Max Pinckers 5 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

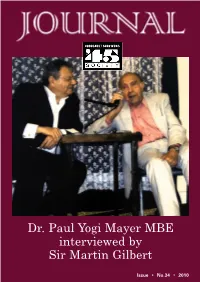

Dr. Paul Yogi Mayer MBE Interviewed by Sir Martin Gilbert

JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 1 Dr. Paul Yogi Mayer MBE interviewed by Sir Martin Gilbert Issue • No.34 • 2010 JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 2 CH ARTER ED AC C OU NTANTS MARTIN HELLER 5 North End Road • London NW11 7RJ Tel 020 8455 6789 • Fax 020 8455 2277 email: [email protected] REGISTERED AUDIT ORS simmons stein & co. SOLI CI TORS Compass House, Pynnacles Close, Stanmore, Middlesex HA7 4AF Telephone 020 8954 8080 Facsimile 020 8954 8900 dx 48904 stanmore web site www.simmons-stein.co.uk Gary Simmons and Jeffrey Stein wish the ’45 Aid every success 2 JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 3 THE ’45 AID SOCIETY (HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS) PRESIDENT SECRETARY SIR MARTIN GILBERT C.B.E.,D.LITT., F.R.S.L M ZWIREK 55 HATLEY AVENUE, BARKINGSIDE, VICE PRESIDENTS IFORD IG6 1EG BEN HELFGOTT M.B.E., D.UNIV. (SOUTHAMPTON) COMMITTEE MEMBERS LORD GREVILLE JANNER OF M BANDEL (WELFARE OFFICER), BRAUNSTONE Q.C. S FREIMAN, M FRIEDMAN, PAUL YOGI MAYER M.B.E. V GREENBERG, S IRVING, ALAN MONTEFIORE, FELLOW OF BALLIOL J KAGAN, B OBUCHOWSKI, COLLEGE, OXFORD H OLMER, I RUDZINSKI, H SPIRO, DAME SIMONE PRENDEGAST D.B.E., J.P., D.L. J GOLDBERGER, D PETERSON, KRULIK WILDER HARRY SPIRO SECRETARY (LONDON) MRS RUBY FRIEDMAN CHAIRMAN BEN HELFGOTT M.B.E., D.UNIV. SECRETARY (MANCHESTER) (SOUTHAMPTON) MRS H ELLIOT VICE CHAIRMAN ZIGI SHIPPER JOURNAL OF THE TREASURER K WILDER ‘45 AID SOCIETY FLAT 10 WATLING MANSIONS, EDITOR WATLING STREET, RADLETT, BEN HELFGOTT HERTS WD7 7NA All submissions for publication in the next issue (including letters to the Editor and Members’ News Items) should be sent to: RUBY FRIEDMAN, 4 BROADLANDS, HILLSIDE ROAD, RADLETT, HERTS WD7 7BX ACK NOW LE DG MEN TS SALEK BENEDICT for the cover design. -

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (AZ Listing by Episode Title. Prices Include

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (A-Z listing by episode title. Prices include taxes and shipping within Canada) Catalog is updated at the end of each month. For current month’s listings, please visit: http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/schedule/ Transcript = readable, printed transcript CD = titles are available on CD, with some exceptions due to copyright = book 104 Pall Mall (2011) CD $18 foremost public intellectuals, Jean The Academic-Industrial Ever since it was founded in 1836, Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Complex London's exclusive Reform Club Spelman Rockefeller Professor of (1982) Transcript $14.00, 2 has been a place where Social and Political Ethics, Divinity hours progressive people meet to School, The University of Chicago. Industries fund academic research discuss radical politics. There's In addition to her many award- and professors develop sideline also a considerable Canadian winning books, Professor Elshtain businesses. This blurring of the connection. IDEAS host Paul writes and lectures widely on dividing line between universities Kennedy takes a guided tour. themes of democracy, ethical and the real world has important dilemmas, religion and politics and implications. Jill Eisen, producer. 1893 and the Idea of Frontier international relations. The 2013 (1993) $14.00, 2 hours Milton K. Wong Lecture is Acadian Women One hundred years ago, the presented by the Laurier (1988) Transcript $14.00, 2 historian Frederick Jackson Turner Institution, UBC Continuing hours declared that the closing of the Studies and the Iona Pacific Inter- Acadians are among the least- frontier meant the end of an era for religious Centre in partnership with known of Canadians. -

