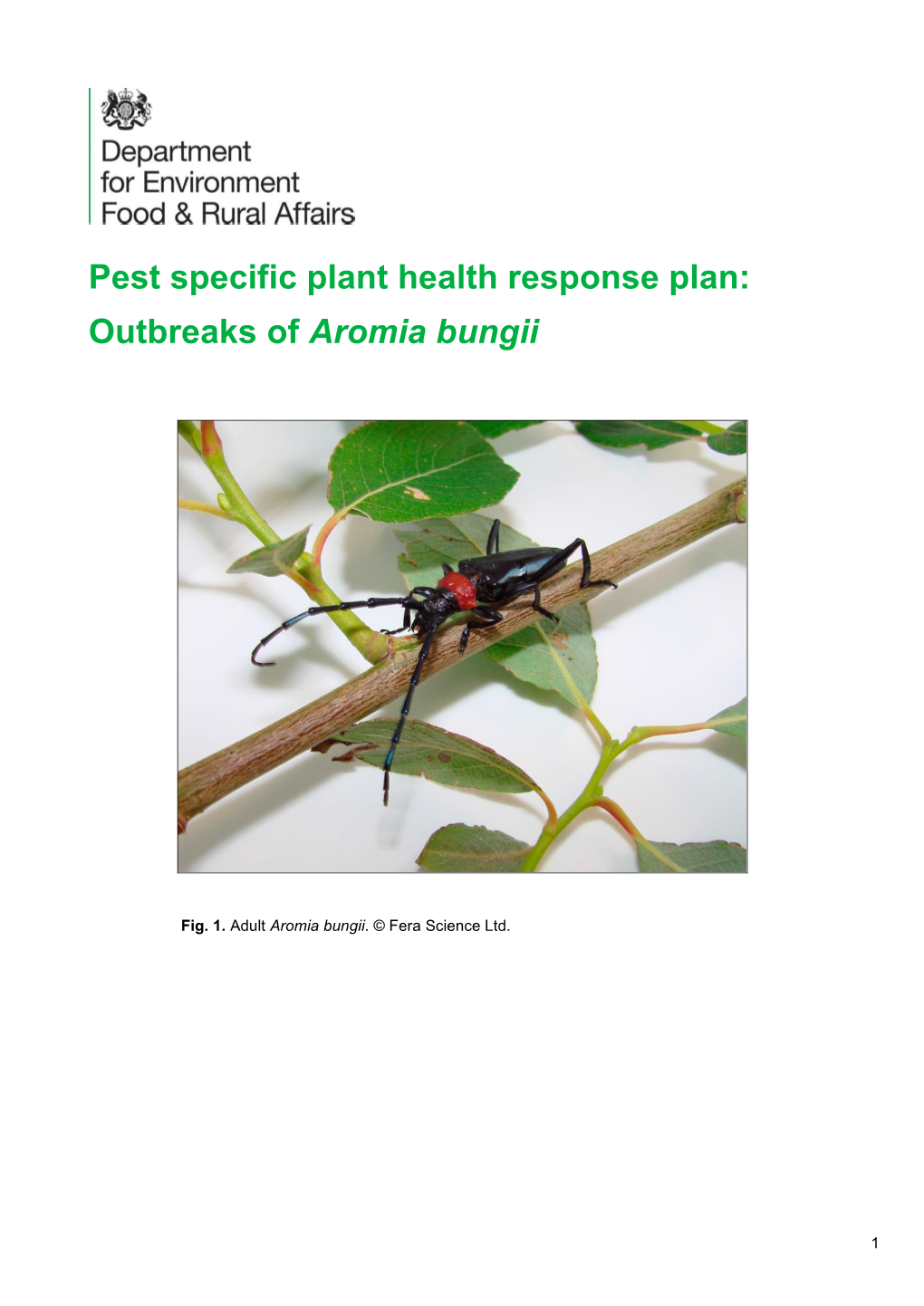

Aromia Bungii Red Necked Longhorn Beetle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LONGHORN BEETLE CHECKLIST - Beds, Cambs and Northants

