Phd Literature Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'About Turn': an Analysis of the Causes of the New Zealand Labour Party's

Newcastle University e-prints Date deposited: 2nd May 2013 Version of file: Author final Peer Review Status: Peer reviewed Citation for item: Reardon J, Gray TS. About Turn: An Analysis of the Causes of the New Zealand Labour Party's Adoption of Neo-Liberal Policies 1984-1990. Political Quarterly 2007, 78(3), 447-455. Further information on publisher website: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com Publisher’s copyright statement: The definitive version is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2007.00872.x Always use the definitive version when citing. Use Policy: The full-text may be used and/or reproduced and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not for profit purposes provided that: A full bibliographic reference is made to the original source A link is made to the metadata record in Newcastle E-prints The full text is not changed in any way. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Robinson Library, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle upon Tyne. NE1 7RU. Tel. 0191 222 6000 ‘About turn’: an analysis of the causes of the New Zealand Labour Party’s adoption of neo- liberal economic policies 1984-1990 John Reardon and Tim Gray School of Geography, Politics and Sociology Newcastle University Abstract This is the inside story of one of the most extraordinary about-turns in policy-making undertaken by a democratically elected political party. -

New Zealand's Green Party and Foreign Troop Deployments: Views, Values and Impacts

New Zealand's Green Party and Foreign Troop Deployments: Views, Values and Impacts By Simon Beuse A Thesis Submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science School of History, Philosophy, Political Science and International Relations Victoria University of Wellington 2010 Content List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................................. 3 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 2 New Zealand‘s Foreign Affairs .......................................................................................... 9 2.1 Public Perceptions ....................................................................................................... 9 2.2 History ....................................................................................................................... 10 2.3 Key Relationships ...................................................................................................... 11 2.4 The Nuclear Issue ...................................................................................................... 12 2.5 South Pacific .............................................................................................................. 14 2.6 Help in Numbers: The United Nations ...................................................................... 15 2.7 Defence Reform 2000 -

Public Leadership—Perspectives and Practices

Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Edited by Paul ‘t Hart and John Uhr Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/public_leadership _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Public leadership pespectives and practices [electronic resource] / editors, Paul ‘t Hart, John Uhr. ISBN: 9781921536304 (pbk.) 9781921536311 (pdf) Series: ANZSOG series Subjects: Leadership Political leadership Civic leaders. Community leadership Other Authors/Contributors: Hart, Paul ‘t. Uhr, John, 1951- Dewey Number: 303.34 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher Images comprising the cover graphic used by permission of: Victorian Department of Planning and Community Development Australian Associated Press Australian Broadcasting Corporation Scoop Media Group (www.scoop.co.nz) Cover graphic based on M. C. Escher’s Hand with Reflecting Sphere, 1935 (Lithograph). Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2008 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University. He is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). -

Where Our Voices Sound Risky Business See More Seymour

Where Our Voices Sound Risky Business See More Seymour Helen Yeung chats with Mermaidens (not the Jordan Margetts takes on Facebook, the Herald Meg Williams delves deep on a dinner date with Harry Potter kind) and that office sex scandal the ACT Party Leader [1] ISSUE ELEVEN CONTENTS 9 10 NEWS COMMUNITY NORTHLAND GRAVE A CHOICE VOICE ROBBING? An interview with the strong Unfortunately for Split Enz, it women behind Shakti Youth appears that history does repeat 13 14 LIFESTYLE FEATURES SHAKEN UP MORE POWER TO THE PUSSY Milkshake hotspots to bring more than just boys to your A look into the growing yard feminist porn industry 28 36 ARTS COLUMNS WRITERS FEST WRAP-UP BRING OUT THE LIONS! Craccum contributors review Mark Fullerton predicts the some literary luminaries outcomes of the forthcoming Lions Series [3] 360° Auckland Abroad Add the world to your degree Auckland Abroad Exchange Programme Application Deadline: July 1, 2017 for exchange in Semester 1, 2018 The 360° Auckland Abroad student exchange programme creates an opportunity for you to complete part of your University of Auckland degree overseas. You may be able to study for a semester or a year at one of our 130 partner universities in 25 countries. Scholarships and financial assistance are available. Come along to an Auckland Abroad information seminar held every Thursday at 2pm in iSPACE (level 4, Student Commons). There are 360° of exciting possibilities. Where will you go? www.auckland.ac.nz/360 [email protected] EDITORIAL Catriona Britton Samantha Gianotti The F-Word Margaret Atwood’s 1985 dystopian novel The in a later interview that the show is “obvious- ain’t about race, man. -

