Changing Indonesian Sea Names Ferjan Ormeling Utrecht University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] [Southeast Asia] Stock#: 64430 Map Maker: Fries Date: 1535 Place: Vienna Color: Hand Colored Condition: VG Size: 17 x 12 inches Price: $ 1,200.00 Description: One of Ptolemy's Greatest Errors An important early map of the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia, drawn from Ptolemy's Geography. The map illustrates one of the greatest of the Ptolemy errors, the belief that a southern continent existed, which counter-balanced the weight of the land-masses in the northern hemisphere, to keep the earth stable on its axis. The present map illustrates a portion of the landlocked Indian Ocean, including much of the Indian Ocean (Indicum Mare), as it had been mapped by Ptolemy. As noted by Suarez: . .After crossing east of the Ganges (whose Delta is on the left), we enter Aurea region, a kingdom of gold, which is roughly located where Burma begins today. Above it lies Cirradia, from where, Ptolemy tells us, comes the finest cinnamon. Further down the coast one comes to Argentea Regio, a kingdom of silver, "in which there is said to be much well-guarded metal." Besyngiti, which is also said to have much gold, is situated close by. The region's inhabitants are reported to be "white, short, with flat noses." Here the Temala River, because of its position and because it empties through a southerly elbow of land, appears to be the Irrawaddy. If so, the Sinus Sabaricus would be the Gulf of Martaban, whose eastern shores begin the Malay Peninsula, and the Sinus Permimulicus would be the Gulf of Siam. -

Islam and Politics in Madura: Ulama and Other Local Leaders in Search of Influence (1990 – 2010)

Islam and Politics in Madura: Ulama and Other Local Leaders in Search of Influence (1990 – 2010) Islam and Politics in Madura: Ulama and Other Local Leaders in Search of Influence (1990 – 2010) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof.mr. C.J.J.M. Stolker, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op woensdag 28 augustus 2013 klokke 13.45 uur door Yanwar Pribadi geboren te Sukabumi in 1978 Promotiecommissie Promotor : Prof. dr. C. van Dijk Co-Promotor : Dr. N.J.G. Kaptein Overige Leden : Prof. dr. L.P.H.M. Buskens Prof. dr. D.E.F. Henley Dr. H.M.C. de Jonge Layout and cover design: Ade Jaya Suryani Contents Contents, ................................................................................ vii A note on the transliteration system, ..................................... xi List of tables and figures, ........................................................ xiii Acknowledgements, ................................................................ xv Maps, ....................................................................................... xviii Chapter 1 Introduction, .......................................................................... 1 Madura: an island of piety, tradition, and violence, .............. 1 Previous studies, ..................................................................... 3 Focus of the study, .................................................................. 9 Methods and sources, ............................................................ -

Fish Drying in Indonesia

The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. Its mandate is to help identify agri cultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing country researchers in fields where Australia has a special research competence. Where trade names are used this constitutes neither endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by the Centre. ACIAR PROCEEDINGS This series of publications includes the full proceedings of research workshops or symposia organised or supported by ACIAR. Numbers in this series are distributed internationally to selected individuals and scientific institutions. Recent numbers in the series are listed inside the back cover. © Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. GPO Box 1571, Canberra. ACT 2601 Champ. BR and Highley. E .• cd. 1995. Fish drying in Indonesia. Proceedings of an international workshop held at Jakarta. Indonesia. 9-10 February 1994. ACIAR Proceedings !'Io. 59. 106p. ISBN I 86320 144 0 Technical editing. typesetting and layout: Arawang Information Bureau Ply Ltd. Canberra. Australia. Fish Drying in Indonesia Proceedings of an international workshop held at Jakarta, Indonesia on 9-10 February 1994 Editors: B.R. Champ and E. Highley Sponsors: Agency for Agricultural Research and Development, Indonesia Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research Contents Opening Remarks 5 F. Kasryno Government Policy on Fishery Agribusiness Development 7 Ir. H. Muchtar Abdullah An Overview of Fisheries and Fish Proeessing in Indonesia 13 N. Naamin Problems Assoeiated with Dried Fish Agribusiness in Indonesia 18 Soegiyono Salted Fish Consumption in Indonesia: Status and Prospects 25 v.T. -