LONGHORN BEETLE CHECKLIST - Beds, Cambs and Northants BCN status Conservation Designation/ current status Length mm In key? Species English name UK status Habitats/notes Acanthocinus aedilis Timberman Beetle o Nb 12-20 conifers, esp pine n ox-eye daisy and other coarse herbaceous plants [very recent Agapanthia cardui vr 6-14 n arrival in UK] Agapanthia villosoviridescens Golden-bloomed Grey LHB o f 10-22 mainly thistles & hogweed y Alosterna tabacicolor Tobacco-coloured LHB a f 6-8 misc deciduous, esp. oak, hazel y Anaglyptus mysticus Rufous-shouldered LHB o f Nb 6-14 misc trees and shrubs y Anastrangalia (Anoplodera) sanguinolenta r RDB3 9-12 Scots pine stumps n Anoplodera sexguttata Six-spotted LHB r vr RDB3 12-15 old oak and beech? n Anoplophora glabripennis Asian LHB vr introd 20-40 Potential invasive species n Arhopalus ferus (tristis) r r introd 13-25 pines n Arhopalus rusticus Dusky LHB o o introd 10-30 conifers y Aromia moschata Musk Beetle o f Nb 13-34 willows y Asemum striatum Pine-stump Borer o r introd 8-23 dead, fairly fresh pine stumps y Callidium violaceum Violet LHB r r introd 8-16 misc trees n Cerambyx cerdo ext ext introd 23-53 oak n Cerambyx scopolii ext introd 8-20 misc deciduous n Clytus arietus Wasp Beetle a a 6-15 misc, esp dead branches, posts y Dinoptera collaris r RDB1 7-9 rotten wood with other longhorns n Glaphyra (Molorchus) umbellatarum Pear Shortwing Beetle r o Na 5-8 misc trees & shrubs, esp rose stems y Gracilia minuta o r RDB2 2.5-7 woodland & scrub n Grammoptera abdominalis Black Grammoptera r r Na 6-9 -

Key to the Genera of Cerambycidae of Western North America

KEY TO THE GENERA OF THE CERAMBYCIDAE OF WESTERN NORTH AMERICA Version 030120 JAMES R. LaBONTE JOSHUA B. DUNLAP DANIEL R. CLARK THOMAS E. VALENTE JOSHUA J. VLACH OREGON DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Begin key Contributions and Acknowledgements James R. LaBonte, ODA (Oregon Department of Agriculture: Design and compilation of this identification aid. Joshua B. Dunlap: Acquisition of most of the images. Daniel R. Clark: Design input and testing. Thomas E. Valente, ODA: Design input and testing. Joshua J. Vlach, ODA: Design input and testing. Thomas Shahan, Thomas Valente, Steve Valley – additional images ODA: Use of the imaging system, the entomology museum, and general support. Our appreciation to USDA Forest Service and ODA for funding this project. Introduction Begin key This identification aid is a comprehensive key to the genera of western North American Cerambycidae (roundheaded or long- horned wood borers). It also includes several genera (and species) that are either established in the region or that are targets of USDA and other exotic cerambycid surveys. Keys to commonly trapped or encountered (based on ODA’s years of wood borer surveys) indigenous species are also included. *This aid will be most reliable west of the Rocky Mountains. It may not function well with taxa found in the desert West and east of the Rockies. This aid is designed to be used by individuals with a wide range of taxonomic expertise. Images of all character states are provided. Begin key Use of This Key: I This key is designed like a traditional dichotomous key, with couplets. However, PowerPoint navigational features have been used for efficiency. -

Biodiversity Assessment June 2020

North East Cambridge – A Biodiversity Assessment June 2020 MKA ECOLOGY North East Cambridge A Biodiversity Assessment June 2020 1 North East Cambridge – A Biodiversity Assessment June 2020 Site North East Cambridge Contents Project number 85919 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Client name / Address Cambridge City Council 1.1. Aims and objectives ....................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Site description and context........................................................................................... 3 Version 1.3. Legislation and policy .................................................................................................... 4 Date of issue Revisions number 2. NORTH EAST CAMBRIDGE ........................................................................................ 6 004 15 June 2020 Amendments to text and document accessibility 2.1. The geological setting .................................................................................................... 6 2.2. The ecological setting .................................................................................................... 6 003 02 April 2020 Updates regarding terrapins 2.3. The focus area ............................................................................................................. 10 002 20 February 2020 Updates to maps and text throughout 3. CONSTRAINTS .......................................................................................................... -

4 Reproductive Biology of Cerambycids

4 Reproductive Biology of Cerambycids Lawrence M. Hanks University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, Illinois Qiao Wang Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand CONTENTS 4.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 133 4.2 Phenology of Adults ..................................................................................................................... 134 4.3 Diet of Adults ............................................................................................................................... 138 4.4 Location of Host Plants and Mates .............................................................................................. 138 4.5 Recognition of Mates ................................................................................................................... 140 4.6 Copulation .................................................................................................................................... 141 4.7 Larval Host Plants, Oviposition Behavior, and Larval Development .......................................... 142 4.8 Mating Strategy ............................................................................................................................ 144 4.9 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 148 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. -

