Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin Spring 2010

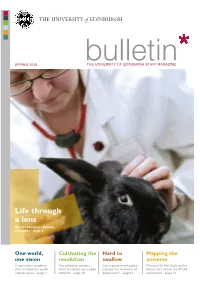

THE UNIVE RSIT Y of EDINBU RGH SPRING 2010 bTHE UNIVuERSITY OlF ElDINeBURGH StTAFFiMAn GAZINE Life through a lens Our Vet School is captured on camera – page 8 One world, Cultivating the Hard to Mapping the one vision revolution swallow universe A new health academy The collective campus Can a government policy Physicist Dr Phil Clark on the aims to make the world effort to reduce our carbon improve the treatment of University’s role in the ATLAS a better place – page 7 footprint – page 10 depression? – page14 experiment – page 17 advertisement... “I want to help future generations of researchers continue our work.” THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH CAMPAIGN Kath Melia is Professor of Nursing Studies role in developing nursing at Edinburgh, at the University of Edinburgh. This year, had remembered the University in her will, she took the significant step of making a gift a gesture which is helping the important in her will to help continue the work and work we are doing today. This has inspired research of the University. me to do the same.” Kath explains, “I was touched to find that a By making a gift in your will, you, too, former colleague, who had played a pivotal can help shape the future of Edinburgh. Legacies from former members of staff at the University of If you would like more information on leaving a legacy to the Edinburgh support teaching, facilities and research across the University of Edinburgh or if you have already done so, Schools and Colleges. We are very grateful for this commitment. please contact our Legacy team in confidence: This support is vital to help this work continue and legacies, big email: [email protected] and small, can make a difference to a research project or help [email protected] support a junior researcher present their work for the first time. -

Childhood Autism: Its Diagnosis, Nature, and Treatment

Archives ofDisease in Childhood 1991; 66: 737-741 737 CURRENT TOPIC Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.66.6.737 on 1 June 1991. Downloaded from Childhood autism: its diagnosis, nature, and treatment Sula Wolff Leo Kanner,I although not the first to describe epidemiological prevalence studies have found this serious and intriguing developmental dis- two to four autistic children in every 10 000, order of early childhood,2 so precisely captured more if severely retarded children with autistic its essential features that the clinical account of features are included.2 his first 11 cases has never been bettered. The There have been several long term follow up salient characteristics he mentioned were an studies of autistic clinic attenders but only two 'extreme autistic aloneness' from the beginning of total population samples.5 6 Gillberg and of life, delay and abnormality in language Steffenburg followed up 23 autistic children and acquisition with echolalia and pronomial rever- 23 with 'other psychoses', often associated with sal, and 'an obsessional desire for the mainte- organic handicapping conditions, to the age of nance of sameness' in the presence of islets of 16-23 years.6 In 17% of both groups outcome normality, in particular an excellent rote mem- was 'good' or 'fair', and in 44% of autistic and ory. He saw the primary deficit as an inborn dis- 70% of other psychotic children it was 'poor' or turbance of affective contact and later described 'very poor'. Among this still quite young group similar, although very mild features of emotio- of subjects only one was self supporting, 23 nal coldness and obsessionality in the parents. -

Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man Jeffrey Erik Berry Bates College, [email protected]

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects Spring 5-2012 Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man Jeffrey Erik Berry Bates College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Berry, Jeffrey Erik, "Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man" (2012). Honors Theses. 10. http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/10 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Departments of History and of German & Russian Studies Bates College In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Jeffrey Berry Lewiston, Maine 23 March 2012 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis advisors, Professor Craig Decker from the Department of German and Russian Studies and Professor Jason Thompson of the History Department, for their patience, guidance and expertise during this extensive and rewarding process. I also would also like to extend my sincere gratitude to the people who will be participating in my defense, Professor John Cole of the Bates College History Department, Profesor Raluca Cernahoschi of the Bates College German Department, and Dr. Richard Blanke from the University of Maine at Orno History Department, for their involvement during the culminating moment of my thesis experience. Finally, I would like to thank all the other people who were indirectly involved during my research process for their support. -

Does Autism Merit Belief? Developing an Account of Scientific Realism for Psychiatry

