Zen Sesshin with Kobun Chino Sensei

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Still Mind at 20 Years: a Personal Reflection GATE

March 2014 Vol.10 No. 1 in a one-room zendo in Jersey City. So I invited folks from a series of meditation sessions that Roshi had led at a church in Manhattan, as well as people I was seeing in my spiritual direction work who were interested in meditation. We called ourselves Greenwich Village Zen Community (GVZC) and Sensei Kennedy became our first teacher. We sat on chairs or, in some cases, on toss pillows that were strewn on the comfortable library sofa; there was no altar, no daisan, only two periods of sitting with kin-hin in between, along with some basic instruction. My major . enduring memory is that on most Tuesdays as we began Still sitting at 7 pm, the chapel organist would begin his weekly practice. The organ was on the other side of the library wall so our sitting space was usually filled with Bach & Co. Having come to Zen to “be in silence,” it drove me rather crazy. Still Mind at 20 Years: I didn’t have to worry too much, though, because after a few months the staff told us the library was no longer available. So we moved, literally down the street, to the A Personal Reflection (cont. on pg 2) by Sensei Janet Jiryu Abels Still Mind Zendo was founded on a selfish act. I needed a sangha to support my solo practice and, since none existed, I formed one. Now, 20 years later, how grateful I am that enough people wanted to come practice with each other back then, for this same sangha has proved to be the very rock of my continuing awakening. -

Full Diss Reformatted II

“NEWS THAT STAYS NEWS”: TRANSFORMATIONS OF LITERATURE, GOSSIP, AND COMMUNITY IN MODERNITY Lindsay Rebecca Starck A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Gregory Flaxman Erin Carlston Eric Downing Andrew Perrin Pamela Cooper © 2016 Lindsay Rebecca Starck ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Lindsay Rebecca Starck: “News that stays news”: Transformations of Literature, Gossip, and Community in Modernity (Under the direction of Gregory Flaxman and Erin Carlston) Recent decades have demonstrated a renewed interest in gossip research from scholars in psychology, sociology, and anthropology who argue that gossip—despite its popular reputation as trivial, superficial “women’s talk”—actually serves crucial social and political functions such as establishing codes of conduct and managing reputations. My dissertation draws from and builds upon this contemporary interdisciplinary scholarship by demonstrating how the modernists incorporated and transformed the popular gossip of mass culture into literature, imbuing it with a new power and purpose. The foundational assumption of my dissertation is that as the nature of community changed at the turn of the twentieth century, so too did gossip. Although usually considered to be a socially conservative force that serves to keep social outliers in line, I argue that modernist writers transformed gossip into a potent, revolutionary tool with which modern individuals could advance and promote the progressive ideologies of social, political, and artistic movements. Ultimately, the gossip of key American expatriates (Henry James, Djuna Barnes, Janet Flanner, and Ezra Pound) became a mode of exchanging and redefining creative and critical values for the artists and critics who would follow them. -

Primary Point, Vol 5 Num 3

I 'I Non Profit Org. �I 'I U.S. Postage /I J PAID 1 Address Correction Requested i Permit #278 ,:i Return Postage Guaranteed Providence, RI 'I Ii ARY OINT PUBLISHED BY THE KWAN UM ZENSCHOOL K.B.C. Hong Poep Won VOLUME FIVE, NUMBER THREE 528 POUND ROAD, CUMBERLAND, RI 02864 (401)658-1476 NOVEMBER 1988 PERCEIVE UNIVERSAL SOUND An Interview with Zen Master Seung Sahn. we are centered we can control our This interview with Zen Master Seung Sahn strongly and thus our condition and situation. appeared in "The American Theosophist" feelings, (AT) in May 1985. It is reprinted by permis AT: When you refer to a "center" do you sion of the Theosophical Society in America, mean any particular point in the body? Wheaton, Illinois. The interviewer is Gary DSSN: No, it is not just one point. To be Doore. Zen Master Sahn is now ,I Seung strongly centered is to be at one with the to his students as Dae Soen Sa referred by universal center, which means infinite time Nim. (See note on 3) page and infinite space. Doore: What is Zen Gary chanting? The first time one tries chanting medita Seung Sahn (Dae Soen Sa Nim): Chanting is tion there will be much confused thinking, very important in our practice. We call it many likes, dislikes and so on. This indicates "chanting meditation." Meditation means keep that the whole mind is outwardly-oriented. ing a not-moving mind. The important thing in Therefore, it is necessary first to return to chanting meditation is to perceive the sound of one's energy source, to return to a single point. -

