Help Your Child to Thrive to Child Your Help

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read the Games Transport Plan

GAMES TRANSPORT PLAN 1 Foreword 3 Introduction 4 Purpose of Document 6 Policy and Strategy Background 7 The Games Birmingham 2022 10 The Transport Strategy 14 Transport during the Games 20 Games Family Transportation 51 Creating a Transport Legacy for All 60 Consultation and Engagement 62 Appendix A 64 Appendix B 65 2 1. FOREWORD The West Midlands is the largest urban area outside With the eyes of the world on Birmingham, our key priority will be to Greater London with a population of over 4 million ensure that the region is always kept moving and that every athlete and spectator arrives at their event in plenty of time. Our aim is people. The region has a rich history and a diverse that the Games are fully inclusive, accessible and as sustainable as economy with specialisms in creative industries, possible. We are investing in measures to get as many people walking, cycling or using public transport as their preferred and available finance and manufacturing. means of transport, both to the event and in the longer term as a In recent years, the West Midlands has been going through a positive legacy from these Games. This includes rebuilding confidence renaissance, with significant investment in housing, transport and in sustainable travel and encouraging as many people as possible to jobs. The region has real ambition to play its part on the world stage to take active travel forms of transport (such as walking and cycling) to tackle climate change and has already set challenging targets. increase their levels of physical activity and wellbeing as we emerge from Covid-19 restrictions. -

UC Irvine Learning in the Arts and Sciences

UC Irvine Learning in the Arts and Sciences Title Help Your Child to Thrive: Making the Best of a Struggling Public Education System Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0n72q3n9 ISBN 978-0-9828735-1-9 Author Brouillette, Liane Publication Date 2014 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California FAMILY - CHILDCARE Help Your Child Help Your to Thrive Contemporary public schools focus intensely on academic success. Social-emotional development is given only incidental attention. Families must be prepared to take up the slack. Otherwise students’ emotional growth may be impeded, resulting in diminished social skills, motivation, and ability to cope with stress. This book describes how public schools have changed and provides strategies for helping your child to thrive. Liane Brouillette is an associate professor of education at the University of California, Irvine. Drawing on her experience teaching in public schools in the United States and Europe, she explains how budget cuts, along with LIANE BROUI state and federal mandates, have stretched American teachers thin. She urges parents to be proactive in preparing their children with the tools needed to thrive in contemporary classrooms. LL ETTE Help Your Child to Thrive U.S. $XX.XX Making the Best of a Struggling Public Education System LIANE BROUILLETTE Contents Preface .................................................................................................ix Acknowledgments................................................................................xi -

Eurosport Tells Story of Ski Jumping Ace Ammann's 'Never Ending Flight'

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tuesday, 25 October 2016 EUROSPORT SECURES EXCLUSIVE RIGHTS FOR INAUGURAL SIX DAY CYCLING SERIES BEGINS WEDNESDAY 26 OCTOBER AT 9:30AM AEDT A new series of world-class track cycling events, the Six Day Series, is coming to Eurosport, the Home of Cycling, for its inaugural 2016/17 season. The Six Day Series will feature some of the world’s best professional riders, including Australian team Cameron Meyer and Callum Scotson, Brits Mark Cavendish and Sir Bradley Wiggins, Kenny de Ketele and Moreno de Pauw from Belgium, along with French duo Morgan Kneisky and Benjamin Thomas in a new innovative format, all set within a unique party like atmosphere with great music and entertainment forming the backdrop to the drama on the track. The first event will take place in London at the Lee Valley VeloPark and will be broadcast in Australia Wednesday 26 October at 9:30am (AEDT). Other events in the series include Amsterdam (December), Berlin (January) and Copenhagen (January), with a final night taking place in Palma, Mallorca in March. Held over six consecutive days, the Six Day Series sees teams of two riders compete in multiple races across a variety of sprint and endurance disciplines in a bid to be crowned champions. The cornerstone of the event is the Madison race where the riders sling each other in and out of the action, creating compelling and highly tactical racing. Alongside the elite men, there is an elite women’s omnium competition set to run across the series with men and women riders battling it out to qualify for a one-off, one night spectacular final in Mallorca in March 2017. -