Sam Fellowes, BSc, MA Does autism merit belief? Developing an account of scientific realism for psychiatry Ph.D. Philosophy March 2016 1 Abstract Sam Fellowes, BSc, MA Does autism merit belief? Developing an account of scientific realism for psychiatry Ph.D. Philosophy March 2016 The PhD outlines criteria under which a psychiatric classification merits belief and, as a case study, establishes that autism merits belief. Three chapters respond to anti- realist arguments, three chapters establish conditions under which psychiatric classifications merit belief. Chapter one addresses the pessimistic meta-induction. I historically analyse autism to show there has been sufficient historical continuity to avoid the pessimistic meta induction. Chapter two considers arguments from underdetermination. I consider the strongest candidate for an alternative to autism, classificatory changes which occurred between 1980 and 1985. I argue this does not constitute underdetermination because those changes were methodologically and evidentially flawed. Chapter three considers theory-ladenness. I consider the two strongest candidates for background theories which might have a negative epistemic effect (cognitive psychology and psychoanalysis). I show these have little influence on what symptoms are formulated or how symptoms are grouped together. Chapter four argues against psychiatric classifications as natural kinds and against notions that inductive knowledge of psychiatric classifications requires robust causes. I outline psychiatric classifications as scientific laws. They are high level idealised models which guide construction of lower level, more specific, models. This opens alternative routes to belief for psychiatric classification lacking robust causes. Chapter five shows that psychiatric classifications can set relevant populations for deriving statistically significant symptoms. The same behaviour can count as statistically significant for one psychiatric classification but not another. -

H-Diplo ROUNDTABLE XXI-14

H-Diplo ROUNDTABLE XXI-14 Edith Sheffer, Asperger’s Children: The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna. New York: W.W. Norton, 2018. ISBN: 9780393609646. 15 November 2019 | https://hdiplo.org/to/RT21-14 Roundtable Editors: Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins and Diane Labrosse | Production Editor: George Fujii Contents Introduction by Benjamin P. Hein, Brown University, Samuel Clowes Huneke, George Mason University, and Michelle Lynn Kahn, University of Richmond .........................................................................................................................................................................................................2 Review by Kathryn Brackney, Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies ............................................................................................5 Review by David Freis, University of Münster .......................................................................................................................................................................8 Review by Dagmar Herzog, Graduate Center, City University of New York .................................................................................................... 11 Response by Edith Sheffer, University of California, Berkeley ................................................................................................................................... 14 H-Diplo Roundtable XXI-14 Introduction by Benjamin P. Hein, Brown University, Samuel Clowes Huneke, George Mason University, and Michelle Lynn Kahn, -

Neurotribes 20/20

Neurotribes 20/20, (March 13, 1992). The Street Where They Lived. Part 1, ABC News 20/20, (March 20, 1992.). The Street Where They Lived. Part 2, ABC News A Tribute to Eric Schopler (1927–2006). http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D_THeWH0ox4 Adams, G. S. and Kanner, L. (1926). General Paralysis among the North American Indians: A Contribution to Racial Psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry Aichhorn, A. (1965). Wayward Youth. New York, NY: Penguin Books repr. ed. Aldiss, B. W. (1995). The Detached Retina: Aspects of SF and Fantasy. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press Allison, H. (1987). Perspectives on a Puzzle Piece. National AutisticSociety Aly, G. Chroust, P. and Pross, C. (1994). Cleansing the Fatherland: Nazi Medicine and Racial Hygiene, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press American Journal of Psychiatry, (1939). News and Notes. 96(3). 736–46 American Philosophical Society. Eugenics Record Office Records, 1670–1964 American-Austrian Foundation. The Medical Club—Billrothhaus: Epoch-Making Lectures in Medical History.” http://www.aaf-online.org/ Anderson v. W. R. Grace: Background/About the Case, Seattle University School of Law. http://www.law.seattleu.edu/centers-and-institutes/films-for-justice-institute/lessons-from- woburn/about-the-case Anderson, E. L. (1988). Behavioral Treatment of Autism. Documentary by Edward L. Anderson and Robert Aller. Focus International Andreas Ströhle et al. (2008.). Karl Bonhoeffer (1868–1948). American Journal of Psychiatry Andrews, J. (1997). The History of Bethlem. (pp. 272). New, York: Psychology Press Angres, R. (Oct. 1980). Who, Really, Was Bruno Bettelheim? Commentary Anthony, E. J. (1958). An Experimental Approach to the Psychopathology of Childhood Autism. -

Hans Asperger, National Socialism, and “Race Hygiene” in Nazi-Era Vienna Herwig Czech

