Kathrin Zickermann Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schwarmstedt # Verkehrsgemeinschaft Heidekreis, Breidingstraße 1 B, 29614 Soltau, ` (0 51 91) 98 48 55 Am 24

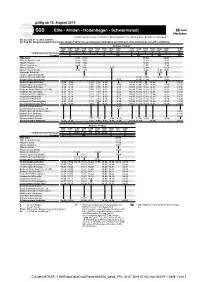

gültig ab 15. August 2019 Q 600 Eilte - Ahlden - Hodenhagen - Schwarmstedt # Verkehrsgemeinschaft Heidekreis, Breidingstraße 1 b, 29614 Soltau, ` (0 51 91) 98 48 55 Am 24. und 31.12. kein Verkehr. Am Tag der Zeugnisausgabe kann es bei einigen Fahrten zu geringfügigen Veränderungen kommen. Bitte informieren Sie sich rechtzeitig. Montag - Freitag 3600 3600 3600 3600 3600 3600 3600 3602 3600 3600 3600 3600 3600 3600 3600 3600 001 201 003 005 007 011 213 007 013 215 017 019 219 021 023 025 Verkehrsbeschränkungen S F S S S S F S S F S S F S S S Hinweise K K 99 K 99 K 99 99 Eilte Süd .637 .7 00 11.58 12. 50 Eilte A.-Borchert-Str. .639 .7 02 11.59 12. 51 Ahlden Hastra .642 .7 05 12.01 12. 53 Ahlden Denkmal .644 .7 07 12.02 12. 54 Ahlden Schule .708 .8 17 12. 04 12. 59 Ahlden Neue Straße .646 .7 10 12.06 13. 00 13. 01 Walsrode Bahnhof 13.19 Hodenhagen Allerstraße Hodenhagen Schulstraße .7 13 11.03 12. 08 13. 04 13. 03 Hodenhagen Heerstraße .815 11. 05 12. 09 13. 04 Hodenhagen Bahnhof .605 .6 05 .7 02 .7 20 .8 05 10.33 11. 00 12.33 13.34 Hodenhagen Grundschule .608 .6 08 .7 05 .7 23 .8 08 .818 10. 36 11. 06 12. 11 12. 36 13. 10 13. 28 Hodenhagen Gutsweg .610 .6 10 .7 07 .7 25 .8 10 .819 10. 37 11. 07 12. 12 12. 37 13. 11 13. -

The German North Sea Ports' Absorption Into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914

From Unification to Integration: The German North Sea Ports' absorption into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914 Henning Kuhlmann Submitted for the award of Master of Philosophy in History Cardiff University 2016 Summary This thesis concentrates on the economic integration of three principal German North Sea ports – Emden, Bremen and Hamburg – into the Bismarckian nation- state. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Emden, Hamburg and Bremen handled a major share of the German Empire’s total overseas trade. However, at the time of the foundation of the Kaiserreich, the cities’ roles within the Empire and the new German nation-state were not yet fully defined. Initially, Hamburg and Bremen insisted upon their traditional role as independent city-states and remained outside the Empire’s customs union. Emden, meanwhile, had welcomed outright annexation by Prussia in 1866. After centuries of economic stagnation, the city had great difficulties competing with Hamburg and Bremen and was hoping for Prussian support. This thesis examines how it was possible to integrate these port cities on an economic and on an underlying level of civic mentalities and local identities. Existing studies have often overlooked the importance that Bismarck attributed to the cultural or indeed the ideological re-alignment of Hamburg and Bremen. Therefore, this study will look at the way the people of Hamburg and Bremen traditionally defined their (liberal) identity and the way this changed during the 1870s and 1880s. It will also investigate the role of the acquisition of colonies during the process of Hamburg and Bremen’s accession. In Hamburg in particular, the agreement to join the customs union had a significant impact on the merchants’ stance on colonialism. -

