Twentieth-Century Problems of Female Inheritance in Kano Emirate, Nigeria*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

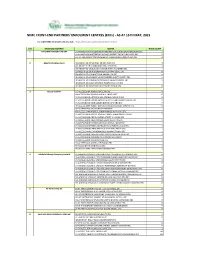

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Under Exclusive License to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021 A

INDEX1 A African Renaissance, 11, 39 Abada, 124 Afrocentricity, 13, 77–89 Academic Staff Union of Universities Afrocentrism, 9, 11, 79, 82 (ASUU), 70 Afropolitan, 134, 135, 172 Adire eleko, 124, 126, 128, 129, 131 Agency, 6, 13, 63, 68, 77–89, 95–97, Africa, 3–6, 8, 9, 11–15, 21, 22n4, 101, 106, 107, 116n7, 154, 187, 35–42, 46, 47, 49, 51, 53–56, 196, 198, 206 61–73, 78–83, 86–89, 111–121, Agogo, 210, 211, 215, 216 123–138, 142–153, 155–159, Akan, 29n18, 115, 117, 117n8, 154 165–171, 173, 174, 178, 190, Ake, Claude, 61, 119 198, 200, 221–223 Akwete, 136 African architecture, 14, 141–160 Ala, 186 African epistemology, 13, 15, 19–32, al-Jami’ al-Saghir, 225 36, 44, 56, 81, 82 al-Shifa, 225 African ethics, 53, 54 Amadiume, If, 170, 171, 173, African indigenous knowledge system 178, 187 (AIKS), 9, 10, 12–14, 36–40, Animism, 14, 94, 96–98, 100 42–46, 49, 51, 54–56, 85–88 Ankara, 124 Africanity, 8, 9, 11, 12, 127, 128, Anthropocentrism, 14, 93–95, 133–135, 137 104, 109 Africanization, 37, 39, 40, 55 Anthropomorphism, 102 African print, 14, 123–138 Anticolonialism, 5, 7 1 Note: Page numbers followed by ‘n’ refer to notes. © The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature 235 Switzerland AG 2021 A. Afolayan et al. (eds.), Pathways to Alternative Epistemologies in Africa, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60652-7 236 INDEX Architecture, 14, 81, 141–160 Communitarianism, 116, 118–120 Asante, Molef Kete, 40–42, 43n3, 45, Community, 10, 11, 13, 14, 20, 79–82, 84, 125, 136 26–28, 29n18, 31, 36, 39, 42, Ashcroft, Bill, 1, 7 44–46, 48–54, -

Ebook Download This Is Grime Ebook, Epub

THIS IS GRIME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hattie Collins | 320 pages | 04 Apr 2017 | HODDER & STOUGHTON | 9781473639270 | English | London, United Kingdom This Is Grime PDF Book The grime scene has been rapidly expanding over the last couple of years having emerged in the early s in London, with current grime artists racking up millions of views for their quick-witted and contentious tracks online and filling out shows across the country. Sign up to our weekly e- newsletter Email address Sign up. The "Daily" is a reference to the fact that the outlet originally intended to release grime related content every single day. Norway adjusts Covid vaccine advice for doctors after admitting they 'cannot rule out' side effects from the Most Popular. The awkward case of 'his or her'. Definition of grime. This site uses cookies. It's all fun and games until someone beats your h Views Read Edit View history. During the hearing, David Purnell, defending, described Mondo as a talented musician and sportsman who had been capped 10 times representing his country in six-a-side football. Fernie, aka Golden Mirror Fortunes, is a gay Latinx Catholic brujx witch — a combo that is sure to resonate…. Scalise calls for House to hail Capitol Police officers. Drill music, with its slower trap beats, is having a moment. Accessed 16 Jan. This Is Grime. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. More On: penn station. Police are scrambling to recover , pieces of information which were WIPED from records in blunder An unwillingness to be chained to mass-produced labels and an unwavering honesty mean that grime is starting a new movement of backlash to the oppressive systems of contemporary society through home-made beats and backing tracks and enraged lyrics. -

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: the Role of Traditional Institutions

