Number, Colour and Kinship in New Zealand Sign Language Rachel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Report, Vol

CRL Technical Report, Vol. 19 No. 1, March 2007 CENTER FOR RESEARCH IN LANGUAGE March 2007 Vol. 19, No. 1 CRL Technical Reports, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla CA 92093-0526 Tel: (858) 534-2536 • E-mail: [email protected] • WWW: http://crl.ucsd.edu/newsletter/current/TechReports/articles.html TECHNICAL REPORT Arab Sign Languages: A Lexical Comparison Kinda Al-Fityani Department of Communication, University of California, San Diego EDITOR’S NOTE The CRL Technical Report replaces the feature article previously published with every issue of the CRL Newsletter. The Newsletter is now limited to announcements and news concerning the CENTER FOR RESEARCH IN LANGUAGE. CRL is a research center at the University of California, San Diego that unites the efforts of fields such as Cognitive Science, Linguistics, Psychology, Computer Science, Sociology, and Philosophy, all who share an interest in language. The Newsletter can be found at http://crl.ucsd.edu/newsletter/current/TechReports/articles.html. The Technical Reports are also produced and published by CRL and feature papers related to language and cognition (distributed via the World Wide Web). We welcome response from friends and colleagues at UCSD as well as other institutions. Please visit our web site at http://crl.ucsd.edu. SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION If you know of others who would be interested in receiving the Newsletter and the Technical Reports, you may add them to our email subscription list by sending an email to [email protected] with the line "subscribe newsletter <email-address>" in the body of the message (e.g., subscribe newsletter [email protected]). -

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

A Lexicostatistic Survey of the Signed Languages in Nepal

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2012-021 ® A Lexicostatistic Survey of the Signed Languages in Nepal Hope M. Hurlbut A Lexicostatistic Survey of the Signed Languages in Nepal Hope M. Hurlbut SIL International ® 2012 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2012-021, June 2012 © 2012 Hope M. Hurlbut and SIL International ® All rights reserved 2 Contents 0. Introduction 1.0 The Deaf 1.1 The deaf of Nepal 1.2 Deaf associations 1.3 History of deaf education in Nepal 1.4 Outside influences on Nepali Sign Language 2.0 The Purpose of the Survey 3.0 Research Questions 4.0 Approach 5.0 The survey trip 5.1 Kathmandu 5.2 Surkhet 5.3 Jumla 5.4 Pokhara 5.5 Ghandruk 5.6 Dharan 5.7 Rajbiraj 6.0 Methodology 7.0 Analysis and results 7.1 Analysis of the wordlists 7.2 Interpretation criteria 7.2.1 Results of the survey 7.2.2 Village signed languages 8.0 Conclusion Appendix Sample of Nepali Sign Language Wordlist (Pages 1–6) References 3 Abstract This report concerns a 2006 lexicostatistical survey of the signed languages of Nepal. Wordlists and stories were collected in several towns of Nepal from Deaf school leavers who were considered to be representative of the Nepali Deaf. In each city or town there was a school for the Deaf either run by the government or run by one of the Deaf Associations. The wordlists were transcribed by hand using the SignWriting orthography. Two other places were visited where it was learned that there were possibly unique sign languages, in Jumla District, and also in Ghandruk (a village in Kaski District). -

Sign Language Endangerment and Linguistic Diversity Ben Braithwaite

RESEARCH REPORT Sign language endangerment and linguistic diversity Ben Braithwaite University of the West Indies at St. Augustine It has become increasingly clear that current threats to global linguistic diversity are not re - stricted to the loss of spoken languages. Signed languages are vulnerable to familiar patterns of language shift and the global spread of a few influential languages. But the ecologies of signed languages are also affected by genetics, social attitudes toward deafness, educational and public health policies, and a widespread modality chauvinism that views spoken languages as inherently superior or more desirable. This research report reviews what is known about sign language vi - tality and endangerment globally, and considers the responses from communities, governments, and linguists. It is striking how little attention has been paid to sign language vitality, endangerment, and re - vitalization, even as research on signed languages has occupied an increasingly prominent posi - tion in linguistic theory. It is time for linguists from a broader range of backgrounds to consider the causes, consequences, and appropriate responses to current threats to sign language diversity. In doing so, we must articulate more clearly the value of this diversity to the field of linguistics and the responsibilities the field has toward preserving it.* Keywords : language endangerment, language vitality, language documentation, signed languages 1. Introduction. Concerns about sign language endangerment are not new. Almost immediately after the invention of film, the US National Association of the Deaf began producing films to capture American Sign Language (ASL), motivated by a fear within the deaf community that their language was endangered (Schuchman 2004). -