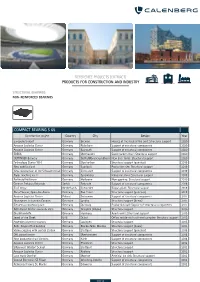

Reference List Construction and Industry

REFERENCE PROJECTS (EXTRACT) PRODUCTS FOR CONSTRUCTION AND INDUSTRY STRUCTURAL BEARINGS NON-REINFORCED BEARINGS COMPACT BEARING S 65 Construction project Country City Design Year Europahafenkopf Germany Bremen Houses at the head of the port: Structural support 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Paderborn Support of structural components 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Bayreuth Support of structural components 2020 EDEKA Germany Oberhausen Supermarket chain: Structural support 2020 OETTINGER Brewery Germany Gotha/Mönchengladbach New beer tanks: Structural support 2020 Technology Center YG-1 Germany Oberkochen Structural support (punctual) 2019 New nobilia plant Germany Saarlouis Production site: Structural support 2019 New construction of the Schwaketenbad Germany Constance Support of structural components 2019 Paper machine no. 2 Germany Spremberg Industrial plant: Structural support 2019 Parkhotel Heilbronn Germany Heilbronn New opening: Structural support 2019 German Embassy Belgrade Serbia Belgrade Support of structural components 2018 Bio Energy Netherlands Coevorden Biogas plant: Structural support 2018 NaturTheater, Open-Air-Arena Germany Bad Elster Structural support (punctual) 2018 Amazon Logistics Center Poland Sosnowiec Support of structural components 2017 Novozymes Innovation Campus Denmark Lyngby Structural support (linear) 2017 Siemens compressor plant Germany Duisburg Production hall: Support of structural components 2017 DAV Alpine Centre swoboda alpin Germany Kempten (Allgäu) Structural support 2016 Glasbläserhöfe -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Invasions, Insurgency and Interventions: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark 1654 - 1658. A Dissertation Presented by Christopher Adam Gennari to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University May 2010 Copyright by Christopher Adam Gennari 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Christopher Adam Gennari We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Ian Roxborough – Dissertation Advisor, Professor, Department of Sociology. Michael Barnhart - Chairperson of Defense, Distinguished Teaching Professor, Department of History. Gary Marker, Professor, Department of History. Alix Cooper, Associate Professor, Department of History. Daniel Levy, Department of Sociology, SUNY Stony Brook. This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School """"""""" """"""""""Lawrence Martin "" """""""Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Invasions, Insurgency and Intervention: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark. by Christopher Adam Gennari Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2010 "In 1655 Sweden was the premier military power in northern Europe. When Sweden invaded Poland, in June 1655, it went to war with an army which reflected not only the state’s military and cultural strengths but also its fiscal weaknesses. During 1655 the Swedes won great successes in Poland and captured most of the country. But a series of military decisions transformed the Swedish army from a concentrated, combined-arms force into a mobile but widely dispersed force. -

Telefonverzeichnis

Telefonverzeichnis Geschäftsführung 0561/ 34117 Kassel, Ständeplatz 23 / Ecke ▼ Jordanstraße FAX : 0561 / 2078-599 oder -590 Gregor Vick GF 1.02 2078-550 [email protected] Leistung Kassel 34117 Kassel, Ständeplatz 23 FAX : 0561 / 2078-599 Team 503 0561/ _V-Jobcenter LK Kassel-Team503 ▼ Bereichsleitung BL 2 7.03 2078-411 [email protected] Ute Blaha Teamleitung TL 6.04 2078-418 [email protected] Jörg Brede 503A Ahnatal A - Z Sandra Heyer 503J 6.10 2078-410 [email protected] Espenau A – D Sarah Grede 503R 6.09 2078-426 [email protected] E - Z Marco Osenbrück 503E 6.08 2078-419 Marco.Osenbrü[email protected] Fuldatal A – H, S [email protected] Corinna Bertram 503P 6.16 2078-557 I – R Michaela Mayer 503Q 6.07 2078-516 [email protected] T - Z Sarah Angersbach 503G 6.14 2078-343 [email protected] Helsa A – O, S Sarah Grede 503R 6.09 2078-426 [email protected] P – R, T - Z Helena Zenker 503N 6.12 2078-559 [email protected] Kaufungen B – G, Marco Osenbrück 503E 6.08 2078-419 [email protected] H – O, W - Z Andrea Seifert 503D 6.05 2078-406 [email protected] A, P – V Ann-Kathrin Knauf 503F 6.06 2078-315 [email protected] Nieste A – Z Tanja Ihlefeld 503K 6.17 2078-417 [email protected] 1 Stellvertretung TL 503 (s. -

