Creativity Or Creativities: a Study of Domain Generality and Specificity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xamk Opinnäytteen Kirjoitusalusta Versio 14022017

Essi Tommila CREATING A CHILDREN’S GAMIFIED PICTURE BOOK Bachelor’s thesis Game Design 2018 Author Degree Time Essi Tommila Bachelor of Culture April 2018 and Arts Title 41 pages Creating a children’s gamified picture book 2 pages of appendices Commissioned by - Supervisor Marko Siitonen Sarah-Jane Leavey Abstract This thesis was based on the game The Little Cat and The Rainbow Egg which is an interactive gamified storybook for children from the ages of 5 to 10. The game was published on Google Play and can be played with a tablet or a phone. The purpose of this thesis project was to work as a showcase of the idea of creating a well- functioning picture book for children with gamified elements that enhance the immersion of storytelling. The goal was to make a professional and functional product with emphasis on the visual style. The game was produced by three people, programming and music were done by outside partners, the author was working as a lead designer and artist. The design and idea of the product is based on theoretical backgrounds that are presented in the first part of the thesis. This thesis report answers to the questions how to gamify a storybook and how to illustrate and add interactive elements to a story so that it works as a children’s medium. The thesis report focuses on the process of making the project from the design standpoint and the main topics include interactive illustration, visual directing, children’s illustration, and publishing of the product. Other notable things the report talks about are storyboarding, art, stylizing of illustrations and technical development such as programming, animation and music. -

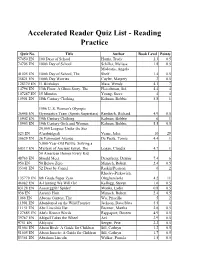

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz No. Title Author Book Level Points 57450 EN 100 Days of School Harris, Trudy 2.3 0.5 74705 EN 100th Day of School Schiller, Melissa 1.8 0.5 Medearis, Angela 41025 EN 100th Day of School, The Shelf 1.4 0.5 35821 EN 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 3 0.5 128370 EN 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 4.1 7 14796 EN 13th Floor: A Ghost Story, The Fleischman, Sid 4.4 4 107287 EN 15 Minutes Young, Steve 4 4 15901 EN 18th Century Clothing Kalman, Bobbie 5.8 1 1996 U. S. Women's Olympic 26445 EN Gymnastics Team (Sports Superstars) Rambeck, Richard 4.9 0.5 15902 EN 19th Century Clothing Kalman, Bobbie 6 1 15903 EN 19th Century Girls and Women Kalman, Bobbie 5.5 0.5 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea 523 EN (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10 28 30629 EN 26 Fairmount Avenue De Paola, Tomie 4.4 1 5,000-Year-Old Puzzle: Solving a 60317 EN Mystery of Ancient Egypt, The Logan, Claudia 4.7 1 50 American Heroes Every Kid 48763 EN Should Meet Denenberg, Dennis 7.4 6 950 EN 50 Below Zero Munsch, Robert 2.4 0.5 35341 EN 52 Days by Camel Raskin/Pearson 6 2 Rhuday-Perkovich, 135779 EN 8th Grade Super Zero Olugbemisola 4.2 11 46082 EN A-Hunting We Will Go! Kellogg, Steven 1.6 0.5 83128 EN Aaaarrgghh! Spider! Monks, Lydia 0.8 0.5 936 EN Aaron's Hair Munsch, Robert 2.4 0.5 1068 EN Abacus Contest, The Wu, Priscilla 5 2 11901 EN Abandoned on the Wild Frontier Jackson, Dave/Neta 5.5 4 11151 EN Abe Lincoln's Hat Brenner, Martha 2.6 0.5 127685 EN Abe's Honest Words Rappaport, Doreen 4.9 0.5 39787 EN Abigail Takes the Wheel Avi 2.9 0.5 9751 EN Abiyoyo Seeger, Pete 2.2 0.5 51004 EN About Birds: A Guide for Children Sill, Cathryn 1.2 0.5 51005 EN About Insects: A Guide for Children Sill, Cathryn 1.7 0.5 83361 EN Abraham Lincoln Walker, Pamela 1.5 0.5 Abraham Lincoln (Famous 31812 EN Americans) Schaefer, Lola M. -

