Understanding Transnational Advocacy Groups: a Case Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Updated October 17, 2017 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44094 Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Summary Bangladesh (the former East Pakistan) is a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia, bordering India, Burma, and the Bay of Bengal. It is the world’s eighth most populous country with nearly 160 million people living in a land area about the size of Iowa. It is an economically poor nation, and it suffers from high levels of corruption. In recent years, its democratic system has faced an array of challenges, including political violence, weak governance, poverty, demographic and environmental strains, and Islamist militancy. The United States has a long-standing and supportive relationship with Bangladesh, and it views Bangladesh as a moderate voice in the Islamic world. In relations with Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, the U.S. government, along with Members of Congress, has focused on a range of issues, especially those relating to economic development, humanitarian concerns, labor rights, human rights, good governance, and counterterrorism. The Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) dominate Bangladeshi politics. When in opposition, both parties have at times sought to regain control of the government through demonstrations, labor strikes, and transport blockades, as well as at the ballot box. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been in office since 2009, and her AL party was reelected in January 2014 with an overwhelming majority in parliament—in part because the BNP, led by Khaleda Zia, boycotted the vote. The BNP has called for new elections, and in recent years, it has organized a series of blockades and strikes. -

A Case Study on Mobilizing Demand for HIV Prevention for Women PATH Is an International Nonprofit Organization That Transforms Global Health Through Innovation

IN OUR OWN HANDS: A case study on mobilizing demand for HIV prevention for women PATH is an international nonprofit organization that transforms global health through innovation. We take an entrepreneurial approach to developing and delivering high-impact, low-cost solutions, from lifesaving vaccines, drugs, diagnostics, and devices to collaborative programs with communities. Through our work in more than 70 countries, PATH and our partners empower people to achieve their full potential. For more information, please visit www.path.org. 455 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 1000 Washington, DC 20001 [email protected] www.path.org Copyright © 2013, Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH). All rights reserved. Cover photo: Frank Herholdt/Microbicides Development Programme IN OUR OWN HANDS: A case study on mobilizing demand for HIV prevention for women By Anna Forbes, Samukeliso Dube, Megan Gottemoeller, Pauline Irungu, Bindiya Patel, Ananthy Thambinayagam, Rebekah Webb, and Katie West Slevin The authors would like to thank the staff of the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College for their invaluable assistance. As the oldest US collection of women’s history manuscripts and archives, the Collection now houses the Global Campaign for Microbicides (GCM) files. The authors would also like to acknowledge all the funders whose support made GCM’s work possible. Most of all, we would like to thank the thousands of women and men who endorsed, supported, and partnered with GCM in doing this work and who are carrying it forward in other ways -

Norman Pearlstine, Chief Content Officer

Mandatory Credit: Bloomberg Politics and the Media Panel: Bridging the Political Divide in the 2012 Elections Breakfast NORMAN PEARLSTINE, CHIEF CONTENT OFFICER, BLOOMBERG, LP: Thank you very much to all of you for coming this afternoon for this panel discussion and welcome to the Bloomberg Link. This is a project that a number of my colleagues have been working very hard on to - to get in shape having had a similar facility in Tampa last week. And as Al Hunt is fond of reminding me, eight years ago, Bloomberg was sharing space as far away from the perimeter and I guess any press could be. I think sharing that space with Al Jazeera -- About four years ago, we certainly had a press presence in Denver and St. Paul, but this year, we're a whole lot more active and a lot more aggressive and I think that reflects all the things that Bloomberg has been doing to increase its presence in Washington where, in the last two years through an acquisition and a start up, we've gone from a 145 journalists working at Bloomberg News to close to 2,000 employees and that reflects in large part the acquisition of BNA last September but also the start up of Bloomberg Government, a web based subscription service. And so over the next few days, we welcome you to come back to the Bloomberg Link for a number of events and hopefully, you'll get a chance to meet a number of my colleagues in the process. I'm very happy that we are able to start our activities in Charlotte with this panel discussion today, not only because of the subject matter, which is so important to journalism and to politics, but also because, quite selfishly, it's given me a chance to partner with Jeff Cowan and Center for Communication Leadership and Policy in Los Angeles at Annenberg USC, which Jeff, I was happy to be a co-chair of your board so, it's good to be able to - each of us to convince the other we ought to do this. -