Delineation of Sedimentary Subbasin and Subsurface Interpretation East Java Basin in the Madura Strait and Surrounding Area Based on Gravity Data Analysis

Bulletin of the Marine Geology, Vol. 34, No. 1, June 2019, pp. 1 to 16 Delineation of Sedimentary Subbasin and Subsurface Interpretation East Java Basin in the Madura Strait and Surrounding Area Based on Gravity Data Analysis Delineasi Subcekungan Sedimen dan Interpretasi Bawah Permukaan Cekungan Jawa Timur Wilayah Selat Madura dan Sekitarnya Berdasarkan Analisis Data Gayaberat Imam Setiadi1, Budi Setyanta2, Tumpal B. Nainggolan1, Joni Widodo1 1 Marine Geological Institute, Jl. Dr. Djundjunan No. 236, Bandung, 40174, Indonesia. 2 Centre for Geological Survey, Jl.Diponegoro No.57. Bandung, 40122, Indonesia. Corresponding author: [email protected] (Received 08 January 2019; in revised form 15 January 2019 accepted 27 March 2019) ABSTRACT: East Java basin is a very large sedimentary basin and has been proven produce hydrocarbons, this basin consists of several different sub-basins, one of the sub-basin is in the Madura Strait and surrounding areas. Gravity is one of the geophysical methods that can be used to determine geological subsurface configurations and delineate sedimentary sub-basin based on density parameter. The purposes of this study are to delineate sedimentary sub-basins, estimate the thickness of sedimentary rock, interpret subsurface geological model and identify geological structures in the Madura Strait and surrounding areas. Data analysis which used in this paper are spectral analysis, spectral decomposition filter and 2D forward modeling. The results of the spectral analysis show that the thickness of sedimentary rock is about 3.15 Km. Spectral decomposition is performed at four different wave numbers cut off, namely (0.36, 0.18, 0.07 and 0.04), each showing anomaly patterns at depth (1 Km, 2 Km, 3 Km and 4 Km). -

Adriaan Reland and Dutch Scholarship on Islam Scholarly and Religious Visions of the Muslim Pilgrimage

chapter 4 Adriaan Reland and Dutch Scholarship on Islam Scholarly and Religious Visions of the Muslim Pilgrimage Richard van Leeuwen The development of Dutch Oriental studies and the study of Islam was from the beginning of the seventeenth century connected with the religious debates between the Catholic Church in Rome and the various Protestant communi- ties in northern Europe. The Protestant scholars subverted the monopoly held by the Vatican on the study of Islam and its polemics against the ‘false’ faith, which was often based on incorrect presuppositions. Debates about Islam became rapidly entangled with opinions about religion in general or about Catholic doctrines and practices more specifically. In their anti-Catholic attitude the Protestant scholars even harboured some sympathy for certain aspects of Islam, although they emphasised that Muhammad should not be considered an authentic prophet. They argued for a more objective examina- tion of Islam, to be able to counter the rivalling faith more effectively. This tendency can be clearly observed in publications about Islam in the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. One may argue that the Protestant trend in Oriental studies culminated in Adriaan Reland’s famous compendium of Islamic doctrines De religione Mohammedica, which was published in 1705 and was subsequently translated into various languages. The second edition of the book, published in 1717, which was based on authentic Arabic manuscript sources, not only contained a con- cise but detailed survey of the main tenets and practices of Islam, but was also supplemented with a section in which the main European misperceptions of Islam were corrected. -