The Convent of Wesel Jesse Spohnholz Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-64354-9 — The Convent of Wesel Jesse Spohnholz Index More Information Index Aachen, 100, 177 Westphalia-Lippe Division; Utrecht academia, 67, 158, 188, 189–90, 193, 237 Archives; Zeeland Archives Afscheiding (1834), 162 archiving, 221–22 Alaska, 235–37 in the eighteenth century, 140–43, Alba, Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, duke of, 145–46 26, 27–28, 29, 31–33, 71, 97, 147 in the nineteenth century, 179–80, 220 Algemeen Reglement. See General in the seventeenth century, 130–32, Regulation (1816) 195, 220 Algoet, Anthonius, 63, 81–82, 84, 88, 94 in the twentieth century, 219–20, alterity of the past, 219, 228–29, 223, 224 233–34, 242 Arentsz, Jan, 23, 63, 86 America. See North America; United States Arminianism. See Remonstrants of America Arminius, Jacobus, 107, 108 Amsterdam, 23, 26, 54, 135, 144, 145, 219, See also Remonstrants 223–24 Asperen (duchy/province of Amsterdam City Archives (Stadsarchief Gelderland), 89 Amsterdam), 91, 223–25, 227 Asperen, Joannes van, 74, 77, 86, 217 Anabaptism, 18, 29 Assendorf, Herman van, 86 See also Mennonites atheism, 164, 191, 201 Anchorage, 236 Augsburg Confession (1530), 23, 24, 34, anti-Catholicism, 129, 158, 165, 175, 179 40, 53, 76, 97–98, 99, 109–10, 132, antiquarianism, 130, 139, 166–67, 180 169, 203, 231 Antwerp, 17, 28, 82, 85, 86, 95, 104, 211 Austin Friars. See London, Dutch refugee during the Wonderyear, 20–22, 23, church in 25–26, 27, 50, 73, 78, 80, 81, 86, 96, Australia, 3 204–05, 206–08 Austrian Netherlands (1714–97), 159 April Movement (De Aprilbeweging, -

REINER SOLENANDER (1524-1601): an IMPORTANT 16Th CENTURY MEDICAL PRACTITIONER and HIS ORIGINAL REPORT of VESALIUS’ DEATH in 1564

Izvorni znanstveni ~lanak Acta Med Hist Adriat 2015; 13(2);265-286 Original scientific paper UDK: 61(091)(391/399) REINER SOLENANDER (1524-1601): AN IMPORTANT 16th CENTURY MEDICAL PRACTITIONER AND HIS ORIGINAL REPORT OF VESALIUS’ DEATH IN 1564 REINER SOLENANDER (1524.–1601.): ZNAČAJAN MEDICINSKI PRAKTIČAR IZ 16. STOLJEĆA I NJEGOV IZVORNI IZVJEŠTAJ O VEZALOVOJ SMRTI 1564. GODINE Maurits Biesbrouck1, Theodoor Goddeeris2 and Omer Steeno3 Summary Reiner Solenander (1524-1601) was a physician born in the Duchy of Cleves, who got his education at the University of Leuven and at various universities in Italy and in France. Back at home he became the court physician of William V and later of his son John William. In this article his life and works are discussed. A report on the death of Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), noted down by Solenander in May 1566, one year and seven months after the death of Vesalius, is discussed in detail. Due to the importance of that document a copy of its first publication is given, together with a transcription and a translation as well. It indicates that Vesalius did not die in a shipwreck. Key words: Solenander; Mercator; Vesalius; Zakynthos 1 Clinical Pathology, Roeselare (Belgium) member of the ISHM and of the SFHM. 2 Internal medicine - Geriatry, AZ Groeninge, Kortrijk (Belgium). 3 Endocrinology - Andrology, Catholic University of Leuven, member of the ISHM. Corresponding author: Dr. Maurits Biesbrouck. Koning Leopold III laan 52. B-8800 Roeselare. Belgium. Electronic address: [email protected] 265 Not every figure of impor- tance or interest for the bio- graphy of Andreas Vesalius was mentioned by him in his work1. -