Rationing’ in New Zealand 1968-C.1980

The “Ugly Sister of Welfare” The idea of health care ‘rationing’ in New Zealand 1968-c.1980 Deborah Salter Submitted for the Degree of MA in History Victoria University of Wellington November 2011 Abstract This thesis explores the influence of healthcare ‘rationing’ in New Zealand from 1968 to c.1980. Rationing is a term and concept drawn from health economics and the history of the idea will be traced as well as its influence. The influence of rationing will primarily be explored through case studies: the supply of specialist staff to New Zealand’s public hospitals, the building of hospitals (and specialist units in particular) and the supply of medical technology. This era has been selected for historical examination because of the limited attention paid to it in studies of the health service, and more generally, welfare histories of New Zealand. Often in these studies the 1970s is overshadowed by the period health of reform in the 1980s and 1990s. Contents Acknowledgements List of Acronyms Chapter One, Introduction p. 1 Chapter Two, The road to rationing p. 19 Chapter Three, Rationing and Specialist Treatment p. 44 Chapter Four, Specialist ‘Manpower’ p. 67 Chapter Five, Buildings and Technology p. 90 Conclusion p. 111 Bibliography p. 116 Appendices p. 124 Acknowledgements I would like to thank all those who have supported me in any way, large or small, whilst I was working on this thesis. I would also like to acknowledge the financial support of the Victoria University Masters Scholarship and the F.P Wilson Scholarship in New Zealand History. Thank you to Capital and Coast District Health Board who kindly granted me access to some of their archival holdings. -

Milestones in NZ Sexual Health Compiled by Margaret Sparrow

MILESTONES IN NEW ZEALAND SEXUAL HEALTH by Dr Margaret Sparrow For The Australasian Sexual Health Conference Christchurch, New Zealand, June 2003 To celebrate The 25th Annual General Meeting of the New Zealand Venereological Society And The 25 years since the inaugural meeting of the Society in Wellington on 4 December 1978 And The 15th anniversary of the incorporation of the Australasian College of Sexual Health Physicians on 23 February 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pg Acknowledgments 3 Foreword 4 Glossary of abbreviations 5 Chapter 1 Chronological Synopsis of World Events 7 Chapter 2 New Zealand: Milestones from 1914 to the Present 11 Chapter 3 Dr Bill Platts MBE (1909-2001) 25 Chapter 4 The New Zealand Venereological Society 28 Chapter 5 The Australasian College 45 Chapter 6 International Links 53 Chapter 7 Health Education and Health Promotion 57 Chapter 8 AIDS: Milestones Reflected in the Media 63 Postscript 69 References 70 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr Ross Philpot has always been a role model in demonstrating through his own publications the importance of historical records. Dr Janet Say was as knowledgeable, helpful and encouraging as ever. I drew especially on her international experience to help with the chapter on our international links. Dr Heather Lyttle, now in Perth, greatly enhanced the chapter on Dr Bill Platts with her personal reminiscences. Dr Gordon Scrimgeour read the chapter on the NZVS and remembered some things I had forgotten. I am grateful to John Boyd who some years ago found a copy of “The Shadow over New Zealand” in a second hand bookstore in Wellington. Dr Craig Young kindly read the first three chapters and made useful suggestions. -

Memorandum of Understanding Between the New Zealand National Party and the Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand

Memorandum of Understanding Between The New Zealand National Party and The Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand Purpose The National Party and the Green Party wish to work together to develop policy and legislation in areas of common interest. The purpose of this MoU is to establish a framework within which the Parties can engage in such areas as are identified from time to time. Principles The following principles underpin this working relationship: • Both Parties are fully independent and retain their rights to vote and speak on all issues as they see fit • The intent of both Parties is to establish a good faith working relationship • This agreement is not based on any prerequisite policy commitments Framework To facilitate a working relationship in identified policy areas, the National Party agrees to provide the Green Party: • Access to Ministers and appropriate departmental officials for briefings and advice • Input into the Ministerial decision making process, including Cabinet papers The Green Party agrees: • To consider facilitating government legislation via procedural support on a case by case basis Both Parties agree: • To keep the details of working discussions confidential until negotiations are concluded, whether the result ends in agreement or not • To facilitate this joint working relationship, the leadership of both Parties will meet at least quarterly to monitor progress, assess the overall relationship and to agree areas where joint work will occur • To review this MoU yearly to assess its effectiveness and determine whether it should continue John Key Jeanette Fitzsimons Russel Norman Leader Co-Leader Co-Leader Memorandum of Understanding Signed 8 April 2009 1 Appendix Areas of agreed work will include: 1. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. I agree with the placing of this thesis in the library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with the access for academic purposes. Brno, 30th March 2018 …………………………………………. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. for his kind help and constant guidance throughout my work. Bc. Lukáš Opavský OPAVSKÝ, Lukáš. Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis; Diploma Thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, English Language and Literature Department, 2018. XX p. Supervisor: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Annotation The purpose of this thesis is an analysis of a corpus comprising of opening sentences of articles collected from the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia. Four different quality categories from Wikipedia were chosen, from the total amount of eight, to ensure gathering of a representative sample, for each category there are fifty sentences, the total amount of the sentences altogether is, therefore, two hundred. The sentences will be analysed according to the Firabsian theory of functional sentence perspective in order to discriminate differences both between the quality categories and also within the categories. -

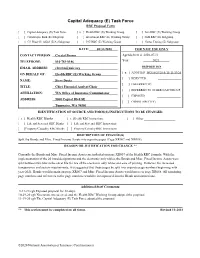

Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force RBC Proposal Form

Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force RBC Proposal Form [ ] Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force [ x ] Health RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Life RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Catastrophe Risk (E) Subgroup [ ] Investment RBC (E) Working Group [ ] SMI RBC (E) Subgroup [ ] C3 Phase II/ AG43 (E/A) Subgroup [ ] P/C RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Stress Testing (E) Subgroup DATE: 08/31/2020 FOR NAIC USE ONLY CONTACT PERSON: Crystal Brown Agenda Item # 2020-07-H TELEPHONE: 816-783-8146 Year 2021 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] DISPOSITION [ x ] ADOPTED WG 10/29/20 & TF 11/19/20 ON BEHALF OF: Health RBC (E) Working Group [ ] REJECTED NAME: Steve Drutz [ ] DEFERRED TO TITLE: Chief Financial Analyst/Chair [ ] REFERRED TO OTHER NAIC GROUP AFFILIATION: WA Office of Insurance Commissioner [ ] EXPOSED ________________ ADDRESS: 5000 Capitol Blvd SE [ ] OTHER (SPECIFY) Tumwater, WA 98501 IDENTIFICATION OF SOURCE AND FORM(S)/INSTRUCTIONS TO BE CHANGED [ x ] Health RBC Blanks [ x ] Health RBC Instructions [ ] Other ___________________ [ ] Life and Fraternal RBC Blanks [ ] Life and Fraternal RBC Instructions [ ] Property/Casualty RBC Blanks [ ] Property/Casualty RBC Instructions DESCRIPTION OF CHANGE(S) Split the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets into separate pages (Page XR007 and XR008). REASON OR JUSTIFICATION FOR CHANGE ** Currently the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets are included on page XR007 of the Health RBC formula. With the implementation of the 20 bond designations and the electronic only tables, the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets were split between two tabs in the excel file for use of the electronic only tables and ease of printing. However, for increased transparency and system requirements, it is suggested that these pages be split into separate page numbers beginning with year-2021. -

