Copy of WITNESS SEMINAR FINAL 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Best Way to Assess the Degree of Civilization of Any Society Is To

ALC037 Alcohol etc. (Scotland) Bill Forrester Cockburn Children and a Civilized Scottish Society The best way to assess the degree of civilization of any society is to examine the quality of care which that society provides for the health, welfare and education of its children. In order to achieve optimal child health, it is imperative that the mothers are healthy, understand the needs of their unborn and newborn children and have the appropriate environment for the safe delivery and rearing of their children within a supportive family and community. In Scotland increasing abuse of alcohol and other drugs has placed a large number of children at risk of poor health and born to fail. In this essay I shall concentrate on the risks to the unborn child and the infant after birth. Alcohol damage before birth Probably the first relevant scientific observations were made by Sullivan in 1899. He examined the results of 600 pregnancies of 120 alcoholic women in a Liverpool prison population and found that the infant mortality and stillbirth rate was two and a half times that of their non-alcoholic female relatives. He also showed that the forced abstinence of imprisonment improved the pregnancy outcome. There was parliamentary comment in the UK at that time but little further scientific evidence until the report from Lemoine et al in 1969 which described 127 children with characteristic facial abnormalities and poor growth. The same features were recognised in North America and Canada in the early 1970’s. Since then many other countries including Scotland have identified the problems now known as the fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) in the infants of mothers drinking alcohol during pregnancy. -

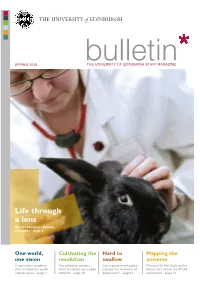

Bulletin Spring 2010

THE UNIVE RSIT Y of EDINBU RGH SPRING 2010 bTHE UNIVuERSITY OlF ElDINeBURGH StTAFFiMAn GAZINE Life through a lens Our Vet School is captured on camera – page 8 One world, Cultivating the Hard to Mapping the one vision revolution swallow universe A new health academy The collective campus Can a government policy Physicist Dr Phil Clark on the aims to make the world effort to reduce our carbon improve the treatment of University’s role in the ATLAS a better place – page 7 footprint – page 10 depression? – page14 experiment – page 17 advertisement... “I want to help future generations of researchers continue our work.” THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH CAMPAIGN Kath Melia is Professor of Nursing Studies role in developing nursing at Edinburgh, at the University of Edinburgh. This year, had remembered the University in her will, she took the significant step of making a gift a gesture which is helping the important in her will to help continue the work and work we are doing today. This has inspired research of the University. me to do the same.” Kath explains, “I was touched to find that a By making a gift in your will, you, too, former colleague, who had played a pivotal can help shape the future of Edinburgh. Legacies from former members of staff at the University of If you would like more information on leaving a legacy to the Edinburgh support teaching, facilities and research across the University of Edinburgh or if you have already done so, Schools and Colleges. We are very grateful for this commitment. please contact our Legacy team in confidence: This support is vital to help this work continue and legacies, big email: [email protected] and small, can make a difference to a research project or help [email protected] support a junior researcher present their work for the first time. -

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health British Paediatric Surveillance Unit

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health British Paediatric Surveillance Unit 14th Annual Report 1999/2000 The British Paediatric Surveillance Unit always welcomes invitations to give talks describing the work of the Unit and makes every effort to respond to these positively. Enquiries should be directed to our office. The Unit positively encourages recipients to copy and circulate this report to colleagues, junior staff and medical students. Additional copies are available from our office, to which any enquiries should be addressed. Published September 2000 by the: British Paediatric Surveillance Unit A unit within the Research Division of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health 50 Hallam Street London W1W 6DE Telephone: 44 (0) 20 7307 5680 Facsimile: 44 (0) 20 7307 5690 E-mail: [email protected] Registered Charity No. 1057744 ISBN 1 900954 48 6 © British Paediatric Surveillance Unit British Paediatric Surveillance Unit - 14 Annual Report 1999-2000 Compiled and edited by Richard Lynn, Angus Nicoll, Jugnoo Rahi and Chris Verity Membership of Executive Committee 1999/2000 Dr Christopher Verity Chairman Dr Angus Clarke Co-opted Professor Richard Cooke Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Research Division Dr Patricia Hamilton Co-opted Professor Peter Kearney Faculty of Paediatrics, Royal College of Physicians of Ireland Dr Jugnoo Rahi Medical Adviser Dr Ian Jones Scottish Centre for Infection and Environmental Health Dr Christopher Kelnar Co-opted Dr Gabrielle Laing Co-opted Mr Richard Lynn Scientific Co-ordinator -

