V STATE of MICHIGAN SUMMONS CASE NO. Instructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coming to Watervliet Twp. Industrial Park

I Coming to Watervliet Twp. Industrial Park $ 80 million gas plant means 350 jobs On Thursday, May 11, Berrien employ at least 50 people once it is use it intends to process 20 million have anymore information than was about the location and the area sur- Watervliet Township, the City of County Brown field Authority appr- operational. The economic impact of bushels of com annually into etha- released at this time. rounding their proposed new site. Watervliet, and the Coloma Water- oved the sale of 34 acres of land in this plant could generate an addi- nol. County Commissioner Victoria Township resident Bob Becker vliet Economic Development Corp- the Watervliet Red Arrow Industrial tional 300 jobs in the local agricul- "What's not to like Chandler told the audience that summed it up, "Why not this com- oration (CWAEDC). Park to NextGen Energy LLC, an tural and service sectors. future public hearings would be held munity? We have close proximity to Six years ago, the Brownfield about Watervliet?" ethanol production company out of The company indicated that it by NextGen that would, hopefully, 1-94, the rail service is right there, Authority acquired the property Southfield, MI. NextGen intends to selected this location because of the As expected, the discussion of this answer all questions and take care of and what's not to like about Water- after the closure of the Fletcher construct and operate a 50-million- park's established infrastructure, rail recent development came up at the any concerns. vliet?" Paper mill in Watervliet. Through its gallon-per-year ethanol production access, proximity to 1-94, and avail- Watervliet Township Board meeting When questions arose about why The Watervliet Red Arrow Indus- partnership with the state, the plant within the park. -

If You Have Issues Viewing Or Accessing This File Contact Us at NCJRS.Gov

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. I I -tJ• I " - -r, T __ : -~ :. ... -!I.o _ • - _:. .. I -- - .. .. .~ ~ f • # 1 LEAA Activities July 1,1969 to June 30,1970 Law Enforcement Assistance Administration U.S. Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530 146878 U.S. Department of Jus!lce National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the (lfficlal position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this DP 'gI "" material has been gr~~t~ic Domain/LEAA U.S. Department of Justice to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the ~ owner. For sale by the Superintendent o( Documents, U.S. Government Prlntlns Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.50 per 2 volume set. Sold In sets only. Message from the Administrators The year 1970 demonstrated that the federal-state-local government partnership represented by the block grant approach offers the most effective means of improving the criminal justice system in the United States. This approach recognizes the importance of local commitment, priorities and decision making as how best to control crime, tempered with adherence to statutory requirements of comprehensiveness, plan balance and full local involvement in the formulation and benefits of the program. Some problems have arisen-some states and local units of government resent any direction from Washington-such as our emphasis on ccirrer.t,ions improvement in fiscal 1970. -

2017 Violent and Property Crimes by County, City/Township

2017 Violent and Property Crimes by County, City/Township Data as of: March 15, 2018 Motor Agg. Violent Vehicle Property Index Non‐Index Total County and City/Township Murder Rape Robbery Assaults Crime Burglary Larceny The Crime Arson Crimes Crimes Crimes Alcona 0 7 1 715 38 85 5 1282 145 413 558 Alcona Township 00 0 006 4 2027 0 621 Caledonia Township 01 0 0115 2 12147 016 31 Curs Township 00 0 2217 7 8267 019 48 Greenbush Township 00 1 0116 0 16074 118 56 Gusn Township 01 0 017 2 5042 0 834 Harrisville 01 0 1210 2 8056 012 44 Harrisville Township 00 0 227 1 6049 110 39 Hawes Township 00 0 006 2 3138 0 632 Haynes Township 01 0 014 1 2123 0 518 Lincoln 01 0 016 2 4031 0 724 Mikado Township 01 0 019 3 6052 010 42 Millen Township 00 0 114 1 3018 0 513 Mitchell Township 0 1 0 1221 11 10034 0 23 11 Alger 17 01422 26493 780 100 390 490 Alger Co Maximum Correconal Facility 11 0 350 0 0019 0 514 Au Train Township 01 0 237 3 4048 010 38 Burt Township 01 0 013 2 1015 0 411 Chatham 00 0 111 0 106 0 24 Grand Island Township 00 0 000 0 007 0 07 Limestone Township 02 0 024 3 019 0 63 Mathias Township 00 0 445 2 2126 0 917 Munising 02 0 3546 8 371 051 204 255 Munising Township 00 0 1110 6 4084 011 73 Onota Township 00 0 001 1 005 0 14 Rock River Township 00 0 001 1 0016 0 115 Allegan 1 83 7 121212 267 977 85 1,32911 1,552 7,465 9,017 Allegan 04 0 913 3 842 89 1103 709 812 Allegan Township 0 1 0 4556 10 442 0 61 300 361 Casco Township 1 3 0 2631 11 164 1 38 170 208 Cheshire Township 0 1 0 5635 11 222 0 41 156 197 Clyde Township 02 0 3517 4 112 022 125 147 Violent/Property Crimes by City/Township Page 1 of 63 2017 Crime in Michigan 2017 Violent and Property Crimes by County, City/Township Data as of: March 15, 2018 Motor Agg. -