A Film Music Documentary

VULTURE PROUDLY SUPPORTS DOC NYC 2016 AMERICA’s lARGEST DOCUMENTARY FESTIVAL Welcome 4 Staff & Sponsors 8 Galas 12 Special Events 15 Visionaries Tribute 18 Viewfinders 20 Metropolis 24 American Perspectives 29 International Perspectives 33 True Crime 36 DEVOURING TV AND FILM. Science Nonfiction 38 Art & Design 40 @DOCNYCfest ALL DAY. EVERY DAY. Wild Life 43 Modern Family 44 Behind the Scenes 46 Schedule 51 Jock Docs 55 Fight the Power 58 Sonic Cinema 60 Shorts 63 DOC NYC U 68 Docs Redux 71 Short List 73 DOC NYC Pro 83 Film Index 100 Map, Pass and Ticket Information 102 #DOCNYC WELCOME WELCOME LET THE DOCS BEGIN! DOC NYC, America’s Largest Documentary hoarders and obsessives, among other Festival, has returned with another eight days fascinating subjects. of the newest and best nonfiction programming to entertain, illuminate and provoke audiences Building off our world premiere screening of in the greatest city in the world. Our seventh Making A Murderer last year, we’ve introduced edition features more than 250 films and panels, a new t rue CriMe section. Other fresh presented by over 300 filmmakers and thematic offerings include SceC i N e special guests! NONfiCtiON, engaging looks at the worlds of science and technology, and a rt & T HE C ITY OF N EW Y ORK , profiles of artists. These join popular O FFICE OF THE M AYOR This documentary feast takes place at our Design N EW Y ORK, NY 10007 familiar venues in Greenwich Village and returning sections: animal-focused THEl wi D Chelsea. The IFC Center, the SVA Theatre and life, unconventional MODerN faMilY Cinepolis Chelsea host our film screenings, while portraits, cinephile celebrations Behi ND the sCeNes, sports-themed JCO k DO s, November 10, 2016 Cinepolis Chelsea once again does double duty activism-oriented , music as the home of DOC NYC PrO, our panel f iGht the POwer and masterclass series for professional and doc strand Son iC CiNeMa and doc classic aspiring documentary filmmakers. -

New Institute's Focus: B'klyn's Untamed Beachfront

w Facebook.com/ Twitter.com Volume 59, No. 87 TUESDAY, AUGUST 13, 2013 BrooklynEagle.com BrooklynEagle @BklynEagle 50¢ BROOKLYN New Institute’s Focus: B’klyn’s Untamed Beachfront TODAY Brooklyn College AUG. 13 Will Host Research About Jamaica Bay Good morning. Today Plans for a new Science and is the 225th day of the Resilience Institute for Jamaica year. On Aug. 13, 1902, Bay were announced on Mon- the Brooklyn Daily Eagle day by Mayor Michael reported that NYPD Cap- Bloomberg and the U.S. Secre- tain Knipe (no first name tary of the Interior Sally Jewell. given) had started a drive Jamaica Bay, which con- to wipe out “bad hotels” tains numerous marshy islands, in Coney Island, probably borders on several Brooklyn meaning brothels. As an and Queens neighborhoods. In example, he mentioned a Brooklyn, it borders on Canar- place where ladies in sie, Bergen Beach, Spring “very short skirts” loi- Creek and Mill Basin; as well as tered outside, but ran in Floyd Bennett Field, which is whenever a cop ap- of Wikipedia courtesy Photo part of Gateway National proached. Knipe said Recreation Area. The institute, which will be these places shouldn’t headed by the City University even have been classified of New York, will promote un- as hotels: “They don’t derstanding of urban ecosys- have the requisite kitchen tems and their adjacent commu- or dining hall, which are nities through an intensive re- required under the law.” search program focused on the Please turn to page 3 restoration of the bay itself. THE WAVES OF JAMAICA BAY ARE SEEN AGAINST PLUMB BEACH IN BROOKLYN, WHICH IS PART OF GATEWAY NATIONAL RECREATION AREA. -

The Delaware & Hudson Was a Classy Railroad!

