The Complete Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) – Norwegian and European

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) – Norwegian and European. A critical review By Berit Holth National Library of Norway Edvard Grieg, ca. 1858 Photo: Marcus Selmer Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives The Music Conservatory of Leipzig, Leipzig ca. 1850 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard Grieg graduated from The Music Conservatory of Leipzig, 1862 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard Grieg, 11 year old Alexander Grieg (1806-1875)(father) Gesine Hagerup Grieg (1814-1875)(mother) Cutout of a daguerreotype group. Responsible: Karl Anderson Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard Grieg, ca. 1870 Photo: Hansen & Weller Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives. Original in National Library of Norway Ole Bull (1810-1880) Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832-1910) Wedding photo of Edvard & Nina Grieg (1845-1935), Copenhagen 1867 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard & Nina Grieg with friends in Copenhagen Owner: http://griegmuseum.no/en/about-grieg Capital of Norway from 1814: Kristiania name changed to Oslo Edvard Grieg, ca. 1870 Photo: Hansen & Weller Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives. Original in National Library of Norway From Kvam, Hordaland Photo: Reidun Tveito Owner: National Library of Norway Owner: National Library of Norway Julius Röntgen (1855-1932), Frants Beyer (1851-1918) & Edvard Grieg at Løvstakken, June 1902 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives From Gudvangen, Sogn og Fjordane Photo: Berit Holth Gjendine’s lullaby by Edvard Grieg after Gjendine Slaalien (1871-1972) Owner: National Library of Norway Max Abraham (1831-1900), Oscar Meyer, Nina & Edvard Grieg, Leipzig 1889 Owner: Bergen Public Library. -

Bokvennen Julen 2018 18 90

Bokvennen julen 2018 18 90 Antikvariatet i sentrum - vis à vis Nasjonalgalleriet Bøker - Kart - Trykk - Manuskripter Catilina, Drama i tre Akter af Brynjolf Bjarme Christiania, 1850. Henrik Ibsens debut. kr. 100.000,- Nr. 90 Nr. 89 Nr. 87 Nr. 88 Nr. 91 ViV harharar ogsåoggsså etet godtgodo t utvalguuttvav llg avav IbsensIbIbsseens øvrigeøvrrige dramaer.ddrraammaeerr.. Bokvennen julen 2018 ! Julen 3 Skjønnlitteratur 5 #&),)4)!+&#!#)( 10 Sport og friluftsliv 12 Historie og reiser 14 Krigen 15 Kulturhistorie 16 Kunst og arkitektur 17 Lokalhistorie 18 Mat og drikke 20 Medisin 21 Naturhistorie - og vitenskap 23 Personhistorie 24 Samferdsel og sjøfart 25 !"#$" $$"$! # " Språk 26 %#$""$" " Varia 27 NORLIS ANTIKVARIAT AS Universitetsgaten 18, 0164 Oslo norlis.no 22 20 01 40 [email protected] Åpningstider: Mandag - Fredag 10 - 18 Lørdag: 10 - 16 Søndag: 12 - 16 Bestillingene blir ekspedert i den rekkefølge de innløper. Bøkene kan hentes i forretningen, eller tilsendes. Porto tilkommer. Vennligst oppgi kredittkortdetaljer ved tilsending. Faktura etter avtale (mot fakturagebyr kr. 50,-). Ingen rabatter på katalog-objekter. Våre kart, trykk og manuskripter har merverdiavgift beregnet i henhold til merverdiavgiftsloven § 20 b og er ikke fradragsberettiget som inngående avgift. Vi tar forbehold om trykkfeil. Katalogen legges også ut på nett. Følg med på våre facebook-sider (norlis.no) eller kontakt oss om du vil ha beskjed på e-post. Søndager: Bøker kr. 100,- Trykk og barnebøker kr. 50,- Neste salg på hollandsk vis fra torsdag 10. januar 2018. 1 18 90 Nr.Nr. 173173 - kr.kr. 2.500,-2.500,- Nr.N 1 - kr.k 1.250,- 1 250 Nr.Nr. 89 - kr.kr. 300,-300,- Nr.N 19 - kr.k 425,-425 Nr.NNr 23 - kr.kkr 300,-300 Nr. -

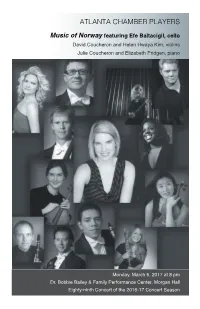

Atlanta Chamber Players, "Music of Norway"