Hate Crime in Michigan

HATE CRIME IN MICHIGAN Definition: Hate Crime is a criminal offense committed against a person or property which is motivated in whole or in part, by the offender’s bias against a race/national origin, religion, sexual-orientation, mental/physical disability or ethnicity - Victim Information Victim Type Business 70 Government 16 Hate crime incidents are identified on the motivation of the offender(s). Law Individual 744 enforcement investigations determine the objective facts to lead to a reasonable Other 5 conclusion that the offender’s actions were motivated by bias against a racial, religious, Police Officer 5 ethnic/national origin, mental/physical disability, or sexual-orientation group. Accurate data collection of hate crimes depends heavily on proper training of law enforcement to Religious Organization 5 recognize such incidents and the cooperation and desire of communities/victims to Society/Public 67 report these incidents to law enforcement. Unknown 2 Grand Total 914 Victims by Type Unknown 2 Society/Public 67 A total of 914 victims of hate crimes were reported to the UCR unit in 2007. Religious Organization 5 Individuals and police officers made up 749 of those totals. Police Officer 5 Other 5 According to the statistics, you are more 744 likely to become a victim of a hate crime if Individual you are between the age 10 and 19. Anti- black was the most targeted bias for all Government 16 the age groups. Business 70 1 10 100 1000 2007 MICHIGAN INCIDENT CRIME REPORT HATE CRIME IN MICHIGAN Victims by Age Group and Bias Motivation Totals by Bias Motivation Totals Anti-Am. -

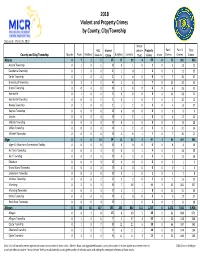

SAP Crystal Reports

2018 Violent and Property Crimes by County, City/Township Data as of: March 25, 2019 Motor Agg. Violent Vehicle Property Part I Part II Total County and City/Township Murder Rape Robbery Assaults Crime Burglary Larceny Theft Crime Arson Crimes Crimes Crimes Alcona 0 7 1 715 17 39 4 60 0 75 281 356 Alcona Township 01 0 121 0 1021 0 318 Caledonia Township 01 0 012 1 0115 0 312 Curtis Township 01 0 016 2 4037 0 730 Greenbush Township 02 1 147 2 4133 01122 Gustin Township 00 0 006 2 4031 0 625 Harrisville 01 0 459 0 9072 01458 Harrisville Township 00 0 111 0 1022 0 220 Hawes Township 01 0 013 1 2017 0 413 Haynes Township 00 0 000 0 006 0 0 6 Lincoln 00 0 006 2 3123 0 617 Mikado Township 00 0 009 4 5028 0 919 Millen Township 00 0 003 1 2024 0 321 Mitchell Township 00 0 007 2 4127 0 720 Alger 05 01924 12523 67 3 94 467 561 Alger Co Maximum Correctional Facility 00 0 880 0 0016 0 8 8 Au Train Township 00 0 334 0 3155 0 748 Burt Township 00 0 003 0 3016 0 313 Chatham 00 0 000 0 001 0 0 1 Grand Island Township 00 0 000 0 005 0 0 5 Limestone Township 00 0 001 0 108 0 1 7 Mathias Township 00 0 225 2 3022 0 715 Munising 0 5 0 3844 7 361 3 55 282 337 Munising Township 00 0 338 2 5166 01155 Onota Township 00 0 000 0 0017 0 017 Rock River Township 00 0 002 1 1018 0 216 Allegan 0 83 10 167260 235 860 115 1,210 6 1,476 7,432 8,908 Allegan 0 6 1 815 4 395 48 0 63 608 671 Allegan Township 0 1 0 6743 2 374 0 50 318 368 Casco Township 0 1 0 7838 12 215 0 46 197 243 Cheshire Township 0 1 0 1218 6 111 0 20 144 164 Clyde Township 0 2 0 4625 11 113 0 31 109 140 Data is for all law enforcement agencies who can report crimes for these cities. -

