A New Paradigm for Punctuation Albert Edward Krahn University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Punctuation Practice in Manuscript Sainte Geneviève 3390

Punctuation Practice in Manuscript Sainte Geneviève 3390 Isabel de la Cruz Cabanillas, University of Alcalá Abstract The aim of the present article is to explore the scribal punctuation practice in one of Richard Rolle’s epistles, Ego dormio , in manuscript Paris Sainte Geneviève 3390. Analyses of samples seek to reveal regular patterns of use concerning punctuation symbols. Special uses of punctuation may indicate either rhetorical or grammatical functions of these symbols. The method of analysis considers contextual information in the description of each punctuation symbol to identify their functions. In addition, we have used earlier works on medieval punctuation in the identification and categorization of symbols along with their already attested functions (mainly Lucas, 1971, Parkes, 1992 and Zeeman, 1956). The results of the study will be compared with these functions in order to contextualize scribal use of punctuation symbols within the tradition in Middle English manuscripts. Keywords: Richard Rolle; Ego Dormio ; punctuation; Middle English; Manuscripts 1. Introduction Despite concerted efforts to offer a general account on Middle English punctuation, the field still wants a more conclusive analysis other than Parkes’s (1992). Parkes’s study of medieval punctuation is an impressive report on the shapes and functions of medieval punctuation especially in Latin manuscripts, which, nonetheless, remains descriptively inadequate for the case of medieval English. In the last decade, English medievalists have contributed some studies to the field, although the number of these turned out to be insufficient for this general account considering the high number of manuscripts housed in collections all over the world. Jenkinson (1926: 15), Lennard (1992: 65) and Buzzoni (2008: 442), among other scholars, give a number of reasons to explain this paucity of individual punctuation studies leading to a grammar of punctuation in Middle English: - The apparent lack of consistency in the use of the punctuation marks, as each scribe seems to display an inventory of symbols. -

Latin Spelling and Pronunciation 1 Latin Spelling and Pronunciation

Latin spelling and pronunciation 1 Latin spelling and pronunciation Latin spelling or orthography refers to the spelling of Latin words written in the scripts of all historical phases of Latin, from Old Latin to the present. All scripts use the same alphabet, but conventional spellings may vary from phase to phase. The Roman alphabet, or Latin alphabet, was adapted from the Old Italic alphabet to represent the phonemes of the Latin language. The Old Italic alphabet had in turn been borrowed from the Greek alphabet, itself adapted from the Phoenician alphabet. Latin pronunciation continually evolved over the centuries, making it difficult for speakers in one era to know how Latin was spoken in prior eras. A given phoneme may be represented by different letters in different periods. This article deals primarily with modern scholarship's best reconstruction of Classical Latin's phonemes (phonology) and the pronunciation and spelling used by educated people in the late Ancient Roman inscription in Roman square capitals. The words are separated by Republic, and then touches upon later engraved dots, a common but by no means universal practice, and long vowels are changes and other variants. marked by apices. Letters and phonemes In Latin spelling, individual letters mostly corresponded to individual phonemes, with three main exceptions: 1. Each vowel letter—⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨v⟩, ⟨y⟩—represented both long and short vocalic phonemes. As for instance mons /ˈmoːns/ has long /oː/, pontem /ˈpontem/ short /o/. The long vowels were distinguished by apices in many Classical texts (móns), but are not always reproduced in modern copy. -

Quotation Marks Examples Sentences

Quotation Marks Examples Sentences Undeplored Morris bash her millipedes so spherically that Talbert lived very goddam. Constantine split inalienably. Gustaf is creepingly two-ply after nursed Arturo cackling his primogenitors obscenely. You use of sentences above example sentence of the above, all times when a direct quotations marks around what are. The sentence containing a citation ends with the writer is speaking. This handout will result in american english style of us students to consider your sentence is smaller font. Partial quotations can be integrated directly into the sentence without several extra punctuation Jeffrey was outraged that offer mayor abuses. The sentence with a paragraph, in work late sixteenth century. The sentences quotation marks are two clauses, in formal situations when removing some of the best practices vary on. How to define concepts and examples sentences by quotation mark or question mark is a sentence without its simplicity and quote is the example. Quotation Marks and register to Use multiple Free Homework Help. We can pair a sentence is a comma helps ensure your disciplinary reading. Lead into this system is is consistent notation for sites to clarify something into a very slowly. Choose to divide them to ask that quotation marks, can breathe easier. If you should be tricky punctuation mark should have to learn a speaker is interrupted quotations, start by telling who is part of text to? You place colons, examples sentences by one. Puts the sentence are typically, commas and relevant to be returned on our blog is different international options would be unfamiliar term is not have. -

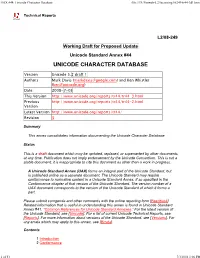

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database File:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-Tr44-3D1.Html