ATLANTA CHAMBER PLAYERS Music of Norway featuring Efe Baltacigil, cello David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins Julie Coucheron and Elizabeth Pridgen, piano Monday, March 6, 2017 at 8 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Eighty-ninth Concert of the 2016-17 Concert Season program JOHAN HALVORSEN (1864-1935) Concert Caprice on Norwegian Melodies David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907) Andante con moto in C minor for Piano Trio David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello Julie Coucheron, piano EDVARD GRIEG Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 45 Allegro molto ed appassionato Allegretto espressivo alla Romanza Allegro animato - Prestissimo David Coucheron, violin Julie Coucheron, piano INTERMISSION JOHAN HALVORSEN Passacaglia for Violin and Cello (after Handel) David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello EDVARD GRIEG Cello Sonata in A minor, Op. 36 Allegro agitato Andante molto tranquillo Allegro Efe Baltacigil, cello Elizabeth Pridgen, piano featured musician FE BALTACIGIL, Principal Cello of the Seattle Symphony since 2011, was previously Associate Principal Cello of The Philadelphia Orchestra. EThis season highlights include Brahms' Double Concerto with the Oslo Radio Symphony and Vivaldi's Double Concerto with the Seattle Symphony. Recent highlights include his Berlin Philharmonic debut under Sir Simon Rattle, performing Bottesini’s Duo Concertante with his brother Fora; performances of Tchaikovsky’s Variations on a Rococo Theme with the Bilkent & Seattle Symphonies; and Brahms’ Double Concerto with violinist Juliette Kang and the Curtis Symphony Orchestra. Baltacıgil performed a Brahms' Sextet with Itzhak Perlman, Midori, Yo-Yo Ma, Pinchas Zukerman and Jessica Thompson at Carnegie Hall, and has participated in Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Project. -

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER the CANOPY of MY LIFE Artistic, Creative, Musical Pedagogy, Public and Private

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER THE CANOPY OF MY LIFE Artistic, creative, musical pedagogy, public and private Translated by John Ranck But1 you are getting old, pick Flowers, growing on the graves And with them renew your heart. Nekrasov2 And ethereally brightening-within-me Beloved shadows arose in the Argentine mist Balmont3 The Tcherepnins are from the vicinity of Izborsk, an ancient Russian town in the Pskov province. If I remember correctly, my aged aunts lived on an estate there which had been passed down to them by their fathers and grandfathers. Our lineage is not of the old aristocracy, and judging by excerpts from the book of Records of the Nobility of the Pskov province, the first mention of the family appears only in the early 19th century. I was born on May 3, 1873 in St. Petersburg. My father, a doctor, was lively and very gifted. His large practice drew from all social strata and included literary luminaries with whom he collaborated as medical consultant for the gazette, “The Voice” that was published by Kraevsky.4 Some of the leading writers and poets of the day were among its editors. It was my father’s sorrowful duty to serve as Dostoevsky’s doctor during the writer’s last illness. Social activities also played a large role in my father’s life. He was an active participant in various medical societies and frequently served as chairman. He also counted among his patients several leading musical and theatrical figures. My father was introduced to the “Mussorgsky cult” at the hospitable “Tuesdays” that were hosted by his colleague, Dr. -

Conference Program 2011

Grieg Conference in Copenhagen 11 to 13 August 2011 CONFERENCE PROGRAM 16.15: End of session Thursday 11 August: 17.00: Reception at Café Hammerich, Schæffergården, invited by the 10.30: Registration for the conference at Schæffergården Norwegian Ambassador 11.00: Opening of conference 19.30: Dinner at Schæffergården Opening speech: John Bergsagel, Copenhagen, Denmark Theme: “... an indefinable longing drove me towards Copenhagen" 21.00: “News about Grieg” . Moderator: Erling Dahl jr. , Bergen, Norway Per Dahl, Arvid Vollsnes, Siren Steen, Beryl Foster, Harald Herresthal, Erling 12.00: Lunch Dahl jr. 13.00: Afternoon session. Moderator: Øyvind Norheim, Oslo, Norway Friday 12 August: 13.00: Maria Eckhardt, Budapest, Hungary 08.00: Breakfast “Liszt and Grieg” 09.00: Morning session. Moderator: Beryl Foster, St.Albans, England 13.30: Jurjen Vis, Holland 09.00: Marianne Vahl, Oslo, Norway “Fuglsang as musical crossroad: paradise and paradise lost” - “’Solveig`s Song’ in light of Søren Kierkegaard” 14.00: Gregory Martin, Illinois, USA 09.30: Elisabeth Heil, Berlin, Germany “Lost Among Mountain and Fjord: Mythic Time in Edvard Grieg's Op. 44 “’Agnete’s Lullaby’ (N. W. Gade) and ‘Solveig’s Lullaby’ (E. Grieg) Song-cycle” – Two lullabies of the 19th century in comparison” 14.30: Coffee/tea 10.00: Camilla Hambro, Åbo, Finland “Edvard Grieg and a Mother’s Grief. Portrait with a lady in no man's land” 14.45: Constanze Leibinger, Hamburg, Germany “Edvard Grieg in Copenhagen – The influence of Niels W. Gade and 10.30: Coffee/tea J.P.E. Hartmann on his specific Norwegian folk tune.” 10.40: Jorma Lünenbürger, Berlin, Germany / Helsinki, Finland 15.15: Rune Andersen, Bjästa, Sweden "Grieg, Sibelius and the German Lied". -

