Whenever There Is a Line Or Tilde Over a Vowel, It Is an Abbreviation for the Letters M Or N. in This Case, the Full Word Is Quadam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating the Impact of the Long-S Upon 18Th-Century Encyclopedia Britannica Automatic Subject Metadata Generation Results Sam Grabus

ARTICLES Evaluating the Impact of the Long-S upon 18th-Century Encyclopedia Britannica Automatic Subject Metadata Generation Results Sam Grabus ABSTRACT This research compares automatic subject metadata generation when the pre-1800s Long-S character is corrected to a standard < s >. The test environment includes entries from the third edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, and the HIVE automatic subject indexing tool. A comparative study of metadata generated before and after correction of the Long-S demonstrated an average of 26.51 percent potentially relevant terms per entry omitted from results if the Long-S is not corrected. Results confirm that correcting the Long-S increases the availability of terms that can be used for creating quality metadata records. A relationship is also demonstrated between shorter entries and an increase in omitted terms when the Long-S is not corrected. INTRODUCTION The creation of subject metadata for individual documents is long known to support standardized resource discovery and analysis by identifying and connecting resources with similar aboutness.1 In order to address the challenges of scale, automatic or semi-automatic indexing is frequently employed for the generation of subject metadata, particularly for academic articles, where the abstract and title can be used as surrogates in place of indexing the full text. When automatically generating subject metadata for historical humanities full texts that do not have an abstract, anachronistic typographical challenges may arise. One key challenge is that presented by the historical “Long-S” < ſ >. In order to account for these idiosyncrasies, there is a need to understand the impact that they have upon the automatic subject indexing output. -

ISO Basic Latin Alphabet

ISO basic Latin alphabet The ISO basic Latin alphabet is a Latin-script alphabet and consists of two sets of 26 letters, codified in[1] various national and international standards and used widely in international communication. The two sets contain the following 26 letters each:[1][2] ISO basic Latin alphabet Uppercase Latin A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z alphabet Lowercase Latin a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z alphabet Contents History Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters Names for the two subsets Names for the letters Timeline for encoding standards Timeline for widely used computer codes supporting the alphabet Representation Usage Alphabets containing the same set of letters Column numbering See also References History By the 1960s it became apparent to thecomputer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin script in their (ISO/IEC 646) 7-bit character-encoding standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. The standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 8859 (8-bit character encoding) and ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin script with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.[1] Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters The Unicode block that contains the alphabet is called "C0 Controls and Basic Latin". -

Threshold Digraphs

Volume 119 (2014) http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/jres.119.007 Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology Threshold Digraphs Brian Cloteaux1, M. Drew LaMar2, Elizabeth Moseman1, and James Shook1 1National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 20899 2The College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA 23185 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] A digraph whose degree sequence has a unique vertex labeled realization is called threshold. In this paper we present several characterizations of threshold digraphs and their degree sequences, and show these characterizations to be equivalent. Using this result, we obtain a new, short proof of the Fulkerson-Chen theorem on degree sequences of general digraphs. Key words: digraph realizations; Fulkerson-Chen theorem; threshold digraphs. Accepted: May 6, 2014 Published: May 20, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/jres.119.007 1. Introduction Creating models of real-world networks, such as social and biological interactions, is a central task for understanding and measuring the behavior of these networks. A usual first step in this type of model creation is to construct a digraph with a given degree sequence. We examine the extreme case of digraph construction where for a given degree sequence there is exactly one digraph that can be created. What follows is a brief introduction to the notation used in the paper. For notation not otherwise defined, see Diestel [1]. We let G=( VE , ) be a digraph where E is a set of ordered pairs called arcs. If (,vw )∈ E, then we say w is an out-neighbor of v and v is an in-neighbor of w. -

![BBJ1RBR '(]~ F'o £.A2WB IJ.Boibiollb, •](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2472/bbj1rbr-fo-%C2%A3-a2wb-ij-boibiollb-442472.webp)