Indonesia Weather Bulletin for Shipping

BADAN METEOROLOGI KLIMATOLOGI DAN GEOFISIKA STASIUN METEOROLOGI MARITIM KLAS I TANJUNG PRIOK Jln. Padamarang no. 4A Pelabuhan Tanjung Priok Jakarta 14310 Telp. 43912041, 43901650, 4351366 Fax. 4351366 Email : [email protected] BMKG TANJUNG PRIOK, JUNE 16, 2015 INDONESIA WEATHER BULLETIN FOR SHIPPING I. PART ONE : NIL II. PART TWO : SYNOPTIC WEATHER ANALYSIS : FOR 00.00 UTC DATE JUNE 16, 2015 - GENERAL SITUATION WEAK TO MODERATE SOUTHEAST TO WEST WINDS. - INTER TROPICAL CONVERGENCE ZONE [ I.T.C.Z. ] PASSING OVER : NIL. - CONVERGENCE LINE (C.L.) PASSING OVER : SOUTH CHINA SEA, AND NORTH HALMAHERA PACIFIC OCEAN. - LOW PRESSURE AREA : NIL. III. PART THREE : SEA AREA FORECAST VALID 24 HOURS FROM : 10. 00 UTC DATE JUNE 16, 2015 AS FOLLOWS : A. WEATHER : 1. THE POSSIBILITY OF SCATTERED TO OVERCAST AND MODERATE RAIN OCCASIONALLY FOLLOWED BY THUNDERSTORM COULD OCCUR THE OVER AREAS OF : LHOKSEUMAWE WATERS, MALACA STRAIT, ANAMBAS- NATUNA ISLANDS WATERS, NATUNA SEA, RIAU ISLANDS WATERS, LINGGA ISLANDS WATERS, SINGKAWANG WATERS, TARAKAN WATERS, BALIKPAPAN WATERS, BITUNG-MANADO WATERS, SANGIHE-TALAUD ISLANDS WATERS, MALUKU SEA, HALMAHERA ISLANDS WATERS, HALMAHERA SEA, SULA ISLANDS WATERS, SORONG WATERS, CENDRAWASIH GULF, SARMI-JAYAPURA ISLANDS WATERS AND AMAMAPARE WATERS. 2. THE POSSIBILITY OF SCATTERED TO BROKEN CLOUDS AND RAIN OR LOCAL RAIN COULD OCCUR THE OVER AREAS OF : SIMEULUE-MEULABOH WATERS, SIBOLGA-NIAS ISLANDS WATERS, WEST SUMATRA AND MENTAWAI ISLANDS WATERS, BANGKA STRAIT, NORTH PANGKAL PINANG WATERS, KARIMATA STRAIT, PONTIANAK WATERS, KETAPANG WATERS, KOTABARU WATERS, MAKASAR STRAIT, NORTHERN SULAWESI ISLAND WATERS, TOMINI GULF, BANGGAI ISLANDS WATERS, SERAM SEA, MANOKWARI WATERS AND BIAK WATERS. B. WINDS DIRECTION AND SPEED FROM SURFACE UP TO 3000 FEET : WINDS OVER INDONESIA WATERS, NORTHERN EQUATOR GENERALLY SOUTHEAST TO SOUTHWEST AND SOUTHERN EQUATOR GENERALLY SOUTHEAST TO WEST AT ABOUT 3 TO 25 KNOTS. -

Supplied Through the Parthians) from the 1St Century BC, Even Though the Romans Thought Silk Was Obtained from Trees

Chinese Silk in the Roman Empire Trade with the Roman Empire followed soon, confirmed by the Roman craze for Chinese silk (supplied through the Parthians) from the 1st century BC, even though the Romans thought silk was obtained from trees: The Seres (Chinese), are famous for the woolen substance obtained from their forests; after a soaking in water they comb off the white down of the leaves... So manifold is the labor employed, and so distant is the region of the globe drawn upon, to enable the Roman maiden to flaunt transparent clothing in public. -(Pliny the Elder (23- 79, The Natural History) The Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds: the importation of Chinese silk caused a huge outflow of gold, and silk clothes were considered to be decadent and immoral: I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes... Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body. -(Seneca the Younger (c. 3 BCE- 65 CE, Declamations Vol. I) The Roman historian Florus also describes the visit of numerous envoys, included Seres (perhaps the Chinese), to the first Roman Emperor Augustus, who reigned between 27 BCE and 14 CE: Even the rest of the nations of the world which were not subject to the imperial sway were sensible of its grandeur, and looked with reverence to the Roman people, the great conqueror of nations. -

