Katharine Leiska, Skandinavische

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) – Norwegian and European

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) – Norwegian and European. A critical review By Berit Holth National Library of Norway Edvard Grieg, ca. 1858 Photo: Marcus Selmer Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives The Music Conservatory of Leipzig, Leipzig ca. 1850 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard Grieg graduated from The Music Conservatory of Leipzig, 1862 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard Grieg, 11 year old Alexander Grieg (1806-1875)(father) Gesine Hagerup Grieg (1814-1875)(mother) Cutout of a daguerreotype group. Responsible: Karl Anderson Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard Grieg, ca. 1870 Photo: Hansen & Weller Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives. Original in National Library of Norway Ole Bull (1810-1880) Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832-1910) Wedding photo of Edvard & Nina Grieg (1845-1935), Copenhagen 1867 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard & Nina Grieg with friends in Copenhagen Owner: http://griegmuseum.no/en/about-grieg Capital of Norway from 1814: Kristiania name changed to Oslo Edvard Grieg, ca. 1870 Photo: Hansen & Weller Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives. Original in National Library of Norway From Kvam, Hordaland Photo: Reidun Tveito Owner: National Library of Norway Owner: National Library of Norway Julius Röntgen (1855-1932), Frants Beyer (1851-1918) & Edvard Grieg at Løvstakken, June 1902 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives From Gudvangen, Sogn og Fjordane Photo: Berit Holth Gjendine’s lullaby by Edvard Grieg after Gjendine Slaalien (1871-1972) Owner: National Library of Norway Max Abraham (1831-1900), Oscar Meyer, Nina & Edvard Grieg, Leipzig 1889 Owner: Bergen Public Library. -

Bokvennen Julen 2018 18 90

Bokvennen julen 2018 18 90 Antikvariatet i sentrum - vis à vis Nasjonalgalleriet Bøker - Kart - Trykk - Manuskripter Catilina, Drama i tre Akter af Brynjolf Bjarme Christiania, 1850. Henrik Ibsens debut. kr. 100.000,- Nr. 90 Nr. 89 Nr. 87 Nr. 88 Nr. 91 ViV harharar ogsåoggsså etet godtgodo t utvalguuttvav llg avav IbsensIbIbsseens øvrigeøvrrige dramaer.ddrraammaeerr.. Bokvennen julen 2018 ! Julen 3 Skjønnlitteratur 5 #&),)4)!+&#!#)( 10 Sport og friluftsliv 12 Historie og reiser 14 Krigen 15 Kulturhistorie 16 Kunst og arkitektur 17 Lokalhistorie 18 Mat og drikke 20 Medisin 21 Naturhistorie - og vitenskap 23 Personhistorie 24 Samferdsel og sjøfart 25 !"#$" $$"$! # " Språk 26 %#$""$" " Varia 27 NORLIS ANTIKVARIAT AS Universitetsgaten 18, 0164 Oslo norlis.no 22 20 01 40 [email protected] Åpningstider: Mandag - Fredag 10 - 18 Lørdag: 10 - 16 Søndag: 12 - 16 Bestillingene blir ekspedert i den rekkefølge de innløper. Bøkene kan hentes i forretningen, eller tilsendes. Porto tilkommer. Vennligst oppgi kredittkortdetaljer ved tilsending. Faktura etter avtale (mot fakturagebyr kr. 50,-). Ingen rabatter på katalog-objekter. Våre kart, trykk og manuskripter har merverdiavgift beregnet i henhold til merverdiavgiftsloven § 20 b og er ikke fradragsberettiget som inngående avgift. Vi tar forbehold om trykkfeil. Katalogen legges også ut på nett. Følg med på våre facebook-sider (norlis.no) eller kontakt oss om du vil ha beskjed på e-post. Søndager: Bøker kr. 100,- Trykk og barnebøker kr. 50,- Neste salg på hollandsk vis fra torsdag 10. januar 2018. 1 18 90 Nr.Nr. 173173 - kr.kr. 2.500,-2.500,- Nr.N 1 - kr.k 1.250,- 1 250 Nr.Nr. 89 - kr.kr. 300,-300,- Nr.N 19 - kr.k 425,-425 Nr.NNr 23 - kr.kkr 300,-300 Nr. -