BBJ1RBR '(]~ F'o £.A2WB IJ.Boibiollb, •

801 80 mua1. , .. DDl&IOI o• OOLU•••• . I I:~ I BBJ1RBR '(]~ f'O £.A2WB IJ.BOIBIOllB, • •• • I r. • • Not Current- 1803 , 0 TIUI t ohn Tock r, q., of o ton, be i an k ep hi office at th eat of the o nbt practi , ither a an attorn y or a 0 &&all ontinue to b clerk of the ame. hat (until furth r orde ) it hall be om or cou ello to practi e in th· uch for thr e ea pa t in th uprem p cti ly b long, and that their pri ate r to be fair. &. t coun llors hall not pract• e a ........ ello , in h · court. 6. , That they hall re pecti el take the ------, do olemnly ear, that I ill or coun ellor of the court) uprightly, and upport the o titution of the nited &. t (unle and until it hall othe · e of · court hall be in the name of the That he cou ello and attorne , hall ake either an oath, or, in proper cribe b the rule of this court on that r•••, 1790, iz.: '' , , do olemnly be) that will demean m elf, as an attor .....· oo rt uprightl , an according to la , and that tion of he nited ta •'' hi f ju ice, in a er to the motion of the info him and the bar, that thi court of king' bench, and of chancery, in Eng ice of th• court; and that they will, tio therein circumstances may ren- x_...vu•• Not Current- 1803 0 '191, ebraary 4. -

Patterns Identification for Hitting Adjacent Key Errors Correction Using Neural Network Models

PATTERNS IDENTIFICATION FOR HITTING ADJACENT KEY ERRORS CORRECTION USING NEURAL NETWORK MODELS Jun Li Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge, 19 Silver Street, Cambridge, U.K. Karim Ouazzane, Sajid Afzal, Hassan Kazemian Faculty of Computing, London Metropolitan University, London, U.K. Keywords: QWERTY Keyboard, Probabilistic Neural Network, Backpropagation, Key Distance, Time Gap, Error Margin Distance. Abstract: People with Parkinson diseases or motor disability miss-stroke keys. It appears that keyboard layout, key distance, time gap are affecting this group of people’s typing performance. This paper studies these features based on neural network learning algorithms to identify the typing patterns, further to correct the typing mistakes. A specific user typing performance, i.e. Hitting Adjacent Key Errors, is simulated to pilot this research. In this paper, a Time Gap and a Prediction using Time Gap model based on BackPropagation Neural Network, and a Distance, Angle and Time Gap model based on the use of Probabilistic Neural Network are developed respectively for this particular behaviour. Results demonstrate a high performance of the designed model, about 70% of all tests score above Basic Correction Rate, and simulation also shows a very unstable trend of user’s ‘Hitting Adjacent Key Errors’ behaviour with this specific datasets. 1 INTRODUCTION technologies to tackle the typing errors as a whole, while there is no specific solution and convincing Computer users with disabilities or some elderly results for solving the ‘Miss-stroke’ error. people may have difficulties in accurately In the field of computer science, a neural manipulating the QWERTY keyboard. For example, network is a mathematical model or computational motor disability can cause significant typing model that is inspired by the structure and/or mistakes. -

The Dot Product

The Dot Product In this section, we will now concentrate on the vector operation called the dot product. The dot product of two vectors will produce a scalar instead of a vector as in the other operations that we examined in the previous section. The dot product is equal to the sum of the product of the horizontal components and the product of the vertical components. If v = a1 i + b1 j and w = a2 i + b2 j are vectors then their dot product is given by: v · w = a1 a2 + b1 b2 Properties of the Dot Product If u, v, and w are vectors and c is a scalar then: u · v = v · u u · (v + w) = u · v + u · w 0 · v = 0 v · v = || v || 2 (cu) · v = c(u · v) = u · (cv) Example 1: If v = 5i + 2j and w = 3i – 7j then find v · w. Solution: v · w = a1 a2 + b1 b2 v · w = (5)(3) + (2)(-7) v · w = 15 – 14 v · w = 1 Example 2: If u = –i + 3j, v = 7i – 4j and w = 2i + j then find (3u) · (v + w). Solution: Find 3u 3u = 3(–i + 3j) 3u = –3i + 9j Find v + w v + w = (7i – 4j) + (2i + j) v + w = (7 + 2) i + (–4 + 1) j v + w = 9i – 3j Example 2 (Continued): Find the dot product between (3u) and (v + w) (3u) · (v + w) = (–3i + 9j) · (9i – 3j) (3u) · (v + w) = (–3)(9) + (9)(-3) (3u) · (v + w) = –27 – 27 (3u) · (v + w) = –54 An alternate formula for the dot product is available by using the angle between the two vectors. -

