000-2012-18Th 목차 국제세미나 논문집.Hwp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adriaan Reland and Dutch Scholarship on Islam Scholarly and Religious Visions of the Muslim Pilgrimage

chapter 4 Adriaan Reland and Dutch Scholarship on Islam Scholarly and Religious Visions of the Muslim Pilgrimage Richard van Leeuwen The development of Dutch Oriental studies and the study of Islam was from the beginning of the seventeenth century connected with the religious debates between the Catholic Church in Rome and the various Protestant communi- ties in northern Europe. The Protestant scholars subverted the monopoly held by the Vatican on the study of Islam and its polemics against the ‘false’ faith, which was often based on incorrect presuppositions. Debates about Islam became rapidly entangled with opinions about religion in general or about Catholic doctrines and practices more specifically. In their anti-Catholic attitude the Protestant scholars even harboured some sympathy for certain aspects of Islam, although they emphasised that Muhammad should not be considered an authentic prophet. They argued for a more objective examina- tion of Islam, to be able to counter the rivalling faith more effectively. This tendency can be clearly observed in publications about Islam in the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. One may argue that the Protestant trend in Oriental studies culminated in Adriaan Reland’s famous compendium of Islamic doctrines De religione Mohammedica, which was published in 1705 and was subsequently translated into various languages. The second edition of the book, published in 1717, which was based on authentic Arabic manuscript sources, not only contained a con- cise but detailed survey of the main tenets and practices of Islam, but was also supplemented with a section in which the main European misperceptions of Islam were corrected. -

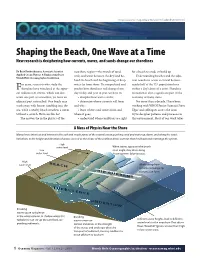

Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New Research Is Deciphering How Currents, Waves, and Sands Change Our Shorelines

http://oceanusmag.whoi.edu/v43n1/raubenheimer.html Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New research is deciphering how currents, waves, and sands change our shorelines By Britt Raubenheimer, Associate Scientist nearshore region—the stretch of sand, for a beach to erode or build up. Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Dept. rock, and water between the dry land be- Understanding beaches and the adja- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hind the beach and the beginning of deep cent nearshore ocean is critical because or years, scientists who study the water far from shore. To comprehend and nearly half of the U.S. population lives Fshoreline have wondered at the appar- predict how shorelines will change from within a day’s drive of a coast. Shoreline ent fickleness of storms, which can dev- day to day and year to year, we have to: recreation is also a significant part of the astate one part of a coastline, yet leave an • decipher how waves evolve; economy of many states. adjacent part untouched. One beach may • determine where currents will form For more than a decade, I have been wash away, with houses tumbling into the and why; working with WHOI Senior Scientist Steve sea, while a nearby beach weathers a storm • learn where sand comes from and Elgar and colleagues across the coun- without a scratch. How can this be? where it goes; try to decipher patterns and processes in The answers lie in the physics of the • understand when conditions are right this environment. Most of our work takes A Mess of Physics Near the Shore Many forces intersect and interact in the surf and swash zones of the coastal ocean, pushing sand and water up, down, and along the coast. -

Secondment Plan

Secondment Plan Capacity Building in Asia for Resilience Education Project (CABARET) WP6 De La Salle University Environmental Hydraulics Institute of the University of Cantabria (IHC) 2017-2020 LIST OF ACRONYMS ADPC - Asian Disaster Preparedness Center CABARET - Capacity Building in Asia for Resilience Education CCA - Climate Change Adaptation DRRM - Disaster Risk Reduction and Management EU - European Union FSLGA - Federation of Sri Lankan Local Government Authorities HEI - Higher Education Institution IHC - Environmental Hydraulics Institute of the University of Cantabria IOC/UNESCO - Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization MHEWS - Multi-Hazard Early Warning System MOA - Memorandum of Agreement MOU - Memorandum of Understanding SEA - Socio-Economic Actors Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVE .......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Rationale ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Objective ....................................................................................................................................... 2 2 METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................................................... 2 3 PARTNERSHIP STRATEGY AT THE REGIONAL LEVEL ............................................................................. -