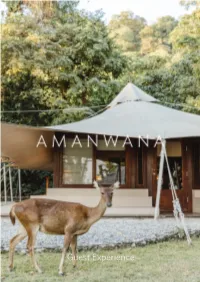

Guest Experience

Guest Experience Contents The Amanwana Experience 3 Spa & Wellness 29 During Your Stay 5 Amanwana Spa Facilities 29 A New Spa Language 30 Aman Signature Rituals 32 Amanwana Dive Centre 7 Nourishing 33 Grounding 34 Diving at Amanwana Bay 7 Purifying 35 Diving at the Outer Reefs 8 Body Treatments 37 Diving at Satonda Island 10 Massages 38 Night Diving 13 Courses & Certifications 14 Moyo Conservation Fund 41 At Sea & On Land 17 Island Conservation 41 Species Protection 42 Water Sports 17 Community Outreach & Excursions 18 Camp Responsibility 43 On the Beach 19 Trekking & Cycling 20 Amanwana Kids 45 Leisure Cruises & Charters 23 Little Adventurers 45 Leisure Cruises 23 Fishing 24 Charters 25 Dining Experiences 27 Memorable Moments 27 2 The Amanwana Experience Moyo Island is located approximately eight degrees south of the equator, within the regency of Nusa Tenggara Barat. The island has been a nature reserve since 1976 and measures forty kilometres by ten kilometres, with a total area of 36,000 hectares. Moyo’s highest point is 600 meters above the Flores Sea. The tropical climate provides a year-round temperature of 27-30°C and a consistent water temperature of around 28°C. There are two distinct seasons. The monsoon or wet season is from December to March and the dry season from April to November. The vegetation on the island ranges from savannah to dense jungle. The savannah land dominates the plateaus and the jungle the remaining areas. Many varieties of trees are found on the island, such as native teak, tamarind, fig, coral and banyan. -

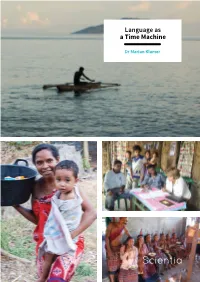

Language As a Time Machine

Language as a Time Machine Dr Marian Klamer LANGUAGE AS A TIME MACHINE Language is the primary tool used by human beings to communicate with each other, allowing them to co-operate, explore their similarities and sometimes even bridge their differences. Yet it can also become a means to dive deep into the past, acting as a time machine that helps to re-construct the history of geographical areas and the populations inhabiting them. Dr Marian Klamer at Leiden University specialises in the study of languages in their every aspect, with the aim of opening a window onto the past of areas of the world that have very few historical records. The ways in which human beings Dr Klamer spent her childhood in a small communicate have constantly evolved village in the jungle, inhabited by people throughout the years. Yet, regardless of from different clans. ‘Every clan had whether individuals communicate in person, their own language, so several Papuan or through phone, e-mail, text message or languages where spoken in the village, pigeon post, all verbal and written exchanges alongside Papuan Malay that was used as between them are made possible by the a lingua franca; at home we spoke Dutch. existence of languages. Perhaps because of this early multi-lingual environment I have always been curious Languages allow us to express complex about how people use languages, and how thoughts, abstract ideas and feelings to one different languages are structured,’ she says. another, which would be difficult to convey using mere gestures and arbitrary sounds. Her early fascination with languages Roughly 6,500 languages are spoken in prompted her to study linguistics later in the world today, but about a third of these life, specialising in Austronesian and Papuan have less than 1000 speakers. -