Naval Reserve Command

NAVAL RESERVE OFFICER TRAINING CORPS Military Science –1 (MS-1) COURSE ORIENTATION Training Regulation A. Introduction: The conduct of this training program is embodied under the provisions of RA 9163 and RA 7077 and the following regulations shall be implemented to all students enrolled in the Military Science Training to produce quality enlisted and officer reservists for the AFP Reserve Force. B. Attendance: 1. A minimum attendance of nine (9) training days or eighty percent (80%) of the total number of ROTC training days per semester shall be required to pass the course. 2. Absence from instructions maybe excuse for sickness, injury or other exceptional circumstances. 3. A cadet/ cadette (basic/advance) who incurs an unexcused absence of more than three (3) training days or twenty percent (20%) of the total number of training during the semester shall no longer be made to continue the course during the school year. 4. Three (3) consecutive absences will automatically drop the student from the course. C. Grading: 1. The school year which is divided into two (2) semesters must conform to the school calendar as practicable. 2. Cadets/ cadettes shall be given a final grade for every semester, such grade to be computed based on the following weights: a. Attendance - - - - - - - - - - 30 points b. Military Aptitude - - - - - 30 points c. Subject Proficiency - - - - 40 points 3. Subject proficiency is forty percent (40%) apportioned to the different subjects of a course depending on the relative importance of the subject and the number of hours devoted to it. It is the sum of the weighted grades of all subjects. -

February 4, 2010

February 4, 2010 475 PARK AVENUE SOUTH, NEW YORK, NY 10016 TEL (212) 686-9700 FAX (212) 686-2172 WWW.MEDIABANKERS.COM Lorne Manly Entertainment Editor Mr. Manly is the entertainment editor of The New York Times. In this role, he oversees the cultural coverage of movies, television and videogames, both in the paper and online. Previously, Mr. Manly was the paper’s film editor, responsible for movie news, feature and reviews; chief media writer, covering trends across the media, entertainment and technology landscapes; and media editor, charged with coverage of the magazine, newspaper, television, movie, music, book publishing and advertising worlds. Before joining The Times in 2002, Mr. Manly worked at Inside as the media editor for its web site, Inside.com, and as the executive editor for its magazine, and served as editorial director for Folio. Mr. Manly has also worked at Brill’s Content as a senior writer and The New York Observer as its media columnist. He began his journalism career at the Toronto Star as a general assignment reporter. Mr. Manly received a BA in political science and history from York University in Toronto, Canada, and graduated with a MS from the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University. Keynote Interview Kevin Mayer was appointed executive vice president of Corporate Strategy, Business Development and Technology in June 2005. Mayer leads the group as it targets emerging businesses new to Disney's existing portfolio, manages cross-divisional issues and opportunities, and evaluates new technology and business models. The group is also Kevin Mayer responsible for the evaluation and execution EVP, Corporate Strategy, of mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures. -

Underwriter Information

A SOCIALLY DISTANCED DESIGN COMPETITION SHOWCASE BENEFITING THE IIDA EDUCATION FUND, TAID, & HOUSTON FURNITURE BANK SAVE THE DATE June 11 th & 12 th CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP TODAY ProductIIDA HOUSTON CITY CENTER Innovate PROUDLY PRESENTS WHAT IS PRODUCT INNOVATE? After a year of uncertainty and disconnect, IIDA Houston City Center presents Product Innovate, a brand-new design challenge showcasing everything 2021 has to offer. IIDA Product Innovate is designed to bring together our community of designers, architects, and students within Houston’s talented architecture and design industry. Since we were unable to celebrate with one another last year and missed out on major life milestones and holidays, the theme for Product Innovate 2021 is Jubilee, a celebration of moments that make each year special. Design teams will be assigned a world- wide celebration or holiday so we can walk though the vignettes and celebrate a year’s worth of memories in one weekend. Teams will be challenged to collect and utilize their myriad talents and expertise to construct an eight-square-foot space that embodies the spirit of the special days we have the opportunity to cherish in 2021. The materials needed to build their designs will consist of sponsor contributions and materials up-cycled from our IIDA Zero Landfill Program. IIDAProduct HOUSTON CITY CENTER Innovate PROUDLY PRESENTS WHAT IS PRODUCT INNOVATE? Fostering community within our industry is chiefly a means to champion philanthropy. IIDA Product Innovate proudly benefits three industry organizations—Houston Furniture Bank, TAID, and the IIDA Texas Oklahoma Chapter Education Fund. The Houston Furniture Bank is a non-profit organization whose mission is to furnish hope by making empty houses, homes. -