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Edited by Abdalla Uba Adamu ii Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Proceedings of the National Conference on Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria. Organized by the Kano State Emirate Council to commemorate the 40th anniversary of His Royal Highness, the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD, as the Emir of Kano (October 1963-October 2003) H.R.H. Alhaji (Dr.) Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD 40th Anniversary (1383-1424 A.H., 1963-2003) Allah Ya Kara Jan Zamanin Sarki, Amin. iii Copyright Pages © ISBN © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors. iv Contents A Brief Biography of the Emir of Kano..............................................................vi Editorial Note........................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................i Opening Lead Papers Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: The Role of Traditional Institutions...........1 Lt. General Aliyu Mohammed (rtd), GCON Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Sarkin Kano Alhaji Ado Bayero and the Kano Emirate Council...............................................................14 Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, M.A. (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) -

SK Abdullahi Bayero

Sarkin Kano Abdullahi Bayero (1926-1953) bdullahi Bayero was born in 1299 AH (1881). He had his early Islamic education Aat the Sarki's palace and he was guided by the prominent Islamic scholars of the time. While he was the Ciroma of Kano and District Head of Bichi he became very closely associated with the prominent Ulama of his time. When the British colonial administrators decided to introduce the new district administrative structure, Abdullahi Bayero, who was then Ciroma, was appointed the Head of the Home Districts with Headquarters at Dawakin Kudu and later Panisau in 1914. He was appointed Sarkin Kano in April 1926 and was formally installed on 14th February 1927 (Fika 1978: 227). He was the most experienced contender for the Emirship he had also proved that he was honest, efficient, dedicated and upright. Abdullahi Bayero made several appointments during his long and highly respected reign. Among those he appointed were his sons Muhammad Sanusi whom he appointed Ciroma and District Head of Bichi the position he held before his appointment as the Sarki, and Aminu who was appointed Dan Iya and District Head of Dawakin Kudu. After the deposition of Muhammad son of Sarkin Kano Shehu Usman from Turaki and District Head of Ungogo he appointed his brothers Abdulkadir and Muhammad Inuwa as Galadima and Turaki respectively in 1927. Gidan Agogo He reduced, the influence of the Cucanawa and also ©Ibrahim Ado-Kurawa 2019 Sullubawan Dabo: An Illustrated History 1819-2019 freed all other royal slaves, which was in line with Ibrahim Niass of Senegal and they accepted him the British anti-slavery policy. -

A Reinterpretation of Islamic Foundation of Jihadist Movements in West Africa

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1 | Jan-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.001 Research Article A Reinterpretation of Islamic Foundation of Jihadist Movements in West Africa Dr. Usman Abubakar Daniya*1 & Dr. Umar Muhammad Jabbi2 1,2Department of History, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, Nigeria Abstract: It is no exaggeration that the Jihads of the 19th century West Africa were Article History phenomenal and their study varied. Plenty have been written about their origin, development Received: 04.12.2019 and the decline of the states they established. But few scholars have delved into the actual Accepted: 11.12.2019 settings that surrounded their emergence. And while many see them as a result of the Published: 15.01.2020 beginning of Islamic revivalism few opined that they are the continuation of it. This paper Journal homepage: first highlights the state of Islam in the region; the role of both the scholars, students and th https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs rulers from the 14 century, in its development and subsequently its spread among the people of the region as impetus to the massive awareness and propagation of the faith that Quick Response Code was to led to the actions and reactions that subsequently led to the revolutions. The paper, contrary to many assertions, believes that it was actually the growth of Islamic learning and scholarship and not its decline that led to the emergence and successes of the Jihad movements in the upper and Middle Niger region area. -

The Kano Durbar: Political Aesthetics in the Bowel of the Elephant

Original Article The Kano Durbar: Political aesthetics in the bowel of the elephant Wendy Griswolda,* and Muhammed Bhadmusb aDepartment of Sociology, Northwestern University, 1810 Chicago Avenue, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA. E-mail: [email protected] bDepartment of Theatre and Drama, Bayero University Kano, Kano, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author. Abstract Political aesthetics deploy theatrical techniques to unite performers and audience into a cultural community, thereby distracting from conflicts. The Kano Durbar in northern Nigeria demonstrates how the aesthetics of power can promote a place-based political culture. Although power in Kano rests on a wobbly three-legged stool of traditional, constitutional and religious authority, the status quo celebrated by the Durbar holds back ideological challengers like Boko Haram even as it perpetuates distance from the unified nation-state. The Durbar works as a social drama that helps sustain a Kano-based collective solidarity against the threats of ethnic/religious tensions and Salafist extremism. A cultural-sociological and dramaturgical analysis of the Durbar demonstrates how weak sources of power can support one another when bound together in an aesthetically compelling ritual. American Journal of Cultural Sociology (2013) 1, 125–151. doi:10.1057/ajcs.2012.8 Keywords: political aesthetics; place; social drama; Kano; Nigeria; Durbar Introduction While political rituals are expressions of power, what is less often noticed is that they are expressions of place. Bringing this insight to bear on the analysis of these rituals can reveal how they work, what exactly they accomplish, thereby resolving some of the puzzles they present. This article examines the case of the Kano Durbar, a Nigerian ritual that presents a social drama of and for Kano residents, a drama that helps sustain a sense of r 2013 Macmillan Publishers Ltd. -