Omori Sogen the Art of a Zen Master

Omori Sogen The Art of a Zen Master Omori Roshi and the ogane (large temple bell) at Daihonzan Chozen-ji, Honolulu, 1982. Omori Sogen The Art of a Zen Master Hosokawa Dogen First published in 1999 by Kegan Paul International This edition first published in 2011 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © The Institute of Zen Studies 1999 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 10: 0–7103–0588–5 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978–0–7103–0588–6 (hbk) Publisher’s Note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace. Dedicated to my parents Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Part I - The Life of Omori Sogen Chapter 1 Shugyo: 1904–1934 Chapter 2 Renma: 1934–1945 Chapter 3 Gogo no Shugyo: 1945–1994 Part II - The Three Ways Chapter 4 Zen and Budo Chapter 5 Practical Zen Chapter 6 Teisho: The World of the Absolute Present Chapter 7 Zen and the Fine Arts Appendices Books by Omori Sogen Endnotes Index Acknowledgments Many people helped me to write this book, and I would like to thank them all. -

Zen Masters at Play and on Play: a Take on Koans and Koan Practice

ZEN MASTERS AT PLAY AND ON PLAY: A TAKE ON KOANS AND KOAN PRACTICE A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brian Peshek August, 2009 Thesis written by Brian Peshek B.Music, University of Cincinnati, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Jeffrey Wattles, Advisor David Odell-Scott, Chair, Department of Philosophy John R.D. Stalvey, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Chapter 1. Introduction and the Question “What is Play?” 1 Chapter 2. The Koan Tradition and Koan Training 14 Chapter 3. Zen Masters At Play in the Koan Tradition 21 Chapter 4. Zen Doctrine 36 Chapter 5. Zen Masters On Play 45 Note on the Layout of Appendixes 79 APPENDIX 1. Seventy-fourth Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 80 “Jinniu’s Rice Pail” APPENDIX 2. Ninty-third Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 85 “Daguang Does a Dance” BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are times in one’s life when it is appropriate to make one’s gratitude explicit. Sometimes this task is made difficult not by lack of gratitude nor lack of reason for it. Rather, we are occasionally fortunate enough to have more gratitude than words can contain. Such is the case when I consider the contributions of my advisor, Jeffrey Wattles, who went far beyond his obligations in the preparation of this document. From the beginning, his nurturing presence has fueled the process of exploration, allowing me to follow my truth, rather than persuading me to support his. -

WW July August.Pub

Water Wheel Being one with all Buddhas, I turn the water wheel of compassion. —Gate of Sweet Nectar Zen Center of Los Angeles JULY / AUGUST 2011 Great Dragon Mountain / Buddha Essence Temple 2553 Buddhist Era Vol. 12 No. 4 Abiding Nowhere By Sensei Merle Kodo Boyd Book of Serenity, Case 75 Zuigan’s Permanent Principle Preface Even though you try to call it thus, it quickly changes. At the place where knowledge fails to reach, it should not be talked about. Here: is there something to penetrate? Main Case Attention! Zuigan asked Ganto, “What is the fundamental constant “Before we can say anything true about principle?” ourselves, we have changed. “ Ganto replied, “Moving.” Zuigan asked, “When moving, what then?” Ganto said, “You don’t see the fundamental constant The preface of this koan is clear. With wisdom and principle.” compassion, it points us in the direction of things as they Zuigan stood there thinking. are. Even as we perceive a thing, it changes. As we create Ganto remarked, “If you agree, you are not free of sense a name for what is, it is changing. As we use one word, and matter; if you don’t agree, you’ll be forever sunk in another is needed. This preface describes our human con- birth and death.” dition. An effort to settle in certainty will meet frustration and disappointment. Before we can say anything true Appreciatory Verse about ourselves, we have changed. What we say is only The round pearl has no hollows, partially true at best. The great raw gem isn’t polished. -