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 945 EN 12 Dancing Princesses, The Littledale, Freya 3.8 0.5 11101 16th Century Mosque, A MacDonald, Fiona 7.7 1.0 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 116316 1918 Flu Pandemic, The Krohn, Katherine 4.6 0.5 EN 523 EN 20,000 Leagues under the Sea Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 971 EN 50 Below Zero Munsch, Robert 2.0 0.5 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 11001 A-is for Africa Onyefulu, Ifeoma 4.5 0.5 EN 17601 Abe Lincoln: Log Cabin to White House North, Sterling 8.4 4.0 EN 127685 Abe's Honest Words Rappaport, Doreen 4.9 0.5 EN 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 5.9 3.0 900378 Aboard the Underground Railroad (MH Otfinoski, Steven 6.2 0.5 EN Edition) 86635 Abominable Snowman Doesn't Roast Dadey, Debbie 4.0 1.0 EN Marshmallows, The 815 EN Abraham Lincoln Stevenson, Augusta 3.5 3.0 42301 Abraham Lincoln Welsbacher, Anne 5.0 0.5 Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

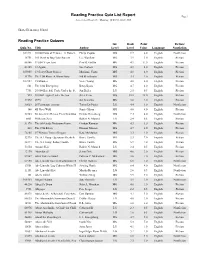

AR List by Title

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Monday, 10/04/10, 08:21 AM Shasta Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 102321 10,000 Days of Thunder: A History of thePhilip Vietnam Caputo War MG 9.7 6.0 English Nonfiction 18751 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw MG 3.9 5.0 English Fiction 86346 11,000 Years Lost Peni R. Griffin MG 4.9 11.0 English Fiction 61265 12 Again Sue Corbett MG 4.9 8.0 English Fiction 105005 13 Scary Ghost Stories Marianne Carus MG 4.8 4.0 English Fiction 14796 The 13th Floor: A Ghost Story Sid Fleischman MG 4.4 4.0 English Fiction 107287 15 Minutes Steve Young MG 4.0 4.0 English Fiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.7 4.0 English Fiction 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea Jon Buller LG 2.5 0.5 English Fiction 523 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Jules Verne MG 10.0 28.0 English Fiction 11592 2095 Jon Scieszka MG 3.8 1.0 English Fiction 30629 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola LG 4.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 166 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson MG 4.6 4.0 English Fiction 48763 50 American Heroes Every Kid Should DennisMeet Denenberg MG 7.4 6.0 English Nonfiction 8001 50 Below Zero Robert N. Munsch LG 2.4 0.5 English Fiction 31170 The 6th Grade Nickname Game Gordon Korman MG 4.3 3.0 English Fiction 413 The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson MG 4.7 2.0 English Fiction 76205 97 Ways to Train a Dragon Kate McMullan MG 3.3 2.0 English Fiction 32378 The A.I. -

Sacro E Profano (Filth and Wisdom)

NANNI MORETTI presenta SACRO E PROFANO (FILTH AND WISDOM) un film di MADONNA USCITA 12 GIUGNO 2009 Ufficio stampa: Valentina Guidi tel. 335.6887778 – [email protected] Mario Locurcio tel. 335.8383364 – [email protected] www.guidilocurcio.it SACRO E PROFANO (Filth and Wisdom) Un film di Madonna Scritto da Madonna & Dan Cadan Produttore esecutivo Madonna Prodotto da Nicola Doring Produttore associato Angela Becker Fotografia Tim Maurice Jones Montaggio Russell Icke Scene Gideon Ponte Costumi B. PERSONAGGI E INTERPRETI A.K. Eugene Hutz Holly Holly Weston Juliette Vicky McClure Professor Flynn Richard E. Grant Sardeep Inder Manocha Uomo d'affari Elliot Levey Francine Francesca Kingdon Chloe Clare Wilkie Harry Beechman Stephen Graham Moglie dell'uomo d'affari Hannah Walters Moglie di Sardeep Shobu Kapoor DJ Ade Lorcan O’Niell Guy Henry Nunzio Nunzio Palmara Mr Frisk Tim Wallers Padre di A.K. Olegar Fedorov Giovane A.K. Luca Surguladze Mikey Steve Allen Durata: 80’ I materiali stampa sono disponibili sul sito www.guidilocurcio.it 2 SACRO E PROFANO (Filth and Wisdom) SINOSSI A.K. (Eugene Hutz) è un musicista costretto a soddisfare i fantasmi sadomaso dei suoi clienti per poter finanziare le prove del suo gruppo punk-gitano. Juliette (Vicky McClure) lavora in farmacia ma sogna di fare la volontaria in Africa. Holly (Holly Weston) è una ballerina classica che, per pagare l'affitto, inizia una carriera inaspettatamente brillante come lap dancer. Attorno a loro una Londra colorata, multietnica, abitata da personaggi folkloristici. Un film eccentrico, ironico, che racconta storie uniche e universali attraverso la vita quotidiana - buffa, a volte tragica, ma sempre terribilmente autentica - dei suoi protagonisti. -