Rainfall and the Length of the Growing Season in Nigeria

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CLIMATOLOGY Int. J. Climatol. 24: 467–479 (2004) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/joc.1012 RAINFALL AND THE LENGTH OF THE GROWING SEASON IN NIGERIA T. O. ODEKUNLE* Department of Geography, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria Received 15 May 2003 Revised 8 December 2003 Accepted 16 December 2003 ABSTRACT This study examines the length of the growing season in Nigeria using the daily rainfall data of Ikeja, Ondo, Ilorin, Kaduna and Kano. The data were collected from the archives of the Nigerian Meteorological Services, Oshodi, Lagos. The length of the growing season was determined using the cumulative percentage mean rainfall and daily rainfall probability methods. Although rainfall in Ikeja, Ondo, Ilorin, Kaduna, and Kano appears to commence around the end of the second dekad of March, middle of the third dekad of March, mid April, end of the first dekad of May, and early June respectively, its distribution characteristics at the respective stations remain inadequate for crop germination, establishment, and development till the end of the second dekad of May, early third dekad of May, mid third dekad of May, end of May, and end of the first dekad of July respectively. Also, rainfall at the various stations appears to retreat starting from the early third dekad of October, early third dekad of October, end of the first dekad of October, end of September, and early second dekad of September respectively, but its distribution characteristics only remain adequate for crop development at the respective stations till around the end of the second dekad of October, end of the second dekad of October, middle of the first dekad of October, early October, and middle of the first dekad of September respectively. -

Religions and Development Research Programme

Religions and Development Research Programme Comparing Religious and Secular NGOs in Nigeria: are Faith-Based Organizations Distinctive? Comfort Davis Independent researcher Ayodele Jegede University of Ibadan Robert Leurs International Development Department, University of Birmingham Adegbenga Sunmola University of Ibadan Ukoha Ukiwo Department of Political and Administrative Studies, University of Port Harcourt Working Paper 56 - 2011 Religions and Development Research Programme The Religions and Development Research Programme Consortium is an international research partnership that is exploring the relationships between several major world religions, development in low-income countries and poverty reduction. The programme is comprised of a series of comparative research projects that are addressing the following questions: How do religious values and beliefs drive the actions and interactions of individuals and faith-based organisations? How do religious values and beliefs and religious organisations influence the relationships between states and societies? In what ways do faith communities interact with development actors and what are the outcomes with respect to the achievement of development goals? The research aims to provide knowledge and tools to enable dialogue between development partners and contribute to the achievement of development goals. We believe that our role as researchers is not to make judgements about the truth or desirability of particular values or beliefs, nor is it to urge a greater or lesser role for religion in achieving development objectives. Instead, our aim is to produce systematic and reliable knowledge and better understanding of the social world. The research focuses on four countries (India, Pakistan, Nigeria and Tanzania), enabling the research team to study most of the major world religions: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism and African traditional belief systems. -