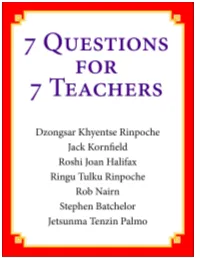

7 Questions for 7 Teachers

7 Questions for 7 Teachers On the adaptation of Buddhism to the West and beyond. Seven Buddhist teachers from around the world were asked seven questions on the challenges that Buddhism faces, with its origins in different Asian countries, in being more accessible to the West and beyond. Read their responses. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Jack Kornfield, Roshi Joan Halifax, Ringu Tulku Rinpoche, Rob Nairn, Stephen Batchelor, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo Introductory note This book started because I was beginning to question the effectiveness of the Buddhism I was practising. I had been following the advice of my teachers dutifully and trying to find my way, and actually not a lot was happening. I was reluctantly coming to the conclusion that Buddhism as I encountered it might not be serving me well. While my exposure was mainly through Tibetan Buddhism, a few hours on the internet revealed that questions around the appropriateness of traditional eastern approaches has been an issue for Westerners in all Buddhist traditions, and debates around this topic have been ongoing for at least the past two decades – most proactively in North America. Yet it seemed that in many places little had changed. While I still had deep respect for the fundamental beauty and validity of Buddhism, it just didn’t seem formulated in a way that could help me – a person with a family, job, car, and mortgage – very effectively. And it seemed that this experience was fairly widespread. My exposure to other practitioners strengthened my concerns because any sort of substantial settling of the mind mostly just wasn’t happening. -

Zenshinkan-Student-Handbook.Pdf

Zenshinkan Center for Japanese Martial, Spiritual,and Cultural Arts Student Handbook ZENSHINKAN DOJO STUDENT HANDBOOK CONTENTS The Way of Transformation .............................................................................................................. 2 Welcome to Zenshinkan Dojo ........................................................................................................... 3 Rules During Practice, Composed by the Founder ........................................................................... 5 Shugyo Policy .................................................................................................................................... 6 Basic Dojo Etiquette .......................................................................................................................... 7 Helpful Words and Phrases .............................................................................................................. 12 A History of Aikido ............................................................................................................................ 15 Zen Training ...................................................................................................................................... 17 For more information On: Our Lineage Test Requirements, Information and Applications Programs, Class Schedules and Upcoming Events Weapons Forms Techniques Zen Training Our website is a rich resource for our dojo’s current activities as well as our history. We also welcome and encourage your -

Adrian Belew Power Trio

This pdf was last updated: Dec/29/2010. Adrian Belew Power Trio King Crimson and Frank Zappa, David Bowie and Paul Simon, Talking Heads and Nine Inch Nails - Adrian Belew is well-known for his diverse travels around the musical map. Line-up Adrian Belew - guitar, vocals Julie Slick - bass Eric Slick - drums Andre Cholmondeley - tour manager/tech Plus one additional sound/tech manager On Stage: 3 Travel Party: 5 Website www.adrianbelew.net Biography Since 2006, Adrian Belew has led his favorite 'Power Trio' lineup, featuring Eric Slick on drums and Julie Slick on bass. They have been devastating audiences all around the USA and globally, from Italy to Canada to Germany to Japan. With the release of their brand- new CD 'Side Four - Live' they return to the road to stretch out the new material and introduce it to new audiences. The show will feature material from the new CD, classics from Adrian's many solo albums (including the recent 'Side One', 'SideTwo', and 'Side Three'), as well as solo moments, spirited improvisation and King Crimson compositions. 'Side One' features special guests Les Claypool of Primus and Danny Carey of Tool, and includes the Grammy-Nominated single - 'Beat Box Guitar'. The recently released 'Side Four (Live)' captures the current trio in a burning performance. Adrian is well-known for his diverse travels around the musical map - he first appeared on guitar-world radar when he joined Frank Zappa's band in 1977 for tours of the USA and Europe. When Frank Zappa hires you as his guitarist, people listen up. -