A Critical Analysis of Medical Opinion Evidence in Child Homicide Cases

A critical analysis of medical opinion evidence in child homicide cases Sharmila Betts B.A. (Hons.), University of Sydney, 1985 M. Psychol., University of Sydney, 1987 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Law, The University of New South Wales (Sydney). i ii iii Acknowledgements No way of thinking or doing, however ancient, can be trusted without proof. Henry David Thoreau I am a Clinical Psychologist practicing since 1987. My time at a tertiary level Child Protection Team at The Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick, Australia brought to my attention the pivotal role of medical opinion evidence in establishing how children sustained injuries, which were sometimes fatal. This thesis began in a Department of Psychology, but I transferred to a Law Faculty. Though I am not a lawyer, the thesis endeavours to examine medico-legal and psychological aspects of sudden unexplained infant deaths. It sets itself the task of addressing important questions requiring rigorous and critical analysis to ensure accuracy and justice is achieved. I hope my thesis sheds light on this complex issue. Gary Edmond has been a mentor, guide and staunch critic. I am deeply grateful that he trusted a novice to navigate this perplexing field of inquiry. Emma Cunliffe has provided clarity in an area shrouded in uncertainty. Their patience, support and faith have enabled me to crystalise and formulate my fledgling insights into a dissertation. I am indebted to Natalie Tzovaras, Monique Ross, Katie Poidomani, and Janet Willinge for their administrative support. My husband, Grant, posed the question that started my journey - ‘how do doctors know the injuries were deliberately inflicted?’ Through my many doubts and fears, he iv maintained a trust in my ability to address this question and helped me return time and again to the seemingly overwhelming task before me. -

Italian Imago 02-01-310 455.Pdf

Autorizzazione del Tribunale di Reggio Calabria del 5 Settembre 2019 © 2020 SPG REGGIO CALABRIA Tutti i diritti riservati WILFRED RUPRECHT BION: VITA, PENSIERO, OPERE PASQUALE LUCA QUIETO – GABRIELE ROMEO WILFRED RUPRECHT BION: VITA, PENSIERO, OPERE LA GRUPPOANALISI MATHURA (UTTAR PRADESH, ALLORA REGNO UNITO, OGGI INDIA), 8 SETTEMBRE 1897 OXFORD (SOUTH EAST ENGLAND, REGNO UNITO), 8 NOVEMBRE 1979 TRADUZIONE IN INGLESE DI PASQUALE LUCA QUIETO – GABRIELE ROMEO WILFRED RUPRECH BION: LIFE, THINKING, WORKS THE GROUPE–ANALYSIS AUTORI E TRADUTTORI Pasquale Luca Quieto, Psicologo, Psicoanalista, Gruppoanalista, Membro della Società di Psicoanalisi e Gruppoanalisi Italiana. Gabriele Romeo, Medico, Psicologo, Psicoanalista, Presidente della Società Scientifica di Psicoanalisi e Gruppoanalisi Italiana, Caporedattore di Italian Imago, Docente, Analista Didatta e Supervisore, Coordinatore Didattico della Scuola di Specializzazione in Psicoterapia Psicoanalitica e Gruppoanalitica di Reggio Calabria. AUTHORS AND TRANSATORS Pasquale Luca Quieto, Psychoanalyst, Groupanalyst, member of the Società di Psicoanalisi e Gruppoanalisi Italiana. Gabriele Romeo, M.D., Ph.D., Psychoanalyst, President of the Società di Psicoanalisi e Gruppoanalisi Italiana, Chief Editor of Italian Imago, Teacher, Didactic and Supervisor Analyst, Didactic Coordinator of the Scuola di Specializzazione in Psicoterapia Psicoanalitica e Gruppoanalitica of Reggio Calabria. 310 PASQUALE LUCA QUIETO – GABRIELE ROMEO Wilfred Ruprecht Bion Mathura (Uttar Pradesh, allora Regno Unito, oggi India), -