Nigeria Update to the IMB Nigeria

Progress in Polio Eradication Initiative in Nigeria: Challenges and Mitigation Strategies 16th Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 1 November 2017 London 0 Outline 1. Epidemiology 2. Challenges and Mitigation strategies SIAs Surveillance Routine Immunization 3. Summary and way forward 1 Epidemiology 2 Polio Viruses in Nigeria, 2015-2017 Past 24 months Past 12 months 3 Nigeria has gone 13 months without Wild Polio Virus and 11 months without cVDPV2 13 months without WPV 11 months – cVDPV2 4 Challenges and Mitigation strategies 5 SIAs 6 Before the onset of the Wild Polio Virus Outbreak in July 2016, there were several unreached settlements in Borno Borno Accessibility Status by Ward, March 2016 # of Wards in % Partially LGAs % Fully Accessible % Inaccessible LGA Accessible Abadam 10 0% 0% 100% Askira-Uba 13 100% 0% 0% Bama 14 14% 0% 86% Bayo 10 100% 0% 0% Biu 11 91% 9% 0% Chibok 11 100% 0% 0% Damboa 10 20% 0% 80% Dikwa 10 10% 0% 90% Gubio 10 50% 10% 40% Guzamala 10 0% 0% 100% Gwoza 13 8% 8% 85% Hawul 12 83% 17% 0% Jere 12 50% 50% 0% Kaga 15 0% 7% 93% Kala-Balge 10 0% 0% 100% Konduga 11 0% 64% 36% Kukawa 10 20% 0% 80% Kwaya Kusar 10 100% 0% 0% Mafa 12 8% 0% 92% Magumeri 13 100% 0% 0% Maiduguri 15 100% 0% 0% Marte 13 0% 0% 100% Mobbar 10 0% 0% 100% Monguno 12 8% 0% 92% Ngala 11 0% 0% 100% Nganzai 12 17% 0% 83% Shani 11 100% 0% 0% State 311 41% 6% 53% 7 Source: Borno EOC Data team analysis Four Strategies were deployed to expand polio vaccination reach and increase population immunity in Borno state SIAs RES2 RIC4 Special interventions 12 -

Kano Feel Free Download

Kano feel free download click here to download Kano Feel Free () - file type: mp3 - download - bitrate: kbps. Download Kano Feel Free mp3 for free. kano feel free video and listen to kano feel free feat damon albarn later archive is one of the most popular song. Always visit www.doorway.ru to listen and download your favorite songs. WMG Feel Free (video). See more at www.doorway.ru Kano and Damon Albarn perform Feel Free on Later with Jools Missing: download. So the stories told in London Town, From the east and the west we come, And we'll all feel better tomorrow Missing: download. Kano Typeface (Free Font) Kano typeface designed and shared by Frederick Lee. Kano more suitable for your design work. "Kano" is an uppercase and lowercase. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Kano – Kano - Feel Good Inc (Gorillaz Cover) (Radio 1 Live Lounge) for free. Discover more music, gig and concert tickets, videos, lyrics, free downloads and MP3s, and photos with the largest catalogue online at www.doorway.ru £ to buy (VAT included if applicable). Listen Now · Go Unlimited. Start your day free trial. Amazon Music Unlimited subscribers can play 40 million songs, thousands of playlists and ad-free stations including new releases. Learn More · Buy song £ · Add to MP3 Basket · Song in MP3 Basket View MP3 Basket. ALUCINANDO KANO album SWEET RHYTHM kano records mp3 from: www.doorway.ru size: MB - duration: - bitrate: kbps download - listen close - lyrics. feel free kano mp3 from: www.doorway.ru size: KB - duration: - bitrate: kbps download - listen close - lyrics. -

Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard

The case of Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard Contact: Source: CIA factbook Laurent Fourchard Institut Francais de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA), University of Ibadan Po Box 21540, Oyo State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] INTRODUCTION: THE CITY A. URBAN CONTEXT 1. Overview of Nigeria: Economic and Social Trends in the 20th Century During the colonial period (end of the 19th century – agricultural sectors. The contribution of agriculture to 1960), the Nigerian economy depended mainly on agri- the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell from 60 percent cultural exports and on proceeds from the mining indus- in the 1960s to 31 percent by the early 1980s. try. Small-holder peasant farmers were responsible for Agricultural production declined because of inexpen- the production of cocoa, coffee, rubber and timber in the sive imports and heavy demand for construction labour Western Region, palm produce in the Eastern Region encouraged the migration of farm workers to towns and and cotton, groundnut, hides and skins in the Northern cities. Region. The major minerals were tin and columbite from From being a major agricultural net exporter in the the central plateau and from the Eastern Highlands. In 1960s and largely self-sufficient in food, Nigeria the decade after independence, Nigeria pursued a became a net importer of agricultural commodities. deliberate policy of import-substitution industrialisation, When oil revenues fell in 1982, the economy was left which led to the establishment of many light industries, with an unsustainable import and capital-intensive such as food processing, textiles and fabrication of production structure; and the national budget was dras- metal and plastic wares.