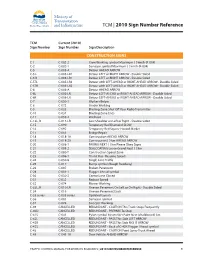

2010 Sign Number Reference for Traffic Control Manual

TCM | 2010 Sign Number Reference TCM Current (2010) Sign Number Sign Number Sign Description CONSTRUCTION SIGNS C-1 C-002-2 Crew Working symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-2 C-002-1 Surveyor symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-5 C-005-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-5 L C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5 R C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5TL C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-5TR C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6 C-006-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-6L C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6R C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-7 C-050-1 Workers Below C-8 C-072 Grader Working C-9 C-033 Blasting Zone Shut Off Your Radio Transmitter C-10 C-034 Blasting Zone Ends C-11 C-059-2 Washout C-13L, R C-013-LR Low Shoulder on Left or Right - Double Sided C-15 C-090 Temporary Red Diamond SLOW C-16 C-092 Temporary Red Square Hazard Marker C-17 C-051 Bridge Repair C-18 C-018-1A Construction AHEAD ARROW C-19 C-018-2A Construction ( ) km AHEAD ARROW C-20 C-008-1 PAVING NEXT ( ) km Please Obey Signs C-21 C-008-2 SEALCOATING Loose Gravel Next ( ) km C-22 C-080-T Construction Speed Zone C-23 C-086-1 Thank You - Resume Speed C-24 C-030-8 Single Lane Traffic C-25 C-017 Bump symbol (Rough Roadway) C-26 C-007 Broken Pavement C-28 C-001-1 Flagger Ahead symbol C-30 C-030-2 Centre Lane Closed C-31 C-032 Reduce Speed C-32 C-074 Mower Working C-33L, R C-010-LR Uneven Pavement On Left or On Right - Double Sided C-34 -

Assessing the Bimodal Bilingual Language Skills of Young Deaf Children

ANZCED/APCD Conference CHRISTCHURCH, NZ 7-10 July 2016 Assessing the bimodal bilingual language skills of young deaf children Elizabeth Levesque PhD What we’ll talk about today Bilingual First Language Acquisition Bimodal bilingualism Bimodal bilingual assessment Measuring parental input Assessment tools Bilingual First Language Acquisition Bilingual literature generally refers to children’s acquisition of two languages as simultaneous or sequential bilingualism (McLaughlin, 1978) Simultaneous: occurring when a child is exposed to both languages within the first three years of life (not be confused with simultaneous communication: speaking and signing at the same time) Sequential: occurs when the second language is acquired after the child’s first three years of life Routes to bilingualism for young children One parent-one language Mixed language use by each person One language used at home, the other at school Designated times, e.g. signing at bath and bed time Language mixing, blending (Lanza, 1992; Vihman & McLaughlin, 1982) Bimodal bilingualism Refers to the use of two language modalities: Vocal: speech Visual-gestural: sign, gesture, non-manual features (Emmorey, Borinstein, & Thompson, 2005) Equal proficiency in both languages across a range of contexts is uncommon Balanced bilingualism: attainment of reasonable competence in both languages to support effective communication with a range of interlocutors (Genesee & Nicoladis, 2006; Grosjean, 2008; Hakuta, 1990) Dispelling the myths….. Infants’ first signs are acquired earlier than first words No significant difference in the emergence of first signs and words - developmental milestones are met within similar timeframes (Johnston & Schembri, 2007) Slight sign language advantage at the one-word stage, perhaps due to features being more visible and contrastive than speech (Meier & Newport,1990) Another myth…. -

American Sign Language

4-H 365.00 General OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION PROJECT IDEA STARTER American Sign Language by Marla Berkowitz, MA, CDI, ASLTA Certified, ASL Program, The Ohio State University; and Kara Detty, Clover Bees 4-H Club Member and Supporter of ASL, Ross County. Special thanks to Abby White, Deaf and Hard of Hearing Educator, Ohio School for the Deaf American Sign Language (ASL) is the official language used mostly by deaf and hard of hearing people who are immersed in the deaf community. The deaf community includes deaf and hard of hearing people, ASL interpreters and hearing people who use ASL and are familiar with deaf culture. Different sign languages such as French, Japanese, British and many more are used all over the world. ASL and its users have influenced our world. For bilingual, using ASL and English for all instruction, and instance, William “Dummy” Hoy (born in 1862) was is located in Washington, D.C. the first deaf baseball superstar and a graduate of As ASL became recognized as a language, it cleared the Ohio School for the Deaf. Hand signals became the path for various laws leading to the Americans necessary for Hoy to understand the plays during the with Disabilities Act in 1990. Most deaf and hard of games. Other players and the fans found them useful hearing people now have better opportunities in a and these signals became commonplace. The football wide array of jobs and careers. huddle was invented in 1892 by Paul Hubbard, a Today, awareness of ASL is growing rapidly and deaf student at Gallaudet University, who urged his classes are now offered in high schools, colleges and teammates to “huddle up” to prevent other teams in local libraries, agencies and other organizations. -