CRIME E- MICHIGAN

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. \ ~." 'f..- .... CRIME MICHIGAN 1991 aD NIFORM CRIME " REPORT e- ~ C Compiled by rt)- DEPARTMENT OF STATE POLICE 1991 UNIFORM CRIME REPORT 137738 for i:~e U.S. Department of Justice STATE OF MICHIGAN National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official po~ition or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been gr1Jr1c~gan State Police to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRSj. Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis· sion of the copyright owner. 33rd Annual Edition MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF STATE POLICE 714 South Harrison Road i" '1 East Lansing, Michigan 48823 n 1> ':l =to COL. Michael D. Robinson, DIRECTOR £) c: I c: CD- (f !t CJ) eoi a~ j Authority: 1968 P.A.319 v:> --{ Number of copies printed - 1700 -= :lJ ~. ~ ~ ~~ Total cost of printing - $1700.00 0 .. .:j. Cost per single copy - $1.00 ,-:1 r~ Z r/( .? ill ".'{ \.Y ~ STATE OF MICHIGAN 1$ JOHN ENGLER, GOVERNOR DEPARTMENT OF STATE POLICE 714 SOUTH HARRISION ROAD, EAST LANSING, MICHIGAN 48823 COL. MICHAEL D. ROBINSON, DIRECTOR FOREWORD This constitutes the 33rd Crime In Michigan annual report prepared by the Unifonn Crime Reporting Program pursuant to PA 319 of 1968, as amended. The Department of State Police appreciates the cooperation and support of the nearly 600 police departments, sheriffs' offices, and specialized law enforcement agencies that provide offense and arrest data for the . -

For the People, by the People

H HOW STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS OPERATE For the People By the People Citizen participation is an essential component of any democratic government. Leaders require input and feedback from the public to enact policies consistent with the will of the people, but information about the public’s wishes does not always make it to the people in power. In many cases, communication between the public and their elected leaders is limited by citizens’ uncertainty about the way government operates or the most effective means of sharing information with their representatives. Knowing who is responsible for particular aspects of public policy and how to contact them is important for anyone who wants to impact the process. This booklet provides an overview of state and local governments. There is a brief description of each branch of our state government (legislative, executive, and judicial) and a brief explanation of how each branch operates. There is also an explanation of how ideas turn into bills and become laws, in addition to a glossary of common legislative terms. Another section of this booklet offers advice about how to contact your state legislator and other government officials and set your comments apart from the rest. The section on local government gives a description of local financing and explains the functions of county, city, township, and village government. It also discusses special districts and authorities and school districts in order to provide an explanation of these operations. There is also a section in the back of the booklet for you to record names, addresses, phone numbers, and email addresses of your own U.S., state, and local government officials. -

