BARRIE POLICE SERVICES BOARD (The “Board”)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes Council's Task Force on Affordable Housing Meeting Held on January 5, 2021

"The Town of Midland does not adopt or condone anything said in correspondence or communications provided to it or its Council, and does not warrant the accuracy of statements made in such correspondence or communications. The Town believes it has a duty to ensure that its proceedings and deliberations are transparent, and that it foster public debate on issues of concern. One of the steps it takes to carry out this duty is to, wherever possible, make the material in its Council Information Packages available on its website." Council Information Package February 8 to February 12, 2021 k:\Council&By-laws\C03 Council Agenda\Council Information Packages List Date Sent Out (dd- No. mm-yy) Media Type From Subject 1 12-Feb-2021 Communications AMO Survey on Electronic Permitting [e-permitting] Platforms AMO Policy Update – Gradual Return to COVID-19 Response Framework, Conservation Authorities Act 2 12-Feb-2021 Communications AMO Update 3 12-Feb-2021 Communications AMO AMO WatchFile - February 11, 2021 4 12-Feb-2021 Correspondence Midland Heritage Committee, Member Letter of Resignation - Midland Heritage Committee 5 12-Feb-2021 Media Release Town of Midland Town of Midland on the front lines of Wastewater Surveillance during COVID-19 Pandemic 6 12-Feb-2021 Minutes Huronia Airport Commission Meeting held on December 17, 2020 7 12-Feb-2021 Minutes Council's Task Force on Affordable Housing Meeting held on January 5, 2021 8 12-Feb-2021 News Release OPP News Portal OPP Officers Save Over 200 Lives by Administering Naloxone 9 12-Feb-2021 News Release OPP News Portal 211 - Help Starts Now 10 12-Feb-2021 News Release OPP News Portal OPP Officers Out Conducting R.I.D.E. -

Attachment Council Agenda Bill I

Item: NB #5 City of Arlington Attachment Council Agenda Bill I COUNCIL MEETING DATE: July 6, 2020 SUBJECT: Community Policing, Policy and Accountability ATTACHMENTS: DEPARTMENT OF ORIGIN Presentation, Org Chart, IAPRO, BlueTeam, 2018 Strategic Planning, APD Planning Recommendations Police; Jonathan Ventura, Chief and Human Resources; James Trefry, Administrative Services Director EXPENDITURES REQUESTED: None BUDGET CATEGORY: N/A BUDGETED AMOUNT: 0 LEGAL REVIEW: DESCRIPTION: Presentation by the Chief of Police and the Administrative Services Director regarding the Arlington Police Department. Topics covered include community policing, policy and accountability. HISTORY: The Mayor and Councilmembers have requested a presentation about the current state of the police department in light of current events and feedback received from the community. ALTERNATIVES: Remand to staff for further information. RECOMMENDED MOTION: Information only; no action required. Arlington Police Department COMMUNITY POLICING / POLICY / ACCOUNTABILITY Community Policing Community Outreach Team / LE Embedded Social Worker (LEESW) (2018) Domestic Violence Coordinator (2019) School Resource Officer All-In Program / Conversations with Cops COP’s Building Trust Grant – Funding for 2 Officers (2015) Boards and Commissions Community Meetings 21st Century Policing Initiative Strategic Plan (2018) Virtual Training Simulator (2019) Crime Data (2019) Traffic Enforcement up 32% DUI Enforcement up 14% Burglary reports down 15% Robbery reports down 38% Overall Theft Reporting -