Attachment, Locus of Control, and Romantic Intimacy in Adult

ATTACHMENT, LOCUS OF CONTROL, AND ROMANTIC INTIMACY IN ADULT CHILDREN OF ALCOHOLICS: A CORRELATIONAL INVESTIGATION by Raffaela Peter A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Education in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida December 2012 Copyright Raffaela Peter 2012 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my family members and friends for their continuous support and understanding during this process of self-exploration which oftentimes called for sacrifices on their part. Not to be forgotten is the presence of a very special family member, Mr. Kitty, who silently and patiently witnessed all colors and shapes of my affective rainbow. Val Santiago Stanley has shown nothing but pure, altruistic friendship for which I will be forever grateful. The appreciation is extended to Val’s Goddesses Club and its members who passionately give to others in the community. Many thanks go out to Jackie and Julianne who, with true owl spirit and equipped with appropriate memorabilia, lent an open ear and heart at all times. Thank you to my committee who provided me with guidance and knowledge throughout my journey at Florida Atlantic University. Most of them I have known for nearly a decade, a timeframe that has allowed me to grow as an individual and professional. To Dr. Paul Ryan Peluso, my mentor and fellow Avenger, thank you for believing in me and allowing me to “act as if”; your metaphors helped me more than you will ever know. You are a great therapist and educator, and I admire your dedication to the profession. -

PKU): Screening and Management

Consensus Development Conference on Phenylketonuria (PKU): Screening and Management October 16–18, 2000 William H. Natcher Conference Center National Institutes of Health Bethesda, Maryland Sponsored by: ¤ National Institute of Child Health and Human Development ¤ NIH Office of Medical Applications of Research ¤ Cosponsored by: ¤ National Human Genome Research Institute ¤ National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases ¤ National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke ¤ National Institute of Nursing Research ¤ NIH Office of Rare Diseases ¤ Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration ¤ Contents Introduction......................................................................................................................................1 Agenda .............................................................................................................................................5 Panel Members...............................................................................................................................11 Speakers .........................................................................................................................................13 Planning Committee.......................................................................................................................15 Abstracts.........................................................................................................................................17 I. Overview Phenylketonuria: -

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

Theorists and Theories of Child Development Learner Support Handbook

Theorists and Theories of Child Development Learner Support Handbook Supporting the development of your career Introduction This information guide is designed to support the knowledge and understanding of child development, in particular the theories and theorists behind these. It details it looks at the seven most popular theorists and the research carried out by them to highlight the many fascinating ways in which children develop and learn Child development theories focus on explaining how children change and grow over the course of childhood. Such theories centre on various aspects of development including social, emotional and cognitive growth. The study of human development is a rich and varied subject. We all have personal experience with development, but it is sometimes difficult to understand: How and why people grow, learn, and act as they do. Why do children behave in certain ways? Is their behaviour related to their age, family relationships, or individual temperament? Developmental psychologists strive to answer such questions as well as to understand, explain, and predict behaviours that occur throughout the lifespan. In order to understand human development, a number of different theories of child development have arisen to explain various aspects of human growth. The guide covers the following theorists and details each of their theories: 1. Freud’s Psychosexual Developmental Theory 2. Erikson's Psychosocial Developmental Theory 3. Piaget's Cognitive Developmental Theory 4. Bowlby's Attachment Theory 5. Bandura's Social Learning Theory 6. Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory Supporting the development of your career Child Development Theories: A Background Theories of development provide a framework for thinking about human growth and learning. -

Putting the Baby in the Bath Water: Give Priority to Prevention and First 1,001 Days