The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither

The Golden Chersonese and The Way Thither Isabella L. Bird (Mrs. Bishop) The Golden Chersonese and The Way Thither Table of Contents The Golden Chersonese and The Way Thither......................................................................................................1 Isabella L. Bird (Mrs. Bishop).......................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER.....................................................................................................................3 LETTER I....................................................................................................................................................13 LETTER II...................................................................................................................................................16 LETTER III..................................................................................................................................................18 LETTER IV..................................................................................................................................................22 LETTER IV (Continued).............................................................................................................................28 LETTER IV (Continued).............................................................................................................................33 -

Indonesia Cruise – Bali to Flores

Indonesia Cruise – Bali to Flores Trip Summary Immerse yourself in Bali, Komodo Island, and Indonesia's Lesser Sunda Islands from an intimate perspective, sailing through a panorama of islands and encountering new wonders on a daily basis. Explore crystalline bays, tribal villages, jungle-clad mountains, and mysterious lakes on this eight- day long Indonesian small-ship adventure. This exciting adventure runs from Flores to Bali or Bali to Flores depending on the week! (Please call your Adventure Consultant for more details). Itinerary Day 1: Arrive in Bali In the morning we will all meet at the Puri Santrian Hotel in South Bali before boarding our minibus for our destination of Amed in the eastern regency of Karangasem – an exotic royal Balinese kingdom of forests and mighty mountains, emerald rice terraces, mystical water palaces and pretty beaches. With our tour leader providing information along the way, we will stop at Tenganan Village, a community that still holds to the ancient 'Bali Aga' culture with its original traditions, ceremonies and rules of ancient Bali, and its unique village layout and architecture. We’ll also visit the royal water palace of Tirta Gangga, a fabled maze of spine-tinglingy, cold water pools and basins, spouts, tiered pagoda fountains, stone carvings and lush gardens. The final part of our scenic the journey takes us through a magnificent terrain of sculptured rice terraces followed by spectacular views of a fertile plain extending all the way to the coast. Guarded by the mighty volcano, Gunung Agung, your charming beachside hotel welcomes you with warm Balinese hospitality and traditional architecture, rich with hand-carved ornamentation. -

Indonesian Seas by Global Ocean Associates Prepared for Office of Naval Research – Code 322 PO

An Atlas of Oceanic Internal Solitary Waves (February 2004) Indonesian Seas by Global Ocean Associates Prepared for Office of Naval Research – Code 322 PO Indonesian Seas • Bali Sea • Flores Sea • Molucca Sea • Banda Sea • Java Sea • Savu Sea • Cream Sea • Makassar Strait Overview The Indonesian Seas are the regional bodies of water in and around the Indonesian Archipelago. The seas extend between approximately 12o S to 3o N and 110o to 132oE (Figure 1). The region separates the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Figure 1. Bathymetry of the Indonesian Archipelago. [Smith and Sandwell, 1997] Observations Indonesian Archipelago is most extensive archipelago in the world with more than 15,000 islands. The shallow bathymetry and the strong tidal currents between the islands give rise to the generation of internal waves throughout the archipelago. As a result there are a very 453 An Atlas of Oceanic Internal Solitary Waves (February 2004) Indonesian Seas by Global Ocean Associates Prepared for Office of Naval Research – Code 322 PO large number of internal wave sources throughout the region. Since the Indonesian Seas boarder the equator, the stratification of the waters in this sea area does not change very much with season, and internal wave activity is expected to take place all year round. Table 2 shows the months of the year during which internal waves have been observed in the Bali, Molucca, Banda and Savu Seas Table 1 - Months when internal waves have been observed in the Bali Sea. (Numbers indicate unique dates in that month when waves have been noted) Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec 12111 11323 Months when Internal Waves have been observed in the Molucca Sea.