SUMMER 2016 ■■■■■■■■■■■ VOLUME 36 ■■■■■■■■■■■■ NUMBERS 6 & 7 The Delaware & Hudson was a Classy Railroad! The Semaphore David N. Clinton, Editor-in-Chief CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Southeastern Massachusetts…………………. Paul Cutler, Jr. “The Operator”………………………………… Paul Cutler III Cape Cod News………………………………….Skip Burton Boston Globe Reporter………………………. Brendan Sheehan Boston Herald Reporter……………………… Jim South Wall Street Journal Reporter....………………. Paul Bonanno, Jack Foley Rhode Island News…………………………… Tony Donatelli Empire State News…………………………… Dick Kozlowski Amtrak News……………………………. .. Rick Sutton, Russell Buck “The Chief’s Corner”……………………… . Fred Lockhart PRODUCTION STAFF Publication………………………………… ….. Al Taylor Al Munn Jim Ferris Web Page and photographer…………………… Joe Dumas Guest Contributors ……………………………… The Semaphore is the monthly (except July) newsletter of the South Shore Model Railway Club & Museum (SSMRC) and any opinions found herein are those of the authors thereof and of the Editors and do not necessarily reflect any policies of this organization. The SSMRC, as a non-profit organization, does not endorse any position. Your comments are welcome! Please address all correspondence regarding this publication to: The Semaphore, 11 Hancock Rd., Hingham, MA 02043. ©2015 E-mail: [email protected] Club phone: 781-740-2000. Web page: www.ssmrc.org VOLUME 36 ■■■■■ NUMBERS 6 & 7 ■■■■■ JUNE-JULY 2016 CLUB OFFICERS BILL OF LADING President………………….Jack Foley Vice-President…….. …..Dan Peterson Chief’s Corner ...... …….….3 Treasurer………………....Will Baker Contests ................ ………..3 Secretary……………….....Dave Clinton Clinic……………..……….6 Chief Engineer……….. .Fred Lockhart Directors……………… ...Bill Garvey (’18) Editor’s Notes. ….……….11 ……………………….. .Bryan Miller (‘18) ……………………… ….Roger St. Peter (’17) Election Results ... ………..3 …………………………...Rick Sutton (Temp) Members .............. ……....11 Memories ............. ………..4 The Operator ........ ……….14 Potpourri .............. .……….6 On the cover: 1993 was the D&H’s Sesquicentennial Running Extra ..... -

2020 DISNEY ENTERPRISES, INC. CAST Stargirl Caraway

© 2020 DISNEY ENTERPRISES, INC. CAST Stargirl Caraway . GRACE VANDERWAAL Leo Borlock . GRAHAM VERCHERE DISNEY Archie . .GIANCARLO ESPOSITO presents Mr. Robineau . MAXIMILANO HERNANDEZ Kevin Singh . KARAN BRAR A Tess Reed . .ANNACHESKA BROWN GOTHAM GROUP Benny Burrito . COLLIN BLACKFORD Production Dori Dilson . ALLISON WENTWORTH Alan Ferko . JULIOCESAR CHAVEZ In Association with Mallory Franklin . ARTEMIS HAHNSCAPE ENTERTAINMENT Summer . JULIA FLORES Kim . GABRIELLA SURODJAWAN Hillary Kimble . .SHELBY SIMMONS Wayne Parnell. JOHN APOLINAR Zack James . .ALEX JAMES Gloria Borlock . .DARBY STANCHFIELD Leo Age 8 . ENZO CHARLES DE ANGELIS Cool Girl . CAYMAN GUAY Ana Caraway . .SARA ARRINGTON Principal Sutters . LUCINDA MARKER Band Leader . HANNAH KAUFFMANN Big Kid #1 . GAVIN WILLIAM WHITE Big Kid #2 . SEAN DENNIS Big Kid #3 . .DAVID TRUJILLO Ron Kovak . .TROY BROOKINS Mud Frog Fan . RYAN BEGAY Leo’s Dad . DAMIAN O’HARE Emcee . AUDRA CHARITY Kevin Age 8 . ATHARVA VERMA Teacher . JIMMY E. JONES Young Male Teacher . .ORION C. CARRINGTON Directed by . JULIA HART EMT . THOMAS SONS Screenplay by . KRISTIN HAHN Athletic Trainer . .ERIC ARCHULETA and JULIA HART WINTER DANCE BAND & JORDAN HOROWITZ Keyboard Player . REBECCA ANN ARSCOTT Based on the Novel by . .JERRY SPINELLI Lead Singer/Guitar . HERVE GASPARD Produced by . ELLEN GOLDSMITH-VEIN, p.g.a. Drummer . PAUL PALMER III LEE STOLLMAN, p.g.a. Bass . ARTHA MEADORS KRISTIN HAHN, p.g.a. Mudfrogs Marching Band Executive Producers . .JORDAN HOROWITZ ARMANDO ARELLANO VICTOR ARMIJO JIM POWERS ANDREW BLAIR VINCENT CONTE JERRY SPINELLI GISELLE CRUZ OSCAR GAMBOA EDDIE GAMARRA EDGAR HERNANDEZ GABE HICKS CATHERINE HARDWICKE CHRIS KINGSWADD SHANNON LATHAM JONATHAN LEVIN JULIO QUIROZ LOPEZ SPENSER LOTZ Director of Photography . BRYCE FORTNER GUS PEDROTTY ISIAH ROJAS Production Designer . -