Police Resources in Canada, 2019

Catalogue no. 85-002-X ISSN 1209-6393 Juristat Police resources in Canada, 2019 by Patricia Conor, Sophie Carrière, Suzanne Amey, Sharon Marcellus and Julie Sauvé Release date: December 8, 2020 How to obtain more information For information about this product or the wide range of services and data available from Statistics Canada, visit our website, www.statcan.gc.ca. You can also contact us by email at [email protected] telephone, from Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., at the following numbers: • Statistical Information Service 1-800-263-1136 • National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1-800-363-7629 • Fax line 1-514-283-9350 Depository Services Program • Inquiries line 1-800-635-7943 • Fax line 1-800-565-7757 Standards of service to the public Note of appreciation Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, Canada owes the success of its statistical system to a reliable and courteous manner. To this end, Statistics Canada has long-standing partnership between Statistics Canada, the developed standards of service that its employees observe. To citizens of Canada, its businesses, governments and other obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics institutions. Accurate and timely statistical information could not Canada toll-free at 1-800-263-1136. The service standards are be produced without their continued co-operation and goodwill. also published on www.statcan.gc.ca under “Contact us” > “Standards of service to the public.” Published by authority of the Minister responsible for Statistics Canada © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada as represented by the Minister of Industry, 2020 All rights reserved. -

Police Service (Municipal) Address Phone/Fax Number

Police Service (Municipal) Address Phone/Fax Number Amherstburg Police Service P.O. Box 70 Telephone: (519) 736‐8559 [email protected] 532 Sandwich Street South After Hours: (519) 969‐6650 www.amherstburg.ca/police Amherstburg ON N9V 2Z3 Facsimile: (519) 736‐8310 Aylmer Police 20 Beech Street East Telephone: (519) 773‐3144 www.aylmerpolice.com Aylmer ON N5H 3H6 Facsimile: (519) 765‐1580 Barrie Police Service 29 Sperling Drive Telephone: (705) 725‐7025 [email protected] Barrie ON L4M 6K9 Facsimile: (705) 728‐2971 www.police.barrie.on.ca Belleville Police Service 93 Dundas Street East Telephone: (613) 966‐0882 www.police.belleville.on.ca Belleville ON K8N 1C2 Emergency: (613) 962‐3456 Facsimile: (613) 966‐2701 Brantford Police Service 344 Elgin Street Telephone: (519) 756‐7050 wwwwww.police.brantford.on.ca..police brantford.on.ca BrantfordBrantford,, ON N3T 5T3 Facsimile: (519) 756‐4272 Brockville Police Service 2269 Parkedale Avenue Telephone: (613) 342‐0127 www.brockvillepolice.com Brockville ON K6V 3G9 Facsimile: (613) 342‐0452 [email protected] Chatham‐Kent Police Service 24 Third Street Telephone: (519) 436‐6600 www.ckpolice.com P.O. Box 366 Facsimile: (519) 436‐6643 [email protected] Chatham ON N7M 5K5 Cobourg Police Service 107 King Street West Telephone: (905) 372‐6821 www.town.cobourg.on.ca Cobourg ON K9A 2M4 Facsimile: (905) 372‐8325 [email protected] Police Service (Municipal) Address Phone/Fax Number Cornwall Community Police Service P.O. Box 875 Telephone: (613) 933‐5000 www.cornwallpolice.com 340 Pitt Street Facsimile: (613) 932‐9317 Cornwall ON K6H 5T7 Deep River Police Service P.O. -

BLM 1999-04.Pdf

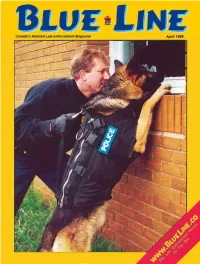

Flying Cross Command® uniform garments are For a free catalogue of all the quality Flying Cross by woven with a breathable polyester fabric that resists Fechheimer garments, just call Tricia Rudy Enterprises, stains, is machine washable, and never needs ironing. Inc., Kettleby, Ontario at 905-726-4404 or Fechheimer Command® Shirt Imodel 85R7886Z1 is form-fiHed at 1-800-543-1939. and has military dress style detailing with a 7-buHon Visit our web site at www.fechheimer.com placket front, permanent collar stays, and double-stitched shoulder straps and pocket flaps. Coordinated 100% Dacron® Polyester Trousers Imodel 39001 are available in a wide variety of colors FLYING CROSS and weaves to suit your specifications and climate. Each BY FECHHEIM R pair is made with a BanRoI® waistband and rubberized Snug-T eX® strips to prevent shirt pull out. Wear It With Pride. Volume 11 Number 4 ~.Ii.~ April 1999 - Editor I Publisher Publisher 's Commentary 5 Morley S . Lymburner New body armour ta kes 6 Phone (905) 640·3048 . Fax (905) 640·7547 canine policing by storm E-mail: [email protected] K9 Storm body armour is the world's Web Page: www.blueline.ca jirst custom jitted vest for police - News Editor - dogs. The Kevlar vest meets the Blair McQuillan Threat Level Ii Standard. General Manager Mary K. Lymburner, M.Ed. Barrie Police Headquarters 10 - Advertising - From dream to a reality Mary Lymburner (Director) Phone (905) 640-3048 Fax (905) 640-7547 Emerging Technologies 14 Bob Murray The Canadian Police Research Centre Phone (905) 640-6506 Fax (905) 642-0900 presents 7 companies displaying new and - Illustration - innovative police technology at Response 99. -

Labour and Public Health Official Contacts.Pdf

REGIONAL CONTACTS Public Health Unit Labour Regional Director Labour Program/District Manager Police Contact PHU Contact Algoma Public Health Margaret Cernigoj Jervis Bonnick Sault Ste. Marie Police Service Dr. Jennifer Loo [email protected] [email protected] Inspector Mike Davey [email protected] Office: 807-475-1622 Office: 705-945-5990 [email protected] Cell: 807-629-9808 Cell: 705-989-6258 Address: 580 Second Line East Sault Ste. Marie, ON, P6B 4K1 Phone: 705-949-6300 (ext. 198) Cell: 705-254-8896 Brant County Health Jeff McInnis Heather Leask Brantford Police Service Joann Tober Unit [email protected] [email protected] Inspector Kevin Reeder [email protected] Cell: 519-319-2156 Cell: 289-439-8152 [email protected] Address: 344 Elgin St. Robert Hall Brantford, ON, N3S 7P5 [email protected] Phone: 519-756-0113 (ext. 2309) Chatham-Kent Public Jeff McInnis Barry Norton Chatham-Kent Police Service April Rietdyk Health [email protected] [email protected] Danya Lunn [email protected] Cell: 519-319-2156 Cell: 519-791-7549 [email protected] Address: 24 Third Street Teresa Bendo P.O. Box 366 [email protected] Chatham, ON, N7M 5K5 Phone: 519-436-6600 (ext. 240) Woodstock Police Service Chief Daryl Longworth [email protected] Address: 615 Dundas St. Woodstock, ON, N4S 1E1 Phone: 519-421-2800 (ext. 2231) For Reference Purposes November 2020 1 Public Health Unit Labour Regional Director Labour Program/District Manager Police Contact PHU Contact -

Barrie Police 2019 Annual Report.Indd

BARRIE POLICE SERVICE 2019 ANNUAL REPORT VISION Policing excellence to ensure a safe and secure community. MISSION To enhance our community by providing professional, accountable and sustainable policing services. VALUES Through our actions and dedication, we model the principles of: Professionalism, Respect, Integrity, Diversity and Excellence. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 INTRODUCTION 05 INVESTIGATIVE SERVICES Vision, Mission & Values 02 Highlights 24 Table of Contents 03 Victim Supports 26 Message from the Board Chair 04 Canadian Framework For Collaborative 27 Police Response on Sexual Violence Message from the Chief of Police 05 Organizational Chart 06 Joint & Internal Forces Operations 28 02 CORPORATE 06 RECORDS & INFORMATION COMMUNICATIONS MANAGEMENT SERVICES Community Events 08 Highlights 31 Chief’s Gala 10 Social Media 12 07 HUMAN RESOURCES 03 OPERATIONAL SERVICES Highlights 32 Personnel & Training 33 Highlights 14 Awards Night 34 Community Outreach And Support Team 15 Auxiliary 16 08 EXECUTIVE SERVICES 04 OPERATIONAL SUPPORT Highlights 35 Evidence-Based Working Group 36 Tactical Support 17 Digital Evidence Management System 37 K9 Highlights 18 Strategic Business Plan Accomplishments 38 Traffic 19 Community Safety Survey Results 39 Marine 20 Statistical Highlights 40 Remotely Piloted Aircraft System 21 Professional Standards & Risk Management 42 Schools Unit 22 Junior Constable Camp 23 3 MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD CHAIR successes and identified areas for improvements when developing our new 2020-2022 Strategic Plan. On behalf of the entire Board, I want to thank our partners who helped us achieve our five key priorities of: • Ensuring Public Safety and Security • Enhancing Community Mobilization and Engagement • Developing and Engaging Our People • Promoting Organizational Sustainability • Delivering Quality Service The Annual Report illustrates how these priorities were achieved and reveals how our organization works together to accomplish a shared vision of policing excellence to ensure a safe and secure community. -

Ialep Exchange Volume 3 Fall 2017

http://www.IALEP.org IALEP EXCHANGE VOLUME 3 FALL 2017 Executive Board President William Werner Fuquay-Varina N.C. “The Other Side” Video Series St. Louis Metro Police Laura Fahnestock, Chief of Police, Town of Fuquay-Varina, N.C.,USA Department, St. Louis, Missouri, US Executive Vice President Teresa Bowling Wouldn’t it be nice if we all just talked? Columbus Division of Police Columbus, Ohio, US That was the concept behind a video Staff Vice President series that Amazing Studios, Inc. Margaret Gloade Waterloo Regional Police Service proposed to me in October of 2016. Waterloo, On, CA The video series, entitled “The Other Past President Side” would pair children from Mark Carpenter Glendale Police Department elementary school through high school Glendale, Arizona, US with a Fuquay-Varina, North Carolina Secretary Marcia M. Garcia Cunningham police officer for an intimate Albuquerque Police Department Albuquerque, New Mexico conversation about life, greatest fears, and tough decisions. The series would prompt Treasurer personal human-to-human conversations and seek to foster an overall understanding Will Davis Scottsdale Police about people – law enforcement officers and children – within the Town of Scottsdale, Arizona, US Fuquay-Varina. With the ongoing issues throughout our nation involving the division Repository Director Todd Stoker between the public and law enforcement, “The Other Side” series would allow both Kansas City Police, sides to share his or her perspective, unrehearsed and “real”, on important topics. Kansas City, Missouri, US Training & Certification Coordinator— Barry Horrobin It was a risk to participate in this type of program, which exposes levels of vulnerability Windsor Police, Windsor, ON, CA of officers and his or her life. -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. ANNOUNCING NEW EDITION OF ADMISSIBILITY OF STATEMENTS - 2013 Police Edition by The Honourable René J. Marin, CM, OMM, OOnt. Q.C., J.D., CD LLD Inside you'll learn about: • Persons in authority • Detention and arrest • Inducements • Video/audio recording of statements • After-the-fact evidence • The right to counsel • Disclosure • Reasonable expectation of privacy • Jailhouse confessions • The polygraph • Prior inconsistent statements • Confirming confessions NEW IN THIE EDITION The new, 2013 Police Edition thoroughly reviews and updates all the significant devel- opments in this area of law since the last edition, including: • Police deception • Mr. -