Crime Michigan

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ,- 1 ~- ,..,.~' "~~ .~,." .",~ ,"~., •. " O:~""l"'···' '. "~·-"·~(·~·"·:::·""'~~""""""'''~'~'''~-<l~··-~'·''''''''''·''""'''~'V' CRIME MICHIGAN 1993 UNIFORM CRIME REPORT Compiled by DEPARTMENT OF STATE POLICE • e • 1993 UNIFORM CRIME REPORT -:':j) for the STATE OF MICHIGAN 35th Annual Edition l" o Ch £) m MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF STATE POLICE -0 z 714 South Harrison Road ~ " East Lansing, Michigan 48823 15d189 u.s. Department of Justic;e COL. Michael D. Robinson, DIRECTOR Natlona/lnstitute of Justicv This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in Authority: 1968 P.A. 319 this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Number of copies printed - 1700 Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been Total cost oC printing - $2584.00 granted by • Cost per single copy - $1.52 Hicnigan state Pollce to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permiSSion of the copyright owner. • STATE OF MICHIGAN • •• JOHN ENGLER,- GOVERNOR DEPARTMENT OF STATE POLICE 714 SOUTH HARRISION ROAD, EAST LANSING, MICHIGAN 48823 COL. MICHAEL D. ROBINSON, DIRECTOR FOREWORD This constitutes the 35th Crime in Michigan annual report prepared by the Uniform Crime Reporting Program pursuant to PA 319 of 1968, as amended. The Department of State Police appreciates the cooperation and support of the nearly 600 police departments, sheriffs' offices, and specialized law enforcement agencies that provide offense and arrest data for the report. -

Handbook of Legal Terms

Handbook of Legal Terms Michigan Judicial Institute 925 West Ottawa Street Lansing, MI 48913 (517) 373–7171 mjieducation.mi.gov First Printing - 1977 Second Printing - 1981 Third Printing - 1989 Fourth Printing - 1993 Fifth Printing - 1995 Sixth Printing - 1996 Seventh Printing - 1999 Eighth Printing - 2002 Current Version - 2015 HANDBOOK OF LEGAL TERMS INTRODUCTION The Michigan Judicial Institute (MJI) was created in 1977 by the Michigan Supreme Court. MJI is responsible for providing educational programs and written materials for Michigan judges and court personnel. In addition to formal seminar offerings, MJI is engaged in a broad range of publication activities, services, and projects that are designed to enhance the professional skills of all those serving in the Michigan court system. The Handbook of Legal Terms is produced by the Michigan Judicial Institute to meet the needs of those employees of the court system who are not legally trained, yet work with the law and court procedures. Since this Handbook is designed for nonlegal personnel, the definitions are written in plain English rather than in complicated legal terms. The Handbook is the product of hundreds of interviews and the analysis of survey questionnaires completed by many court employees in 1976, and it has been periodically updated with the assistance of judges, SCAO staff and other court officials. It has been prepared at the request of judges, court administrators and other court supervisory personnel. The Michigan Judicial Institute wishes to thank the countless court employees who participated in the preparation of this booklet, and hopes that the Handbook will be a useful reference. This project was initially supported by a grant awarded by the Michigan Office of Criminal Justice Programs under the Crime Control Act of 1976. -

Crime in Michigan·

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. CRIME IN MICHIGAN· - ., ~ .. .. t A Report From lesidents ~ d Employers ~ 7th edition 1979 CRIME I~ MICHIGAN A REPORT FRO~1 RESIDENTS AND EMPLOYERS (7th EDITION IN AN ANNUAL SERIES) ON BEHALF OF GOVERNOR WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN AND THE MICHIGAN COMM!SSION ON CRIMINAL JUSTICE AND CONDUCTED BY MARKET OPINION RESEARCH CO. PUBLISHED MAY 1979 THIS PROJECT WAS ASSISTED BY A GRANT FROM THE LAW ENFORCEMENT ASSISTANCE ADMINISTRf\TION, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE NCJRS JUN 211979 ACQUISITIONS t NOTE This report is based on survey projects developed by the Office of Criminal Justice Programs and administered by Market Opinion Research, a national research organization headquartered in Detroit. The citizens l attitude and opinion survey is the seventh annual survey in a series. The crime incident reporting portion of the citizen survey is in its second year. The survey of employers to obtain crime incident reporting for 1978 repeats a survey conducted last year covering 1977. The large amounts of data collected in the citizen and employer surveys summarized here preclude printing of all data. Readers interested in further detail on demographic or geographic subgroups may contact: Glen Bachelder, Dr. Barbara Bryant, Director of Planning Group Vice President Office of Criminal Justice Programs Market Opinion Research 2nd Floor, Lewis Cass Building 28 West Adams Lansing, Michigan 48913 Detroit, Michigan 48226 Darnell Carr, Analyst Market Opinion Research 28 West Adams Detroit, Michigan 48226 Cover Artwork by Darsealle L. Head MARKET OPINION RESEARCH TABLE OF CQNTENTS Pages FOREWORD . ., . • • - .. • e. -

