1 Sets and Set Notation. Definition 1 (Naive Definition of a Set)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linear Algebra I

Linear Algebra I Martin Otto Winter Term 2013/14 Contents 1 Introduction7 1.1 Motivating Examples.......................7 1.1.1 The two-dimensional real plane.............7 1.1.2 Three-dimensional real space............... 14 1.1.3 Systems of linear equations over Rn ........... 15 1.1.4 Linear spaces over Z2 ................... 21 1.2 Basics, Notation and Conventions................ 27 1.2.1 Sets............................ 27 1.2.2 Functions......................... 29 1.2.3 Relations......................... 34 1.2.4 Summations........................ 36 1.2.5 Propositional logic.................... 36 1.2.6 Some common proof patterns.............. 37 1.3 Algebraic Structures....................... 39 1.3.1 Binary operations on a set................ 39 1.3.2 Groups........................... 40 1.3.3 Rings and fields...................... 42 1.3.4 Aside: isomorphisms of algebraic structures...... 44 2 Vector Spaces 47 2.1 Vector spaces over arbitrary fields................ 47 2.1.1 The axioms........................ 48 2.1.2 Examples old and new.................. 50 2.2 Subspaces............................. 53 2.2.1 Linear subspaces..................... 53 2.2.2 Affine subspaces...................... 56 2.3 Aside: affine and linear spaces.................. 58 2.4 Linear dependence and independence.............. 60 3 4 Linear Algebra I | Martin Otto 2013 2.4.1 Linear combinations and spans............. 60 2.4.2 Linear (in)dependence.................. 62 2.5 Bases and dimension....................... 65 2.5.1 Bases............................ 65 2.5.2 Finite-dimensional vector spaces............. 66 2.5.3 Dimensions of linear and affine subspaces........ 71 2.5.4 Existence of bases..................... 72 2.6 Products, sums and quotients of spaces............. 73 2.6.1 Direct products...................... 73 2.6.2 Direct sums of subspaces................ -

Vector Spaces in Physics

San Francisco State University Department of Physics and Astronomy August 6, 2015 Vector Spaces in Physics Notes for Ph 385: Introduction to Theoretical Physics I R. Bland TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. Vectors A. The displacement vector. B. Vector addition. C. Vector products. 1. The scalar product. 2. The vector product. D. Vectors in terms of components. E. Algebraic properties of vectors. 1. Equality. 2. Vector Addition. 3. Multiplication of a vector by a scalar. 4. The zero vector. 5. The negative of a vector. 6. Subtraction of vectors. 7. Algebraic properties of vector addition. F. Properties of a vector space. G. Metric spaces and the scalar product. 1. The scalar product. 2. Definition of a metric space. H. The vector product. I. Dimensionality of a vector space and linear independence. J. Components in a rotated coordinate system. K. Other vector quantities. Chapter 2. The special symbols ij and ijk, the Einstein summation convention, and some group theory. A. The Kronecker delta symbol, ij B. The Einstein summation convention. C. The Levi-Civita totally antisymmetric tensor. Groups. The permutation group. The Levi-Civita symbol. D. The cross Product. E. The triple scalar product. F. The triple vector product. The epsilon killer. Chapter 3. Linear equations and matrices. A. Linear independence of vectors. B. Definition of a matrix. C. The transpose of a matrix. D. The trace of a matrix. E. Addition of matrices and multiplication of a matrix by a scalar. F. Matrix multiplication. G. Properties of matrix multiplication. H. The unit matrix I. Square matrices as members of a group. -

What's in a Name? the Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 9-2008 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2008). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Math Horizons 16.1, 18-21. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/12 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In lieu of an abstract, here is the article's first paragraph: In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix to illustrate the nature of evidence and how it shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician, I usually field questions elatedr to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Disciplines Mathematics Comments Article copyright 2008 by Math Horizons. -

The Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 44-54. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/18 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix (1999) to illustrate how evidence shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician and self-confessed science fiction fan, I usually field questionselated r to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Of course, there are many possible explanations for this, each of which probably contributed a little to the naming decision. -

