Demographic, Intention to Quit Smoking, and Perception Smoke Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating the Effectiveness of Smoke-Free Policies

IARC HANDBOOKS OF CANCER PREVENTION Tobacco Control International Agency for Research on Cancer World Health Organization Volume 13 Evaluating the Effectiveness of Smoke-free Policies IARC 2009 IARC HANDBOOKS OF CANCER PREVENTION Tobacco Control International Agency for Research on Cancer World Health Organization Volume 13 Evaluating the Effectiveness of Smoke-free Policies IARC 2009 International Agency for Research on Cancer The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) was established in 1965 by the World Health Assembly, as an independently funded organisation within the framework of the World Health Organization. The headquarters of the Agency are in Lyon, France. The Agency conducts a programme of research concentrating particularly on the epidemiology of cancer and the study of potential carcinogens in the human environment. Its field studies are supplemented by biological and chemical research carried out in the Agency’s laboratories in Lyon and, through collaborative research agreements, in national research institutions in many countries. The Agency also conducts a programme for the education and training of personnel for cancer research. The publications of the Agency contribute to the dissemination of authoritative information on different aspects of cancer research. Information about IARC publications, and how to order them, is available via the Internet at: http:// www.iarc.fr/en/publications/index.php. This publication represents the views and opinions of an IARC Working Group on Evaluating the effectiveness of smoke-free policies which met in Lyon, France, 31 March - 5 April 2008. iii IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention Published by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, 150 cours Albert Thomas, 69372 Lyon Cedex 08, France © International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2009 Distributed by WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). -

The Impacts of a Smoking Ban on Gaming Volume and Customers' Satisfaction in the Casino Industry in South Korea

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2015 The Impacts of a Smoking Ban on Gaming Volume and Customers' Satisfaction in the Casino Industry in South Korea Sojeong Lee University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Gaming and Casino Operations Management Commons, Public Health Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Repository Citation Lee, Sojeong, "The Impacts of a Smoking Ban on Gaming Volume and Customers' Satisfaction in the Casino Industry in South Korea" (2015). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2374. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/7645940 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACTS OF A SMOKING BAN ON GAMING VOLUME AND CUSTOMERS’ SATISFACTION IN THE CASINO INDUSTRY IN SOUTH KOREA By Sojeong Lee Bachelor of Tourism in College of Social Sciences Hanyang University Seoul, Korea 1999 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science - Hotel Administration William F. -

Do Smoking Bans Always Hurt the Gaming Industry? Differentiated Impacts on the Market Value of Casino Firms in Macao

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Zhang, Jing Hua; Tam, Kwo Ping; Zhou, Nan Article Do smoking bans always hurt the gaming industry? Differentiated impacts on the market value of casino firms in Macao Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal Provided in Cooperation with: Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) Suggested Citation: Zhang, Jing Hua; Tam, Kwo Ping; Zhou, Nan (2016) : Do smoking bans always hurt the gaming industry? Differentiated impacts on the market value of casino firms in Macao, Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal, ISSN 1864-6042, Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW), Kiel, Vol. 10, Iss. 2016-28, pp. 1-32, http://dx.doi.org/10.5018/economics-ejournal.ja.2016-28 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/147482 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Regulating E-Cigarettes Regulating E-Cigarettes

Regulating E-cigarettes Regulating E-Cigarettes The introduction of electronic cigarettes (or e-cigarettes) in countries around the world poses new challenges to governments wanting to protect youth and reduce tobacco use. Policies governing e-cigarettes must be guided by an assessment of the impact of these products on the pace of progress in reducing the death and disease caused by tobacco use. The evidence around the health harms from e-cigarettes and their impact on young people is evolving. Any assessment of the evidence has to consider the impact on both individual smokers and the population as a whole. While e-cigarettes may have health benefits to individual smokers if they are proven to help smokers quit completely, they are nevertheless harmful to public health if they lead to more young people starting, if they renormalize tobacco use, and/or if they discourage smokers from quitting. The World Health Organization has concluded that e-cigarettes are “undoubtedly harmful” and that countries “that have not banned [e-cigarettes] should consider regulating them as harmful products.” 1 This is consistent with the general obligations of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, which require Parties to the Convention to implement measures for preventing and reducing nicotine addiction. 2 In the absence of effective government regulation, e-cigarettes could create a new generation of nicotine and tobacco users and undermine the progress made in combatting the tobacco epidemic. This policy brief uses a three-step process to assist government officials in determining how to regulate e-cigarettes to fit their country circumstances while balancing competing public health considerations: 1. -