The Beetle Fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and Distribution

INSECTA MUNDI, Vol. 20, No. 3-4, September-December, 2006 165 The beetle fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and distribution Stewart B. Peck Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6, Canada stewart_peck@carleton. ca Abstract. The beetle fauna of the island of Dominica is summarized. It is presently known to contain 269 genera, and 361 species (in 42 families), of which 347 are named at a species level. Of these, 62 species are endemic to the island. The other naturally occurring species number 262, and another 23 species are of such wide distribution that they have probably been accidentally introduced and distributed, at least in part, by human activities. Undoubtedly, the actual numbers of species on Dominica are many times higher than now reported. This highlights the poor level of knowledge of the beetles of Dominica and the Lesser Antilles in general. Of the species known to occur elsewhere, the largest numbers are shared with neighboring Guadeloupe (201), and then with South America (126), Puerto Rico (113), Cuba (107), and Mexico-Central America (108). The Antillean island chain probably represents the main avenue of natural overwater dispersal via intermediate stepping-stone islands. The distributional patterns of the species shared with Dominica and elsewhere in the Caribbean suggest stages in a dynamic taxon cycle of species origin, range expansion, distribution contraction, and re-speciation. Introduction windward (eastern) side (with an average of 250 mm of rain annually). Rainfall is heavy and varies season- The islands of the West Indies are increasingly ally, with the dry season from mid-January to mid- recognized as a hotspot for species biodiversity June and the rainy season from mid-June to mid- (Myers et al. -

Transcriptome and Gene Expression Analysis of Rhynchophorus Ferrugineus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) During Developmental Stages

Transcriptome and gene expression analysis of Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) during developmental stages Hongjun Yang1,2, Danping Xu1, Zhihang Zhuo1,2,3, Jiameng Hu2 and Baoqian Lu4 1 College of Life Science, China West Normal University, Nanchong, Sichuan, China 2 Key Laboratory of Genetics and Germplasm Innovation of Tropical Special Forest Trees and Ornamental Plants, Ministry of Education, Key Laboratory of Germplasm Resources Biology of Tropical Special Ornamental Plants of Hainan Province, College of Forestry, Hainan University, Haikou, Hainan, China 3 Key Laboratory of Integrated Pest Management on Crops in South China, Ministry of Agriculture, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China 4 Key Laboratory of Integrated Pest Management on Tropical Crops, Ministry of Agriculture China, Environ- ment and Plant Protection Institute, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, Haikou, Hainan, China ABSTRACT Background. Red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Olivier, is one of the most destructive pests harming palm trees. However, genomic resources for R. ferrugineus are still lacking, limiting the ability to discover molecular and genetic means of pest control. Methods. In this study, PacBio Iso-Seq and Illumina RNA-seq were used to generate transcriptome from three developmental stages of R. ferrugineus (pupa, 7th-instar larva, adult) to increase the understanding of the life cycle and molecular characteristics of the pest. Results. Sequencing generated 625,983,256 clean reads, from which 63,801 full-length transcripts were assembled with N50 of 3,547 bp. Expression analyses revealed 8,583 differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Moreover, gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis revealed that these Submitted 5 March 2020 Accepted 29 September 2020 DEGs were mainly related to the peroxisome pathway which associated with metabolic Published 2 November 2020 pathways, material transportation and organ tissue formation. -

Department of Environmental and Forest Biology Annual Report Summer 2016 Academic Year 2016

Department of Environmental and Forest Biology Annual Report Summer 2016 Academic Year 2016 – 2017 Donald J. Leopold Chair, Department of Environmental and Forest Biology SUNY-ESF 1 Forestry Drive Syracuse, NY 13210 Email: [email protected]; ph: (315) 470-6760 August 15, 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . .4 Overview to Annual Report . 4 Building(s) . 6 Teaching . 6 Summary of main courses taught by faculty members . .6 Course teaching load summary by faculty members . 10 Undergraduate student advising loads . 12 Curriculum changes . 12 Undergraduate students enrolled in each EFB major . 12 Listing of awards and recognition . 13 Undergraduate Recruitment Efforts . .13 Student Learning Outcomes Assessment . .14 Research/Scholarship . .14 Summary of publications/presentations . .14 Science Citation Indices . 14 Most Cited Publication of Each EFB Faculty Member . 18 Summary of grant activity . 20 Patents and Patent Applications . 22 Listing of awards and recognition . 22 Outreach and Service . 22 Service to the department, college, and university . 22 Enumeration of outreach activities . 22 Summary of grant panel service . 23 Number of journal manuscripts reviewed by faculty. 23 Summary of journal editorial board service. 23 Listing of awards and recognition . 24 Service Learning . 24 Graduate Students. .26 Number of students by degree objectives . 26 Graduate student national fellowships/awards . 26 Graduate recruitment efforts . 26 Graduate student advising . 28 2 Courses having TA support and enrollment in each . .28 Graduate Program Accomplishments – Miscellaneous. .29 Governance and Administrative Structure . .. .29 Components. .29 Supporting offices, committees, directors, and coordinators . .30 Budget . .32 State budget allocations . .32 Funds Generated by Summer Courses and Grad Tuition Incentive Program . -