The Selnolig Package: Selective Suppression of Typographic Ligatures*

The selnolig package: Selective suppression of typographic ligatures* Mico Loretan† 2015/10/26 Abstract The selnolig package suppresses typographic ligatures selectively, i.e., based on predefined search patterns. The search patterns focus on ligatures deemed inappropriate because they span morpheme boundaries. For example, the word shelfful, which is mentioned in the TEXbook as a word for which the ff ligature might be inappropriate, is automatically typeset as shelfful rather than as shelfful. For English and German language documents, the selnolig package provides extensive rules for the selective suppression of so-called “common” ligatures. These comprise the ff, fi, fl, ffi, and ffl ligatures as well as the ft and fft ligatures. Other f-ligatures, such as fb, fh, fj and fk, are suppressed globally, while making exceptions for names and words of non-English/German origin, such as Kafka and fjord. For English language documents, the package further provides ligature suppression rules for a number of so-called “discretionary” or “rare” ligatures, such as ct, st, and sp. The selnolig package requires use of the LuaLATEX format provided by a recent TEX distribution, e.g., TEXLive 2013 and MiKTEX 2.9. Contents 1 Introduction ........................................... 1 2 I’m in a hurry! How do I start using this package? . 3 2.1 How do I load the selnolig package? . 3 2.2 Any hints on how to get started with LuaLATEX?...................... 4 2.3 Anything else I need to do or know? . 5 3 The selnolig package’s approach to breaking up ligatures . 6 3.1 Free, derivational, and inflectional morphemes . -

The English Renaissance in Context: Looking at Older Books

The English Renaissance in Context: Looking at Older Books The History of the Book Books from the 16th and 17th centuries are both quite similar to and different from books today. The similarities include such things as use of the Codex format, general page layouts, use of title pages, etc. The codex book has been around for a long time. Its roots go back to the age of Cicero, though it only comes into more general use with the spread of Christianity throughout the later Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries CE. Since then, the codex book has undergone a long and gradual evolution during which time the book, its properties, and characteristics became firmly embedded in Western consciousness. Roughly speaking, the general layout of the page that we use today came into existence in the 13th century, with the rise of the universities and the creation of books for study. It is possible, for example, to look at a page in a medieval manuscript and experience a general orientation to it, even if you cannot actually read the text. The evolution of the book, we emphasize, was slow. Such conventions as pagination, title pages, foot or endnotes, tables of contents, indices, et alia are by and large relatively recent additions. We take these features for granted; but prior to the age of Gutenberg, they are hard to find. University of Pennsylvania Libraries - 1 - Furness Shakespeare Collection The English Renaissance in Context: Looking at Older Books Renaissance books can certainly look very different from books today. They exhibit a variety and diversity that have long since been standardized and homogenized. -

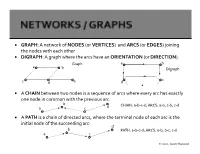

GRAPH: a Network of NODES (Or VERTICES) and ARCS (Or EDGES) Joining the Nodes with Each Other DIGRAPH: a Graph Where the Arcs Have an ORIENTATION (Or DIRECTION)

GRAPH: A network of NODES (or VERTICES) and ARCS (or EDGES) joining the nodes with each other DIGRAPH: A graph where the arcs have an ORIENTATION (or DIRECTION). Graph a b a b Digraph c c d e d A CHAIN between two nodes is a sequence of arcs where every arc has exactly one node in common with the previous arc b CHAIN: a-b-c-d; ARCS: a-b, c-b, c-d a c d A PATH is a chain of directed arcs, where the terminal node of each arc is the initial node of the succeeding arc: d b PATH: a-b-c-d; ARCS: a-b, b-c, c-d a c 2020, Jayant Rajgopal b d a c CYCLE: a-b-c-d; ARCS: a-b, c-b, c-d, d-a b d CIRCUIT: a-b-c-d; ARCS: a-b, b-c, c-d, d-a a c A graph is said to be CONNECTED if there is a continuous chain of edges joining any two vertices. A graph is STRONGLY CONNECTED if for all ordered pairs of vertices (i,j) there is a path of arcs from i to j. A graph is COMPLETE if every node is directly connected to every other node. c A TREE is a connected graph with no cycles. b d a A SPANNING TREE is a tree that contains all the nodes of a graph. b b e e a a c c Graph Spanning Tree d d 2020, Jayant Rajgopal GIVEN: A digraph G with a set of nodes 1,2,…,m, and a set of n directed arcs i-j emanating from node i and ending in node j, with each node i, a number bi that is the supply (if bi>0) or the demand (if bi<0); if bi=0, then the node is called a transshipment node, with each arc i-j, a flow of xij and a unit transportation / movement cost of cij. -