Tesi Del Dott. Jacopo Conti: Minimalismo ... -.:: Franco Fabbri

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI TORINO FACOLTÀ DI SCIENZE DELLA FORMAZIONE CORSO DI STUDIO TRIENNALE IN D.A.M.S. DISSERTAZIONE FINALE Minimalismo, modalità e improvvisazione nella musica dei nuovi King Crimson Relatore: Candidato: Ernesto Napolitano Jacopo Conti matr. n° 259083 Anno accademico 2006 - 2007 A mia zia, che credeva in me e mi ha sempre sostenuto. 1 PREMESSA “King Crimson was more a revolving door than a band. ” - Robert Palmer La cronologia dei King Crimson (KC) dal 1969 al 2003 è assai articolata, e include vari stili e molti musicisti con una sola presenza fissa, quella di Robert Fripp (1946), chitarrista e compositore inglese fondatore del gruppo. Considerati tra i fondatori del progressive rock, pubblicano l’album In The Court Of The Crimson King 1 nel 1969 con Fripp alla chitarra, Ian McDonald (1946) al sax e al mellotron, Michael Giles (1942) alla batteria, Greg Lake (1948) al basso e alla voce e Peter Sinfield (1943) nel ruolo di paroliere. I lunghi brani strutturati, gli elaborati riff suonati all’unisono e i testi di ispirazione fantastica e fiabesca non solo diventano la caratteristica principale del gruppo, ma anche gli elementi fondanti del nuovo genere. Già con il secondo lp, In The Wake Of Poseidon (1970), la formazione viene rimodellata: Mel Collins (1947) prende il posto di McDonald al sax, Gordon Haskell canta in alcuni brani (durante la lavorazione del disco Greg Lake abbandona il gruppo per andare a costituire il trio Emerson, Lake & Palmer), si aggiunge al pianoforte Keith Tippett (1947). Il gruppo si scioglie per qualche mese dopo l’incisione del disco per poi tornare, con un’altra formazione, alla fine del 1970. -

Lonely Sounds: Recorded Popular Music and American Society, 1949-1979

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History History, Department of 4-18-2008 Lonely Sounds: Recorded Popular Music and American Society, 1949-1979 Chris R. Rasmussen University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the History Commons Rasmussen, Chris R., "Lonely Sounds: Recorded Popular Music and American Society, 1949-1979" (2008). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 16. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Lonely Sounds: Popular Recorded Music and American Society, 1949-1979 by Christopher Rasmussen A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor Benjamin G. Rader Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2008 ii LONELY SOUNDS: POPULAR RECORDED MUSIC AND AMERICAN SOCIETY, 1949- 1979 Christopher Rasmussen, Ph.D. University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2008 Adviser: Benjamin G. Rader Lonely Sounds: Popular Recorded Music and American Society, 1949-1979 examines the relationship between the experience of listening to popular music and social disengagement. It finds that technological innovations, the growth of a youth culture, and market forces in the post- World War II era came together to transform the normal musical experience from a social event grounded in live performance into a consumable recorded commodity that satisfied individual desires. -

Prajñatara: Bodhidharma's Master

Summer 2008 Volume 16, Number 2 Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women TABLE OF CONTENTS Women Acquiring the Essence Buddhist Women Ancestors: Hymn to the Perfection of Wisdom Female Founders of Tibetan Buddhist Practices Invocation to the Great Wise Women The Wonderful Benefits of a H. H. the 14th Dalai Lama and Speakers at the First International Congress on Buddhist Women’s Role in the Sangha Female Lineage Invocation WOMEN ACQUIRING THE ESSENCE An Ordinary and Sincere Amitbha Reciter: Ms. Jin-Mei Roshi Wendy Egyoku Nakao Chen-Lai On July 10, 1998, I invited the women of our Sangha to gather to explore the practice and lineage of women. Prajñatara: Bodhidharma’s Here are a few thoughts that helped get us started. Master Several years ago while I was visiting ZCLA [Zen Center of Los Angeles], Nyogen Sensei asked In Memory of Bhiksuni Tian Yi (1924-1980) of Taiwan me to give a talk about my experiences as a woman in practice. I had never talked about this before. During the talk, a young woman in the zendo began to cry. Every now and then I would glance her One Worldwide Nettwork: way and wonder what was happening: Had she lost a child? Ended a relationship? She cried and A Report cried. I wondered what was triggering these unstoppable tears? The following day Nyogen Sensei mentioned to me that she was still crying, and he had gently Newsline asked her if she could tell him why. “It just had not occurred to me,” she said, “that a woman could be a Buddha.” A few years later when I met her again, the emotions of that moment suddenly surfaced.