I After Conversion

i After Conversion © García-Arenal, 2016 | doi 10.1163/9789004324329_001 This is an open access chapter distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC-ND License. Mercedes García-Arenal - 978-90-04-32432-9 Downloaded from Brill.com06/07/2019 07:07:11PM via Library of Congress ii Catholic Christendom, 1300–1700 Series Editors Giorgio Caravale, Roma Tre University Ralph Keen, University of Illinois at Chicago J. Christopher Warner, Le Moyne College, Syracuse The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cac Mercedes García-Arenal - 978-90-04-32432-9 Downloaded from Brill.com06/07/2019 07:07:11PM via Library of Congress iii After Conversion Iberia and the Emergence of Modernity Edited by Mercedes García-Arenal LEIDEN | BOSTON Mercedes García-Arenal - 978-90-04-32432-9 Downloaded from Brill.com06/07/2019 07:07:11PM via Library of Congress iv This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC-ND License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/ Want or need Open Access? Brill Open offers you the choice to make your research freely accessible online in exchange for a publication charge. Review your various options on brill.com/brill-open. Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 2468-4279 isbn 978-90-04-32431-2 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-32432-9 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by the Editor and the Authors. -

Beachcombers Field Guide

Beachcombers Field Guide The Beachcombers Field Guide has been made possible through funding from Coastwest and the Western Australian Planning Commission, and the Department of Fisheries, Government of Western Australia. The project would not have been possible without our community partners – Friends of Marmion Marine Park and Padbury Senior High School. Special thanks to Sue Morrison, Jane Fromont, Andrew Hosie and Shirley Slack- Smith from the Western Australian Museum and John Huisman for editing the fi eld guide. FRIENDS OF Acknowledgements The Beachcombers Field Guide is an easy to use identifi cation tool that describes some of the more common items you may fi nd while beachcombing. For easy reference, items are split into four simple groups: • Chordates (mainly vertebrates – animals with a backbone); • Invertebrates (animals without a backbone); • Seagrasses and algae; and • Unusual fi nds! Chordates and invertebrates are then split into their relevant phylum and class. PhylaPerth include:Beachcomber Field Guide • Chordata (e.g. fi sh) • Porifera (sponges) • Bryozoa (e.g. lace corals) • Mollusca (e.g. snails) • Cnidaria (e.g. sea jellies) • Arthropoda (e.g. crabs) • Annelida (e.g. tube worms) • Echinodermata (e.g. sea stars) Beachcombing Basics • Wear sun protective clothing, including a hat and sunscreen. • Take a bottle of water – it can get hot out in the sun! • Take a hand lens or magnifying glass for closer inspection. • Be careful when picking items up – you never know what could be hiding inside, or what might sting you! • Help the environment and take any rubbish safely home with you – recycle or place it in the bin. Perth• Take Beachcomber your camera Fieldto help Guide you to capture memories of your fi nds. -

The Manuscript Collection of Adriaan Reland in the University Library of Utrecht and Beyond

Chapter 11 The Manuscript Collection of Adriaan Reland in the University Library of Utrecht and Beyond Bart Jaski When on 4 November 1700 Adriaan Reland (1676–1718) was appointed as pro- fessor of Oriental languages at the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Utrecht, this was something of a break with the past. In effect, he succeeded Johannes Leusden, who had taught the sacred languages at the Faculty of Theology from 1650 until his death in 1699, and had published widely on Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic and Syriac in relation to biblical texts. Leusden had been a faithful pupil of the strict Calvinist theologian Gijsbert Voet (Voetius), who from the foundation of the university in 1636 until his death in 1676 had dominated the Faculty of Theology, and indeed the university itself. Reland had studied in Utrecht, among others Hebrew under Leusden, but had a different outlook on the relationship between theology and philosophy than his teacher, as his dissertation of 1694 already shows.1 He had acquired an interest in the Arabic language, stimulated by his fellow student Heinrich Sike (Sikius), who had come from Bremen to study in Leiden and later worked in Utrecht.2 In subsequent disputations and in his oration of 1701 Reland would argue for the use of the knowledge of Oriental languages—in particular Arabic and Persian—for the study of Christian theology and its defence against Islam.3 He names those who had already reaped the fruits of this study, includ- ing Joseph Justus Scaliger (1540–1609), Thomas Erpenius (1584–1624), Jacobus Golius (1596–1667), who had all lectured in Leiden, and Johann Heinrich Hottinger (1620–1667), who died before he could do so.4 1 Reland, Disputatio philosophica inauguralis, De libertate philosophandi (1694); see further Van Amersfoort, Liever Turks dan Paaps?, pp. -