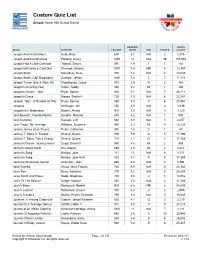

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Forest Hills School District MANAGEMENT READING WORD BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL GRL POINTS COUNT Joseph And His Brothers Auld, Mary 690 4.1 N/A 2 1,376 Joseph Andrews/Shamela Fielding, Henry 1200 12 N/A 39 165,998 Joseph Had A Little Overcoat Taback, Simms BR 1.9 I 1 182 Joseph McCarthy & Cold War Sherrow, Victoria 1070 7.4 NR 6 13,397 Joseph Stalin McCollum, Sean 970 7.6 N/A 6 13,030 Joseph Stalin (A&E Biography) Zuehlke, Jeffrey 1030 7.4 Z 7 17,172 Joseph Turner (Life & Work Of) Woodhouse, Jayne 470 2.5 N 2 764 Joseph's Amazing Coat Slater, Teddy 480 3.2 M 1 455 Joseph's Choice - 1861 Pryor, Bonnie 630 5.1 N/A 7 26,711 Joseph's Grace Moses, Shelia P. 730 5.5 N/A 8 22,241 Joseph: 1861 - A Rumble Of War Pryor, Bonnie 680 5.3 V 6 27,451 Josepha McGugan, Jim 550 3.5 N/A 2 1,339 Josephine's 'Magination Dobrin, Arnold N/A 3.5 N/A 3 3,129 Josh Beckett...Florida Marlins Sandler, Michael 680 4.2 N/A 1 994 Josh Hamilton Savage, Jeff 660 3.8 N/A 3 2,257 Josh Taylor, Mr. Average Williams, Suzanne 580 3.3 M 5 10,233 Joshua James Likes Trucks Petrie, Catherine BR 1.4 C 1 47 Joshua T. Bates In Trouble... Shreve, Susan 890 5.9 Q 5 17,196 Joshua T. Bates Takes Charge Shreve, Susan 710 4.1 Q 4 17,468 Joshua's Dream: Journey-Israel Segal, Sheila F. -

AR List by Book Level

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Monday, 10/04/10, 08:24 AM Shasta Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 41166 All Kinds of Flowers Teresa Turner LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 41167 Amazing Birds of the Rain Forest Claire Daniel LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 42378 The Apple Pie Family Gare Thompson LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 41168 Arctic Life F. R. Robinson LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 41178 The Around-the-World Lunch Yanitzia Canetti LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 42373 Beach Creatures Michael K. Smith LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 41169 Buddy Butterfly and His Cousin Melissa Blackwell Burke LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 41164 A Butterfly's Life Melissa Blackwell Burke LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 41170 Castles Alice Leonhardt LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 42374 Dinosaur Fun Facts Ellen Keller LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 41179 The Early Bird's Alarm Clock Claire Daniel LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 41171 Every Flower Is Beautiful Teresa Turner LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 41172 Festival Foods Around the World Becky Stull LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 42375 I Can Be Anything Ena Keo LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 41173 In Hiding: Animals Under Cover Melissa Blackwell Burke LG 0.0 0.5 English Nonfiction 41174 In the Land of the Polar Bear F. R. -

The English Roses: Catch the Bouquet Free

FREE THE ENGLISH ROSES: CATCH THE BOUQUET PDF Madonna | 128 pages | 01 Apr 2010 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780142411292 | English | New York, NY, United Kingdom The English Roses Series in Order by Madonna - FictionDB Please sign in to write a review. If you have changed your email address then contact us and we will The English Roses: Catch the Bouquet your details. Would you like to proceed to the App store to download the Waterstones App? We have recently updated our Privacy Policy. The site uses cookies to offer you The English Roses: Catch the Bouquet better experience. By continuing to browse the site you accept our Cookie Policy, you can change your settings at any time. Not available This product is currently unavailable. This item has been added to your basket View basket Checkout. The Roses couldn't be happier for their teacher, or for Binah, whose The English Roses: Catch the Bouquet mother died when she was just a baby. Binah is thrilled at the idea of having a stepmother like Miss F, until she realizes that a new woman in her father'slife means less time for Binah. Binah misses her father terribly. And it doesn't help that Charlotte is driving everyone nuts trying to plan the perfect wedding. Can the English Roses save this walk down the aisle from going totally awry? Added to basket. The Worst Witch. Jill Murphy. Lies Like Poison. Chelsea Pitcher. Future Friend. David Baddiel. Isadora Moon Goes to a Wedding. Harriet Muncaster. My Life as a Cat. Carlie Sorosiak. The Book of Hopes. -