Czech Molecular Autism _#####################_ https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-018-0208-6 RESEARCH Open Access Hans Asperger, National Socialism, and “race hygiene” in Nazi-era Vienna Herwig Czech Abstract Background: Hans Asperger (1906–1980) first designated a group of children with distinct psychological characteristics as ‘autistic psychopaths’ in 1938, several years before Leo Kanner’s famous 1943 paper on autism. In 1944, Asperger published a comprehensive study on the topic (submitted to Vienna University in 1942 as his postdoctoral thesis), which would only find international acknowledgement in the 1980s. From then on, the eponym ‘Asperger’s syndrome’ increasingly gained currency in recognition of his outstanding contribution to the conceptualization of the condition. At the time, the fact that Asperger had spent pivotal years of his career in Nazi Vienna caused some controversy regarding his potential ties to National Socialism and its race hygiene policies. Documentary evidence was scarce, however, and over time a narrative of Asperger as an active opponent of National Socialism took hold. The main goal of this paper is to re-evaluate this narrative, which is based to a large extent on statements made by Asperger himself and on a small segment of his published work. Methods: Drawing on a vast array of contemporary publications and previously unexplored archival documents (including Asperger’s personnel files and the clinical assessments he wrote on his patients), this paper offers a critical examination of Asperger’s life, politics, and career before and during the Nazi period in Austria. Results: Asperger managed to accommodate himself to the Nazi regime and was rewarded for his affirmations of loyalty with career opportunities. -

Henry Walton. in Memoriam

IN MEMORIAM Henry Walton. In Memoriam Andrzej Wojtczak El 13 de julio de 2012, la educación médica mundial On July 13th 2012 the world medical education lost Exdirector del International Institute for Medical Education perdió uno de sus más preeminentes educadores a one of it’s most prominent educators at the age of 88 (IME). la edad de 88 años, el profesor Henry Walton. En su – Professor Henry Walton. He definitely deserves the Expresidente de la Association figura debemos reconocer a uno de los padres fun- recognition, and position, of one of the founding fa- for Medical Education in Europe dadores de la educación médica contemporánea. thers of contemporary medical education. (AMEE). Nacido en Sudáfrica, se graduó en Medicina en Born in South Africa, he graduated from the E-mail: la Facultad de Medicina de Ciudad del Cabo y des- medical school in Cape Town, and after special [email protected] pués de un especial entrenamiento en Londres y training in London and New York in 1967, he be- © 2012 Educación Médica Nueva York en 1967, llegó a ser catedrático de psi- came Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Ed- quiatría en la Universidad de Edimburgo. En el año inburgh. In 1986 he took the Chair of International 1986 accedió a la Cátedra de Educación Médica In- Medical Education at the University of Edinburgh. ternacional de la referida universidad. For many of us he will be remembered as a Por muchos de nosotros será recordado como el founder and first President of the Association for fundador y primer presidente de la Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE) that was Medical Education in Europe established in 1972. -

Leben Und Werk Des Jüdischen Wissenschaftlers Und Kinderarztes Erich Benjamin

Institut für Geschichte und Ethik der Medizin der Technischen Universität München (Vorstand: Univ.-Prof. Dr. J. C. Wilmanns) Leben und Werk des jüdischen Wissenschaftlers und Kinderarztes Erich Benjamin * 1880 in Berlin † 1943 in Baltimore Susanne Oechsle Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät für Medizin der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Medizin genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr. D. Neumeier Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr. J. C. Wilmanns 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr. A. Neiß 3. Univ.-Prof. Dr. W. Arnold Die Dissertation wurde am 30.06.2003 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät für Medizin am 17.03.2004 angenommen. III Je weiser und besser ein Mensch ist, umso mehr Gutes bemerkt er in den Menschen. B. Pascal Diese Arbeit widme ich meiner lieben Schwester Sabine. V Abbildung 1: Erich Benjamin, etwa Mitte der 1930er Jahre. Quelle: Jäckle (1988) S. 52. Verzeichnisse VII Inhaltsverzeichnis I. Einleitung.......................................................................................................... 1 II. Quellenlage....................................................................................................... 3 1. Stand der Forschung.................................................................................... 3 2. Spurensuche ................................................................................................ 3 2.1 Spuren zu Benjamins beruflichem Werdegang .......................................................... -

'Non-Complicit: Revisiting Hans Asperger's Career in Nazi-Era Vienna'

