Building a Culture of Care in Classrooms Aften Ballem B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xamk Opinnäytteen Kirjoitusalusta Versio 14022017

Essi Tommila CREATING A CHILDREN’S GAMIFIED PICTURE BOOK Bachelor’s thesis Game Design 2018 Author Degree Time Essi Tommila Bachelor of Culture April 2018 and Arts Title 41 pages Creating a children’s gamified picture book 2 pages of appendices Commissioned by - Supervisor Marko Siitonen Sarah-Jane Leavey Abstract This thesis was based on the game The Little Cat and The Rainbow Egg which is an interactive gamified storybook for children from the ages of 5 to 10. The game was published on Google Play and can be played with a tablet or a phone. The purpose of this thesis project was to work as a showcase of the idea of creating a well- functioning picture book for children with gamified elements that enhance the immersion of storytelling. The goal was to make a professional and functional product with emphasis on the visual style. The game was produced by three people, programming and music were done by outside partners, the author was working as a lead designer and artist. The design and idea of the product is based on theoretical backgrounds that are presented in the first part of the thesis. This thesis report answers to the questions how to gamify a storybook and how to illustrate and add interactive elements to a story so that it works as a children’s medium. The thesis report focuses on the process of making the project from the design standpoint and the main topics include interactive illustration, visual directing, children’s illustration, and publishing of the product. Other notable things the report talks about are storyboarding, art, stylizing of illustrations and technical development such as programming, animation and music. -

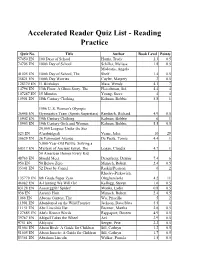

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz No. Title Author Book Level Points 57450 EN 100 Days of School Harris, Trudy 2.3 0.5 74705 EN 100th Day of School Schiller, Melissa 1.8 0.5 Medearis, Angela 41025 EN 100th Day of School, The Shelf 1.4 0.5 35821 EN 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 3 0.5 128370 EN 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 4.1 7 14796 EN 13th Floor: A Ghost Story, The Fleischman, Sid 4.4 4 107287 EN 15 Minutes Young, Steve 4 4 15901 EN 18th Century Clothing Kalman, Bobbie 5.8 1 1996 U. S. Women's Olympic 26445 EN Gymnastics Team (Sports Superstars) Rambeck, Richard 4.9 0.5 15902 EN 19th Century Clothing Kalman, Bobbie 6 1 15903 EN 19th Century Girls and Women Kalman, Bobbie 5.5 0.5 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea 523 EN (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10 28 30629 EN 26 Fairmount Avenue De Paola, Tomie 4.4 1 5,000-Year-Old Puzzle: Solving a 60317 EN Mystery of Ancient Egypt, The Logan, Claudia 4.7 1 50 American Heroes Every Kid 48763 EN Should Meet Denenberg, Dennis 7.4 6 950 EN 50 Below Zero Munsch, Robert 2.4 0.5 35341 EN 52 Days by Camel Raskin/Pearson 6 2 Rhuday-Perkovich, 135779 EN 8th Grade Super Zero Olugbemisola 4.2 11 46082 EN A-Hunting We Will Go! Kellogg, Steven 1.6 0.5 83128 EN Aaaarrgghh! Spider! Monks, Lydia 0.8 0.5 936 EN Aaron's Hair Munsch, Robert 2.4 0.5 1068 EN Abacus Contest, The Wu, Priscilla 5 2 11901 EN Abandoned on the Wild Frontier Jackson, Dave/Neta 5.5 4 11151 EN Abe Lincoln's Hat Brenner, Martha 2.6 0.5 127685 EN Abe's Honest Words Rappaport, Doreen 4.9 0.5 39787 EN Abigail Takes the Wheel Avi 2.9 0.5 9751 EN Abiyoyo Seeger, Pete 2.2 0.5 51004 EN About Birds: A Guide for Children Sill, Cathryn 1.2 0.5 51005 EN About Insects: A Guide for Children Sill, Cathryn 1.7 0.5 83361 EN Abraham Lincoln Walker, Pamela 1.5 0.5 Abraham Lincoln (Famous 31812 EN Americans) Schaefer, Lola M. -