Rehearsal and Concert

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON & MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephones i Ticket Office J g k Ba^ 1492 Branch Exchange \ Administration Offices ) THIRTY- SECOND SEASON, 1912 AND 1913 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Tenth Rehearsal and Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON, DECEMBER 27 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 28 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER 613 — ** After the Symphony Concert ^^ a prolonging of musical pleasure by home-firelight awaits the owner of a "Baldwin." The strongest impressions of the concert season are linked w^ith Baldwintone, exquisitely exploited by pianists eminent in their art. Schnitzer, Pugno, Scharwenka, Bachaus De Pachmann! More than chance attracts the finely-gifted amateur to this keyboard. Among people who love good music, w^ho have a culti- vated knowledge of it, and who seek the best medium for producing it, the Baldwin is chief. In such an atmosphere it is as happily "at home" as are the Preludes of Chopin, the Liszt Rhapsodies upon a virtuoso's programme. THE BOOK OF THE BALDWIN free upon request. CHAS. F. LEONARD, 120 Boylston Street BOSTON, MASS. 614 Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL Thirty-second Season, 1912-1913 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Violins. Witek, A., Roth, 0. Hoffmann, J. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Tak, E. Noack, S. CHICKERING THE STANDARD PIANO SINCE 1823 Piano of American make has been NOso favored by the musical pubHc as this famous old Boston make. The world's greatest musicians have demanded it and discriminating people have purchased it. -

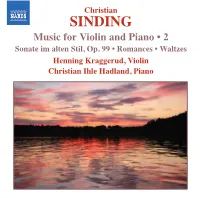

Sinding 2/9/09 10:03 Page 4

572255 bk Sinding 2/9/09 10:03 Page 4 Henning Kraggerud Christian Born in Oslo in 1973, the Norwegian violinist Henning Kraggerud studied with Camilla Wicks and Emanuel Hurwitz and is a recipient of Norway’s prestigious Grieg Prize, the SINDING Ole Bull Prize and the Sibelius Prize. He is a professor at the Barratt Due Institute of Music in Oslo, and appears as a soloist with many of the world’s leading orchestras in Europe, North America, Asia and Australia. He has enjoyed successful artistic collaborations with many conductors including Marek Janowski, Ivan Fischer, Paavo Music for Violin and Piano • 2 Berglund, Kirill Petrenko, Yakov Kreizberg, Mariss Jansons, Stephane Denève and Kurt Sanderling. A committed chamber musician, Henning Kraggerud also performs Sonate im alten Stil, Op. 99 • Romances • Waltzes both on violin and on viola at major international festivals, collaborating with musicians such as Stephen Kovacevich, Kathryn Stott, Leif Ove Andsnes, Jeffrey Kahane, Truls Mørk and Martha Argerich. His recordings include an acclaimed release of the Henning Kraggerud, Violin complete Unaccompanied Violin Sonatas of Ysaÿe for Simax, and he is a winner of the Spellemann CD Award. His recordings for Naxos include Grieg’s Violin Sonatas (8.553904) and Norwegian Favourites (8.554497) for violin and orchestra. He plays a Christian Ihle Hadland, Piano 1744 Guarneri del Gesù instrument (violin bow: Niels Jørgen Røine, Oslo 2003), provided by Dextra Musica AS, a company founded by Sparebankstiftelsen DnB NOR. Christian Ihle Hadland Christian Ihle Hadland was born in Stavanger in 1983. He received his first lessons at the age of eight and at the age of eleven was enrolled at the Rogaland Music Conservatory, later studying with Jiri Hlinka, the teacher of among others Leif Ove Andsnes, at the Barratt Due Institute of Music in Oslo. -

Musikk Og Nasjonalisme Versjon5

HiT skrift nr 3/2008 Musikk og nasjonalisme i Norden Anne Svånaug Haugan, Niels Kayser Nielsen og Peter Stadius (red.) Avdeling for allmennvitenskapelige fag (Bø) Høgskolen i Telemark Porsgrunn 2008 HiT skrift nr 3/2008 ISBN 978- 82-7206-287-2 (trykt) ISBN 978- 82-7206-288-9 (elektronisk) ISSN 1501-8539 (trykt) ISSN 1503-3767 (elektronisk) Serietittel: HiT skrift eller HiT Publication Høgskolen i Telemark Postboks 203 3901 Porsgrunn Telefon 35 57 50 00 Telefaks 35 57 50 01 http://www.hit.no/ Trykk: Kopisenteret. HiT-Bø Forfatterne/Høgskolen i Telemark Det må ikke kopieres fra rapporten i strid med åndsverkloven og fotografiloven, eller i strid med avtaler om kopiering inngått med KOPINOR, interesseorganisasjon for rettighetshavere til åndsverk ii iii Forord Ideen om en konferanse viet temaet musikk og nasjonalisme i Norden ble unnfanget høsten 2005 på et planleggingsmøte i Nordplus-regi på Renvall-institutet i Helsingfors. Denne skulle være en oppfølger av konferansen Språk og nasjonalisme i Norden, i regi av Nordplusnettverket Nordiska erfarenheter arrangert i Helsingfors i august samme år. Ideen var å samles om et hittil lite belyst fellesnordisk prosjekt, som både hadde en historisk og en kulturanalytisk dimmensjon. Ut fra disse kriteriene falt valget på musikk i Norden sett i et historisk og nasjonalt perspektiv, men med den viktige tilføyelse at det ikke skulle fokuseres snevert på den finkulturelle, klassiske musikken. Populærmusikken og folke- og spillemannsmusikken skulle også være representert, primært ut fra en betraktning om at også hverdagslivets "banale" nasjonalisme, som den kommer til uttrykk utenfor kunstmusikken, måtte tas med. Professor Nils Ivar Agøy foreslo at konferansen skulle arrangeres ved Høgskolen i Telemark (HiT), og slik ble det. -