Home-Start Banbury & Chipping Norton

HOOK NORTON NEWSLETTER February 2007 Series 32 No 1 An Independent estate agency offering an unrivalled coverage of your village Hook Norton ● Specializing in the Sale and Rental of Village and Country Homes, backed by many years of local experience You are invited to receive a Free Market Appraisal of your Home. 16 New Street, Chipping Norton Oxfordshire Residential Sales: (01608) 644886 Residential Lettings: (01295) 275882 www ,havwardwhite,co, uk 2 FROM THE EDITORS NEWSLETTER TEAM This month, the Newsletter has Advertising: Judi Leader 730609 received donations totalling £44.76. Distribution: Malcolm Black As well as donations in the Post Office Proof Reading: Nigel Lehmann Newsletter box, several donations IT/Web Support: Martin Baxter have been received via our Paypal Treasurer: account ([email protected]) Directory: Diana Barber 737428 Thank you. Sadly we report the deaths of Stanley Maurice Cox, of Swerford, aged 77 years, George Hummer late of Hook Norton and Elizabeth Anne Moore, aged 80 years. On behalf of the village we send our condolences to their families and friends. We welcome Malcolm Black to the Newsletter. Malcolm has taken over the distribution from Bunty – thank you Malcolm. Finally, we thank John Burke from Southampton for the postcard on the cover showing the Flower Show in 1913. John writes 'I have a picture of the Hook Norton Flower show in 1913, produced as a postcard. I inherited it from my grandmother, who appears in the picture together with friends who lived in Hook Norton; the now rather faint text on the reverse is a note to my great grandmother in Winchester (where my grandmother lived)'. -

2005 ELEM Cover

P ERMA-PICKS O N EW A ND N OTABLES O F ALL 2005 PHONE: 800-637-6581 FAX: 800-551-1169 www.perma-bound.com [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS PERMA-PREVIEWS AL CAPONE DOES MY SHIRTS By Gennifer Choldenko 1 GRANITE BABY By Lynne Bertrand 2 LEAPING BEAUTY AND OTHER ANIMAL FAIRY TALES By Gregory Maguire 3 NEW TITLES Annotated Index 4-15 Nonfiction, by Dewey 4-8 Fiction, by Author 8-12 Easy, by Author 12-15 Title Index 16-23 THEMES - RECONNECTING Education 24-25 Relationships 25 Responsibilities 26 STARRED REVIEWS SLJ Starred Reviews 28 Booklist Starred Reviews 29 LIBRARY SERVICES 30-31 ORDER FORM 32 PUBLISHER KEY, REVIEW SOURCES KEY, CALL NUMBER KEY Inside Back Cover InteractiveInteractive CatalogCatalog OnlineOnline AtAt www.perma-bound.com We welcome your ideas, suggestions and comments. Write us at [email protected] PUBLISHERS’ KEY ALD Aladdin GRNP Greenhaven Press, NORT NorthWord Press Jacksonville, Illinois 62650 617 E. Road Vandalia PERMA-BOUND BOOKS AT Atheneum Inc. ORCA Orca Press FIRST CLASS MAIL PERMIT NO. IL 62650 152 JACKSONVILLE, BUSINESS REPLY MAIL REPLY BUSINESS AUCR Audiocraft GRO Groundwood Books ORCH Orchard Books B Bantam Books, Inc. HA HarperCollins PANA PanAmerican POSTAGE WILL BE PAID BY ADDRESSEE WILL BE PAID POSTAGE BARE Barefoot Books HB Harcourt Brace Publishing BEA Beacon (Jovanovich) PC Pleasant Company BOYD Boyds Mills Press HH Holiday House PEAC Peachtree Publishers CAND Candlewick Press HM Houghton Mifflin PEL Pelican Publishing Co. CHAR Charlesbridge HNA Harry N. Abrams, Inc. PU G.P.Putnam’s Sons Publishing HOLT Henry Holt & Co. -