Transcript of Spoken Word

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection Interview with Paul Leeser Series Survivors of the Holocaust—Oral History Project of Dayton Ohio Holocaust Survivors in the Miami Valley Ohio. Wright State University in Conjunction with the Jewish Council of Dayton. Interviewer--Rabbi Cary Kozberg Date of Interviews: August 23, 1978 Q: This is Cary Kozberg speaking. I am conducting the first interview with Mr. Paul Leeser in my office at the Temple. Mr. Leeser lives in Richmond, Indiana. This is Wednesday afternoon, August 23, 1978. Mr. Leeser, how old are you? A: Fifty- seven. Q: Where were you born? A: In a city in the Rhineland (Germany) called, at that time, Hanborn(spelled by PL). Today it is a suburb of a larger city called Duisburg (Duisburg is again spelled by PL). It is called today: “Duisburg-Hanborn.” They are both in the Rhineland tare? Part of the German State of Westphalia. Q: Did you grow up there? A: My early years I spent in Hanborn. I went to school there. Then, when I was not quite in high school, that was in 1927 or 1928, we left the Rhineland and moved inland because my parents bought a business there. I continued my education in a little town called Rinteln which is on the Weser River near the town of Hameln in the district of Minden, at the time. The city, today is in the district of Hanover. I continued my grade school education there and had my first religious training. That is religious school and Hebrew school, etc. -

Man As Witch Palgrave Historical Studies in Witchcraft and Magic

Man as Witch Palgrave Historical Studies in Witchcraft and Magic Series Editors: Jonathan Barry, Willem de Blécourt and Owen Davies Titles include: Edward Bever THE REALITIES OF WITCHCRAFT AND POPULAR MAGIC IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE Culture, Cognition and Everyday Life Julian Goodare, Lauren Martin and Joyce Miller WITCHCRAFT AND BELIEF IN EARLY MODERN SCOTLAND Jonathan Roper (editor) CHARMS, CHARMERS AND CHARMING Rolf Schulte MAN AS WITCH Male Witches in Central Europe Forthcoming: Johannes Dillinger MAGICAL TREASURE HUNTING IN EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA A History Soili-Maria Olli TALKING TO DEVILS AND ANGELS IN SCANDINAVIA, 1500–1800 Alison Rowlands WITCHCRAFT AND MASCULINITIES IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE Laura Stokes THE DEMONS OF URBAN REFORM The Rise of Witchcraft Prosecution, 1430–1530 Wanda Wyporska WITCHCRAFT IN EARLY MODERN POLAND, 1500–1800 Palgrave Historical Studies in Witchcraft and Magic Series Standing Order ISBN 978–1403–99566–7 Hardback Series Standing Order ISBN 978–1403–99567–4 Paperback (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. Please contact your bookseller or, in case of difficulty, write to us at the address below with your name and address, the title of the series and one of the ISBNs quoted above. Customer Services Department, Macmillan Distribution Ltd, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS, England. Man as Witch Male Witches in Central Europe Rolf Schulte Historian, University of Kiel, Germany Translated by Linda Froome-Döring © Rolf Schulte 2009 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2009 978-0-230-53702-6 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. -

Kirchengemeinde Schwarmstedt Kommunion Am 5

Konrmanden Kommunionkinder 2019 Du herrschest über das ungestüme Meer; du stillest seine Wellen, wenn sie sich erheben. Psalm 89:9 Wir wünschen allen Konfirmanden und Kommunionkindern einen unvergesslichen Tag und alles Gute für die Zukunft! FENSTER • TÜREN • ROLLLÄDEN • Beratung & Verkauf • Reparaturen • Insektenschutz • Individueller Innenausbau Christian Unterhalt Groß Eilstorf 71 • 29664 Walsrode Tel.: 0172 - 992 66 45 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.montageservice-unterhalt.de Wir wünschen allen EDITORIAL | INHALT LIEBE WZ-LESERINNEN KIRCHENGEMEINDEN UND -LESER, der Wonnemonat Mai ist nicht nur Ahlden Konfirmanden und der Monat, in dem sich regelmäßig 4 | 6 endgültig der Frühling durchsetzt, sondern auch der Monat, in dem Bad Fallingbostel 8 | 10 | 12 traditionell Konrmationen und Kommunionen gefeiert werden – Bomlitz 14 Kommunionkindern auch im Heidekreis. Diesem Ereig- nis würdigt die Walsroder Zeitung erstmalig eine eigene Beilage. Bommelsen 16 Rund 400 junge Menschen aus dem Kirchenkreis Walsrode sowie den Dorfmark 18 einen unvergesslichen Tag und katholischen Kirchengemeinden St. Maria und Heilig Geist treten auch in diesem Jahr wieder durch Düshorn - Ostenholz 20 | 22 die Segnung ins kirchliche Er- alles Gute für die Zukunft! wachsenenalter über. Bundesweit Eickeloh-Hademstorf 24 liegt die Zahl der Konrmandin- nen und Konrmanden seit etwa Gilten/Suderbruch 26 zehn Jahren recht stabil bei rund 250.000. Dies entspricht rund 30 FENSTER • TÜREN • ROLLLÄDEN Prozent und mehr als 90 Prozent Kirchboitzen 28 aller evangelischen Jugendlichen • Beratung & Verkauf eines Jahrgangs. Blickt man et- Meinerdingen 30 | 32 was länger zurück, zeigt sich aber • Reparaturen • Insektenschutz im Kirchenkreis Walsrode doch ein klarer Abwärtstrend. So hat sich Rethem/Kirchwahlingen 34 • Individueller Innenausbau die Zahl der Konrmandinnen und Konrmanden in den vergangenen Schwarmstedt 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 42 25 Jahren mehr als halbiert. -