Philippine Press Freedom Report 2007

Philippine Press Freedom Report 2007 Philippine Press Freedom Report 2007 Philippine Press Freedom Report 2007 CENTER FOR MEDIA FREEDOM AND RESPONSIBILITY Published by the Philippine Press Freedom Report 2007 Published with the support of the Network Media Program, Open Society Institute CENTER FOR MEDIA FREEDOM AND RESPONSIBILITY PPFJ for MDP.indd 2 9/11/2007 3:58:40 PM Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility Philippine Press Freedom Report 2007 Philippine Press Freedom Report 1 1 9/14/2007 7:24:48 PM Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility: Philippine Press Freedom Report 2007 Published with the support of the Network Media Program, Open Society Institute Copyright © 2007 By the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility ISNN 1908-8299 All rights reserved. No part of this primer may be reproduced in any form or by electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. Philippine Press Freedom Report 2 2 9/14/2007 7:24:48 PM ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A grant from the Network Media Program of the Open Society Institute made this publication possible. Luis V. Teodoro and Rachel E. Khan wrote and edited this primer. Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility staff member Jose Bimbo F. Santos provided research and other support. Photos by Lito Ocampo Cover and layout by Design Plus Philippine Press Freedom Report 3 3 9/14/2007 7:24:48 PM Philippine Press Freedom Report 4 4 9/14/2007 7:24:48 PM CONTENTS Indicators of Press Freedom 8 Trends and Threats 16 The -

2014-2015 Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2014-2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION ABOUT THE IWMF Our mission is to unleash the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. Our vision is for women journalists worldwide to be fully supported, protected, recognized and rewarded for their vital contributions at all levels of the news media. As a result, consumers will increase their demand for news with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives as a cornerstone of democracy and free expression. Photo: IWMF Fellow Sonia Paul Reporting in Uganda 2 IWMF IMPACT REPORT 2014/2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION IWMF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Linda Mason, Co-Chair CBS News (retired) Dear Friends, Alexandra Trower, Co-Chair We are honored to lead the IWMF Board of Directors during this amazing period of growth and renewal for our The Estée Lauder Companies, Inc. Cindi Leive, Co-Vice Chair organization. This expansion is occurring at a time when journalists, under fire and threats in many parts of the Glamour world, need us most. We’re helping in myriad ways, including providing security training for reporting in conflict Bryan Monroe, Co-Vice Chair zones, conducting multifaceted initiatives in Africa and Latin America, and funding individual reporting projects Temple University that are being communicated through the full spectrum of media. Eric Harris, Treasurer Cheddar We couldn’t be more proud of how the IWMF has prioritized smart and strategic growth to maximize our award George A. Lehner, Legal Counsel and fellowship opportunities for women journalists. Through training, support, and opportunities like the Courage Pepper Hamilton LLP in Journalism Awards, the IWMF celebrates the perseverance and commitment of female journalists worldwide. -

Download Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS AN NUAL RE PORT JULY 1, 2003-JUNE 30, 2004 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, NW 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 434-9800 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www.cfr.org E-mail [email protected] OFFICERS and DIRECTORS 2004-2005 OFFICERS DIRECTORS Term Expiring 2009 Peter G. Peterson* Term Expiring 2005 Madeleine K. Albright Chairman of the Board Jessica P Einhorn Richard N. Fostert Carla A. Hills* Louis V Gerstner Jr. Maurice R. Greenbergt Vice Chairman Carla A. Hills*t Robert E. Rubin George J. Mitchell Vice Chairman Robert E. Rubin Joseph S. Nye Jr. Richard N. Haass Warren B. Rudman Fareed Zakaria President Andrew Young Michael R Peters Richard N. Haass ex officio Executive Vice President Term Expiring 2006 Janice L. Murray Jeffrey L. Bewkes Senior Vice President OFFICERS AND and Treasurer Henry S. Bienen DIRECTORS, EMERITUS David Kellogg Lee Cullum AND HONORARY Senior Vice President, Corporate Richard C. Holbrooke Leslie H. Gelb Affairs, and Publisher Joan E. Spero President Emeritus Irina A. Faskianos Vice President, Vin Weber Maurice R. Greenberg Honorary Vice Chairman National Program and Academic Outreach Term Expiring 2007 Charles McC. Mathias Jr. Elise Carlson Lewis Fouad Ajami Director Emeritus Vice President, Membership David Rockefeller Kenneth M. Duberstein and Fellowship Affairs Honorary Chairman Ronald L. Olson James M. Lindsay Robert A. Scalapino Vice President, Director of Peter G. Peterson* t Director Emeritus Studies, Maurice R. Creenberg Chair Lhomas R. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK ------X DEVERE GROUP GMBH