)22' 6(&85,7< 5(6($5&+ 352-(&7

)22'6(&85,7<5(6($5&+352-(&7 RECOMMENDATIONS ON SAMPLE DESIGN FOR POST-HARVEST SURVEYS IN ZAMBIA BASED ON THE 2000 CENSUS By David J. Megill WORKING PAPER No. 11 FOOD SECURITY RESEARCH PROJECT LUSAKA, ZAMBIA February 2004 (Downloadable at: http://www.aec.msu.edu/agecon/fs2/zambia/index.htm ) RECOMMENDATIONS ON SAMPLE DESIGN FOR POST-HARVEST SURVEYS IN ZAMBIA BASED ON THE 2000 CENSUS David J. Megill FSRP Working Paper No. 11 February 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Food Security Research Project is a collaboration between the Agricultural Consultative Forum (ACF), the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries (MAFF), and Michigan State University’s Department of Agricultural Economics (MSU). We wish to acknowledge the financial and substantive support of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in Lusaka. Research support from the Global Bureau, Office Agriculture and Food Security, and the Africa Bureau, Office of Sustainable Development at USAID/Washington also made it possible for MSU researchers to contribute to this work. This study has been made possible thanks to the contributions of a number of people and organizations. In particular, the Agriculture and Environment Division, Central Statistical Office (CSO), and the Database Management Unit, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (MACO), who provided assistance in analyzing and utilizing 2000 Census data. MACO and CSO also actively participated in technical discussions that took place during the sample design process, providing the opportunity for the author, D.J. Megill (sampling consultant for FSRP), to refine the methodologies proposed in FSRP Working Paper No. 2 and present a working version of the new sampling methodology. -

Coastal Morphology Report Southwold to Benacre Denes (Suffolk)

Coastal Morphology Report Southwold to Benacre Denes (Suffolk) RP016/S/2010 March 2010 Title here in 8pt Arial (change text colour to black) i We are the Environment Agency. We protect and improve the environment and make it a better place for people and wildlife. We operate at the place where environmental change has its greatest impact on people’s lives. We reduce the risks to people and properties from flooding; make sure there is enough water for people and wildlife; protect and improve air, land and water quality and apply the environmental standards within which industry can operate. Acting to reduce climate change and helping people and wildlife adapt to its consequences are at the heart of all that we do. We cannot do this alone. We work closely with a wide range of partners including government, business, local authorities, other agencies, civil society groups and the communities we serve. Published by: Shoreline Management Group Environment Agency Kingfisher House, Goldhay Way Orton goldhay, Peterborough PE2 5ZR Email: [email protected] www.environment-agency.gov.uk © Environment Agency 2010 Further copies of this report are available from our publications catalogue: All rights reserved. This document may be http://publications.environment-agency.gov.uk reproduced with prior permission of or our National Customer Contact Centre: T: the Environment Agency. 03708 506506 Email: [email protected]. ii Cliffs at Eastern Bavents Photo: Environment Agency Glossary Accretion The accumulation of sediment -

Seychelles Coastal Management Plan 2019–2024 Mahé Island, Seychelles

Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change Seychelles Coastal Management Plan 2019–2024 Mahé Island, Seychelles. Photo: 35007 Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change Seychelles Coastal Management Plan 2019–2024 © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with the Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change of Seychelles. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors or the governments they represent, and the European Union. In addition, the European Union is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denomina- tions, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. -

Changing Indonesian Sea Names Ferjan Ormeling Utrecht University

Changing Indonesian Sea Names Ferjan Ormeling Utrecht University Introduction Foreign influence on Indonesian toponymy is negligible. Names that are demonstra- bly of foreign origin are only a handful. Examples are the names Flores, Enggano and Rondo, which are of Portuguese origin; some names of mountain ranges in the interior of Borneo still show the influence of German explorers. The names of two prominent cities, Batavia and Buitenzorg, were decolonised and changed into Jakarta and Bogor (Batavia referred to the Batavi, a Germanic tribe living in the Netherlands in Roman times; Buitenzorg is the Dutch equivalent of the French name Sanssoucis). But, overall, the namescape in Indonesia is an Indonesian one. Underneath the layer of Indonesian names, however, there are still foreign influences, masked because they have been translated into Bahasa Indonesia (the Indonesian language), or because Indonesian names were used by foreigners. As far as I have been able to assess there was no indigenous tradition in naming specific water bodies, apart from the South Sea (Samudra Kidul or Laut Kidul) and the naming of Indonesian seas thus was due to foreign or colonial intervention. Sources My sources in finding out the chronology of this sea naming process have been maps and charts, geographical descriptions and pilots or nautical guides as available through Google Books. No Indonesian literature could be found on the subject. I have studied old printed maps of Southeast Asia, in order to find out when specific names were first used, and also manuscript maps: a recent source (2010) is the book Sailing for the East, by Schilder and Kok from the Explokart Research Group at Utrecht University, which presents an overview of all the manuscript charts on vellum produced for the Dutch East India Company (VOC). -