Michigan in Brief: 2002-03

Michigan in Brief: 2002–03 Michigan in Brief 2002–03 7TH EDITION Michigan Nonprofit Association Council of Michigan Foundations Prepared and published by Public Sector Consultants, Inc. © 1986, 1987, 1988, 1990, 1998, 1992, 2002 by Public Sector Consultants, Inc. All rights reserved Published 1986, Seventh Edition 2002 No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from Public Sector Consultants, Inc., 600 West St. Joseph Street, Lansing, Michigan 48933-2267, 517/484-4954, 517/484-6549 (FAX), [email protected], www.publicsectorconsultants.com Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-9721073-0-4 ABOUT THE SPONSORS he Michigan Nonprofit Association (MNA) and the Council of Michigan Foundations (CMF) are co-sponsors Tof Michigan in Brief: 2002–03. This handbook and the corresponding Web site are a project of the Michigan Public Policy Initiative (MPPI), an MNA program with which the CMF is affiliated. MICHIGAN NONPROFIT ASSOCIATION The Michigan Nonprofit Association is the collective voice of Michigan’s nonprofit organizations. The association was incorporated in 1990 and has more than 650 members. It provides a statewide network for the nonprofit sector, serves as a management-practices resource for nonprofit organizations, and acts as an advocate for the nonprofit community. The MNA’s mission is to promote the awareness and effectiveness of Michigan’s nonprofit sector. The goals of MNA are the following: n Provide services to the membership. Examples are • information on fundraising, management, taxes, and technology; and • discounts on such items as director and officer liability insurance, long-distance telephone service, classi- fied advertising, and office supplies. -

Annual Agencyclearanceinform

2009 AGENCY CLEARANCE INFORMATION Total Group'A' Group'B' Total Full Time Male Female Civilian Oĸcers Oĸcers Group'A' Group'A' Clearance Group'B' Group'B' Clearance Total Total Clearance Agency Oĸcers Oĸcers Oĸcers Employees Killed Assaulted Incidents Cleared Rate Incidents Cleared Rate Incidents Cleared Rate Adrian Police Department 33 31 2 3 051,620 42926.5% 894 55161.6 % 2,514 980 39.0 % Adrian Township Police Department 22000021 419.0% 9 555.6 % 30 9 30.0 % Albion Police Department 24 21 3 3 00718 425.8% 297 155.1 % 1,015 57 5.6 % Alcona Co. Sheriī's Oĸce 14 14 0 11 00390 8120.8% 134 6347.0 % 524 144 27.5 % Alger Co. Sheriī's Oĸce 11 9 2 2 0012 866.7% 27 2177.8 % 39 29 74.4 % Algonac Police Department 871100132 3526.5% 134 8966.4 % 266 124 46.6 % Allegan Co. Sheriī's Oĸce 61 56 5 47 042,241 93441.7% 2,591 1,87672.4 % 4,832 2,810 58.2 % Allegan Police Department 990100256 9838.3% 228 17476.3 % 484 272 56.2 % Allen Park Police Department 46 44 2 8 001,181 37631.8% 354 27878.5 % 1,535 654 42.6 % Alma Police Department 14 13 1 0 00335 13440.0% 189 12867.7 % 524 262 50.0 % Almont Police Department 761000285 6121.4% 180 11865.6 % 465 179 38.5 % Alpena Co. Sheriī's Oĸce 13 12 1 13 01151 6241.1% 154 11675.3 % 305 178 58.4 % Alpena Police Department 17 17 0 2 00810 11814.6% 560 25645.7 % 1,370 374 27.3 % Ann Arbor Police Department 124 91 33 49 035,065 77015.2% 1,821 1,29271.0 % 6,886 2,062 29.9 % Antrim Co.