Children's Literature Bibliographies: Enid Blyton Bibliography, Mercer Mayer Bibliography, List of Works

JQFJQ6OTWVUW > Doc « Children's literature bibliographies: Enid Blyton bibliography, Mercer Mayer bibliography, List of works... Children's literature bibliographies: Enid Blyton bibliography, Mercer Mayer bibliography, List of works by Mary Martha Sherwood, Madonna bibliography, Colin Thiele bibliography, Roald Dahl short stor Filesize: 6.34 MB Reviews This is an amazing book that I actually have actually read through. I am quite late in start reading this one, but better then never. You will not truly feel monotony at anytime of the time (that's what catalogs are for concerning should you ask me). (Scottie Schroeder DDS) DISCLAIMER | DMCA ISBVZA3DCRMK // PDF \ Children's literature bibliographies: Enid Blyton bibliography, Mercer Mayer bibliography, List of works... CHILDREN'S LITERATURE BIBLIOGRAPHIES: ENID BLYTON BIBLIOGRAPHY, MERCER MAYER BIBLIOGRAPHY, LIST OF WORKS BY MARY MARTHA SHERWOOD, MADONNA BIBLIOGRAPHY, COLIN THIELE BIBLIOGRAPHY, ROALD DAHL SHORT STOR Books LLC, Wiki Series, 2016. Paperback. Book Condition: New. PRINT ON DEMAND Book; New; Publication Year 2016; Not Signed; Fast Shipping from the UK. No. book. Read Children's literature bibliographies: Enid Blyton bibliography, Mercer Mayer bibliography, List of works by Mary Martha Sherwood, Madonna bibliography, Colin Thiele bibliography, Roald Dahl short stor Online Download PDF Children's literature bibliographies: Enid Blyton bibliography, Mercer Mayer bibliography, List of works by Mary Martha Sherwood, Madonna bibliography, Colin Thiele bibliography, Roald Dahl short stor ZSSS4MUFT54W » eBook < Children's literature bibliographies: Enid Blyton bibliography, Mercer Mayer bibliography, List of works... Related eBooks Edge] the collection stacks of children's literature: Chunhyang Qiuyun 1.2 --- Children's Literature 2004(Chinese Edition) paperback. Book Condition: New. -

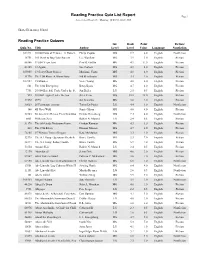

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 945 EN 12 Dancing Princesses, The Littledale, Freya 3.8 0.5 11101 16th Century Mosque, A MacDonald, Fiona 7.7 1.0 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 116316 1918 Flu Pandemic, The Krohn, Katherine 4.6 0.5 EN 523 EN 20,000 Leagues under the Sea Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 971 EN 50 Below Zero Munsch, Robert 2.0 0.5 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 11001 A-is for Africa Onyefulu, Ifeoma 4.5 0.5 EN 17601 Abe Lincoln: Log Cabin to White House North, Sterling 8.4 4.0 EN 127685 Abe's Honest Words Rappaport, Doreen 4.9 0.5 EN 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 5.9 3.0 900378 Aboard the Underground Railroad (MH Otfinoski, Steven 6.2 0.5 EN Edition) 86635 Abominable Snowman Doesn't Roast Dadey, Debbie 4.0 1.0 EN Marshmallows, The 815 EN Abraham Lincoln Stevenson, Augusta 3.5 3.0 42301 Abraham Lincoln Welsbacher, Anne 5.0 0.5 Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

AR List by Title

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Monday, 10/04/10, 08:21 AM Shasta Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 102321 10,000 Days of Thunder: A History of thePhilip Vietnam Caputo War MG 9.7 6.0 English Nonfiction 18751 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw MG 3.9 5.0 English Fiction 86346 11,000 Years Lost Peni R. Griffin MG 4.9 11.0 English Fiction 61265 12 Again Sue Corbett MG 4.9 8.0 English Fiction 105005 13 Scary Ghost Stories Marianne Carus MG 4.8 4.0 English Fiction 14796 The 13th Floor: A Ghost Story Sid Fleischman MG 4.4 4.0 English Fiction 107287 15 Minutes Steve Young MG 4.0 4.0 English Fiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.7 4.0 English Fiction 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea Jon Buller LG 2.5 0.5 English Fiction 523 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Jules Verne MG 10.0 28.0 English Fiction 11592 2095 Jon Scieszka MG 3.8 1.0 English Fiction 30629 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola LG 4.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 166 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson MG 4.6 4.0 English Fiction 48763 50 American Heroes Every Kid Should DennisMeet Denenberg MG 7.4 6.0 English Nonfiction 8001 50 Below Zero Robert N. Munsch LG 2.4 0.5 English Fiction 31170 The 6th Grade Nickname Game Gordon Korman MG 4.3 3.0 English Fiction 413 The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson MG 4.7 2.0 English Fiction 76205 97 Ways to Train a Dragon Kate McMullan MG 3.3 2.0 English Fiction 32378 The A.I. -