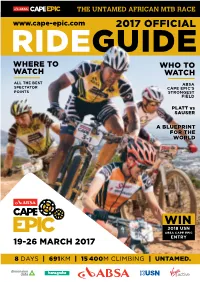

2017 Official Rideguide Where to Who to Watch Watch

THE UNTAMED AFRICAN MTB RACE www.cape-epic.com 2017 OFFICIAL RIDEGUIDE WHERE TO WHO TO WATCH WATCH ALL THE BEST ABSA SPECTATOR CAPE EPIC’S POINTS STRONGEST FIELD PLATT vs SAUSER A BLUEPRINT FOR THE WORLD WIN 2018 USN ABSA CAPE EPIC ENTRY 19-26 MARCH 2017 8 DAYS | 691KM | 15 400M CLIMBING | UNTAMED. A NEW MARK TO BE MEASURED BY The Absa Cape Epic is held in a place where anything can happen: Africa. Wild and open, sometimes inhospitable and other times staggeringly beautiful, this land both tests and surprises all who tackle its ungroomed trails. When the sounds of the cicadas are harsher than the heat they proclaim, when icy mornings lead to driving rain, you can be certain that both equipment and spirit will be pushed to the limit. In this place, where roads hardened year-round by the sun can turn to quicksand overnight, you and your partner will be challenged mentally, physically and emotionally. Yet still, Africa’s untamed majesty beckons. #UNTAMED BOOST ENERGY 3-Stage Glycomatrix carbohydrate BOOST OXYGEN drink for sustained energy during training and racing. Booster for optimal endurance REHYDRATES AND IMPROVES performance optimizer. RECOVERY AFTER TRAINING REPLACES ENERGY DURING INCREASES OXYGEN UPTAKE PHYSICAL ACTIVITY OPTIMIZES MUSCLE PERFORMANCE WHEN BEFORE TRAINING OR EVENT AND DURING WHEN TRAINING AND EVENTS LASTING UP TO TWO DURING TRAINING OR EVENT AS WELL HOURS PREPARE 1 TO 3 HOURS 3 HOURS & MORE Precision formula with carbs, Complete ultra-endurance drink amino acids and electrolytes for optimal performance and for optimal -

Festival Program

THE OFFICIAL 2020 FESTIVAL PROGRAM brisbanecyclingfestival.com WELCOME TO BRISBANE The Hon Kate Jones MP Adrian Schrinner Sean Muir Minister for Tourism Industry Development Lord Mayor of Brisbane CEO, Cycling Queensland Welcome to our state’s capital for the second Welcome to the 2020 Brisbane Cycling Welcome back, year two is set to be bigger annual Brisbane Cycling Festival. Festival. Our New World City is excited to host and better. The Brisbane Cycling Festival will this festival again after a successful inaugural again be bringing amazing world-class events, It is great to see this event return after a event last year. The Brisbane Cycling Festival spectator and recreational riding opportunities successful launch last year. is another wonderful addition to our major to Brisbane. events calendar, providing more to see and do The Queensland Government supports events in our city for residents and visitors alike. Learning to ride a bike as a child is a part of via Tourism and Events Queensland because the Australian culture. The festival is looking they create local jobs in the tourism sector. Brisbane is a great place to live, work, to develop this lifestyle by providing greater The 2019 festival generated 21,794 visitor and relax – it’s a safe, vibrant, green and opportunities for those that currently ride, nights for the region, contributing $4.7 million prosperous city, valued for its friendly, and more incentive for those that want to get to the economy. optimistic character and enjoyable subtropical back on the bike. In doing so, we are bringing lifestyle. together all forms of cycling, from racing to The Queensland Government is proud to recreational riding, road and track. -

Resultaten 2018 ALLE RESULTATEN

2-1-2019 Sport Vlaanderen - Baloise | resultaten 2018 Professional Continental Cycling Team Sport Vlaanderen - Baloise: Resultaten 2018 UCI Europe Tour Ranking 2018 8: Sport Vlaanderen - Baloise Overwinningen weg, niveau UCI 27 mei: Robbe Ghys, Rit/stage 8 Rás Tailteann (2.2, IRL) Overwinningen weg, niveau nationale (kermis)koersen en (derny)criteriums 11 september: Milan Menten, Memorial Briek Schotte, Desselgem (BEL) 27 augustus: Aimé De Gendt, 1ste Grote Prijs Jong maar Moedig / Haaltert (BEL.) 20 augustus: Moreno De Pauw, Dernycriterium 's Gravenwezel (BEL.) Nevenklassementen weg (truien) 28 juli - 1 augustus: Edward Planckaert, Classement des sprints VOO - Tour de Wallonie (2.HC, FRA) 30 mei - 3 juni: Sport Vlaanderen - Baloise, Ploegenklassement Skoda-Tour de Luxembourg (2.HC, LUX) 23 - 27 mei: Thomas Sprengers, Primus Strijdlustklassement Baloise Belgium Tour (2.HC, BEL) 20 - 27 mei: Robbe Ghys, Jongerenklassement Rás Tailteann (2.2) 14 - 18 februari: Aaron Verwilst, meta volantes - tussenspurten Vuelta a Andalucia Ruta Ciclista Del Sol (2.HC ESP) 31 januari - 4 februari: Thomas Sprengers, combiné Volta a la Comunitat Valenciana (2.1 ESP) 31 januari - 4 februari: Preben Van Hecke, bergprijs Volta a la Comunitat Valenciana (2.1 ESP) Overwinningen piste 26 december: Jonas Rickaert, 10 km. puntenkoers, Paarl Boxing Day (ZAF) 22-30 december: Lindsay De Vylder, Omnium, Belgische kampioenschappen baanwielrennen 2018/2019 (BEL) 22-30 december: Moreno De Pauw - Robbe Ghys, Ploegkoers, Belgische kampioenschappen baanwielrennen 2018/2019 -