Introduction Chapter 1: Asperger and I

notes INTRODUCTION p. ix “a devastating handicap ...” Uta Frith, “Asperger and His Syndrome,” in Frith, 1991,p.5. p. ix “Paucity of empathy; naive, inappropriate, one-sided social inter- action ...” Klin, Ami, and Fred Volkmar, “Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome,” Yale University Child Study Center, July/August 8–9, 1994. p. xi “the first plausible variant to crystallize out of the autism spectrum ...” Uta Frith, “Asperger and His Syndrome,” in Frith, 1991,p.5. p. xi “More than anything, ADD represents ...” DeGrandpre, 2000,p.39. p. xiii The exchange between Diller and Greene can be read in the archives of Salon magazine (http://archive.salon.com). The fireworks began with Diller’s review of Greene’s The Explosive Child on July 18, 2001, and Greene’s response on July 19. p. xvi “The path to understanding ...” Hans Asperger as quoted in Klin et al, 2000, p. xii. CHAPTER 1: ASPERGER AND I p. 2 “I like the scenery. I like the schedules.” This and other quotations in this chapter by and about Darius McCollum are from “Irresistible Lure of Subways Keeps Landing Impostor in Jail,” by Dean E. Murphy, The New York Times, August 24, 2000,p.A1. p. 5 “Autism as a subject touches on the deepest questions of ontology ...” Sacks, 1996,p.246. p. 6 “Almost all of my social contacts ...” Sacks, 1996,p.261. p. 8 “America is the first society to be totally dominated ...” Postman, 1994,p. 145. p. 9 “What, after all, is normality?” Uta Frith, “Asperger and His Syn- drome,” in Frith, 1991,p.23. -

The Holocaust As Public History

The University of California at San Diego HIEU 145 Course Number 646637 The Holocaust as Public History Winter, 2009 Professor Deborah Hertz HSS 6024 858 534 5501 Class meets 12---12:50 in Center 113 Please do not send me email messages. Best time to talk is right after class. It is fine to call my office during office hours. You may send a message to me on the Mail section of our WebCT. You may also get messages to me via Ms Dorothy Wagoner, Judaic Studies Program, 858 534 4551; [email protected]. Office Hours: Wednesdays 2-3 and Mondays 11-12 Holocaust Living History Workshop Project Manager: Ms Theresa Kuruc, Office in the Library: Library Resources Office, last cubicle on the right [turn right when you enter the Library] Phone: 534 7661 Email: [email protected] Office hours in her Library office: Tuesdays and Thursdays 11-12 and by appointment Ms Kuruc will hold a weekly two hour open house in the Library Electronic Classroom, just inside the entrance to the library to the left, on Wednesday evenings from 5-7. Students who plan to use the Visual History Archive for their projects should plan to work with her there if possible. If you are working with survivors or high school students, that is the time and place to work with them. Reader: Mr Matthew Valji, [email protected] WebCT The address on the web is: http://webct.ucsd.edu. Your UCSD e-mail address and password will help you gain entry. Call the Academic Computing Office at 4-4061 or 4-2113 if you experience problems. -

Transportation Today, January 2018

Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation Newsletter Issue 19 • January 2018 transportation today Making the grade Railroad research, technology, and teaching are picking up steam at Rutgers inside In spite of the dense railroad network in the New York-New Jersey metro area, no university in the region has a focused railroad research and education program. Rutgers is changing that. p7 In a state crisscrossed by 984 miles of railroad railroads will need in the near future. He is It’s big and bad, and if you see it in action, it will track, Dr. Xiang Liu, assistant professor in the confident that Rutgers’ well-established existing shake you to the core. School of Engineering’s (SOE) Department of relationships with the rail industry—including Civil and Environmental Engineering and a those with the USDOT Federal Railroad Admin- p9 CAIT-affiliated researcher, is bringing his istration (FRA), Association of American Railroads There’s something in the commitment, fresh ideas, and youthful energy (AAR), Amtrak, Conrail, CSX Transportation, air. Get used to it—the to expanding rail research and curriculum at MTA, NJ Transit, PATH, Port Authority of New drone market is just getting started. Rutgers. At the same time, he is helping railroads York and New Jersey, and others—are a strong do business more safely and efficiently. foundation for cultivating even more partnerships. p15 Liu sees an opportunity for Rutgers to fill the With well-deserved recognition for his work and New methods to process rail education and research void by developing more than $1 million in research contracts, Liu’s and use contaminated cutting-edge technological solutions for the indus- efforts are clearly on the right track. -