Problems with Bittorrent Litigation in the United States: Personal Jurisdiction, Joinder, Evidentiary Issues, and Why the Dutch Have a Better System

Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 13 Issue 1 2014 Problems with BitTorrent Litigation in the United states: Personal Jurisdiction, Joinder, Evidentiary Issues, and Why the Dutch Have a Better System Violeta Solonova Foreman Washington University in St. Louis, School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Violeta Solonova Foreman, Problems with BitTorrent Litigation in the United states: Personal Jurisdiction, Joinder, Evidentiary Issues, and Why the Dutch Have a Better System, 13 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 127 (2014), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol13/iss1/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROBLEMS WITH BITTORRENT LITIGATION IN THE UNITED STATES: PERSONAL JURISDICTION, JOINDER, EVIDENTIARY ISSUES, AND WHY THE DUTCH HAVE A BETTER SYSTEM INTRODUCTION In 2011, 23.76% of global internet traffic involved downloading or uploading pirated content, with BitTorrent accounting for an estimated 17.9% of all internet traffic.1 In the United States alone, 17.53% of internet traffic consists of illegal downloading.2 Despite many crackdowns, illegal downloading websites continue to thrive,3 and their users include some of their most avid opponents.4 Initially the Recording Industry Association of America (the “RIAA”) took it upon itself to prosecute individuals who 1. -

Reading Sample

BASQUIAT BOOM FOR REAL 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 1 20.11.19 14:31 EDITED BY DIETER BUCHHART AND ELEANOR NAIRNE WITH LOTTE JOHNSON 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 2 20.11.19 14:31 BASQUIAT BOOM FOR REAL PRESTEL MUNICH · LONDON · NEW YORK 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 3 20.11.19 14:31 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 4 20.11.19 14:31 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 5 20.11.19 14:31 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 6 20.11.19 14:31 8 FOREWORD JANE ALISON 4. JAZZ 12 BOOM, BOOM, BOOM FOR REAL 156 INTRODUCTION DIETER BUCHHART 158 BASQUIAT, BIRD, BEAT AND BOP 20 THE PERFORMANCE OF FRANCESCO MARTINELLI JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT ELEANOR NAIRNE 162 WORKS 178 ARCHIVE 1. SAMO© 5. ENCYCLOPAEDIA 28 INTRODUCTION 188 INTRODUCTION 30 THE SHADOWS 190 BASQUIAT’S BOOKS CHRISTIAN CAMPBELL ELEANOR NAIRNE 33 WORKS 194 WORKS 58 ARCHIVE 224 ARCHIVE 2. NEW YORK/ 6. THE SCREEN NEW WAVE 232 INTRODUCTION 66 INTRODUCTION 234 SCREENS, STEREOTYPES, SUBJECTS JORDANA MOORE SAGGESE 68 EXHIBITIONISM CARLO MCCORMICK 242 WORKS 72 WORKS 252 ARCHIVE 90 ARCHIVE 262 INTERVIEW BETWEEN 3. THE SCENE JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, GEOFF DUNLOP AND SANDY NAIRNE 98 INTRODUCTION 268 CHRONOLOGY 100 SAMO©’S NEW YORK LOTTE JOHNSON GLENN O’BRIEN 280 ENDNOTES 104 WORKS 288 INDEX 146 ARCHIVE 294 AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES 295 IMAGE CREDITS 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 7 20.11.19 14:31 Edo Bertoglio. Jean-Michel Basquiat wearing an American football helmet, 1981. 8 191115_Basquiat_Book_Spreads.indd 8 20.11.19 14:31 FOREWORD JANE ALISON Jean-Michel Basquiat is one of the most significant painters This is therefore a timely presentation of a formidable talent of the 20th century; his name has become synonymous with and builds on an important history of Basquiat exhibitions notions of cool. -