Collective supplemental evidence to the Scottish Parliament about the Children and Young People Bill Putting the Baby in the Bath Water: Give priority to prevention and first 1,001 days 1. This document offers the shared views and recommendations of a wide variety of organisations and individuals (listed at the end). All the signatories appreciate the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Government’s desire to enact legislation that will move our nation closer to becoming ‘the best place to grow up’. We all share that goal and understand that the Children and Young People Bill is the one major legislative proposal since the Scottish Parliament was created that directly focuses on children’s rights, children’s services and the wellbeing of children and young people. It represents a crucial and welcome window of opportunity. We propose five additional ways to make the most of this opportunity. 2. It is a complex Bill of many parts. Our view is that when seen as a ‘jigsaw puzzle’, one fundamental piece is missing. The Bill does not provide a robust statutory foundation for positive action during the first 1,001 days of life (from pre-birth to age 2). 3. There is a disconnect between the case made for the Bill in its accompanying Policy Memorandum and actual provisions proposed within the Bill. We think this Bill, as introduced, should be amended to connect the dots between its Policy Memorandum and the Bill itself. Its excellent analysis of the wisdom of investing in the earliest years through preventative spending is not reflected in what this legislation actually proposes to do. -

Childhood Autism: Its Diagnosis, Nature, and Treatment

Archives ofDisease in Childhood 1991; 66: 737-741 737 CURRENT TOPIC Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.66.6.737 on 1 June 1991. Downloaded from Childhood autism: its diagnosis, nature, and treatment Sula Wolff Leo Kanner,I although not the first to describe epidemiological prevalence studies have found this serious and intriguing developmental dis- two to four autistic children in every 10 000, order of early childhood,2 so precisely captured more if severely retarded children with autistic its essential features that the clinical account of features are included.2 his first 11 cases has never been bettered. The There have been several long term follow up salient characteristics he mentioned were an studies of autistic clinic attenders but only two 'extreme autistic aloneness' from the beginning of total population samples.5 6 Gillberg and of life, delay and abnormality in language Steffenburg followed up 23 autistic children and acquisition with echolalia and pronomial rever- 23 with 'other psychoses', often associated with sal, and 'an obsessional desire for the mainte- organic handicapping conditions, to the age of nance of sameness' in the presence of islets of 16-23 years.6 In 17% of both groups outcome normality, in particular an excellent rote mem- was 'good' or 'fair', and in 44% of autistic and ory. He saw the primary deficit as an inborn dis- 70% of other psychotic children it was 'poor' or turbance of affective contact and later described 'very poor'. Among this still quite young group similar, although very mild features of emotio- of subjects only one was self supporting, 23 nal coldness and obsessionality in the parents. -

Public Health Advocating for Children's Health: a US and UK Perspective

180 Arch Dis Child 2001;85:180–182 Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.85.3.180 on 1 September 2001. Downloaded from Public health Advocating for children’s health: a US and UK perspective In this article we describe the diVering American and Brit- in advocacy and lobbying, while in the UK this role has ish approaches to child health advocacy by paediatricians been carried out behind the scenes and in a less “political” and paediatric organisations. In the USA, advocacy has a fashion. long history and is well established as an important In the 1860s, Job Lewis Smith, who is considered by function of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), some as a founder of American paediatrics, was a strong but the USA still has to achieve universal health care cov- advocate for child health. Among Smith’s many advocacy erage for children. In contrast, the UK has had universal issues was the high death rate of abandoned, illegitimate health care for children for more than 50 years and infants who were not breast fed. Because of his eVorts, wet individual paediatricians have spoken out for children. nurses were made available, significantly lowering the mor- However the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child bidity and mortality of these “foundlings”.2 Since 1985, the Health (RCPCH) adopted advocacy as a goal only in 1997. AAP Section on Community Pediatrics has recognised In our article we pose the following questions: Smith’s advocacy eVorts by presenting an annual award to + What is advocacy and why is it a task for a community paediatrician who has made significant con- paediatricians? tributions to child health through a community advocacy + In what ways can paediatricians act as advocates for eVort.