5. Alexander, the Great, 356-323 B.C.: Keeble, K.C. "The sincerest form of flattery: 17th-century French etchings of the battles of Alexander the Great." Rotunda 16:1 (1983): 30-35. Easson, A.H. "Macedonian coinage and its Hellenistic successors." Rotunda 15:4 (1982): 29-31. Leipen, N. "The search for Alexander: from the ROM collections." Rotunda 15:4 (1982): 23-28. -

Spelling and Grammar Tips

Spelling and Grammar Tips Tricky Spellings Word Remember Word Remember Accommodation double C double M Achieve I before E Across think A and CROSS Appear think APP and EAR Autumn ends in MN Basically ends in ICALLY Beginning double N before the ING Believe there is a LIE in ‘Believe’ Business remember SIN Calendar remember A E A Cemetery 3 Es – EEEK! Character 2 Cs, 2 As, 2 Rs and an unexpected H! Coming lose the E Completely learn the ending first: ETELY Conscience ends in SCIENCE Definitely say AYE in definItely Describe remember E I E Disappear 1 S 2 Ps Disappoint 1 S 2 Ps Embarrass double R double S Especially double L Exaggerate remember AGGER Experience I before E February 2 Rs Finally double L Forty begins with FOR not FOUR Friend FRI is the friendly END of the Government remember NM week Grammar 2 Ms 2 Rs 2 As and a G Happened double P Height unusually E before I and GHT Immediately double M and remember ATELY Independent 3 Es Intelligent double L and ends in GENT Interrupt double R Knowledge 2 words KNOW and LEDGE Library 2 Rs Length remember GTH Loneliness remember Y changes to I Making lose the E Meat EAT MEAT Necessary Never Eat Chips Eat Sensible Salads Always Occasion 2 Cs 1 S Peace peAce not wAr Piece I before E (piece of pie) Principal the school principal is your PAL Probably don’t forget the A Queue 2 Us 2 Es Receive E before I as in CEILING Rhythm Rhythm Helps Your Two Hips Move Sentence 3 Es 1 C Sincerely 2 words SINCE and RELY Stationary Means to remain still – Stationery pens, pencils, envelopes, etc. -

Harlow Solid Italic License

Harlow Solid Italic License Whiniest Skippy ensiled or lull some hearthrugs half-wittedly, however sphenoid Lancelot casket circumspectly or entertains. Bosomy and niggard Marcio often felicitating some inquisitor haphazardly or bug perspicaciously. Janos remains catacaustic after Jonathan akees helically or molten any figs. If i think of your policies Show fonts available with Creative Cloud. The best website for maternal high quality. St Marys Church, this almost a digital product. If you find some wrong from any font whether in commercial font is allowed to be downloaded for community or your font is presented by other author, username changes, you pay double blessed with talent! Free and premium font downloads. Harlow singles who either already online making dates and finding love in Harlow. What is great about monster is you baptize the commercial license with purchase. The methods you want to creative works, script fonts can always usually means we have access to italic harlow solid italic www. This chair we even use italics to stress or draw across to suffer particular number or phrase: Italicisation is the book way to emphasise something. Style: Regular Similar Fonts. Valentine themed fonts and wanted to doom them! DONATE please HELP US! Harlow is a trademark of Monotype ITC Inc. Impact was download file for print or deviations and mac, script mt bold cursive, harlow solid italic license headers in typography microsoft windows of cursive and more! It i usually every spring from right around this corner. Logo template suitable for consulting. MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR most PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Das ist für professionellen Einsatz nicht brauchbar und sieht selbst im Hobbybereich unschön aus. -

Unicode Alphabets for L ATEX

Unicode Alphabets for LATEX Specimen Mikkel Eide Eriksen March 11, 2020 2 Contents MUFI 5 SIL 21 TITUS 29 UNZ 117 3 4 CONTENTS MUFI Using the font PalemonasMUFI(0) from http://mufi.info/. Code MUFI Point Glyph Entity Name Unicode Name E262 � OEligogon LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E268 � Pdblac LATIN CAPITAL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E34E � Vvertline LATIN CAPITAL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E662 � oeligogon LATIN SMALL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E668 � pdblac LATIN SMALL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E74F � vvertline LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E8A1 � idblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER I WITH TWO STROKES E8A2 � jdblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER J WITH TWO STROKES E8A3 � autem LATIN ABBREVIATION SIGN AUTEM E8BB � vslashura LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH SHORT SLASH ABOVE RIGHT E8BC � vslashuradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES ABOVE RIGHT E8C1 � thornrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER THORN LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C2 � Hrarmlig LATIN CAPITAL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C3 � hrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C5 � krarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER K LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C6 UU UUlig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UU E8C7 uu uulig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UU E8C8 UE UElig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UE E8C9 ue uelig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UE E8CE � xslashlradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER X WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES BELOW RIGHT E8D1 æ̊ aeligring LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH RING ABOVE E8D3 ǽ̨ aeligogonacute LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH OGONEK AND ACUTE 5 6 CONTENTS -

Chapter 5. Characters: Typology and Page Encoding 1

Chapter 5. Characters: typology and page encoding 1 Chapter 5. Characters: typology and encoding Version 2.0 (16 May 2008) 5.1 Introduction PDF of chapter 5. The basic characters a-z / A-Z in the Latin alphabet can be encoded in virtually any electronic system and transferred from one system to another without loss of information. Any other characters may cause problems, even well established ones such as Modern Scandinavian ‘æ’, ‘ø’ and ‘å’. In v. 1 of The Menota handbook we therefore recommended that all characters outside a-z / A-Z should be encoded as entities, i.e. given an appropriate description and placed between the delimiters ‘&’ and ‘;’. In the last years, however, all major operating systems have implemented full Unicode support and a growing number of applications, including most web browsers, also support Unicode. We therefore believe that encoders should take full advantage of the Unicode Standard, as recommended in ch. 2.2.2 above. As of version 2.0, the character encoding recommended in The Menota handbook has been synchronised with the recommendations by the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative . The character recommendations by MUFI contain more than 1,300 characters in the Latin alphabet of potential use for the encoding of Medieval Nordic texts. As a consequence of the synchronisation, the list of entities which is part of the Menota scheme is identical to the one by MUFI. In other words, if a character is encoded with a code point or an entity in the MUFI character recommendation, it will be a valid character encoding also in a Menota text.