Tool for the Identification and Assessment Of

Ocean & Coastal Management 113 (2015) 8e17 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ocean & Coastal Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ocecoaman Tool for the identification and assessment of Environmental Aspects in Ports (TEAP) * Martí Puig a, Chris Wooldridge b, Joaquim Casal a, Rosa Mari Darbra c, a Center for Technological Risk Studies (CERTEC), Department of Chemical Engineering, Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya · BarcelonaTech, Diagonal 647, 08028 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain b School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Main Building, Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3AT, United Kingdom c Group on Techniques for Separating and Treating Industrial Waste (SETRI), Department of Chemical Engineering, Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya · BarcelonaTech, Diagonal 647, 08028 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain article info abstract Article history: A new tool to assist port authorities in identifying aspects and in assessing their significance (TEAP) has Received 23 January 2015 been developed. The present research demonstrates that although there is a high percentage of European Received in revised form ports that have already identified their Significant Environmental Aspects (SEA), most of these ports do 26 March 2015 not use any standardized method. This suggests that some of the procedures used may not necessarily be Accepted 7 May 2015 science-based, systematic in approach or appropriate for the purpose of implementing effective envi- Available online 19 May 2015 ronmental management. For the port sector as a whole, where the free-exchange of environmental in- formation and experience is an established policy of the European Sea Ports Organization's (ESPO) and Keywords: Significant environmental aspects the EcoPorts Network, developing a tool to assist ports in identifying SEAs can be very useful. -

ROBINSON CRUSOE in NEDERLAND. EEN BIJDRAGE TOT DE GESCHIEDENIS VAN DEN ROMAN in DE Xviiie EEUW

p'- 3432 THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ,^. ROBINSON CRUSOE IN NEDERLAND. EEN BIJDRAGE TOT DE GESCHIEDENIS VAN DEN ROMAN IN DE XVIIIe EEUW. I ROBINSON CRUSOE IN NEDERLAND. EEN BIJDRAGE TOT DE GESCHIEDENIS VAN DEN ROMAN IN DE XVIIP EEUW. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRUGING VAN DEN GRAAD VAN DOCTOR IN DE NEDERLANDSCHE LET- TERKUNDE AAN DE RIJKS-UNIVERSITEIT TE GRONINGEN, OP GEZAG VAN DEN RECTOR MAGNIFICUS Mr. P. PET, HOOGLEERAAR IN DE FACULTEIT DER RECHTSGELEERD- HEID, TEGEN DE BEDENKINGEN VAN DE FACULTEIT IN HET OPENBAAR TE VERDEDIGEN OP ZATERDAG 15 JUNI 1907, DES NAMIDDAGS TE 3 UUR DOOR WERNER HENDRIK STAVERMAN, GEBOREN TE TWELLO. M. DE WAAL. — 1907. — GRONINGEN. ' .•'^ AAN MUX OUDEKS. 6S8952 Mijn akademische loopbaan mag ik niet eindigen, zonder een ivoord van dank te richten tot mijn Hooggeachten Promotor, Professor Van Helten, iviens lessen ik soovele jaren lieh mogen volgen, en die zich de niet geringe moeite heeft getroost, mijn in het sclirijven van een disser- tatie zoo ongeoefende hand te leiden. De Professoren Symons, Ivern, Heymans, Huizinga en de Heer Pol, en de Professoren Bussemaker en Speyer, tvier colleges ik voor him vertrek naar elders heb gevolgd, mogen zich over- tuigd hoiide7i, dat ik him lessen en raadgevingen steeds ten hoogste zal hlijven loaardeeren. Professor Van Hamel mijn erkentelijkheid te betuigen, is mii niet meer vergimd. Aan Dr. Kronenberg te Deventer, die een ivakend oog Jieeft laten gaan over mijn proefschrift ; aan Dr. Ullrich te Brandenburg a. H., die den hem onbekenden buitenlander welioillend ontvangen en gaarne hem inlichtingen gegeven heeft; aan de besturen en beambten der bibliotheken in Gro- den Leiden en en vooral aan ningen, Haag , Amsterdam, Dr.