A Genealogist Reveals the Painful Truth About Three Holocaust Memoirs: They’Re Fiction

discrepancies among names and dates in different translations helped to reveal the author’s true identity. A genealogist reveals the painful truth about three Holocaust memoirs: they’re fiction Untrue Stories BY cAleB dAniloff Detractors have called Sharon Sergeant a witch-hunter, a Holocaust denier, and even a Nazi. 32 BOSTONIA Summer 2009 PHOTograph by vernon doucette Summer 2009 BOSTONIA 33 In her 1997 autobiography, Misha: A Memoire The tools of her profession include photographic timelines and data- of the Holocaust Years, Belgian-born Misha bases — vital records, census reports, Defonseca claimed to have trekked war- property deeds, maps, newspaper interviews, obituaries, phone direc- pocked Europe for four years, starting at the tories — and living relatives. Skype, online records, and blogs have also age of seven, in search of her deported Jewish broadened her reach, and DNA testing parents. Along the way, she wrote, she took up is an option if she needs it. “The generic view of genealogy with a pack of wolves, slipped in and out of the is that it is about tracing relatives, the ‘begats,’” says Sergeant, a board Warsaw Ghetto, and killed a Nazi soldier. member and former programs director with the Massachusetts Genealogical In Europe, the book was a smash, court’s decision by proving the author Council. “It’s evolved.” translated into eighteen languages was a fraud. But her involvement in cracking and made into a hit film. In the It was there online, one day in open three Holocaust hoaxes is about United States, however, it had sold December 2007, that Sharon Sergeant more than an interest in the latest poorly — so poorly that Defonseca (MET’83), now an adjunct faculty technology. -

Diplomarbeit FINAL!

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „The ‘Third Reich’ memoir in the light of postmodern philosophy: historical representability and the gate- keeper’s task of ‘poetry after Auschwitz’“ Verfasserin Christine Schranz angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Margarete Rubik Declaration of Authenticity I confirm to have conceived and written this paper in English all by myself. Quotation from sources are all clearly marked and acknowledged in the bibliographical references either in the footnotes or within the text. Any ideas borrowed and/or passages paraphrased from the works of other authors are truthfully acknowledged and identified in the footnotes. Christine Schranz Hinweis Diese Diplomarbeit hat nachgewiesen, dass die betreffende Kandidatin befähigt ist, wissenschaftliche Themen selbstständig sowie inhaltlich und methodisch vertretbar zu bearbeiten. Da die Korrekturen der Beurteilenden nicht eingetragen sind und das Gutachten nicht beiliegt, ist daher nicht erkenntlich, mit welcher Note diese Arbeit abgeschlossen wurde. Das Spektrum reicht von sehr gut bis genügend. Es wird gebeten, diesen Hinweis bei der Lektüre zu beachten. Acknowledgments Writing this thesis has been challenging and rewarding, and along the way I have been fortunate enough to have the help of friends and mentors. I would like to thank the following people for their contributions: Professor Rubik for trusting me on an “outside the box” topic, for pointing me in the right direction, for her editing and for many helpful suggestions. Doron Rabinovici for sharing his thoughts and research on history and fiction with me in an inspiring interview. -

Assembling Autism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 Assembling Autism Kate Suzanne Jenkins Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/231 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] i ASSEMBLING AUTISM by KATE SUZANNE JENKINS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ii @ 2014 KATE JENKINS All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. NAME Date Chair of Examining Committee NAME Date Executive Officer NAME NAME NAME NAME Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract ASSEMBLING AUTISM by KATE SUZANNE JENKINS Adviser: PATRICIA CLOUGH Autism is a growing social concern because of the epidemic-like growth in diagnoses among children. The lives and experiences of adults who have an autism diagnosis, however, are not as well documented. This dissertation project seeks to resolve that dearth of research. I conducted a year of participant observation at four locations of social, self-advocacy, and peer to peer support groups. I also conducted interviews with leaders and participants. I also participated (as a researcher) in an experiment in social skills acquisition led by participants from my ethnographic field work, fulfilling the planned participatory action research component of my original proposal.