American Democracy in the 21St Century: a Retrospective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document Country: Macedonia Lfes ID: Rol727

Date Printed: 11/06/2008 JTS Box Number: lFES 7 Tab Number: 5 Document Title: Macedonia Final Report, May 2000-March 2002 Document Date: 2002 Document Country: Macedonia lFES ID: ROl727 I I I I I I I I I IFES MISSION STATEMENT I I The purpose of IFES is to provide technical assistance in the promotion of democracy worldwide and to serve as a clearinghouse for information about I democratic development and elections. IFES is dedicated to the success of democracy throughout the world, believing that it is the preferred form of gov I ernment. At the same time, IFES firmly believes that each nation requesting assistance must take into consideration its unique social, cultural, and envi I ronmental influences. The Foundation recognizes that democracy is a dynam ic process with no single blueprint. IFES is nonpartisan, multinational, and inter I disciplinary in its approach. I I I I MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK Macedonia FINAL REPORT May 2000- March 2002 USAID COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT No. EE-A-00-97-00034-00 Submitted to the UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT by the INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR ELECTION SYSTEMS I I TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTNE SUMMARY I I. PROGRAMMATIC ACTNITIES ............................................................................................. 1 A. 2000 Pre Election Technical Assessment 1 I. Background ................................................................................. 1 I 2. Objectives ................................................................................... 1 3. Scope of Mission .........................................................................2 -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Electoral Systems Used Around the World

Chapter 4 Electoral Systems Used around the World Siamak F. Shahandashti Newcastle University, UK CONTENTS 4.1 Introduction ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 78 4.2 Some Solutions to Electing a Single Winner :::::::::::::::::::::::: 79 4.3 Some Solutions to Electing Multiple Winners ::::::::::::::::::::::: 82 4.4 Blending Systems Together :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 87 4.5 Other Solutions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 88 4.6 Which Systems Are Good? ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1 A Theorist’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.1 Majority Rules ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.2 Bad News Begins :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 91 4.6.1.3 Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem ::::::::::::::::: 93 4.6.1.4 Gibbard–Satterthwaite Impossibility Theorem ::: 94 4.6.1.5 Systems with Respect to Criteria :::::::::::::::: 95 4.6.2 A Practitioner’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 97 Acknowledgment ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 101 77 78 Real-World Electronic Voting: Design, Analysis and Deployment 4.1 Introduction An electoral system, or simply a voting method, defines the rules by which the choices or preferences of voters are collected, tallied, aggregated and collectively interpreted to obtain the results of an election [249, 489]. There are many electoral systems. A voter may be allowed to vote for one or multiple candidates, one or multiple predefined lists of candidates, or state their pref- erence among candidates or predefined lists of candidates. Accordingly, tallying may involve a simple count of the number of votes for each candidate or list, or a relatively more complex procedure of multiple rounds of counting and transferring ballots be- tween candidates or lists. Eventually, the outcome of the tallying and aggregation procedures is interpreted to determine which candidate wins which seat. Designing end-to-end verifiable e-voting schemes is challenging. -