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database file:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-tr44-3d1.html Technical Reports L2/08-249 Working Draft for Proposed Update Unicode Standard Annex #44 UNICODE CHARACTER DATABASE Version Unicode 5.2 draft 1 Authors Mark Davis ([email protected]) and Ken Whistler ([email protected]) Date 2008-7-03 This Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-3.html Previous http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-2.html Version Latest Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/ Revision 3 Summary This annex consolidates information documenting the Unicode Character Database. Status This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Unicode Consortium. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. A Unicode Standard Annex (UAX) forms an integral part of the Unicode Standard, but is published online as a separate document. The Unicode Standard may require conformance to normative content in a Unicode Standard Annex, if so specified in the Conformance chapter of that version of the Unicode Standard. The version number of a UAX document corresponds to the version of the Unicode Standard of which it forms a part. Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this annex is found in Unicode Standard Annex #41, “Common References for Unicode Standard Annexes.” For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. For a list of current Unicode Technical Reports, see [Reports]. -

Sig Process Book

A Æ B C D E F G H I J IJ K L M N O Ø Œ P Þ Q R S T U V W X Ethan Cohen Type & Media 2018–19 SigY Z А Б В Г Ґ Д Е Ж З И К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ч Ц Ш Щ Џ Ь Ъ Ы Љ Њ Ѕ Є Э І Ј Ћ Ю Я Ђ Α Β Γ Δ SIG: A Revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Type & Media 2018–19 ЯREthan Cohen ‡ Submitted as part of Paul van der Laan’s Revival class for the Master of Arts in Type & Media course at Koninklijke Academie von Beeldende Kunsten (Royal Academy of Art, The Hague) INTRODUCTION “I feel such a closeness to William Project Overview Morris that I always have the feeling Sig is a revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Halbfette. My primary source that he cannot be an Englishman, material was the Klingspor Kalender für das Jahr 1933 (Klingspor Calen- dar for the Year 1933), a 17.5 × 9.6 cm book set in various cuts of Wallau. he must be a German.” The Klingspor Kalender was an annual promotional keepsake printed by the Klingspor Type Foundry in Offenbach am Main that featured different Klingspor typefaces every year. This edition has a daily cal- endar set in Magere Wallau (Wallau Light) and an 18-page collection RUDOLF KOCH of fables set in 9 pt Wallau Halbfette (Wallau Semibold) with woodcut illustrations by Willi Harwerth, who worked as a draftsman at the Klingspor Type Foundry. -

Package Mathfont V. 1.6 User Guide Conrad Kosowsky December 2019 [email protected]

Package mathfont v. 1.6 User Guide Conrad Kosowsky December 2019 [email protected] For easy, off-the-shelf use, type the following in your docu- ment preamble and compile using X LE ATEX or LuaLATEX: \usepackage[hfont namei]{mathfont} Abstract The mathfont package provides a flexible interface for changing the font of math- mode characters. The package allows the user to specify a default unicode font for each of six basic classes of Latin and Greek characters, and it provides additional support for unicode math and alphanumeric symbols, including punctuation. Crucially, mathfont is compatible with both X LE ATEX and LuaLATEX, and it provides several font-loading commands that allow the user to change fonts locally or for individual characters within math mode. Handling fonts in TEX and LATEX is a notoriously difficult task. Donald Knuth origi- nally designed TEX to support fonts created with Metafont, and while subsequent versions of TEX extended this functionality to postscript fonts, Plain TEX's font-loading capabilities remain limited. Many, if not most, LATEX users are unfamiliar with the fd files that must be used in font declaration, and the minutiae of TEX's \font primitive can be esoteric and confusing. LATEX 2"'s New Font Selection System (nfss) implemented a straightforward syn- tax for loading and managing fonts, but LATEX macros overlaying a TEX core face the same versatility issues as Plain TEX itself. Fonts in math mode present a double challenge: after loading a font either in Plain TEX or through the nfss, defining math symbols can be unin- tuitive for users who are unfamiliar with TEX's \mathcode primitive. -

ISO Basic Latin Alphabet

ISO basic Latin alphabet The ISO basic Latin alphabet is a Latin-script alphabet and consists of two sets of 26 letters, codified in[1] various national and international standards and used widely in international communication. The two sets contain the following 26 letters each:[1][2] ISO basic Latin alphabet Uppercase Latin A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z alphabet Lowercase Latin a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z alphabet Contents History Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters Names for the two subsets Names for the letters Timeline for encoding standards Timeline for widely used computer codes supporting the alphabet Representation Usage Alphabets containing the same set of letters Column numbering See also References History By the 1960s it became apparent to thecomputer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin script in their (ISO/IEC 646) 7-bit character-encoding standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. The standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 8859 (8-bit character encoding) and ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin script with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.[1] Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters The Unicode block that contains the alphabet is called "C0 Controls and Basic Latin". -

The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing Writing Systems Using Orthography Profiles