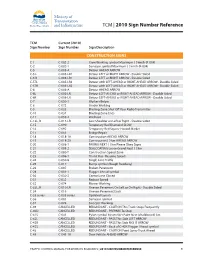

2010 Sign Number Reference for Traffic Control Manual

TCM | 2010 Sign Number Reference TCM Current (2010) Sign Number Sign Number Sign Description CONSTRUCTION SIGNS C-1 C-002-2 Crew Working symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-2 C-002-1 Surveyor symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-5 C-005-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-5 L C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5 R C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5TL C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-5TR C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6 C-006-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-6L C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6R C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-7 C-050-1 Workers Below C-8 C-072 Grader Working C-9 C-033 Blasting Zone Shut Off Your Radio Transmitter C-10 C-034 Blasting Zone Ends C-11 C-059-2 Washout C-13L, R C-013-LR Low Shoulder on Left or Right - Double Sided C-15 C-090 Temporary Red Diamond SLOW C-16 C-092 Temporary Red Square Hazard Marker C-17 C-051 Bridge Repair C-18 C-018-1A Construction AHEAD ARROW C-19 C-018-2A Construction ( ) km AHEAD ARROW C-20 C-008-1 PAVING NEXT ( ) km Please Obey Signs C-21 C-008-2 SEALCOATING Loose Gravel Next ( ) km C-22 C-080-T Construction Speed Zone C-23 C-086-1 Thank You - Resume Speed C-24 C-030-8 Single Lane Traffic C-25 C-017 Bump symbol (Rough Roadway) C-26 C-007 Broken Pavement C-28 C-001-1 Flagger Ahead symbol C-30 C-030-2 Centre Lane Closed C-31 C-032 Reduce Speed C-32 C-074 Mower Working C-33L, R C-010-LR Uneven Pavement On Left or On Right - Double Sided C-34 -

Chapter 4 Complex Numbers Course Number

Chapter 4 Complex Numbers Course Number Section 4.1 Complex Numbers Instructor Objective: In this lesson you learned how to perform operations with Date complex numbers. Important Vocabulary Define each term or concept. Complex numbers The set of numbers obtained by adding real number to real multiples of the imaginary unit i. Complex conjugates A pair of complex numbers of the form a + bi and a – bi. I. The Imaginary Unit i (Page 328) What you should learn How to use the imaginary Mathematicians created an expanded system of numbers using unit i to write complex the imaginary unit i, defined as i = Ö - 1 , because . numbers there is no real number x that can be squared to produce - 1. By definition, i2 = - 1 . For the complex number a + bi, if b = 0, the number a + bi = a is a(n) real number . If b ¹ 0, the number a + bi is a(n) imaginary number .If a = 0, the number a + bi = bi is a(n) pure imaginary number . The set of complex numbers consists of the set of real numbers and the set of imaginary numbers . Two complex numbers a + bi and c + di, written in standard form, are equal to each other if . and only if a = c and b = d. II. Operations with Complex Numbers (Pages 329-330) What you should learn How to add, subtract, and To add two complex numbers, . add the real parts and the multiply complex imaginary parts of the numbers separately. numbers Larson/Hostetler Trigonometry, Sixth Edition Student Success Organizer IAE Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. -

Discover Linear Algebra Incomplete Preliminary Draft

Discover Linear Algebra Incomplete Preliminary Draft Date: November 28, 2017 L´aszl´oBabai in collaboration with Noah Halford All rights reserved. Approved for instructional use only. Commercial distribution prohibited. c 2016 L´aszl´oBabai. Last updated: November 10, 2016 Preface TO BE WRITTEN. Babai: Discover Linear Algebra. ii This chapter last updated August 21, 2016 c 2016 L´aszl´oBabai. Contents Notation ix I Matrix Theory 1 Introduction to Part I 2 1 (F, R) Column Vectors 3 1.1 (F) Column vector basics . 3 1.1.1 The domain of scalars . 3 1.2 (F) Subspaces and span . 6 1.3 (F) Linear independence and the First Miracle of Linear Algebra . 8 1.4 (F) Dot product . 12 1.5 (R) Dot product over R ................................. 14 1.6 (F) Additional exercises . 14 2 (F) Matrices 15 2.1 Matrix basics . 15 2.2 Matrix multiplication . 18 2.3 Arithmetic of diagonal and triangular matrices . 22 2.4 Permutation Matrices . 24 2.5 Additional exercises . 26 3 (F) Matrix Rank 28 3.1 Column and row rank . 28 iii iv CONTENTS 3.2 Elementary operations and Gaussian elimination . 29 3.3 Invariance of column and row rank, the Second Miracle of Linear Algebra . 31 3.4 Matrix rank and invertibility . 33 3.5 Codimension (optional) . 34 3.6 Additional exercises . 35 4 (F) Theory of Systems of Linear Equations I: Qualitative Theory 38 4.1 Homogeneous systems of linear equations . 38 4.2 General systems of linear equations . 40 5 (F, R) Affine and Convex Combinations (optional) 42 5.1 (F) Affine combinations . -

Glossary of Linear Algebra Terms

INNER PRODUCT SPACES AND THE GRAM-SCHMIDT PROCESS A. HAVENS 1. The Dot Product and Orthogonality 1.1. Review of the Dot Product. We first recall the notion of the dot product, which gives us a familiar example of an inner product structure on the real vector spaces Rn. This product is connected to the Euclidean geometry of Rn, via lengths and angles measured in Rn. Later, we will introduce inner product spaces in general, and use their structure to define general notions of length and angle on other vector spaces. Definition 1.1. The dot product of real n-vectors in the Euclidean vector space Rn is the scalar product · : Rn × Rn ! R given by the rule n n ! n X X X (u; v) = uiei; viei 7! uivi : i=1 i=1 i n Here BS := (e1;:::; en) is the standard basis of R . With respect to our conventions on basis and matrix multiplication, we may also express the dot product as the matrix-vector product 2 3 v1 6 7 t î ó 6 . 7 u v = u1 : : : un 6 . 7 : 4 5 vn It is a good exercise to verify the following proposition. Proposition 1.1. Let u; v; w 2 Rn be any real n-vectors, and s; t 2 R be any scalars. The Euclidean dot product (u; v) 7! u · v satisfies the following properties. (i:) The dot product is symmetric: u · v = v · u. (ii:) The dot product is bilinear: • (su) · v = s(u · v) = u · (sv), • (u + v) · w = u · w + v · w. -