Case 1:11-cv-03360-FB-LB Document 22 Filed 07/13/12 Page 1 of 11 PageID #: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK -------------------------------------------------------------x DEVERE GROUP GMBH, Plaintiff, MEMORANDUM AND ORDER -against- Case No. 11-cv-3360 (FB)(LB) OPINION CORP. d/b/a PISSEDCONSUMER.COM, MICHAEL PODOLSKY, JOANNA SIMPSON and ALEX SYROV, Defendants. -------------------------------------------------------------x Appearances: For the Defendants: For the Plaintiff: RONALD D. COLEMAN, ESQ. CHRISTOPHER R. LOPALO, ESQ. JOEL G. MACMULL, ESQ. Napoli Bern Ripka & Associates LLP Goetz Fitzpatrick LLP 350 Fifth Avenue, Suite 7413 One Penn Plaza, Suite 4401 Great River, New York 11739 New York, New York 10119 MICHAEL D. MYERS, ESQ. Myers & Company, P.L.L.C. 1530 Eastlake Avenue East Seattle, Washington 98102 BLOCK, Senior District Judge: Plaintiff deVere Group GmbH (“deVere”) brings this action for violation of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1051, et seq., against defendants Opinion Corp., Michael Podolsky, Joanna Simpson, and Alex Syrov (collectively, “defendants”).1 Defendants move to dismiss for failure to state a claim, pursuant to Federal Rule of Evidence 12(b)(6). For the following reasons, defendants’ motion is granted. I For purposes of this motion the court must take as true all of the allegations of deVere’s complaint, and must draw all inferences in deVere’s favor. See Weixel v. Board of 1 DeVere also originally brought state law tort claims. Those claims were voluntarily dismissed on October 10, 2011. Case 1:11-cv-03360-FB-LB Document 22 Filed 07/13/12 Page 2 of 11 PageID #: <pageID> Educ., 287 F. -

Advocacy for Refugees and Asylum Seekers Literature Review

A4 ANNEX 1 ACCESS TO HEALTH SERVICES BY MINORITY ETHNIC GROUPS ADVOCACY FOR REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS LITERATURE REVIEW This review covers literature within the following themes: • Advocacy • Language usage • Health of ethnic groups • The 2001 Census, health and immigration • The new Choice Agenda in the NHS • Understanding minority ethnic communities Advocacy 1. Building Bridges for Health – Exploring the potential of advocacy in London, Baljinder Heer, King’s Fund working paper, December 2004 This working paper is part of Putting Health First, a programme of work set up by the King’s Fund to explore the idea of a health system that gives priority to promoting health and reducing inequalities as well as delivering health services. Disadvantaged individuals and groups need effective ways of linking into such a system to ensure they receive the best possible health maintenance and care. We believe that one way of doing this might be to create a stronger cohort of community based advocates to help disadvantaged and socially excluded groups again access to the knowledge and means to secure good health. An advocacy standards framework for BME communities was developed and published in March 2002 and has been used by NW London StHA and Croydon PCT. 2. A Standards Framework for Delivering Effective Health and Social Care Advocacy for Black and Minority Ethnic Londoners, Rukshana Kapasi & Mike Silvera, March 2002, funded by the King’s Fund This is a very detailed report about setting standards for the development of advocacy services for this group of people. A5 3. Health Advocacy for Minority Ethnic Londoners, Mike Silvera and Rukshana Kapasi, November 2000, King’s Fund Vulnerable people can be intimidated by the bureaucracy of statutory services, feeling powerless and voiceless. -

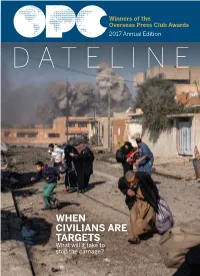

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo).