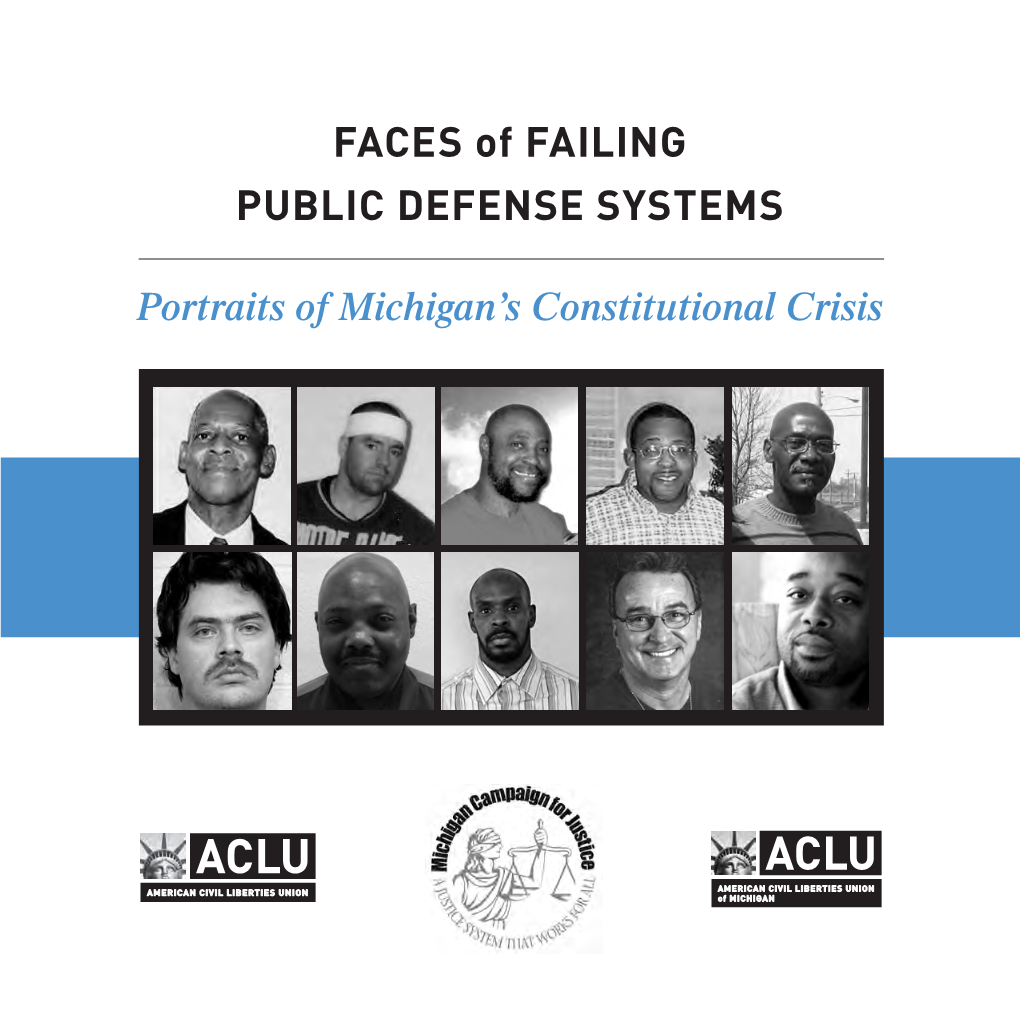

FACES of FAILING PUBLIC DEFENSE SYSTEMS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Template EUROVISION 2021

Write the names of the players in the boxes 1 to 4 (if there are more, print several times) - Cross out the countries that have not reached the final - Vote with values from 1 to 12, or any others that you agree - Make the sum of votes in the "TOTAL" column - The player who has given the highest score to the winning country will win, and in case of a tie, to the following - Check if summing your votes you’ve given the highest score to the winning country. GOOD LUCK! 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Anxhela Peristeri “Karma” Albania Montaigne “ Technicolour” Australia Vincent Bueno “Amen” Austria Efendi “Mata Hari” Azerbaijan Hooverphonic “ The Wrong Place” Belgium Victoria “Growing Up is Getting Old” Bulgaria Albina “Tick Tock” Croatia Elena Tsagkrinou “El diablo” Cyprus Benny Christo “ Omaga “ Czech Fyr & Flamme “Øve os på hinanden” Denmark Uku Suviste “The lucky one” Estonia Blind Channel “Dark Side” Finland Barbara Pravi “Voilà” France Tornike Kipiani “You” Georgia Jendrick “I Don’t Feel Hate” Germany Stefania “Last Dance” Greece Daði og Gagnamagnið “10 Years” Island Leslie Roy “ Maps ” Irland Eden Alene “Set Me Free” Israel 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Maneskin “Zitti e buoni” Italy Samantha Tina “The Moon Is Rising” Latvia The Roop “Discoteque” Lithuania Destiny “Je me casse” Malta Natalia Gordienko “ Sugar ” Moldova Vasil “Here I Stand” Macedonia Tix “Fallen Angel” Norwey RAFAL “The Ride” Poland The Black Mamba “Love is on my side” Portugal Roxen “ Amnesia “ Romania Manizha “Russian Woman” Russia Senhit “ Adrenalina “ San Marino Hurricane “LOCO LOCO” Serbia Ana Soklic “Amen” Slovenia Blas Cantó “Voy a quedarme” Spain Tusse “ Voices “ Sweden Gjon’s Tears “Tout L’Univers” Switzerland Jeangu Macrooy “ Birth of a new age” The Netherlands Go_A ‘Shum’ Ukraine James Newman “ Embers “ United Kingdom. -

The Tragic Muse, by Henry James 1

The Tragic Muse, by Henry James 1 The Tragic Muse, by Henry James The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Tragic Muse, by Henry James This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Tragic Muse Author: Henry James Release Date: December 10, 2006 [eBook #20085] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 The Tragic Muse, by Henry James 2 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TRAGIC MUSE*** E-text prepared by Chuck Greif, R. Cedron, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team Europe (http://dp.rastko.net/) THE TRAGIC MUSE by HENRY JAMES MacMillan and Co., Limited St. Martin's Street, London 1921 PREFACE I profess a certain vagueness of remembrance in respect to the origin and growth of The Tragic Muse, which appeared in the Atlantic Monthly again, beginning January 1889 and running on, inordinately, several months beyond its proper twelve. If it be ever of interest and profit to put one's finger on the productive germ of a work of art, and if in fact a lucid account of any such work involves that prime identification, I can but look on the present fiction as a poor fatherless and motherless, a sort of unregistered and unacknowledged birth. I fail to recover my precious first moment of consciousness of the idea to which it was to give form; to recognise in it--as I like to do in general--the effect of some particular sharp impression or concussion. -

V STATE of MICHIGAN SUMMONS CASE NO. Instructions

Original - Court 2nd copy - Plaintiff Approved, SCAO 1st copy - Defendant 3rd copy - Return STATE OF MICHIGAN CASE NO. JUDICIAL DISTRICT JUDICIAL CIRCUIT SUMMONS 2018 MZ COUNTY PROBATE Court address Court telephone no. Court of Claims, Hall of Justice, 925 W. Ottawa Street, Lansing, MI 48909 (517) 373-0807 Plaintiff’s name(s), address(es), and telephone no(s). Defendant’s name(s), address(es), and telephone no(s). OAKLAND COUNTY WATER RESOURCES MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL COMMISSIONER, as County Agent for the County of Oakland, QUALITY GREAT LAKES WATER AUTHORITY, v CITY OF DETROIT, by and through its Water and Sewerage Department, AND CITY OF LIVONIA Plaintiff’s attorney, bar no., address, and telephone no. Peter H. Webster (P48783), Dickinson Wright PLLC, 2600 W. Big Beaver, Ste. 300, Troy, MI 48084, (248) 433-7200; Steven E. Chester (P32984), Miller, Canfield, Paddock and Stone, PLC, One Michigan Bldg., 120 N. Washington Sq., Ste. 900, Lansing, MI 48933, (517) 483-4933; Randal Brown (P70031), 735 Randolph, Ste. 1900, Detroit, MI 48226, (313) 964-9068; Michael Fisher (P37037), 33000 Civic Center Drive, Livonia, MI 48154, (734) 466-2520 Instructions: Check the items below that apply to you and provide any required information. Submit this form to the court clerk along with your complaint and, if necessary, a case inventory addendum (form MC 21). The summons section will be completed by the court clerk. Domestic Relations Case There are no pending or resolved cases within the jurisdiction of the family division of the circuit court involving the family or family members of the person(s) who are the subject of the complaint. -

Sermon Notes

The Resurrection Of Christ (With A Message To Seekers) Mark 15:40-16:8 Right now, our four-year old grandson, Calvin, likes to play hide and go seek, as does his 2 ½ year-old sister Margo. Each game seems to take longer than expected. Their hearts are in the right place, they are eager to play the game, but they don’t look in right places (and they can get a bit sidetracked) so it takes a while. Sometimes I have to make noises to redirect them to where I’m at. We are going to see something similar in the passage today; those whose hearts that are in the right place, but as they seek Jesus, He isn’t where they are looking. The passage this morning is the account of Jesus’ resurrection from the dead. And when the women who have come to anoint His body with spices get to His tomb, He isn’t there. And if we were reading Luke, the angel at His tomb will ask these devoted followers, “Why are you seeking the living, among the dead?” “You’re looking in the wrong place.” The word seek is used throughout the Scriptures to describe a pursuit of something we desire, whether it’s good for us or not. For instance, the bride in the Song of Solomon says this in 3:2. “I must arise now and go about the city; in the streets and in the plazas. I must seek him whom my soul loves. I sought him but did not find him.” I don’t she gave up. -

Home Fire : a Novel / Kamila Shamsie

Also by Kamila Shamsie In the City by the Sea Salt and Saffron Kartography Broken Verses Burnt Shadows A God in Every Stone RIVERHEAD BOOKS An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC 375 Hudson Street New York, New York 10014 Copyright © 2017 by Kamila Shamsie Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Shamsie, Kamila [date], author. Title: Home fire : a novel / Kamila Shamsie. Description: New York : Riverhead Books, 2017. Identifiers: LCCN 2017003238 | ISBN 9780735217683 (hardcover) Subjects: LCSH: Families—Fiction. | Domestic fiction. | Political fiction. | BISAC: FICTION / Family Life. | FICTION / Political. | FICTION / Cultural Heritage. | GSAFD: Love stories. Classification: LCC PR9540.9.S485 H66 2017 | DDC 823/.914—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017003238 p. cm. Ebook ISBN: 9780735217706 This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Version_1 For Gillian Slovo Contents Also by Kamila Shamsie Title Page Copyright Dedication Epigraph Isma Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Eamonn Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Parvaiz Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Aneeka Chapter 7 Karamat Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Acknowledgments About the Author The ones we love . -

Coming to Watervliet Twp. Industrial Park

I Coming to Watervliet Twp. Industrial Park $ 80 million gas plant means 350 jobs On Thursday, May 11, Berrien employ at least 50 people once it is use it intends to process 20 million have anymore information than was about the location and the area sur- Watervliet Township, the City of County Brown field Authority appr- operational. The economic impact of bushels of com annually into etha- released at this time. rounding their proposed new site. Watervliet, and the Coloma Water- oved the sale of 34 acres of land in this plant could generate an addi- nol. County Commissioner Victoria Township resident Bob Becker vliet Economic Development Corp- the Watervliet Red Arrow Industrial tional 300 jobs in the local agricul- "What's not to like Chandler told the audience that summed it up, "Why not this com- oration (CWAEDC). Park to NextGen Energy LLC, an tural and service sectors. future public hearings would be held munity? We have close proximity to Six years ago, the Brownfield about Watervliet?" ethanol production company out of The company indicated that it by NextGen that would, hopefully, 1-94, the rail service is right there, Authority acquired the property Southfield, MI. NextGen intends to selected this location because of the As expected, the discussion of this answer all questions and take care of and what's not to like about Water- after the closure of the Fletcher construct and operate a 50-million- park's established infrastructure, rail recent development came up at the any concerns. vliet?" Paper mill in Watervliet. Through its gallon-per-year ethanol production access, proximity to 1-94, and avail- Watervliet Township Board meeting When questions arose about why The Watervliet Red Arrow Indus- partnership with the state, the plant within the park. -

Daughters May Spark Jump Start's Legacy

THURSDAY, MAY 23, 2019 DAUGHTERS MAY SPARK PET AND MRI: A BRAVE NEW DIAGNOSTIC WORLD by Dan Ross JUMP START'S LEGACY Earlier this month, The Stronach Group announced the arrival later this year at Santa Anita of the Longmile Positron Emission Tomography (MILE-PET) Scan machine--a technology currently under development at California's UC Davis, that could revolutionize the diagnosis of emerging lower limb injuries that could deteriorate into something catastrophic. But Santa Anita's new PET scan machine might not be the only important development at the track. According to CHRB equine medical director Rick Arthur, efforts are afoot to possibly bring a standing MRI to Santa Anita. The MRI machine's possible arrival raises some interesting tensions between the two diagnostic modalities. Indeed, proponents of both technologies argue passionately about their individual merits in early injury detection. But what isn't up for debate is how they both present a win for the horse. Cont. p5 Jump Start | Northview Stallion Station by Chris McGrath IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Here's a hunch, even a wager if you care to stick around long enough. Because I wouldn't be at all surprised should we SHAMARDAL A SIRE OF THE HIGHEST CLASS someday notice the damsire of a new champion and remember, John Boyce examines the stud career of Shamardal, who has made a strong start to 2019. with a smile, the splendid Jump Start. Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. Pennsylvanian breeders won't need telling what a dynamo among stallions they lost on Sunday. -

Fence Above the Sea Brigitte Byrd

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 Fence Above the Sea Brigitte Byrd Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FENCE ABOVE THE SEA Name: Brigitte Byrd Department: English Major Professor: David Kirby Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Term Degree Awarded: Summer, 2003 “Fence above the Sea” is a collection of prose poems written in sequences. Writing in the line of Emily Dickinson, Gertrude Stein, and Lynn Hejinian, I experiment with language and challenge its convention. While Dickinson writes about “the landscape of the soul,” I write about the landscape of the mind. While she appropriates and juxtaposes words in a strange fashion, I juxtapose fragments of sentences in a strange fashion. While she uses dashes to display silence, I discard punctuation, which is disruptive and limits the reader to a set reading of the sentence. Except for the period. Stein’s writing is the epitome of Schklovsky’s concept of ostranenie (defamiliarization). Like her poems in Tender Buttons, my poems present a multiplied perspective. On the moment. Like Stein, I write dialogical poems where there is a dialogue among words and between words and their meanings. Also, I expect a dialogue between words and readers, author and readers, text and readers. My prose poems focus on sentences “with a balance of their own. the balance of space completely not filled but created by something moving as moving is not as moving should be” (Stein, “Poetry and Grammar”). Repetitions are essential in everyday life, to the thought process, and thus in this collection. -

If You Have Issues Viewing Or Accessing This File Contact Us at NCJRS.Gov

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. I I -tJ• I " - -r, T __ : -~ :. ... -!I.o _ • - _:. .. I -- - .. .. .~ ~ f • # 1 LEAA Activities July 1,1969 to June 30,1970 Law Enforcement Assistance Administration U.S. Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530 146878 U.S. Department of Jus!lce National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the (lfficlal position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this DP 'gI "" material has been gr~~t~ic Domain/LEAA U.S. Department of Justice to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the ~ owner. For sale by the Superintendent o( Documents, U.S. Government Prlntlns Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.50 per 2 volume set. Sold In sets only. Message from the Administrators The year 1970 demonstrated that the federal-state-local government partnership represented by the block grant approach offers the most effective means of improving the criminal justice system in the United States. This approach recognizes the importance of local commitment, priorities and decision making as how best to control crime, tempered with adherence to statutory requirements of comprehensiveness, plan balance and full local involvement in the formulation and benefits of the program. Some problems have arisen-some states and local units of government resent any direction from Washington-such as our emphasis on ccirrer.t,ions improvement in fiscal 1970. -

Tributaries on the Name of the Journal: “Alabama’S Waterways Intersect Its Folk- Ways at Every Level

Tributaries On the name of the journal: “Alabama’s waterways intersect its folk- ways at every level. Early settlement and cultural diffusion conformed to drainage patterns. The Coastal Plain, the Black Belt, the Foothills, and the Tennessee Valley re- main distinct traditional as well as economic regions today. The state’s cultural landscape, like its physical one, features a network of “tributaries” rather than a single dominant mainstream.” —Jim Carnes, from the Premiere Issue JournalTributaries of the Alabama Folklife Association Joey Brackner Editor 2002 Copyright 2002 by the Alabama Folklife Association. All Rights Reserved. Issue No. 5 in this Series. ISBN 0-9672672-4-2 Published for the Alabama Folklife Association by NewSouth Books, Montgomery, Alabama, with support from the Folklife Program of the Alabama State Council on the Arts. The Alabama Folklife Association c/o The Alabama Center for Traditional Culture 410 N. Hull Street Montgomery, AL 36104 Kern Jackson Al Thomas President Treasurer Joyce Cauthen Executive Director Contents Editor’s Note ................................................................................... 7 The Life and Death of Pioneer Bluesman Butler “String Beans” May: “Been Here, Made His Quick Duck, And Got Away” .......... Doug Seroff and Lynn Abbott 9 Butler County Blues ................................................... Kevin Nutt 49 Tracking Down a Legend: The “Jaybird” Coleman Story ................James Patrick Cather 62 A Life of the Blues .............................................. Willie Earl King 69 Livingston, Alabama, Blues:The Significance of Vera Ward Hall ................................. Jerrilyn McGregory 72 A Blues Photo Essay ................................................. Axel Küstner Insert A Vera Hall Discography ...... Steve Grauberger and Kevin Nutt 82 Chasing John Henry in Alabama and Mississippi: A Personal Memoir of Work in Progress .................John Garst 92 Recording Review ........................................................ -

1 All in God's Family a Full Length Play

1 ALL IN GOD’S FAMILY A FULL LENGTH PLAY BY BRUCE HENNIGAN Copyright © APRIL, 2000 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CAST: LUCY- Loud and intruding THELMA – Quieter and a bit “ditzy” DIXIE – Southern Belle NORTON MORTON – A bit dense. VINNY MORTON – A bit denser MONA DOUGLAS – A true “floozy” dressed in tight, garish clothing with lots of big hair ( a wig) and huge dangly earrings MOM – Vinny’s mother ala Golden Girls with huge glasses on gold chains, beehive hair do and wearing a sweater over her shoulders. ROCKY BARTON – Think of Archie Bunker BLANCHE BARTON – Think of Edith Bunker, only with less upstairs JEFFY BARTON – Teenage son played pretty straight NOTE: All cast should try to use a New York accent. STAGE: Very simple with two “wingback” chairs stage right and a small dining table with three chairs stage left. For the bowling alley scene, just remove the table and chairs and leave the stage bare. This play is written to be performed in “theater in the round” fashion with very few stage props. 2 SCENE 1 (ROCKY COMES OUT ON STAGE AND ADDRESSES THE AUDIENCE. HE WILL USE THIS TECHNIQUE THROUGHOUT THE PLAY, ALLOWING SCENE CHANGES TO OCCUR BEHIND HIM.) ROCKY: Rocky Barton, here. This is my house and in a minute, there, you’re going to meet my wife, Blanche. Blanche is, well, she is, Blanche, you know. And there’s her two friends Lucy and Thelma. They remind me of a one story building – nothing upstairs, if you know what I mean. And, they like to stick their noses where they don’t belong, there. -

2017 Violent and Property Crimes by County, City/Township

2017 Violent and Property Crimes by County, City/Township Data as of: March 15, 2018 Motor Agg. Violent Vehicle Property Index Non‐Index Total County and City/Township Murder Rape Robbery Assaults Crime Burglary Larceny The Crime Arson Crimes Crimes Crimes Alcona 0 7 1 715 38 85 5 1282 145 413 558 Alcona Township 00 0 006 4 2027 0 621 Caledonia Township 01 0 0115 2 12147 016 31 Curs Township 00 0 2217 7 8267 019 48 Greenbush Township 00 1 0116 0 16074 118 56 Gusn Township 01 0 017 2 5042 0 834 Harrisville 01 0 1210 2 8056 012 44 Harrisville Township 00 0 227 1 6049 110 39 Hawes Township 00 0 006 2 3138 0 632 Haynes Township 01 0 014 1 2123 0 518 Lincoln 01 0 016 2 4031 0 724 Mikado Township 01 0 019 3 6052 010 42 Millen Township 00 0 114 1 3018 0 513 Mitchell Township 0 1 0 1221 11 10034 0 23 11 Alger 17 01422 26493 780 100 390 490 Alger Co Maximum Correconal Facility 11 0 350 0 0019 0 514 Au Train Township 01 0 237 3 4048 010 38 Burt Township 01 0 013 2 1015 0 411 Chatham 00 0 111 0 106 0 24 Grand Island Township 00 0 000 0 007 0 07 Limestone Township 02 0 024 3 019 0 63 Mathias Township 00 0 445 2 2126 0 917 Munising 02 0 3546 8 371 051 204 255 Munising Township 00 0 1110 6 4084 011 73 Onota Township 00 0 001 1 005 0 14 Rock River Township 00 0 001 1 0016 0 115 Allegan 1 83 7 121212 267 977 85 1,32911 1,552 7,465 9,017 Allegan 04 0 913 3 842 89 1103 709 812 Allegan Township 0 1 0 4556 10 442 0 61 300 361 Casco Township 1 3 0 2631 11 164 1 38 170 208 Cheshire Township 0 1 0 5635 11 222 0 41 156 197 Clyde Township 02 0 3517 4 112 022 125 147 Violent/Property Crimes by City/Township Page 1 of 63 2017 Crime in Michigan 2017 Violent and Property Crimes by County, City/Township Data as of: March 15, 2018 Motor Agg.