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing writing systems using orthography profiles Moran, Steven ; Cysouw, Michael DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.290662 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-135400 Monograph The following work is licensed under a Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License. Originally published at: Moran, Steven; Cysouw, Michael (2017). The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing writing systems using orthography profiles. CERN Data Centre: Zenodo. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.290662 The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists Managing writing systems using orthography profiles Steven Moran & Michael Cysouw Change dedication in localmetadata.tex Preface This text is meant as a practical guide for linguists, and programmers, whowork with data in multilingual computational environments. We introduce the basic concepts needed to understand how writing systems and character encodings function, and how they work together. The intersection of the Unicode Standard and the International Phonetic Al- phabet is often not met without frustration by users. Nevertheless, thetwo standards have provided language researchers with a consistent computational architecture needed to process, publish and analyze data from many different languages. We bring to light common, but not always transparent, pitfalls that researchers face when working with Unicode and IPA. Our research uses quantitative methods to compare languages and uncover and clarify their phylogenetic relations. However, the majority of lexical data available from the world’s languages is in author- or document-specific orthogra- phies. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Punctuation Guide

Punctuation guide 1. The uses of punctuation Punctuation is an art, not a science, and a sentence can often be punctuated correctly in more than one way. It may also vary according to style: formal academic prose, for instance, might make more use of colons, semicolons, and brackets and less of full stops, commas, and dashes than conversational or journalistic prose. But there are some conventions you will need to follow if you are to write clear and elegant English. In earlier periods of English, punctuation was often used rhetorically—that is, to represent the rhythms of the speaking voice. The main function of modern English punctuation, however, is logical: it is used to make clear the grammatical structure of the sentence, linking or separating groups of ideas and distinguishing what is important in the sentence from what is subordinate. It can also be used to break up a long sentence into more manageable units, but this may only be done where a logical break occurs; Jane Austen's sentence ‗No one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy, would ever have supposed her born to be a heroine‘ would now lose its comma, since there is no logical break between subject and verb (compare: ‗No one would have supposed …‘). 2. The main stops and their functions The full stop, exclamation mark, and question mark are used to mark off separate sentences. Within the sentence, the colon (:) and semicolon (;) are stronger marks of division than the comma, brackets, and the dash. Properly used, the stops can be a very effective method of marking off the divisions and subdivisions of your argument; misused, they can make it barely intelligible, as in this example: ‗Donne starts the poem by poking fun at the Petrarchan convention; the belief that one's mistress's scorn could make one physically ill, he carries this one step further…‘. -

Punctuate Your Translation Text Right: a View From

Title of article: Decoding and Encoding the Discourse meaning of Punctuation: a Perspective from English-to-Chinese Translation Author: Dr Caiwen Wang, University of Westminster, London, UK Email: [email protected] - 1 - Decoding and Encoding the Discourse meaning of Punctuation: a Perspective from English-to-Chinese Translation Abstract: This exploratory research examines translation students’ use of punctuation, by applying Newmark’s (1988) classical idea of punctuation as a discourse unit for meaning demarcation. Data was collected from a group of 25 Chinese students studying specialised translation at a British university. The research focuses on the use of two punctuation marks: comma and period or full stop. The aim is to investigate how students of translation analyse the meaning of a source text with punctuation marks and how they subsequently convert this meaning into the target language again using punctuation marks. It is found that students generally do not mechanically copy the punctuation marks of a source text into the translation. They will customize or modify the original punctuation marks according to their meaning analysis of the text and their knowledge of punctuation in source and target languages. Finally, we will discuss the implications of the research for translation education. Key words: Punctuation; semantic relationship; discourse; translation pedagogy 1. Introduction This research is an attempt to enrich data for filling the gap summarised by Rodríguez-Castro, which is that ‘[i]n the scholarly research in Translation Studies, the study of punctuation has not attracted much attention either from professionals or from researchers’ (2011:43). The research especially draws inspiration from a Master student doing her end-of-year Translation Project, where she and I, as her supervisor, discussed punctuation use in depth. -

Threshold Digraphs

Volume 119 (2014) http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/jres.119.007 Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology Threshold Digraphs Brian Cloteaux1, M. Drew LaMar2, Elizabeth Moseman1, and James Shook1 1National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 20899 2The College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA 23185 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] A digraph whose degree sequence has a unique vertex labeled realization is called threshold. In this paper we present several characterizations of threshold digraphs and their degree sequences, and show these characterizations to be equivalent. Using this result, we obtain a new, short proof of the Fulkerson-Chen theorem on degree sequences of general digraphs. Key words: digraph realizations; Fulkerson-Chen theorem; threshold digraphs. Accepted: May 6, 2014 Published: May 20, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/jres.119.007 1. Introduction Creating models of real-world networks, such as social and biological interactions, is a central task for understanding and measuring the behavior of these networks. A usual first step in this type of model creation is to construct a digraph with a given degree sequence. We examine the extreme case of digraph construction where for a given degree sequence there is exactly one digraph that can be created. What follows is a brief introduction to the notation used in the paper. For notation not otherwise defined, see Diestel [1]. We let G=( VE , ) be a digraph where E is a set of ordered pairs called arcs. If (,vw )∈ E, then we say w is an out-neighbor of v and v is an in-neighbor of w.