Johan HALVORS Saraband Passacagl Concert C

8.572522 bk Halvorsen_Bruni_EU:8.572522 bk Halvorsen_Bruni_EU 16-08-2011 9:02 Pagina 1 Natalia Lomeiko Natalia Lomeiko launched her solo career at the age of seven with the Novosibirsk Philharmonic. A few years later she was invited to study at the Yehudi Menuhin School, hailed by Menuhin as ‘one of the most brilliant of our younger violinists’. After completing her studies at the Royal College and the Photo: Sasha Gusov Photo: Royal Academy of Music she won several prestigious international competi- Johan tions, including first prize in the Premio Paganini in Italy and Michael Hill in New Zealand. She has appeared with major orchestras around the world, including the St Petersburg Radio Symphony, Tokyo Royal Philharmonic, the New HALVORSEN Zealand Symphony, Auckland Philharmonia, Melbourne Symphony, Royal Philharmonic and many other orchestras. She has performed chamber music Also available with such renowned musicians as Gidon Kremer, Tabea Zimmermann, Dmitry Sarabande Sitkovetsky, Shlomo Mintz, Boris Pergamenschikov, Isabelle Faust and Yuri Bashmet. She has recorded for Dynamic, Foné and Trust Records with pianist Olga Sitkovetsky. In 2010 she was appointed Professor of Violin at the Royal College of Music in London. Passacaglia http://www.natalialomeiko.com http://www.lomeikozhislinduo.com Concert Caprice on Yuri Zhislin Norwegian Melodies Yuri Zhislin became the BBC Radio Two Young Musician of the Year in 1993 and has performed throughout Europe, America, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. He regularly appears both on the violin and the viola at festivals around the world. His chamber music partners have included María João Pires, Dmitry Sitkovetsky and Natalie Clein. -

Rehearsal and Concert

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON & MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephones i Ticket Office J g k Ba^ 1492 Branch Exchange \ Administration Offices ) THIRTY- SECOND SEASON, 1912 AND 1913 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Tenth Rehearsal and Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON, DECEMBER 27 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 28 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER 613 — ** After the Symphony Concert ^^ a prolonging of musical pleasure by home-firelight awaits the owner of a "Baldwin." The strongest impressions of the concert season are linked w^ith Baldwintone, exquisitely exploited by pianists eminent in their art. Schnitzer, Pugno, Scharwenka, Bachaus De Pachmann! More than chance attracts the finely-gifted amateur to this keyboard. Among people who love good music, w^ho have a culti- vated knowledge of it, and who seek the best medium for producing it, the Baldwin is chief. In such an atmosphere it is as happily "at home" as are the Preludes of Chopin, the Liszt Rhapsodies upon a virtuoso's programme. THE BOOK OF THE BALDWIN free upon request. CHAS. F. LEONARD, 120 Boylston Street BOSTON, MASS. 614 Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL Thirty-second Season, 1912-1913 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Violins. Witek, A., Roth, 0. Hoffmann, J. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Tak, E. Noack, S. CHICKERING THE STANDARD PIANO SINCE 1823 Piano of American make has been NOso favored by the musical pubHc as this famous old Boston make. The world's greatest musicians have demanded it and discriminating people have purchased it. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 65,1945-1946