Dear Students and Parents, Welcome to the Fourth Grade! This Year

Dear Students and Parents, Welcome to the fourth grade! This year, your child will continue to be exposed to the team teaching model where each student is assigned to a peer learning group. In addition to completing two book reports, the students will be engaging in a variety of exciting yet challenging projects. The iPad lab will be used to conduct research on the Internet and to create projects. Class participation, organization, and responsibility are target goals which are emphasized throughout the fourth grade year. We look forward to having a fantastic and productive year with your child in our classes. As teachers, we strongly believe in the importance of parental involvement in a student’s education. Therefore, we are sure that your child will receive the best possible education with all of us working together as a team. Enjoy your summer! Sincerely, The Fourth Grade Team 4th Grade Suggested Entrance Skills Math Master fact families dealing with addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division facts. Solve basic and multi-step word problems (addition, subtraction and multiplication). Read current time and determine elapsed time using analog clock. Read, write and identify: o Dollars and cents formats o Numbers and place values up to 1,000,000 o Simple fractions (1/2, 1/3, 1/4, 1/5) Social Studies Recognize and find United States on a map of the world. Know the names of the oceans and continents of the world. Recognize states and capitals of the United States. Use general map skills including key, compass rose, and scale. Writing Use proper capitalization and punctuation marks to write a complete sentence. -

The Summer Reading Assignment Will Be Counted As Three Homework Grades (One Grade Per Book Read) and Will Be Due on August 23, 2019

Assignment Share one of the following with your teacher: • SCCPSS Reading log (Use your own paper for the response if you need more space) • myOn on-line reading report – free online reading offered by Get Georgia Reading • Copy of completed Barnes & Noble reading log (3 titles required for SCCPSS credit) • Copy of completed Live Oaks “A Universe of Stories” Early Literacy or Kids & Teens Activity Log Summer Reading for students entering Kindergarten is recommended, but not required. No grades will be given to kindergarten students. Students entering 1st Grade through 5th Grade this fall should read 3 books that fall within their Lexile range, from 100 points below to 50 points above their Lexile score. The Lexile score is found on the MAP reports, which were sent home to parents. Students are strongly encouraged to read at least one piece of informational (non-fiction) text over the summer. Georgia standards place a strong emphasis on informational text as students are prepared for success in college and career reading. Note: If your child’s Lexile score exceeds that of the Grade Level Lexile Band, then he or she should read texts either within his or her Lexile range, or within the appropriate Grade Level Lexile Band as outlined here. A Lexile measure is a good starting point for selecting books but should never be the only factor. The Summer Reading Assignment will be counted as three homework grades (one grade per book read) and will be due on August 23, 2019. Some titles are suggested below, or students may visit www.lexile.com to find their own books in their Lexile range. -

Iolanda Ramos Universidade Nova De Lisboa

A NOT SO SECRET GARDEN: ENGLISH ROSES, Iolanda Ramos VICTORIAN AESTHETICISM AND THE MAKING OF Universidade Nova de SOCIAL IDENTITIES Lisboa 1 Lady Lilith (1872), Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Delaware Art Museum 1 Iolanda Ramos is Assistant Professor at the FCSH-NOVA University of Lisbon, where she has been teaching since 1985, and a researcher at the Centre for English, Translation and Anglo-Portuguese Studies (CETAPS). She has published eXtensively on Victorian Studies and Neo-Victorianism within the framework of Utopian Studies as well as on intercultural, visual and gender issues. Her most recent publications include Performing Identities and Utopias of Belonging (co-edited with Teresa Botelho, Newcastle upon Tyne: CSP, 2013) and Matrizes Culturais: Notas para um Estudo da Era Vitoriana (Lisboa: Edições Colibri, 2014). GAUDIUM SCIENDI, Número 8, Julho 2015 98 A NOT SO SECRET GARDEN: ENGLISH ROSES, Iolanda Ramos VICTORIAN AESTHETICISM AND THE MAKING OF Universidade Nova de SOCIAL IDENTITIES Lisboa his essay seeks to draw on theories of representation so as to link the multi- signifying dimension of the garden with the language of flowers as T conveying a social and moral code, acknowledged both in the Victorian age and today, and therefore ultimately aims to revisit the making of social identities. It begins by placing the English rose within the tradition of British national symbols and proceeds to highlight how floral symbolism was widely used in the arts, focusing on a selection of Pre- Raphaelite paintings in order to show how floral imagery both sustained and subverted stereotyped female roles. It goes on to argue that floral representations were used as a means for women to recognise their "natural" place in society. -