Surgery in Norway a Comprehensive Review at the 100-Year Jubilee of !E Norwegian Surgical Society 1911–2011

Surgery in Norway A Comprehensive Review at the 100-year Jubilee of !e Norwegian Surgical Society 1911–2011 Internet-version - corrected according to suggestions from the members of the Norwegian Surgical Societies, who received a printed “working” version in 2011. Editors: Jon Ha!ner, Tom Gerner and Arnt Jakobsen Copyright 2011: The Norwegian Surgical Association, Oslo Internet version 2012 ISBN nr: 978-82-8070-093-3 Preface The Norwegian Surgical Society was founded on the First The present book is written by leading surgeons in the of August in 1911. The main reason was discontent with different specialties, and all the manuscripts have been the surgeons’ wages and working conditions, but in 1924 reviewed and commented on by other prominent surgeons the focus changed to the scientific aspects of surgery, and to ensure objectivity. membership was opened to surgeons in training. Since then the Society has had annual meetings with free presentations, The initial manuscript was printed and distributed to all mem- and debates about surgical methods, education, specialisa- bers of the surgical societies in Norway (totally 2250) in 2011 tion, leadership, and working conditions. The social aspect for corrections and comments. The present Internet edition has also been important, an annual dinner has been ar- has been corrected according to the comments received, and an ranged since 1925. extra chapter on former Chairmen and Boards of The Norwe- gian Surgical Society/ Assosciation has been added. In 2006 the Society was renamed The Norwegian Surgical Association, with the chairmen of the other surgical socie- The initial manuscript was printed and distributed to all ties as board members. -

National Background: Norway 2015 Bente Granrud (Nasjonalbiblioteket

Date of issue: March 2015 National background: Norway 2015 Bente Granrud (Nasjonalbiblioteket) The most significant repositories of manuscripts and private archives are the National Library of Norway, The National Archives, the regional state archives, The Archives and Library of the Labour Movement, the University Library of Trondheim and the University Library of Bergen. Contents: University of Bergen; Bergen Offentlige Bibliothek; The National Library of Norway, Riksarkivet and Statsarkivene, Oslo; Arbeiderbevegelsens arkiv og bibliotek, Oslo; NTNU Library - Gunnerus Library, Trondheim Universitetsbiblioteken i Bergen http://spesial.b.uib.no/ The Department for Special Collections forms part of the University Library of Bergen, itself a continuation of the old Bergen`s Museum`s Library, founded in 1825. Major holdings: ● The Special Collections incorporates gifts, donations and acquisitions of images, especially photographs, manuscripts, diplomas, maps, antiquarian books and newspapers Bergen Offentlige Bibliotek http://www.bergen.folkebibl.no/grieg-samlingen/grieg_samlingen_intro.html Major holdings: ● Bergen Public Library houses the ‘Edvard Grieg arkiv’: the papers of the composer Edvard Grieg (1843–1907) Nasjonalbibliotheket, Oslo www.nb.no The National Library of Norway was established as an independent institution in 1999. Previously it had been a part of the University Library of Oslo (established 1811), whose collections were divided between the University Library and the National Library in 1999. All holdings of manuscripts (except for papyri) went to the National Library; the University Library of Oslo does not collect that sort of material. Manuscripts and private archives are kept in the department for Research and Dissemination. The main focus is on papers of individuals from ca 1800 onwards, of national interest. -