Ford Geoffrey

The Green Party Geoffrey Ford Postdoctoral Fellow, UC Arts Digital Lab University of Canterbury, New Zealand [email protected] Citation Ford, G. (2015). The Green Party. In J. Hayward (Ed.), New Zealand government and politics (6th ed., pp. 229-239). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. 1 Introduction The natural environment features strongly in the ways that New Zealanders think about New Zealand. A recurring idealisation of the natural landscape, what Bell calls the ‘nature myth’, is reflected outwards in the ‘clean and green’ image New Zealand presents to the world (Bell 1996). Does this collective idealisation of nature help to explain the long history of green politics in New Zealand? The 2014 general election marked 42 years of green party politics in New Zealand, spanning 15 general elections. It was also the second time that one in ten voters voted for the Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand and the third consecutive election where the Green Party returned to parliament as the third largest party. The longevity and more recent electoral success of green party politics in New Zealand may in part be related to a strong environmental ethic in New Zealand; the Greens are much more than an environmental party. Green parties challenge some of the conventional ways of understanding political parties. Ideology is crucial to understanding the Greens. This chapter explores the development of the Green Party from its activist roots and relates these activist origins to the ideology of the party. It describes how ideology is expressed in the party’s unique approach to organisation and decision-making. -

I Green Politics and the Reformation of Liberal Democratic

Green Politics and the Reformation of Liberal Democratic Institutions. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the University of Canterbury by R.M.Farquhar University of Canterbury 2006 I Contents. Abstract...........................................................................................................VI Introduction....................................................................................................VII Methodology....................................................................................................XIX Part 1. Chapter 1 Critical Theory: Conflict and change, marxism, Horkheimer, Adorno, critique of positivism, instrumental reason, technocracy and the Enlightenment...................................1 1.1 Mannheim’s rehabilitation of ideology and politics. Gramsci and social and political change, hegemony and counter-hegemony. Laclau and Mouffe and radical plural democracy. Talshir and modular ideology............................................................................11 Part 2. Chapter 2 Liberal Democracy: Dryzek’s tripartite conditions for democracy. The struggle for franchise in Britain and New Zealand. Extra-Parliamentary and Parliamentary dynamics. .....................29 2.1 Technocracy, New Zealand and technocracy, globalisation, legitimation crisis. .............................................................................................................................46 Chapter 3 Liberal Democracy-historical -

Identifying Distinct Subgroups of Green Voters: a Latent Profile Analysis of Crux Values Relating to Green Party Support

Subgroups of Green Voters Identifying Distinct Subgroups of Green Voters: A Latent Profile Analysis of Crux Values Relating to Green Party Support Lucy J. Cowie, Lara M. Greaves, Chris G. Sibley University of Auckland, New Zealand Abstract In the present study we aim to explore this possibility by assessing whether The Green Party experienced unprecedented support in the 2011 New there are distinct subgroups of Green Zealand General Election. However, people may vote Green for very voters who differ in terms of their core different reasons. The Green voter base is thus likely to be comprised of social values and level of environmental a number of distinct subpopulations. We employ Latent Profile Analysis concern. to uncover subgroups within the Green voter base (n = 1,663) using data from the New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study at Time Four (2012). We The Green Party of Aotearoa delineate subgroups based on variation in attitudes about the environment, A brief history and context of the equality, wealth, social justice, climate change, and biculturalism. Core Green Green Party is warranted at this point. Liberals (56% of Green voters) showed strong support across all ideological/ The Green Party of Aotearoa can be value domains except wealth, while Green Dissonants (4%) valued the traced as far back as May 1972 to the environment and believed in anthropogenic climate change, but were low formation of the New Zealand Values across other domains. Ambivalent Biculturalists (20%) expressed strong Party, which won 2% of the vote in the support for biculturalism and weak support for social justice and equality.