Information on How to Become a Police Officer Because You Asked

MO NE Y B A C K Message from the Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police Individuals considering career choices today have many options. Choosing policing opens the door to a challenging and fulfilling future. Our police services are always looking for highly qualified and motivated people from different backgrounds to join them as policing professionals. As Ontario’s police leaders, we believe that the citizens we serve deserve police professionals who are among the best and brightest from all of our communities. Whether you’re a young person just starting to look at your career options, an individual considering a career change, or someone who wants to make a positive impact in your community, policing could be an excellent choice for you. To help you discover policing, we’ve put together this informational booklet. Because of the varied nature of police work, individuals who work in law enforcement can apply the skills and experiences they’ve developed from their previous training, education, professional, and personal life in a variety of areas. Policing offers opportunities for personal growth, continuous learning, a high level of job satisfaction, opportunities for specialization, opportunities for promotion as well as excellent salary, benefits, and pension. Today’s police recruits must bring with them a high degree of comfort with modern technology, a willingness to engage members of our diverse communities, and a dedication to serving in a professional and accountable manner. A police officer must bring understanding and empathy to dealing with tough circumstances, yet always be committed to seeing justice done. This takes dedication and courage, honesty and personal integrity. -

CRIME PREVENTION 2019 YOU ARE CRIME PREVENTION HON OAPC Ad 2017 OAPC 17-02-02 11:09 AM Page 1

CRIME PREVENTION 2019 YOU ARE CRIME PREVENTION HON_OAPC Ad 2017_OAPC 17-02-02 11:09 AM Page 1 BE AWARE OF SUSPICIOUS ACTIVITY Hydro One is calling on all citizens for their help in ensuring their own personal security as well as the safeguarding of Hydro One assets. We are seeking the eyes and ears of the community to be on the lookout for signs of suspicious activity near our stations and facilities and report any such activity to police immediately. HYDRO ONE ASSETS ARE MARKED WITH TRACE™ MICRODOTS www.HydroOne.com Partners in Powerful Communities A MESSAGE FROM THE ONTARIO ASSOCIATION OF CHIEFS OF POLICE Protecting your personal safety and that of your loved ones, friends, and co-workers should be a high priority for everyone who lives and works in our great Province. By doing your part in preventing crime, you are promoting your own quality-of-life as well as your community’s well-being and safety. Ontario’s Police Services and all our law enforcement personnel make Crime Prevention a critical part of what they do. Our people work hard to meet the expectations of the citizens they serve. While the public safety focus and priorities may change, our commitment to preventing crime before we have to deal with the consequences of crime remains constant. The 2019 OACP Crime Prevention Campaign focuses on the fact that “You Are Crime Prevention.” In this booklet you will find helpful tips on many issues, including: • Community safety is a shared responsibility, starting with every individual; • Legal cannabis – making sure you make the right choice when it comes to both medical and recreational cannabis; • Making sure that we stop distracted driving in its tracks; • Protecting yourself from cybercrime, on-line scams, identity theft; and, • Ensuring you are not a victim of auto-insurance fraud. -

POLICE WORKING AGREEMENT Between the BARRIE

POLICE WORKING AGREEMENT Between THE BARRIE POLICE SERVICES BOARD (hereinafter referred to as “the Board”) OF THE FIRST PART And THE BARRIE POLICE ASSOCIATION (hereinafter referred to as “the Association”) OF THE SECOND PART JANUARY 1, 2019 TO DECEMBER 31, 2023 1 Contents 1.0 DEFINITIONS ......................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 ARTICLE 2 – PURPOSE .......................................................................................................... 4 3.0 ARTICLE 3 – RECOGNITION .................................................................................................. 4 4.0 ARTICLE 4 – MANAGEMENT RIGHTS .................................................................................... 4 5.0 ARTICLE 5 – ASSOCIATION RIGHTS ...................................................................................... 5 6.0 ARTICLE 6 – SALARIES .......................................................................................................... 6 7.0 ARTICLE 7 – HOURS OF WORK ............................................................................................. 6 8.0 ARTICLE 8 – OVERTIME ........................................................................................................ 9 9.0 ARTICLE 9 – OUT OF TOWN ASSIGNMENTS ....................................................................... 12 10.0 ARTICLE 10 – JOB POSTINGS, PROMOTIONS AND EVALUATIONS ..................................... 13 11.0 ARTICLE 11 – PLAINCLOTHES DUTY