Evidence from Hamburg's Import Trade, Eightee

Economic History Working Papers No: 266/2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Economic History Department, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, London, UK. T: +44 (0) 20 7955 7084. F: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC HISTORY WORKING PAPERS NO. 266 – AUGUST 2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Email: [email protected] Abstract The study combines information on some 180,000 import declarations for 36 years in 1733–1798 with published prices for forty-odd commodities to produce aggregate and commodity specific estimates of import quantities in Hamburg’s overseas trade. In order to explain the trajectory of imports of specific commodities estimates of simple import demand functions are carried out. Since Hamburg constituted the principal German sea port already at that time, information on its imports can be used to derive tentative statements on the aggregate evolution of Germany’s foreign trade. The main results are as follows: Import quantities grew at an average rate of at least 0.7 per cent between 1736 and 1794, which is a bit faster than the increase of population and GDP, implying an increase in openness. Relative import prices did not fall, which suggests that innovations in transport technology and improvement of business practices played no role in overseas trade growth. -

2020 LOUTH GAA Club Championships Round 2 (Hurling)

2020 LOUTH GAA Club Championships Round 2 (Hurling) Round 3 (Football) Thursday 27th - Monday 31st August Round 2 Results Thursday 20th August 2020-Senior Hurling Championship St Fechins 1-05 Knockbridge 0-11 Friday 21st August 2020-Junior Championship Annaghminnon Rovers 1-10 Sean McDermotts 2-0 Naomh Malachi 0-13 Stabannon Parnells 0-07 LannLéire 3-06 Glyde Rangers 1-05 Saturday 22nd August 2020-Intermediate Championship Cooley Kickhams 0-09 Hunterstown Rovers 1-10 Roche Emmets 0-07 St Brides 2-15 Kilkerley Emmets 0-21 Clan na Gael 16 Sean O’Mahonys 0-13 Fechins 0-11 Sunday 23rd August 2020-Junior Championship Naomh Fionnbarra 0-13 Wolfe Tones 0-10 Sunday 23rd August 2020-Senior Championship St Josephs 2-09 Dundalk Gaels 2-06 Ardee St.Marys 1-12 Newtown Blues -0-14 O'Raghallaighs 2-11 Geraldines 2-11 Naomh Mairtin 2-15 Dreadnots 0-07 Monday 24th August 2020-Junior Championship John Mitchels 3-11 Na Piarsaigh 2-11 St Nicholas 1-06 Westerns 3-10 This Weeks Fixtures Thursday 27th August 2020 Senior Hurling Championship Naomh Moninne v Knockbridge at 7:30pm Friday 28th August 2020 Junior Football Championship Lannleire V Dowdallshill, 7pm Naomh Malachi v Wolfe Tones, 9pm Naomh Fionnbarra v Stabannan Parnells ,9pm Saturday 29th August 2020 Intermediate Football Championship Roche Emmets v St.Kevins, 2pm Sean O'Mahonys v Glen Emmets, 4pm Cooley Kickhams v Dundalk Young Ireland, 6pm Kilkerley Emmets v Oliver Plunketts, 8pm Sunday 30th August 2020 Junior Football Championship Cuchulainn Gaels v Annaghminnon Rovers, 11am Senior Football Championship