Insect Pest List by Host Tree and Reported Country

Insect pest list by host tree and reported country Scientific name Acalolepta cervina Hope, 1831 Teak canker grub|Eng Cerambycidae Coleoptera Hosting tree Genera Species Family Tree species common name Reported Country Tectona grandis Verbenaceae Teak-Jati Thailand Scientific name Amblypelta cocophaga Fruit spotting bug|eng Coconut Coreidae Hemiptera nutfall bug|Eng, Chinche del Hosting tree Genera Species Family Tree species common name Reported Country Agathis macrophylla Araucariaceae Kauri Solomon Islands Eucalyptus deglupta Myrtaceae Kamarere-Bagras Solomon Islands Scientific name Anoplophora glabripennis Motschulsky Asian longhorn beetle (ALB)|eng Cerambycidae Coleoptera Hosting tree Genera Species Family Tree species common name Reported Country Paraserianthes falcataria Leguminosae Sengon-Albizia-Falcata-Molucca albizia- China Moluccac sau-Jeungjing-Sengon-Batai-Mara- Falcata Populus spp. Salicaceae Poplar China Salix spp. Salicaceae Salix spp. China 05 November 2007 Page 1 of 35 Scientific name Aonidiella orientalis Newstead, Oriental scale|eng Diaspididae Homoptera 1894 Hosting tree Genera Species Family Tree species common name Reported Country Lovoa swynnertonii Meliaceae East African walnut Cameroon Azadirachta indica Meliaceae Melia indica-Neem Nigeria Scientific name Apethymus abdominalis Lepeletier, Tenthredinidae Hymenoptera 1823 Hosting tree Genera Species Family Tree species common name Reported Country Other Coniferous Other Coniferous Romania Scientific name Apriona germari Hope 1831 Long-horned beetle|eng Cerambycidae -

LONGHORN BEETLE CHECKLIST - Beds, Cambs and Northants

LONGHORN BEETLE CHECKLIST - Beds, Cambs and Northants BCN status Conservation Designation/ current status Length mm In key? Species English name UK status Habitats Acanthocinus aedilis Timberman Beetle o Nb 12-20 conifers, esp pine n Agapanthia cardui vr herbaceous plants (very recent arrival in UK) n Agapanthia villosoviridescens Golden-bloomed Grey LHB o f 10-22 mainly thistles & hogweed y Alosterna tabacicolor Tobacco-coloured LHB a f 6-8 misc deciduous, esp. oak, hazel y Anaglyptus mysticus Rufous-shouldered LHB o f Nb 6-14 misc trees and shrubs y Anastrangalia (Anoplodera) sanguinolenta r RDB3 9-12 Scots pine stumps n Anoplodera sexguttata Six-spotted LHB r vr RDB3 12-15 old oak and beech? n Anoplophora glabripennis Asian LHB vr introd 20-40 Potential invasive species n Arhopalus ferus (tristis) r r introd 13-25 pines n Arhopalus rusticus Dusky LHB o o introd 10-30 conifers y Aromia moschata Musk Beetle o f Nb 13-34 willows y Asemum striatum Pine-stump Borer o r introd 8-23 dead, fairly fresh pine stumps y Callidium violaceum Violet LHB r r introd 8-16 misc trees n Cerambyx cerdo ext ext introd 23-53 oak n Cerambyx scopolii ext introd 8-20 misc deciduous n Clytus arietus Wasp Beetle a a 6-15 misc., esp dead branches, posts y Dinoptera collaris r RDB1 7-9 rotten wood with other longhorns n Glaphyra (Molorchus) umbellatarum Pear Shortwing Beetle r o Na 5-8 misc trees & shrubs, esp rose stems y Gracilia minuta o r RDB2 2.5-7 woodland & scrub n Grammoptera abdominalis Black Grammoptera r r Na 6-9 broadleaf, mainly oak y Grammoptera ruficornis -