Approximations in Monte-Carlo Generators

Approximations in Monte-Carlo generators J. Bellm (Lund U.), Science Coffee, 25.1.2018 Colour Rearrangement for Dipole Showers Last friday: JB arXiv:1801.06113 J. Bellm (Lund U.), Science Coffee, 25.1.2018 Outline Walk though events generation What kind of approximations do we use? Can we improve the description? Recent developments from Lund J. Bellm (Lund U.), Science Coffee, 25.1.2018 What topic am I trying to cover? „…common words in the titles of the 2012 top 40 papers.“ symmetrymagazine.org J. Bellm (Lund U.), Science Coffee, 25.1.2018 What topic am I trying to cover? „…common words in the titles of the 2012 top 40 papers.“ symmetrymagazine.org J. Bellm (Lund U.), Science Coffee, 25.1.2018 What topic am I trying to cover? „…common words in the titles of the 2012 top 40 papers.“ symmetrymagazine.org J. Bellm (Lund U.), Science Coffee, 25.1.2018 How we simulate events? matrix elements event generators detector simulation analysis tools Rivet pdf J. Bellm (Lund U.), Science Coffee, 25.1.2018 How we simulate events? detector event generators matrix elements pdf picture: arXiv:1411.4085 J. Bellm (Lund U.), Science Coffee, 25.1.2018 Start simple Feynman gave a set of ‚simple‘ rules how to get cross sections from Lagrangians - extract rules from Lagrangian - draw diagrams and apply rules - average incoming possibilities - sum all final possibilities (once) J. Bellm (Lund U.), Science Coffee, 25.1.2018 Bit more complicated (fixed order) 100 50 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 -50 But: Divergences arise! UV —> Solved by renormalisation. -

Long Directed (S, T)-Path: FPT Algorithm

Long Directed (s; t)-Path: FPT Algorithm Fedor V. Fomin∗ Daniel Lokshtanovy Fahad Panolanz Saket Saurabhx Meirav Zehavi{ December 13, 2017 Abstract Given a digraph G, two vertices s; t 2 V (G) and a non-negative integer k, the Long Directed (s; t)-Path problem asks whether G has a path of length at least k from s to t. We present a simple algorithm that solves Long Directed (s; t)-Path in time O?(4:884k). This results also in an improvement upon the previous fastest algorithm for Long Directed Cycle. 1 Introduction Given a digraph (directed graph) G, two vertices s; t 2 V (G) and a non-negative integer k, the Long (Directed) (s; t)-Path problem asks whether G has an (s; t)-path (i.e. a path from s to t) of length at least k. Here, the term length refers to the number of vertices on the path, and paths are assumed to be directed simple paths. Observe that Long (s; t)-Path and k-(s; t)-Path are not equivalent problems, where that latter problem asks whether G has an (s; t)-path of length exactly k. Indeed, G may not have any (s; t)-path of length exactly k, or more generally, it may not even have any (s; t)-path of \short" length, but it may have an (s; t)-path of \long" length. For example, the only (s; t)-path of length at least k in G might be a Hamiltonian path. Both Long (s; t)-Path and k-(s; t)-Path are generalizations of the classic k-Path problem, whose objective is to determine whether G has a path of length at least k. -

Chapter 5. Characters: Typology and Page Encoding 1

Chapter 5. Characters: typology and page encoding 1 Chapter 5. Characters: typology and encoding Version 2.0 (16 May 2008) 5.1 Introduction PDF of chapter 5. The basic characters a-z / A-Z in the Latin alphabet can be encoded in virtually any electronic system and transferred from one system to another without loss of information. Any other characters may cause problems, even well established ones such as Modern Scandinavian ‘æ’, ‘ø’ and ‘å’. In v. 1 of The Menota handbook we therefore recommended that all characters outside a-z / A-Z should be encoded as entities, i.e. given an appropriate description and placed between the delimiters ‘&’ and ‘;’. In the last years, however, all major operating systems have implemented full Unicode support and a growing number of applications, including most web browsers, also support Unicode. We therefore believe that encoders should take full advantage of the Unicode Standard, as recommended in ch. 2.2.2 above. As of version 2.0, the character encoding recommended in The Menota handbook has been synchronised with the recommendations by the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative . The character recommendations by MUFI contain more than 1,300 characters in the Latin alphabet of potential use for the encoding of Medieval Nordic texts. As a consequence of the synchronisation, the list of entities which is part of the Menota scheme is identical to the one by MUFI. In other words, if a character is encoded with a code point or an entity in the MUFI character recommendation, it will be a valid character encoding also in a Menota text.