'El General Naranjo''

Nº 295 • ENERO 2020 • 4 € guia de programación de televisión ‘El General Naranjo’’ Estreno en FOX cableworld El mejor tenis Cine de acción en Eurosport en AMC Pagina_revista_accion.pdf 1 04/12/2019 21:29:28 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K cableworld Canal de TV disponible en todas las plataformas de pago sumario enero 2020 CINE AMC ................................................................................ 8 Canal Hollywood ..................................................... 10 Sundance......................................................................12 Somos ............................................................................15 TCM .................................................................................16 TNT ..................................................................................17 De Pelicula ................................................................. 18 ENTRETENIMIENTO Telenovelas ................................................................. 19 Las Estrellas ............................................................... 20 Robots I am not a Distrito comedia ...................................................... 22 10 Una película de animación para el 12 Hipster Canal Cocina ............................................................. 24 día de Reyes grabada en 2005. Rod- Película sobre la escena musical y ney Hojalata es un joven con un talento especial DeCasa ........................................................................ 25 artística indie en San Diego. Las cosas no pintan para los -

Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games Trade and Investment Program

GOLD COAST 2018 COMMONWEALTH GAMES TRADE AND INVESTMENT PROGRAM EVALUATION REPORT This publication has been compiled by the Office of the Commonwealth Games, Department of Innovation, Tourism Industry Development and the Commonwealth Games. © State of Queensland, 2018. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. 2 • Contents 1. Executive summary ................................................................................................4 2. Introduction .............................................................................................................14 2.1. Commonwealth trade and investment ..........................................................14 2.2. Trade 2018 program .....................................................................................17 -

The Hale Corp. Chatham

li.” ' ............................ Average Daily Circulation The Weather Manchester/^Evehing Herald Rftf^ AY 11 Fnreeuet of D. 8. H’ratber "V _ _______ ^___ t For the Moeth «f Aagaat, 1944 Gale uinds with heevy rulu to Maneheater Twit. No. 7, Kntghta Laurent treasurer, 47 Gerard n a d b 8,77.5 night and’early Friday. Hnrrieah; of the Maccaheea, will meet thia Nurses’sQuota street, Manchester, or, tf more expected to •trike tioiiiheaat Coa--' AttoutTowh evening at A'b’clock in the Batch convenient, may be leR with Me. Member ef the Audit neotteut eoast about uiidnigbt. and Brovni hall, D ^ t Square, and Marte at the Manchester Trust Bureua ef Circulathma Walter• P. Ck>man, ■ aon of •■ Mr. aa thia will be the only meeting Is $1,800 Short Company. M^llinehe»ter--—^4 City of Village Charm r and Mra. W altw P.NObrmaa, of 42 thia m ^th, Commahder J. Albert Brookfield atraet, W\« freahman Oderitliuin hopea for a good at RINGS at Holy CroM Ootlege>Hla broth- tendance of th$ knlghta, inaamuch To Lecture Tonight ^ (ClaioUled 'Adverthdug ou rugu'-tS) MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 1944 \ \ (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE CEl er,“ Rayipond------ - A.* *’->rman;donnan; .alao aat- t aa there ta oonaiderabiS b'Uaineaa Association Appeals for .VOL. LXIIL, 294 tended Holy CroM,Cl and la a xandtxandt-i •to be taken care of. The new own- Contributions to Meet On Current Books date for a IBachelor of Arta.oe^e4^ era have redecorated the hall and Gent's Black. Onyx Rings. .. 921.50 and up in pre-medical made a number of-improvementa. -