Macau Gaming 27 February 2017

Macau Gaming 27 February 2017 【 2017 outlook: Mass Market Continues To Be The Major Driver Investment Highlights: GGR resumes growth in 2016Q3: According to the DICJ figures, Macau’s gross revenue from Games of Fortune amounted to MOP 60,418million in 2016Q4, as compared to MOP 55,005million in 2016Q3, recording a 10.2% YoY growth in the quarterly GGR. Looking forward in 2017, we estimate Mass GGR, VIP GGR and EBITDA to grow by 13%, 6% and 14% respectively. The long-term prospects for the industry remain attractive, particularly for the Mass segment. Mass market to be the major engine: Mass market represents 47% of the GGR mix in FY2016, and we expect the mass market to further gain importance in the next five years. The strength will be underpinned by 1) increasing visitation to Macau; and 2) the upcoming projects in Cotai, including MGM Cotai and Grand Lisboa Palace. VIP may bottom out, but to be confirmed: The quarterly VIP GGR recorded a 12.7% CASH Research YoY growth in 2016 Q4, represent a strong and the first positive year- on- year [email protected] growth since 2014 Q2. However, with mixed factor such as anti-graft campaign and 27 Feb 2017 capital flow control in China, we remain cautious on the prospect of VIP gaming. It is Cynthia Tam worth noting that the 19th National Congress to be held in 2nd half of 2017 will set Tel: 852-2287-8466 the tone for the upcoming monetary and anti- corruption policy, which in turn have [email protected] a significant impact on Macau VIP gaming. -

Cigarette Package Health Warnings: International Status Report

SEPTEMBER 2018 CIGARETTE PACKAGE SIXTH EDITION HEALTH WARNINGS INTERNATIONAL STATUS REPORT Larger, picture health warnings and plain packaging: The growing worldwide trend This report – Cigarette Package Health Warnings: International Status Report – provides an international overview ranking 206 countries/ jurisdictions based on warning size, and lists those that have finalized requirements for picture warnings. Regional breakdowns are also provided. This report is in its sixth edition, with the fifth edition dated October 2016. There has been tremendous progress internationally in implementing package health warnings, with many countries increasing warning size, more countries requiring picture warnings, and an increasing number of countries requiring multiple rounds of picture warnings. The worldwide trend for larger, picture health warnings is growing and unstoppable, with many more countries in the process of developing such requirements. There is also enormous international momentum for implementation of plain packaging. Report highlights include: • 118 countries/jurisdictions worldwide have now required picture • Here are the top counties/territories in terms of health warning size as warnings, representing a global public health achievement. By the end an average of the front and back: of 2016, 100 countries/jurisdictions had implemented picture warnings. Front Back Canada was the first country to implement picture warnings in 2001. 1st 92.5% Timor-Leste 85% 100% • Altogether 58% of the world’s population is covered by the 118 2nd 90% Nepal 90% 90% countries/jurisdictions that have finalized picture warning requirements. 2nd 90% Vanuatu 90% 90% 4th 87.5% New Zealand 75% 100% • Timor-Leste (East Timor) now has the largest warning requirements in 5th 85% Hong Kong (S.A.R., China) 85% 85% the world at 92.5% on average of the package front and back. -