MADONNA E OS MEIOS MASSIVOS DE COMUNICAÇÃO: Pactos Para a Construção De Uma Persona

UNIVERSIDADE ANHEMBI MORUMBI VALESKA FONSECA NAKAD MADONNA E OS MEIOS MASSIVOS DE COMUNICAÇÃO: Pactos Para a Construção de Uma Persona SÃO PAULO 2008 VALESKA FONSECA NAKAD MADONNA E OS MEIOS MASSIVOS DE COMUNICAÇÃO: Pactos Para a Construção de Uma Persona Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada à Banca Examinadora, como exigência parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre do Programa de Mestrado em Comunicação área de concentração em Comunicação Contemporânea da Universidade Anhembi Morumbi, sob a orientação do Prof. Dr.Vicente Gosciola. SÃO PAULO 2008 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço ao Professor Dr. Vicente Gosciola, meu orientador, exemplo de dedicação e competência que me inspirou, cuja serenidade foi essencial para que eu acreditasse que esse trabalho seria possível. Agradeço ao Professor Dr. Gelson Santana, modelo de excelência no ensino, que me revelou outras perspectivas e me conduziu por caminhos nunca percorridos para a elaboração das minhas correlações entre a comunicação contemporânea e a moda. Agradeço igualmente ao Prof. Dr. Sérgio Basbaum pelas observações valiosas na banca de qualificação. À Profa. Dra. Bernadette Lyra pelo conhecimento passado em cada encontro, pelo entusiasmo, carinho e dedicação ao Programa de Mestrado e sua primeira turma. Ao Prof. Dr. Rogério Ferraraz , Profa. Dra. Maria Ignês Carlos Magno, e ao Prof. Dr. Marcelo Tassara, modelos de seriedade, que tanto contribuíram com suas aulas e conselhos, e com quem a convivência foi sempre tão doce e agradável. Aos demais professores e funcionários do Programa de Mestrado em Comunicação, também, muito obrigada. Aos meus pais, Berenice Fonseca Nakad e Jamil Nakad, agradeço pelo amor e dedicação de uma vida toda. Pelo estímulo e financiamento dos meus estudos e minhas viagens em busca de cultura e conhecimento. -

Author (4).Xlsx

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz No. Author Title Book Level Points Anansi Does the Impossible! An 17504 EN Aardema, Verna Ashanti Tale 3.2 0.5 9758 EN Aardema, Verna Bringing the Rain to Kapiti Plain 4.6 0.5 Koi and the Kola Nuts: A Tale from 46144 EN Aardema, Verna Liberia 4 0.5 4335 EN Abbink, Emily Colors of the Navajo 5.6 0.5 116809 EN Abbink, Emily Monterey Bay Area Missions 5.1 1 39800 EN Abbott, Tony City in the Clouds 3.2 1 106747 EN Abbott, Tony Firegirl 4.1 4 54492 EN Abbott, Tony Golden Wasp, The 3.1 1 39828 EN Abbott, Tony Great Ice Battle, The 3 1 Hidden Stairs and the Magic Carpet, 39829 EN Abbott, Tony The 2.9 1 39812 EN Abbott, Tony Journey to the Volcano Palace 3.1 1 101890 EN Abbott, Tony Kringle 4.8 10 65672 EN Abbott, Tony Magic Escapes, The 3.7 2 54497 EN Abbott, Tony Mask of Maliban, The 3.7 2 39831 EN Abbott, Tony Mysterious Island, The 3 1 121312 EN Abbott, Tony Postcard, The 4 9 54487 EN Abbott, Tony Quest for the Queen 3.3 1 39832 EN Abbott, Tony Sleeping Giant of Goll, The 3 1 89002 EN Abela, Deborah Mission: Spy Force Revealed 6 8 74368 EN Aberg, Rebecca Map Keys 2 0.5 131259 EN Aboff, Marcie If You Were a Polygon 2.6 0.5 131261 EN Aboff, Marcie If You Were a Triangle 2.9 0.5 123600 EN Aboff, Marcie If You Were an Even Number 2.7 0.5 123601 EN Aboff, Marcie If You Were an Odd Number 2.9 0.5 83362 EN Abraham, Philip Amelia Earhart 1.5 0.5 83363 EN Abraham, Philip Christopher Reeve 1.3 0.5 20659 EN Ackerman, Karen Araminta's Paint Box 5.2 0.5 5490 EN Ackerman, Karen Song and Dance Man 4 0.5