Jan Dewilde Paper 2009

Frank Van der Stucken (1858-1929): a friend of Grieg and translator of his songs Lecture for International Edvard Grieg Conference, Berlin, 13-16 May 2009 This paper fits in with a research project that is presently being implemented in the library of the Royal Conservatoire of Antwerp about the composer-conductor Frank Van der Stucken. The library preserves a large collection of scores and documents of Van der Stucken, which form the basis of this research. The contacts between Edvard Grieg and the Flemish composer-pianist Arthur De Greef (1862-1940), who met in 1888, are well documented, but the piano virtuoso De Greef wasn’t Grieg’s first Flemish contact. One decade before, Grieg had already got to know an American composer with Flemish roots, namely Frank Van der Stucken. Frank Van der Stucken was born in 1858 in Fredericksburg, Texas, as the son of a Flemish father and a German mother.1 When the Secession War (1861-1865) had finished, the family no longer felt safe in Texas and in 1865 they returned to father Van der Stucken’s native town of Antwerp (Belgium). There Van der Stucken junior studied at the Flemish School of Music – the later Royal Flemish Conservatoire. He was a student of the director Peter Benoit (1834-1901), the standard bearer of nationalist music in Flanders. After his studies with Benoit, Van der Stucken went to Leipzig in 1878, like so many of his contemporaries, with a view to continuing his formation with Carl Reinecke. That’s where he first met Grieg, who became his friend. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 24,1904

ACADEMY OF MUSIC, PHILADELPHIA. BostonSumpIjonyOrcfoestra Mr. WILHELM GERICKE, Conductor. Twentieth Season in Philadelphia. PROGRAMME OF THE Fifth and Last Concert FIRST SERIES, MONDAY EVENING, MARCH 13, AT 8. J 5 PRECISELY. With Historical and Descriptive Notes by Philip Hale* Published by C A. ELLIS, Manager. l js^ai •^Mxrfi « THE MAKERS OF THESE INSTRUMENTS have shown that genius for piano- forte making that has been defined as 'an infinite capacity for taking pains'. The result of over eighty- one years of application of this genius to the production of musical tone is shown in the Chickering of to-day." Catalogue upon Application CHICKERING & SONS Established 182J 7m Tremont St., Boston REPRESENTED IN PHILADELPHIA BY JOHN WANAMAKER : DOStOn ACADEMY OF MUSIC, Symphony § Philadelphia. T Twenty-fourth Season, J904-J905. Of*CnCStt*3. Twentieth Season in Philadelphi a. Mr. WILHELM GERICKE, Conductor. FIFTH AND LAST CONCERT, FIRST SERIES, MONDAY EVENING, MARCH 13, AT 8.15 PRECISELY. PROGRAMME. Sinding " fipisodes Chevaleresques," Suite in F major, for Orchestra, Op. 35. First time at these concerts I. Tempo di marcia. II. Andante funebre. IV. Finale : Allegro moderate Liszt . Concerto No. i, in E-flat major, for Pianoforte and Orchestra Brahms ..... Symphony No. i, in C minor, Op. 68 I. Un poco sostenuto ; Allegro. II. Andante sostenuto. III. Un poco allegretto e grazioso. L' istesso tempo. IV. Adagio ; Allegro non troppo, ma con brio. SOLOIST Mr, ERNEST SCHELLING- The pianoforte Is a Mason & Hamlin. There will be an intermission of ten minutes before the symphony. Opera Singers By QUSTAV KOBB^ A beautiful collection of photographs with biographical sketches of all the grand opera stars, including the newer artists. -

Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos: the Catalogues, Technologies, Archiving and Accessibility

Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos: The Catalogues, Technologies, Archiving and Accessibility Peter Phillips A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Historical Performance Unit Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2016 i Peter Phillips – Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos Declaration I declare that the research presented in this thesis is my own original work and that it contains no material previously published or written by another person. This thesis contains no material that has been submitted to any other institution for the award of a higher degree. All illustrations, graphs, drawings and photographs are by the author, unless otherwise cited. Signed: _______________________ Date: 2___________nd July 2017 Peter Phillips © Peter Phillips 2017 Permanent email address: [email protected] ii Peter Phillips – Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos Acknowledgements A pivotal person in this research project was Professor Neal Peres Da Costa, who encouraged me to undertake a doctorate, and as my main supervisor, provided considerable and insightful guidance while ensuring I presented this thesis in my own way. Professor Anna Reid, my other supervisor, also gave me significant help and support, sometimes just when I absolutely needed it. The guidance from both my supervisors has been invaluable, and I sincerely thank them. One of the greatest pleasures during the course of this research project has been the number of generous people who have provided indispensable help. From a musical point of view, my colleague Glenn Amer spent countless hours helping me record piano rolls, sharing his incredible knowledge and musical skills that often threw new light on a particular work or pianist. -