World Bank Document

HNP DISCUSSION PAPER Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Economics of Tobacco Control Paper No. 21 Research on Tobacco in China: About this series... An annotated bibliography of research on tobacco This series is produced by the Health, Nutrition, and Population Family (HNP) of the World Bank’s Human Development Network. The papers in this series aim to provide a vehicle for use, health effects, policies, farming and industry publishing preliminary and unpolished results on HNP topics to encourage discussion and Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized debate. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author(s) and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. Citation and the use of material presented in this series should take into account this provisional character. For free copies of papers in this series please contact the individual authors whose name appears on the paper. Joy de Beyer, Nina Kollars, Nancy Edwards, and Harold Cheung Enquiries about the series and submissions should be made directly to the Managing Editor Joy de Beyer ([email protected]) or HNP Advisory Service ([email protected], tel 202 473-2256, fax 202 522-3234). For more information, see also www.worldbank.org/hnppublications. The Economics of Tobacco Control sub-series is produced jointly with the Tobacco Free Initiative of the World Health Organization. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized manner to the World Health Organization or to the World Bank, their affiliated organizations or members of their Executive Boards or the countries they represent. -

Download Attached File

Response to Invited Reader 1 We are grateful for the comments of the anonymous reader. We response as follows. 1) COMMENT: "The paper can make more contributions to the field with a theoretical model. The casinos have at least four types of customers (smoking and non-smoking gamblers and non-gamblers).... The authors can think about the game theory approach to develop a solid theoretical foundation for the paper." Answer: Considering the suggestions of the anonymous reader, we have decided to include a theoretical model which we had developed in our earlier draft. The model analyzes the dominant strategy of a casino facing smoking bans. " The expected profits of the casinos The accounting profit of gaming product i can be calculated as follows: πi= pi * qi - ci (1) where pi refers to the price, qi refers to the demanded quantity, and ci refers to the typical operating cost of gaming product i. Since it is very difficult for a casino employee to provide sufficient evidence of damage to health due to working in the smoking work environment, the legal cost for second hand smoking health damage compensation claimed by casino employees is not yet a realistic threat to the casinos in Macao. Due to this consideration, we don’t include this type of cost in Equation (1). We consider a general linear differentiated product demand curve for gaming product i facing substitutes gaming product j as in Deneckere and Davidson (1985). (2) The impacts of a smoking ban enter the demand function through changing the value (V) that patrons are willing to attach to the gaming activities according to their smoking preferences. -

Effectiveness of Interventions to Reduce Exposure to Parental Secondhand Smoke at Home Among Children in China: a Systematic Review

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Effectiveness of Interventions to Reduce Exposure to Parental Secondhand Smoke at Home among Children in China: A Systematic Review Yan Hua Zhou 1 , Yim Wah Mak 2,* and Grace W. K. Ho 2 1 School of Nursing, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou 310051, China; [email protected] 2 School of Nursing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong 999077, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-(852)-2766-6421 Received: 7 December 2018; Accepted: 28 December 2018; Published: 3 January 2019 Abstract: There are health consequences to exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS). About two-thirds of children in China live with at least one person, usually a parent, who smokes at home. However, none of the reviews of interventions for reducing SHS have targeted children in China. The purpose of this study was to review the effectiveness of interventions for reducing parental SHS exposure at home among children in China. We searched various electronic databases for English and Chinese publications appearing between 1997 and 2017. Thirteen relevant studies were identified. Common strategies used in intervention groups were non-pharmacological approaches such as counseling plus self-help materials, and attempting to persuade fathers to quit smoking. Family interactions and follow-up sessions providing counseling or using text messages could be helpful to successful quitting. Several encouraging results were observed, including lower cotinine levels in children (n = 2), reduced tobacco consumption (n = 5), and increased quit rates (n = 6) among parents. -