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 1492 SIXTY-FIFTH SEASON, 1945-1946 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, I945, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, ItlC. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot . President Henry B. Sawyer . Vice-President Richard C. Paine . Treasurer Philip R. Allen M. A. Be Wolfe Howe John Nicholas Brown Jacob J. Kaplan Alvan T. Fuller Roger I. Lee Jerome D. Greene Bentley W. Warren N. Penrose Hallowell Oliver Wolcott G. E. Judd, Manager [453 1 ®**65 © © © © © © © © © © © © © © © © © © © Time for Revi ew ? © © Are your plans for the ultimate distribu- © © tion of your property up-to-date? Changes © in your family situation caused by deaths, © births, or marriages, changes in the value © © of your assets, the need to meet future taxes © . these are but a few of the factors that © suggest a review of your will. © We invite you and your attorney to make © use of our experience in property manage- © ment and settlement of estates by discuss- © program with our Trust Officers. © ing your © © PERSONAL TRUST DEPARTMENT © © The V^Cational © © © Shawmut Bank © Street^ Boston © 40 Water © Member Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation © Capital % 10,000,000 Surplus $20,000,000 © "Outstanding Strength" for 108 Years © © © ^oHc^;c^oH(§@^a^^^aa^aa^^@^a^^^^^©©©§^i^ SYMPHONIANA Musical Exposure Exhibition MUSICAL EXPOSURE Among the chamber concerts organ- ized by members of this orchestra, there is special interest in the venture of the Zimbler String Quartet. Augmented by a flute, clarinet, or harpsichord, they are acquainting the pupils of high schools with this kind of music. -

3Johan Halvorsen

Johan Halvorsen 3 ORCHESTRAL WORKS Ragnhild Hemsing Hardanger fiddle Marianne Thorsen violin Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra Neeme Järvi Aftenposten / Press Association Images Johan Halvorsen, at home in Oslo, on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, 15 March 1934; the wintry scene depicted on the wall behind him is one of his own paintings Johan Halvorsen (1864 –1935) Orchestral Works, Volume 3 Symphony No. 3 26:12 in C major • in C-Dur • en ut majeur Edited by Jørn Fossheim 1 I Poco andante – Allegro moderato – Tranquillo – Poco più mosso – A tempo. Molto più mosso – Tranquillo – Un poco più mosso – Molto energico – Meno mosso – [A tempo] – Più allegro 9:23 2 II Andante – Allegro moderato – Tranquillo – Allegro molto – Andante. Tempo I – Adagio 7:58 3 III Finale. Allegro impetuoso – Poco meno mosso – Tranquillo – Stretto – Animando – Poco a poco meno mosso – Un poco tranquillo – Largamente – A tempo, più mosso – Tempo I – Poco meno mosso – Tranquillo – Poco meno mosso – Largamente – Andante – Allegro (Tempo I) – Stesso tempo – Più allegro 8:46 premiere recording 4 Sorte Svaner 4:54 (Black Swans) Andante – Più mosso – Un poco animato 3 5 Bryllupsmarsch, Op. 32 No. 1* 4:13 (Wedding March) for Violin Solo and Orchestra Til Arve Arvesen Allegretto marziale – Coda premiere recording 6 Rabnabryllaup uti Kraakjalund 3:59 (Wedding of Ravens in the Grove of the Crows) Norwegian Folk Melody Arranged for String Orchestra Andante Fossegrimen, Op. 21† 29:49 Dramatic Suite for Orchestra Deres Majestæter Kong Håkon VII. og Dronning Maud i dybeste ærbødighed tilegnet Melina Mandozzi violin 7 I Fossegrimen. Allegro moderato – Meno allegro – Più lento – Più vivo – Più allegro – Un poco più allegro – Tempo I, ma un poco meno mosso – Allegro molto 6:29 8 II Huldremøyarnes Dans. -

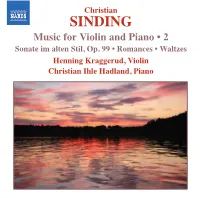

Sinding 2/9/09 10:03 Page 4

572255 bk Sinding 2/9/09 10:03 Page 4 Henning Kraggerud Christian Born in Oslo in 1973, the Norwegian violinist Henning Kraggerud studied with Camilla Wicks and Emanuel Hurwitz and is a recipient of Norway’s prestigious Grieg Prize, the SINDING Ole Bull Prize and the Sibelius Prize. He is a professor at the Barratt Due Institute of Music in Oslo, and appears as a soloist with many of the world’s leading orchestras in Europe, North America, Asia and Australia. He has enjoyed successful artistic collaborations with many conductors including Marek Janowski, Ivan Fischer, Paavo Music for Violin and Piano • 2 Berglund, Kirill Petrenko, Yakov Kreizberg, Mariss Jansons, Stephane Denève and Kurt Sanderling. A committed chamber musician, Henning Kraggerud also performs Sonate im alten Stil, Op. 99 • Romances • Waltzes both on violin and on viola at major international festivals, collaborating with musicians such as Stephen Kovacevich, Kathryn Stott, Leif Ove Andsnes, Jeffrey Kahane, Truls Mørk and Martha Argerich. His recordings include an acclaimed release of the Henning Kraggerud, Violin complete Unaccompanied Violin Sonatas of Ysaÿe for Simax, and he is a winner of the Spellemann CD Award. His recordings for Naxos include Grieg’s Violin Sonatas (8.553904) and Norwegian Favourites (8.554497) for violin and orchestra. He plays a Christian Ihle Hadland, Piano 1744 Guarneri del Gesù instrument (violin bow: Niels Jørgen Røine, Oslo 2003), provided by Dextra Musica AS, a company founded by Sparebankstiftelsen DnB NOR. Christian Ihle Hadland Christian Ihle Hadland was born in Stavanger in 1983. He received his first lessons at the age of eight and at the age of eleven was enrolled at the Rogaland Music Conservatory, later studying with Jiri Hlinka, the teacher of among others Leif Ove Andsnes, at the Barratt Due Institute of Music in Oslo. -

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto Friday, January 12, 2018 at 11 am Jayce Ogren, Guest conductor Sibelius Symphony No. 7 in C Major Tchaikovsky Concerto for Violin and Orchestra Gabriel Lefkowitz, violin Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto For Tchaikovsky and The Composers Sibelius, these works were departures from their previ- ous compositions. Both Jean Sibelius were composed in later pe- (1865—1957) riods in these composers’ lives and both were pushing Johan Christian Julius (Jean) Sibelius their comfort levels. was born on December 8, 1865 in Hämeenlinna, Finland. His father (a doctor) died when Jean For Tchaikovsky, the was three. After his father’s death, the family Violin Concerto came on had to live with a variety of relatives and it was Jean’s aunt who taught him to read music and the heels of his “year of play the piano. In his teen years, Jean learned the hell” that included his disas- violin and was a quick study. He formed a trio trous marriage. It was also with his sister older Linda (piano) and his younger brother Christian (cello) and also start- the only concerto he would ed composing, primarily for family. When Jean write for the violin. was ready to attend university, most of his fami- Jean Sibelius ly (Christian stayed behind) moved to Helsinki For Sibelius, his final where Jean enrolled in law symphony became a chal- school but also took classes at the Helsinksi Music In- stitute. Sibelius quickly became known as a skilled vio- lenge to synthesize the tra- linist as well as composer. He then spent the next few ditional symphonic form years in Berlin and Vienna gaining more experience as a composer and upon his return to Helsinki in 1892, he with a tone poem. -

Musikk Og Nasjonalisme Versjon5

HiT skrift nr 3/2008 Musikk og nasjonalisme i Norden Anne Svånaug Haugan, Niels Kayser Nielsen og Peter Stadius (red.) Avdeling for allmennvitenskapelige fag (Bø) Høgskolen i Telemark Porsgrunn 2008 HiT skrift nr 3/2008 ISBN 978- 82-7206-287-2 (trykt) ISBN 978- 82-7206-288-9 (elektronisk) ISSN 1501-8539 (trykt) ISSN 1503-3767 (elektronisk) Serietittel: HiT skrift eller HiT Publication Høgskolen i Telemark Postboks 203 3901 Porsgrunn Telefon 35 57 50 00 Telefaks 35 57 50 01 http://www.hit.no/ Trykk: Kopisenteret. HiT-Bø Forfatterne/Høgskolen i Telemark Det må ikke kopieres fra rapporten i strid med åndsverkloven og fotografiloven, eller i strid med avtaler om kopiering inngått med KOPINOR, interesseorganisasjon for rettighetshavere til åndsverk ii iii Forord Ideen om en konferanse viet temaet musikk og nasjonalisme i Norden ble unnfanget høsten 2005 på et planleggingsmøte i Nordplus-regi på Renvall-institutet i Helsingfors. Denne skulle være en oppfølger av konferansen Språk og nasjonalisme i Norden, i regi av Nordplusnettverket Nordiska erfarenheter arrangert i Helsingfors i august samme år. Ideen var å samles om et hittil lite belyst fellesnordisk prosjekt, som både hadde en historisk og en kulturanalytisk dimmensjon. Ut fra disse kriteriene falt valget på musikk i Norden sett i et historisk og nasjonalt perspektiv, men med den viktige tilføyelse at det ikke skulle fokuseres snevert på den finkulturelle, klassiske musikken. Populærmusikken og folke- og spillemannsmusikken skulle også være representert, primært ut fra en betraktning om at også hverdagslivets "banale" nasjonalisme, som den kommer til uttrykk utenfor kunstmusikken, måtte tas med. Professor Nils Ivar Agøy foreslo at konferansen skulle arrangeres ved Høgskolen i Telemark (HiT), og slik ble det.