Glossary of Linear Algebra Terms

INNER PRODUCT SPACES AND THE GRAM-SCHMIDT PROCESS A. HAVENS 1. The Dot Product and Orthogonality 1.1. Review of the Dot Product. We first recall the notion of the dot product, which gives us a familiar example of an inner product structure on the real vector spaces Rn. This product is connected to the Euclidean geometry of Rn, via lengths and angles measured in Rn. Later, we will introduce inner product spaces in general, and use their structure to define general notions of length and angle on other vector spaces. Definition 1.1. The dot product of real n-vectors in the Euclidean vector space Rn is the scalar product · : Rn × Rn ! R given by the rule n n ! n X X X (u; v) = uiei; viei 7! uivi : i=1 i=1 i n Here BS := (e1;:::; en) is the standard basis of R . With respect to our conventions on basis and matrix multiplication, we may also express the dot product as the matrix-vector product 2 3 v1 6 7 t î ó 6 . 7 u v = u1 : : : un 6 . 7 : 4 5 vn It is a good exercise to verify the following proposition. Proposition 1.1. Let u; v; w 2 Rn be any real n-vectors, and s; t 2 R be any scalars. The Euclidean dot product (u; v) 7! u · v satisfies the following properties. (i:) The dot product is symmetric: u · v = v · u. (ii:) The dot product is bilinear: • (su) · v = s(u · v) = u · (sv), • (u + v) · w = u · w + v · w. -

What Sign Language Creation Teaches Us About Language Diane Brentari1∗ and Marie Coppola2,3

Focus Article What sign language creation teaches us about language Diane Brentari1∗ and Marie Coppola2,3 How do languages emerge? What are the necessary ingredients and circumstances that permit new languages to form? Various researchers within the disciplines of primatology, anthropology, psychology, and linguistics have offered different answers to this question depending on their perspective. Language acquisition, language evolution, primate communication, and the study of spoken varieties of pidgin and creoles address these issues, but in this article we describe a relatively new and important area that contributes to our understanding of language creation and emergence. Three types of communication systems that use the hands and body to communicate will be the focus of this article: gesture, homesign systems, and sign languages. The focus of this article is to explain why mapping the path from gesture to homesign to sign language has become an important research topic for understanding language emergence, not only for the field of sign languages, but also for language in general. © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. How to cite this article: WIREs Cogn Sci 2012. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1212 INTRODUCTION linguistic community, a language model, and a 21st century mind/brain that well-equip the child for this esearchers in a variety of disciplines offer task. When the very first languages were created different, mostly partial, answers to the question, R the social and physiological conditions were very ‘What are the stages of language creation?’ Language different. Spoken language pidgin varieties can also creation can refer to any number of phylogenic and shed some light on the question of language creation. -

Chimpanzees Use of Sign Language

Chimpanzees’ Use of Sign Language* ROGER S. FOUTS & DEBORAH H. FOUTS Washoe was cross-fostered by humans.1 She was raised as if she were a deaf human child and so acquired the signs of American Sign Language. Her surrogate human family had been the only people she had really known. She had met other humans who occasionally visited and often seen unfamiliar people over the garden fence or going by in cars on the busy residential street that ran next to her home. She never had a pet but she had seen dogs at a distance and did not appear to like them. While on car journeys she would hang out of the window and bang on the car door if she saw one. Dogs were obviously not part of 'our group'; they were different and therefore not to be trusted. Cats fared no better. The occasional cat that might dare to use her back garden as a shortcut was summarily chased out. Bugs were not favourites either. They were to be avoided or, if that was impossible, quickly flicked away. Washoe had accepted the notion of human superiority very readily - almost too readily. Being superior has a very heady quality about it. When Washoe was five she left most of her human companions behind and moved to a primate institute in Oklahoma. The facility housed about twenty-five chimpanzees, and this was where Washoe was to meet her first chimpanzee: imagine never meeting a member of your own species until you were five. After a plane flight Washoe arrived in a sedated state at her new home. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

Rotation Matrix - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 22

Rotation matrix - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 22 Rotation matrix From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia In linear algebra, a rotation matrix is a matrix that is used to perform a rotation in Euclidean space. For example the matrix rotates points in the xy -Cartesian plane counterclockwise through an angle θ about the origin of the Cartesian coordinate system. To perform the rotation, the position of each point must be represented by a column vector v, containing the coordinates of the point. A rotated vector is obtained by using the matrix multiplication Rv (see below for details). In two and three dimensions, rotation matrices are among the simplest algebraic descriptions of rotations, and are used extensively for computations in geometry, physics, and computer graphics. Though most applications involve rotations in two or three dimensions, rotation matrices can be defined for n-dimensional space. Rotation matrices are always square, with real entries. Algebraically, a rotation matrix in n-dimensions is a n × n special orthogonal matrix, i.e. an orthogonal matrix whose determinant is 1: . The set of all rotation matrices forms a group, known as the rotation group or the special orthogonal group. It is a subset of the orthogonal group, which includes reflections and consists of all orthogonal matrices with determinant 1 or -1, and of the special linear group, which includes all volume-preserving transformations and consists of matrices with determinant 1. Contents 1 Rotations in two dimensions 1.1 Non-standard orientation