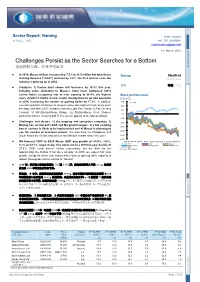

Challenges Persist As the Sector Searches for a Bottom

Sector Report: Gaming Noah Hudson 行业报告:博彩 +86 755 23976684 [email protected] 国泰君安研究 国泰君安研究 13 March 2015 Challenges Persist as the Sector Searches for a Bottom GTJA Research Research GTJA 挑战仍然存在,行业寻找底部 Research GTJA In 2014, Macau visitors increased by 7.5% to 31.5 million but total Gross Rating: Neutral Gaming Revenue (“GGR”) declined by 2.6%, the first decline since the Downgraded industry’s opening up in 2002. 评级: 中性 (下调) Catalysts: 1) Casino hotel rooms will increases by 18.9% this year, bringing some alleviation to Macau’s hotel room bottleneck (2014 casino hotels occupancy was at near capacity at 96.4%, the highest Stock performance ever). 2) US$7.3 billion in new casino development to go into operation 股价表现 in 2015, increasing the number of gaming tables by 17.5%. In addition, 30.0 % return several important infrastructure projects under development most likely won’t 20.0 be ready until after 2015: 3) Macau Intercity Light Rail Transit, 4) Pac On ferry 10.0 terminal, 5) HK-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge, 6) Zhuhai-Macau New Channel 0.0 pedestrian border crossing and 7) increased capacity at the Macau Airport. (10.0) Challenges and threats: 1) the ongoing anti-corruption campaign, 2) (20.0) Beijing has set low 2015 GDP and M2 growth targets, 3) a full smoking (30.0) ban in casinos is likely to be implemented and 4) Macau is planning to (40.0) cap the number of mainland visitors. We also think the Philippines and South Korea are threats and will cut into Macau’s market share this year. -

Free Legislation on Acute Myocardial Infarction and Stroke Mortality

Original research Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054477 on 28 January 2019. Downloaded from Impact of smoke- free legislation on acute myocardial infarction and stroke mortality: Tianjin, China, 2007– 2015 Hong Xiao,1 Hui Zhang,2 Dezheng Wang,2 Chengfeng Shen,2 Zhongliang Xu,2 Ying Zhang,2 Guohong Jiang,2 Gonghuan Yang,3 Xia Wan,3 Mohsen Naghavi4 For numbered affiliations see ABSTRact which is responsible for approximately 230 000 end of article. Background Smoke- free legislation is an effective way deaths annually.7–9 The results from nation- to protect the population from the harms of secondhand ally representative surveys showed that 54% Correspondence to smoke and has been implemented in many countries. Professor Guohong Jiang, Tianjin of indoor employees smoke or were exposed to Centers for Disease Control and On 31 May 2012, Tianjin became one of the few cities SHS at worksites, 57% of youth were exposed to Prevention, Tianjin, China; in China to implement smoke- free legislation. We SHS inside enclosed public spaces and 44% were jiangguohongtjcdc@ 126. investigated the impact of smoke- free legislation on exposed at home.10 11 com and Professor Gonghuan mortality due to acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and Yang and Professor Xia Wan, Despite the high prevalence of smoking and SHS Institute of Basic Medical stroke in Tianjin. exposure, China lags behind other countries in Sciences, Chinese Academy Methods An interrupted time series design adjusting revising tobacco control legislation at the national of Medical Sciences/School of for underlying secular trends, seasonal patterns, level as required by the WHO FCTC and is the Basic Medicine, Peking Union population size changes and meteorological factors was Medical College, Beijing, only country from the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, conducted to analyse the impact of the smoke- free law 100005, China; China, South Africa) group that has not passed a yangghuan@ vip. -

Tobaccocontrol

DEVELOPMENT IN PRACTICE : -Curbingthe Epidemic 19 8 , Public Disclosure Authorized May 1999 Governmentsand the Economicsof TobaccoControl \.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ......... Public Disclosure Authorized .j4 ", .X; Public Disclosure Authorized r e~: 1$~~~~~~~~~7 Public Disclosure Authorized DEVELOPMENT IN PR ACT ICE Curbing the Epidemic Governments and the Economics of Tobacco Control Curbing the Epidemic Governments and the Economics of Tobacco Control THE WORLD BANK WASHINGTON D.C. © 1999 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/THE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First printing May 1999 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author(s) and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations, or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The material in this publication is copyrighted. The World Bank encourages dissemi- nation of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. Permission to photocopy items for internal or personal use, for the internal or personal use of specific clients, or for educational classroom use is granted by the World Bank, provided that the appropriate fee is paid directly to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA.; telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750- 4470. Please contact the Copyright Clearance Center before photocopying items.