An Attempt to Intuitively Introduce the Dot, Wedge, Cross, and Geometric Products

An attempt to intuitively introduce the dot, wedge, cross, and geometric products Peeter Joot March 21, 2008 1 Motivation. Both the NFCM and GAFP books have axiomatic introductions of the gener- alized (vector, blade) dot and wedge products, but there are elements of both that I was unsatisfied with. Perhaps the biggest issue with both is that they aren’t presented in a dumb enough fashion. NFCM presents but does not prove the generalized dot and wedge product operations in terms of symmetric and antisymmetric sums, but it is really the grade operation that is fundamental. You need that to define the dot product of two bivectors for example. GAFP axiomatic presentation is much clearer, but the definition of general- ized wedge product as the totally antisymmetric sum is a bit strange when all the differential forms book give such a different definition. Here I collect some of my notes on how one starts with the geometric prod- uct action on colinear and perpendicular vectors and gets the familiar results for two and three vector products. I may not try to generalize this, but just want to see things presented in a fashion that makes sense to me. 2 Introduction. The aim of this document is to introduce a “new” powerful vector multiplica- tion operation, the geometric product, to a student with some traditional vector algebra background. The geometric product, also called the Clifford product 1, has remained a relatively obscure mathematical subject. This operation actually makes a great deal of vector manipulation simpler than possible with the traditional methods, and provides a way to naturally expresses many geometric concepts. -

Math Object Identifiers – Towards Research Data in Mathematics

Math Object Identifiers – Towards Research Data in Mathematics Michael Kohlhase Computer Science, FAU Erlangen-N¨urnberg Abstract. We propose to develop a system of “Math Object Identi- fiers” (MOIs: digital object identifiers for mathematical concepts, ob- jects, and models) and a process of registering them. These envisioned MOIs constitute a very lightweight form of semantic annotation that can support many knowledge-based workflows in mathematics, e.g. clas- sification of articles via the objects mentioned or object-based search. In essence MOIs are an enabling technology for Linked Open Data for mathematics and thus makes (parts of) the mathematical literature into mathematical research data. 1 Introduction The last years have seen a surge in interest in scaling computer support in scientific research by preserving, making accessible, and managing research data. For most subjects, research data consist in measurement or simulation data about the objects of study, ranging from subatomic particles via weather systems to galaxy clusters. Mathematics has largely been left untouched by this trend, since the objects of study – mathematical concepts, objects, and models – are by and large ab- stract and their properties and relations apply whole classes of objects. There are some exceptions to this, concrete integer sequences, finite groups, or ℓ-functions and modular form are collected and catalogued in mathematical data bases like the OEIS (Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences) [Inc; Slo12], the GAP Group libraries [GAP, Chap. 50], or the LMFDB (ℓ-Functions and Modular Forms Data Base) [LMFDB; Cre16]. Abstract mathematical structures like groups, manifolds, or probability dis- tributions can formalized – usually by definitions – in logical systems, and their relations expressed in form of theorems which can be proved in the logical sys- tems as well. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

Ring (Mathematics) 1 Ring (Mathematics)

Ring (mathematics) 1 Ring (mathematics) In mathematics, a ring is an algebraic structure consisting of a set together with two binary operations usually called addition and multiplication, where the set is an abelian group under addition (called the additive group of the ring) and a monoid under multiplication such that multiplication distributes over addition.a[›] In other words the ring axioms require that addition is commutative, addition and multiplication are associative, multiplication distributes over addition, each element in the set has an additive inverse, and there exists an additive identity. One of the most common examples of a ring is the set of integers endowed with its natural operations of addition and multiplication. Certain variations of the definition of a ring are sometimes employed, and these are outlined later in the article. Polynomials, represented here by curves, form a ring under addition The branch of mathematics that studies rings is known and multiplication. as ring theory. Ring theorists study properties common to both familiar mathematical structures such as integers and polynomials, and to the many less well-known mathematical structures that also satisfy the axioms of ring theory. The ubiquity of rings makes them a central organizing principle of contemporary mathematics.[1] Ring theory may be used to understand fundamental physical laws, such as those underlying special relativity and symmetry phenomena in molecular chemistry. The concept of a ring first arose from attempts to prove Fermat's last theorem, starting with Richard Dedekind in the 1880s. After contributions from other fields, mainly number theory, the ring notion was generalized and firmly established during the 1920s by Emmy Noether and Wolfgang Krull.[2] Modern ring theory—a very active mathematical discipline—studies rings in their own right.