Sacro E Profano (Filth and Wisdom)

NANNI MORETTI presenta SACRO E PROFANO (FILTH AND WISDOM) un film di MADONNA USCITA 12 GIUGNO 2009 Ufficio stampa: Valentina Guidi tel. 335.6887778 – [email protected] Mario Locurcio tel. 335.8383364 – [email protected] www.guidilocurcio.it SACRO E PROFANO (Filth and Wisdom) Un film di Madonna Scritto da Madonna & Dan Cadan Produttore esecutivo Madonna Prodotto da Nicola Doring Produttore associato Angela Becker Fotografia Tim Maurice Jones Montaggio Russell Icke Scene Gideon Ponte Costumi B. PERSONAGGI E INTERPRETI A.K. Eugene Hutz Holly Holly Weston Juliette Vicky McClure Professor Flynn Richard E. Grant Sardeep Inder Manocha Uomo d'affari Elliot Levey Francine Francesca Kingdon Chloe Clare Wilkie Harry Beechman Stephen Graham Moglie dell'uomo d'affari Hannah Walters Moglie di Sardeep Shobu Kapoor DJ Ade Lorcan O’Niell Guy Henry Nunzio Nunzio Palmara Mr Frisk Tim Wallers Padre di A.K. Olegar Fedorov Giovane A.K. Luca Surguladze Mikey Steve Allen Durata: 80’ I materiali stampa sono disponibili sul sito www.guidilocurcio.it 2 SACRO E PROFANO (Filth and Wisdom) SINOSSI A.K. (Eugene Hutz) è un musicista costretto a soddisfare i fantasmi sadomaso dei suoi clienti per poter finanziare le prove del suo gruppo punk-gitano. Juliette (Vicky McClure) lavora in farmacia ma sogna di fare la volontaria in Africa. Holly (Holly Weston) è una ballerina classica che, per pagare l'affitto, inizia una carriera inaspettatamente brillante come lap dancer. Attorno a loro una Londra colorata, multietnica, abitata da personaggi folkloristici. Un film eccentrico, ironico, che racconta storie uniche e universali attraverso la vita quotidiana - buffa, a volte tragica, ma sempre terribilmente autentica - dei suoi protagonisti. -

Casey Gallagher, BRAVE Coordinator Beth Brill, BRAVE Coordinator

Date: October 10, 2008 Re: Phase I Research and Development Grant for 2008-2009 Authors: Casey Gallagher, BRAVE Coordinator Beth Brill, BRAVE Coordinator Title: Using Children’s Picture Books to Promote SEL Using Children’s Books in the Classroom in Order to Promote SEL Themes In order to promote the social and emotional well-being of all students, and to strengthen a sensitive and caring community of learners within our middle school, this research and development grant demonstrates how children’s picture books can be used to promote teaching tolerance and acting morally. Lesson plans for various children’s picture books address specific SEL themes such as developing empathy, appreciating diversity, working cooperatively with others, bystander responsibility, viewing situations through various perspectives, and avoiding stereotyping and prejudging others. The ten enclosed lesson plans address the following ELA Standards as well in the following areas: Standard 1 • Students will use knowledge generated from texts to discover relationships and interpret information. Standard 2 • Students will read and listen to develop an understanding of the diverse social and cultural dimensions the texts represent. Standard 3 • As speakers and writers, students will form a variety of perspectives, their opinions and judgments on experiences, ideas, information, and issues. Standard 4 • Students will use oral and written language for effective social communication to enrich their understanding of people and their views. Lastly, this grant offers a method to utilize the BRAVE Student Ambassadors as peer-instructors. All BRAVE Student Ambassador-led lessons could be adapted for elementary age students as well to be used during an elementary school visitation.