Grieg Wolf Strauss Grøndahl Lieder & Songs Mari Eriksmoen Alphonse Cemin Menu

GRIEG WOLF STRAUSS GRØNDAHL LIEDER & SONGS MARI ERIKSMOEN ALPHONSE CEMIN MENU › TRACKLIST › TEXTE FRANÇAIS › ENGLISH TEXT › DEUTSCHER TEXT › TEXTES CHANTÉS › SUNG TEXTS › GESUNGENE TEXTE 2 GRIEG WOLF STRAUSS GRØNDAHL LIEDER & SONGS EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907) 1 MENS JEG VENTER 2'34 2 DEN HVIDE, RØDE ROSE 2'17 3 JEG GIVER MITT DIKT TIL VÅREN 1'35 4 EN FUGLEVISE 2'34 5 TO BRUNE ØYNE JEG NYLIG SÅ, OP. 5 1'04 HUGO WOLF (1860-1903) 6 AUCH KLEINE DINGE KÖNNEN UNS ENTZÜCKEN 2'23 7 MIR WARD GESAGT, DU REISEST IN DIE FERNE 2'00 8 DU DENKST MIT EINEM FÄDCHEN MICH ZUFANGEN 1'12 9 NEIN, JUNGER HERR! 0'49 10 ICH HAB IN PENNA EINEN LIEBSTEN WOHNEN 1'01 11 MAUSFALLENSPRÜCHLEIN 1'16 12 DIE SPRÖDE 2'05 13 DIE BEKEHRTE 2'35 14 ER IST’S 1'35 › MENU RICHARD STRAUSS (1864-1949) 15 HERR LENZ 1'23 DREI LIEDER DER OPHELIA OP.67 16 WIE ERKENN ICH MEIN TREULIEB VOR ANDERN NUN? 2'53 17 GUTEN MORGEN, 'S IST SANKT VALENTINSTAG 1'22 18 SIE TRUGEN IHN AUF DER BAHRE BLOß 3'37 19 ICH SCHWEBE WIE AUF ENGELSSCHWINGEN 2'11 AGATHE BACKER-GRØNDAHL (1847-1907) 20 EN KVIDDRENDE LAERKE, OP. 42 NO 1 2'14 21 VAARMORGEN I SKOGEN, OP. 42 NO 2 1'56 22 BLOMSTERSANKING, OP. 42 NO 4 0'57 23 MOT KVELD, OP. 42 NO 7 2'14 24 SOV SAA STILLE, OP. 42 NO 8 3'12 TOTAL TIME: 47'12 MARI ERIKSMOEN SOPRANO ALPHONSE CEMIN PIANO › MENU À L’HORIZON DU ROMANTISME Du temps d’Edvard Grieg (1843-1907), la Norvège est une nation nouvelle, certes encore sous la dépendance du roi de Suède, pays auquel elle est rattachée. -

Musikbladet (1884-1895) Copyright © 1997 RIPM Consortium Ltd Répertoire International De La Presse Musicale ( Musikbladet (1884-1895)

Introduction to: Kirsti Grinde, Musikbladet (1884-1895) Copyright © 1997 RIPM Consortium Ltd Répertoire international de la presse musicale (www.ripm.org) Musikbladet (1884-1895) Musikbladet [The music magazine] [MBL]—subtitled Ugerevue for Musik og Theater [Weekly review for music and theater]—was published in Copenhagen from October 1884 to March 1895 by the music publisher Wilhelm Hansen.1 Financial support came from advertisers and subscribers with, one can assume, support from its wealthy publisher when necessary. From its inception through 2 May 1885 Musikbladet appeared weekly and contained eight pages. A double issue of twenty-one pages was published on 14 May 1885, and weekly single issues of eight pages appeared on 23 and 30 May 1885. On 13 June a double issue of twelve pages appeared, with two single issues (eight pages each) following on 20 and 27 June. Only one issue appeared in July 1885. Thereafter the journal was published twice monthly for the remainder of the year. Clearly, weekly publication was too ambitious a goal as was the publication of eight-page issues.2 Between 1 January 1886 and [December] 1892 the journal published (albeit irregularly) twenty-four numbers each year consisting of both single and double issues. In 1893 five double and two single issues were published.3 Thereafter, publication concluded with two double issues (of twelve and sixteen pages respectively), one dated October 1894, the other March 1895. With the exception of its last two issues the journal’s size was, with some variation, 21.7cm x 30.6cm.4 Throughout, its text is printed in a two-column format, and its pages are numbered consecutively from the outset of each new year.