Zootaxa, Catalogue of Family-Group Names in Cerambycidae

Zootaxa 2321: 1–80 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) ZOOTAXA 2321 Catalogue of family-group names in Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) YVES BOUSQUET1, DANIEL J. HEFFERN2, PATRICE BOUCHARD1 & EUGENIO H. NEARNS3 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Central Experimental Farm, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 10531 Goldfield Lane, Houston, TX 77064, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Biology, Museum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Corresponding author: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by Q. Wang: 2 Dec. 2009; published: 22 Dec. 2009 Yves Bousquet, Daniel J. Heffern, Patrice Bouchard & Eugenio H. Nearns CATALOGUE OF FAMILY-GROUP NAMES IN CERAMBYCIDAE (COLEOPTERA) (Zootaxa 2321) 80 pp.; 30 cm. 22 Dec. 2009 ISBN 978-1-86977-449-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-86977-450-9 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2009 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2009 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. -

09.04.2019 Several Notes Were Added

Updated: 09.04.2019 Several notes were added: #393 Viktora & Liu (2018b): Acrocyrtidus jianfeng Viktora & Liu, 2018b and Platycyrtidus yinghuii Viktora & Liu, 2018b are described from Hainan (China). Acrocyrtidus fulvus Gressitt & Rondon, 1970 is recorded from Hainan. Viktora P. & Liu B. 2018b: Notes on Asian Compsocerini Thomson, 1864 (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae, Cerambycinae) with descriptions of four new species and one new record. Folia Heyrovskyana, sries A, 26 (2): 121-142. #394 Viktora & Liu (2018c): Clytus bellus Holzschuh, 1998 (North Vietnam) is excluded from China fauna; it was included after wrong record by Hua et al (2009: 299) for Hainan. Clytus famosus Viktora & Liu, 2018c [=Clytus bellus, sensu Hua et al (2009: 299)] is described from Hainan. Demonax vendibilis Viktora & Liu, 2018c is described from Hainan. Perissus divinus Viktora & Liu, 2018c is described from Guangxi, Liuzhou County. Perissus expletus Viktora & Liu, 2018c is described from Yunnan. Perissus funicatus Viktora & Liu, 2018c is described from Yunnan. Petraphuma huangjianbini Viktora & Liu, 2018c is described from Yunnan. Petraphuma pompa Viktora & Liu, 2018c is described from Hainan. Rhaphuma caraganicola Viktora & Liu, 2018c is described from Xizang (Chayu County). Rhaphuma jianfenglingensis Viktora & Liu, 2018c is described from Hainan. Rhaphuma liyinghuii Viktora & Liu, 2018c is described from Yunnan. Xylotrechus inflexus Viktora & Liu, 2018c is described from Guangxi. Xylotrechus marketae Viktora & Liu, 2018c is described from Yunnan. Xylotrechus zhouchaoi Viktora & Liu, 2018c is described from Yunnan. Hua L.Z., Nara H., Saemulson [Samuelson] G. A. & Langafelter [Lingafelter] S. W. 2009: Iconography of Chinese Longicorn Beetles (1406 Species) in Color. Sun Yat-sen University Press, Guangzhou: 474p. Viktora P. & Liu B. -

Handbook of Zoology

Handbook of Zoology Founded by Willy Kükenthal Editor-in-chief Andreas Schmidt-Rhaesa Arthropoda: Insecta Editors Niels P. Kristensen & Rolf G. Beutel Authenticated | [email protected] Download Date | 5/8/14 6:22 PM Richard A. B. Leschen Rolf G. Beutel (Volume Editors) Coleoptera, Beetles Volume 3: Morphology and Systematics (Phytophaga) Authenticated | [email protected] Download Date | 5/8/14 6:22 PM Scientific Editors Richard A. B. Leschen Landcare Research, New Zealand Arthropod Collection Private Bag 92170 1142 Auckland, New Zealand Rolf G. Beutel Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena Institute of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Biology 07743 Jena, Germany ISBN 978-3-11-027370-0 e-ISBN 978-3-11-027446-2 ISSN 2193-4231 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. Bibliografic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Copyright 2014 by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Compuscript Ltd., Shannon, Ireland Printing and Binding: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Authenticated | [email protected] Download Date | 5/8/14 6:22 PM Cerambycidae Latreille, 1802 77 2.4 Cerambycidae Latreille, Batesian mimic (Elytroleptus Dugés, Cerambyc inae) feeding upon its lycid model (Eisner et al. 1962), 1802 the wounds inflicted by the cerambycids are often non-lethal, and Elytroleptus apparently is not unpal- Petr Svacha and John F. Lawrence atable or distasteful even if much of the lycid prey is consumed (Eisner et al.