Download Now PDF File 14.7 MB

FEBRUARY 2019 £3.50 sportsSPORTS OUTDOOR CYCLING RUNNINGinsight FITNESS TRADE sports-insight.co.uk CYCLING INTERVIEW OUTDOOR I AM SUFFERING LEADS OUTDOOR BY ISPO SPARTACUS! P.28 TO SUCCESS P.45 GATHERS PACE P.34 It’s a great story....We love tape! - we didn’t invent it - it’s been around for a long time d3tape: the southern hemisphere’s fastest growing sports consumable brand is now available in the united kingdom! we’re specialists, focused, retail savy, - not a global pharmaceutical company our aim & belief is to supply exceptional value, quality, honest strapping tape all with a bit of funk, and in a cost effective manner that real people can afford helping you make your consumers lives...better! Sports Insight NOVEMBER.pdf 1 23/11/2018 10:35 RUGBY C M Y CM MY CY CMY K FOOTBALL BASEBALL MANUFACTURERS OF QUALITY PROTECTIVE SPORTSWEAR, MORE INFO? CYCLING CLOTHING, MMA GEAR, FOOTWEAR, TECHNICAL TEL: 01942 497707 SPORTS EQUIPMENT AND HIGH SPECIFICATION TEAMWEAR. [email protected] 4 WELCOME Brooks Run Happy to this month's Sports Insight Team 2019 The running shoe expert From the UK and Ireland, Brooks has put together a 25 applicants were selected to cross-country team of 110 motivate others to run and be active. running enthusiasts for 2019. True to its motto "Run Happy", For the Run Happy Team, the sports shoe manufacturer is Brooks received almost 4000 convinced of the positive power of applicants from passionate running and offers the participants runners from all over Europe of the Run Happy Team the special who want to become part of the opportunity to experience this team and represent the spirit of enthusiasm and share it with others. -

Cover 2018 Final

VOYAGEROYAGER V 2017-2018 HASSARAM RIJHUMAL COLLEGE OF COMMERCE & ECONOMICS Affiliated to the University of Mumbai I/C Principal Mr. Parag Thakkar Vice-Principals Degree College Dr. Jehangir Bharucha Dr. Pooja Ramchandani Dr. Rajeshwari Ravi Librarian Superintendent Admin. Dr. Madhuri Tikam Ms. Jyoti Govindani Editor Graphic Design Dr. Misha Bothra Ms. Kamni Bahl www.hrcollege.edu 1 CONTENTS 1 About Us 3 Present Trustees H(S)NC Board 4 Paying homage to the departed souls 5 From the Desk of the I/C Principal 6 Academics 31 Lectures | Seminars | Workshops 48 Beyond Academics 97 Internationalisation of HR 107 Student Enrichment 149 Our Achievers 151 Annual Prize Distribution Degree College 159 Annual Prize Distribution Junior College 165 Prize Distribution Lists Inside Front Cover Inside Back Cover - Certificate of Accreditation - HSNC Board Info 2 PRESENTTRUSTEESH(S)NCBOARD Mr. Anil Harish Dr. Niranjan Hiranandani President Trustee & Immediate Past President Mr. Anil Harsih, one of the most sought after Leading entrepreneur, the man responsible for legal experts and financial analysts of the transforming the skyline of Mumbai, brings a nation, as President of the Board, brings his fine sense of balance and creativity to the forward looking futuristic vision to bear upon functioning of Board. what the next generation would be aspiring for. Mr. Kishu Mansukhani Mr. Lal Chellaram Trustee & Past President Trustee & Board Member, Mr. Kishu Mansukhani, after a dream career Mr. Chellaram is a businessman with global as CEO with the Tata Group, has devoted presence and a conscientious humanitarian. himself to the promotion of Sindhi culture and He brings with him the fine blend of the language and as the Past President has pragmatic and social commitment to his inspired the Colleges to take this up with a various enterprise in education, healthcare missionary zeal. -

Gold Coast 2018 Post Games Report

GOLD COAST 2018 COMMONWEALTH GAMES REPORT This publication has been compiled by the Office of the Commonwealth Games, Department of Innovation, Tourism Industry Development and the Commonwealth Games. © State of Queensland, 2019. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Cover Image Credit: Getty Images CONTENTS 4 209 Traditional Custodians GAMES GOVERNANCE AND FINANCE acknowledgement 210 Overview 212 GC2018 Partners 5 214 GC2018 Performance 217 Our People Foreword from 220 Governance Minister Kate Jones 222 Governance Groups 225 Managing Risks 6 227 Financial Highlights 229 Dissolution Executive Summary 232 10 APPENDICES CELEBRATING THE GAMES 233 Appendix 1 GC2018 Medal Tally 11 The Gold Coast