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019) 49:3883–3887 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04106-w RESPONSE Response to ‘Non‑complicit: Revisiting Hans Asperger’s Career in Nazi‑era Vienna’ Herwig Czech1,2 Published online: 13 June 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract In her recent paper ‘Non-complicit: Revisiting Hans Asperger’s Career in Nazi-era Vienna,’ Dean Falk claims to refute what she calls ‘allegations’ about Hans Asperger’s role during National Socialism documented in my 2018 paper ‘Hans Asperger, National Socialism, and “race hygiene” in Nazi-era Vienna’ and Edith Shefer’s book ‘Asperger’s Children.’ Falk’s paper, which relies heavily on online translation software, does not contain a single relevant piece of new evidence, but abounds with mistranslations, misrepresentations of the content of sources, and basic factual errors, and omits everything that does not support the author’s agenda of defending Hans Asperger’s record. The paper should never have passed peer review and, in view of the academic credibility of all parties concerned, it should be retracted. Keywords Asperger syndrome · Hans Asperger · National socialism · Nazi ‘euthanasia · Nazi-era Vienna · Therapeutic pedagogy (Heilpädagogik) In her paper ‘Non-complicit: Revisiting Hans Asperger’s on online translation tools), and a refusal to seriously engage Career in Nazi-era Vienna’, evolutionary anthropologist with the evidence presented in my paper by omitting every- Dean Falk claims to refute what she calls ‘allegations’ thing that does not support the author’s manifest agenda of raised against Asperger (Czech 2018; Shefer 2018) ‘with defending Hans Asperger’s record. -

Introduction Chapter 1: Asperger and I

notes INTRODUCTION p. ix “a devastating handicap ...” Uta Frith, “Asperger and His Syndrome,” in Frith, 1991,p.5. p. ix “Paucity of empathy; naive, inappropriate, one-sided social inter- action ...” Klin, Ami, and Fred Volkmar, “Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome,” Yale University Child Study Center, July/August 8–9, 1994. p. xi “the first plausible variant to crystallize out of the autism spectrum ...” Uta Frith, “Asperger and His Syndrome,” in Frith, 1991,p.5. p. xi “More than anything, ADD represents ...” DeGrandpre, 2000,p.39. p. xiii The exchange between Diller and Greene can be read in the archives of Salon magazine (http://archive.salon.com). The fireworks began with Diller’s review of Greene’s The Explosive Child on July 18, 2001, and Greene’s response on July 19. p. xvi “The path to understanding ...” Hans Asperger as quoted in Klin et al, 2000, p. xii. CHAPTER 1: ASPERGER AND I p. 2 “I like the scenery. I like the schedules.” This and other quotations in this chapter by and about Darius McCollum are from “Irresistible Lure of Subways Keeps Landing Impostor in Jail,” by Dean E. Murphy, The New York Times, August 24, 2000,p.A1. p. 5 “Autism as a subject touches on the deepest questions of ontology ...” Sacks, 1996,p.246. p. 6 “Almost all of my social contacts ...” Sacks, 1996,p.261. p. 8 “America is the first society to be totally dominated ...” Postman, 1994,p. 145. p. 9 “What, after all, is normality?” Uta Frith, “Asperger and His Syn- drome,” in Frith, 1991,p.23. -

Possible Aetiological Factors in Childhood Leukaemia

Asperger's sydrome 179 acceptance of the children's difficulties as constitutional: same services as well functioning autistic children. The neither wilful nor parent engendered. In later life, many of more intelligent and less obviously handicapped Asperger/ them had good work achievements and many married, but schizoid children require above all to be identified as consti- Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.66.2.179 on 1 February 1991. Downloaded from their overall work adjustment, their heterosexual adjust- tutionally impaired.14 Their special make up needs to be ment, and their psychiatric state were worse than those of understood. They may also need special arrangements other referred children grown up (S Wolff, to be published). made, particularly at school, in the knowledge that in later These children resembled the schizotypal children descri- life when pressures for conformity are less than during the bed by Nagy and Szatmari,1° and their difficulties certainly school years, many will be able to find their social niche, overlapped with those of the patients of Wing and Tantam. and a few to develop their rather exceptional gifts. But whether they too should be included in an 'autistic spec- SULA WOLFF trum' will depend on the results of more definitive genetic University Department of Psychiatry, studies. The Kennedy Tower, For this reason, the arguments put forward by Professor Royal Edinburgh Hospital, Cox in this issue against a global diagnosis of autism,"1 12 Morningside Park, and in defence of a distinct diagnostic category of Asperger's Edinburgh EJO SHF syndrome, although based on Wing's rather narrow defini- 1 Asperger H.