Electoral Reform Three Case Studies

Electoral reform Three Case Studies • Japan • New Zealand • Italy MMM vs. MMP • MMM vs. MMP… what’s the difference? • In both, seats are allocated at the district and national levels • MMP is a hybrid system – District-level winners – National PR is compensatory • MMM is a parallel voting system – List seats allocated proportionally… – …But not linked to district-level winners • What are plusses and minuses? Why do political scientists like MMP better? Electoral reform: Japan (1996) • BEFORE: SNTV – What kinds of problems did SNTV bring? • AFTER: MMM • WHY: LDP wanted reform. Electoral reform: Japan • In 1970, PM Satō asked a party committee to propose an electoral system based on single-seat districts to “produce party-centered, policy-centered campaigns.” Effect of electoral reform: Indices Year D (LSq) N(v) N(s) S 6.20 3.82 3.08 12.28 3.66 2.60 Period averages in red (overall in post-reform period through 2009) 6 2009 Election Results Electoral reform: New Zealand (1996) • BEFORE: FPTP • AFTER: MMP • WHY: It’s complicated! New Zealand: Problems with the old system 9 An electoral system working “too well” New Zealand is classic case of an electoral system producing too much majoritarianism New Zealand Electoral Statistics, 1978-1993 Party 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 Labour Vote % 40.4 39.0 43.0 48.0 35.1 34.7 Seat % 43.5 46.7 60.0 58.8 29.9 45.5 National Vote % 39.8 38.8 35.9 44.0 47.8 35.0 Seat % 55.4 51.1 37.9 41.2 69.1 50.5 Social Credit Vote % 16.1 20.7 7.6 - - - Seat % 1.1 2.2 2.1 - - - NZ Party Vote % - - 12.3 0.3 - - Seat % - - 0.0 0.0 - - *Alliance Vote % - - - - 14.3 18.2 Seat % - - - - 1.0 2.0 NZ First Vote % - - - - - 8.4 Seat % - - - - - 0.0 *The Alliance consists of several minor third parties, including Green, New Labour, Democrat and Mana Motuhake. -

Theoretical Comparisons of Electoral Systems Roger B

European Economic Review 43 (1999) 671—697 Joseph Schumpeter Lecture Theoretical comparisons of electoral systems Roger B. Myerson Kellog Graduate School of Management, Northwestern University, 2001 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208-2009, USA Abstract Elements of an economic theory of political institutions are introduced. A variety of electoral systems are reviewed. Cox’s threshold is shown to measure incentives for diversity and specialization of candidates’ positions, when the number of serious candi- dates is given. Duverger’s law and its generalizations are discussed, to predict the number of serious candidates. Duverger’s law is interpreted as a statement about electoral barriers to entry, and this idea is linked to the question of the effectiveness of democratic competition as a deterrent to political corruption. The impact of post-electoral bargain- ing on party structure in presidential and parliamentary systems is discussed. ( 1999 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. JEL classification: D72 Keywords: Electoral systems; Constitution; Election game; Incentives 1. Invitation to political economics To honor Joseph Schumpeter, I should try to begin as he might, from a long view of the history of economic theory, observing that the scope of economics has changed. With an initial goal of explaining the production and allocation of material goods, economic theorists developed analytical tools to predict how changes in market structure may affect rational behavior of producers and consumers. As the principles of rational choice were first developed in this context of price-theoretic decision-making, it seemed sensible to separate the study of markets from the study of other great institutions of society, because 0014-2921/99/$ — see front matter ( 1999 Elsevier Science B.V. -

The Many Faces of Strategic Voting

Revised Pages The Many Faces of Strategic Voting Strategic voting is classically defined as voting for one’s second pre- ferred option to prevent one’s least preferred option from winning when one’s first preference has no chance. Voters want their votes to be effective, and casting a ballot that will have no influence on an election is undesirable. Thus, some voters cast strategic ballots when they decide that doing so is useful. This edited volume includes case studies of strategic voting behavior in Israel, Germany, Japan, Belgium, Spain, Switzerland, Canada, and the United Kingdom, providing a conceptual framework for understanding strategic voting behavior in all types of electoral systems. The classic definition explicitly considers strategic voting in a single race with at least three candidates and a single winner. This situation is more com- mon in electoral systems that have single- member districts that employ plurality or majoritarian electoral rules and have multiparty systems. Indeed, much of the literature on strategic voting to date has considered elections in Canada and the United Kingdom. This book contributes to a more general understanding of strategic voting behavior by tak- ing into account a wide variety of institutional contexts, such as single transferable vote rules, proportional representation, two- round elec- tions, and mixed electoral systems. Laura B. Stephenson is Professor of Political Science at the University of Western Ontario. John Aldrich is Pfizer- Pratt University Professor of Political Science at Duke University. André Blais is Professor of Political Science at the Université de Montréal. Revised Pages Revised Pages THE MANY FACES OF STRATEGIC VOTING Tactical Behavior in Electoral Systems Around the World Edited by Laura B. -

LWV”) Has Been a Leader in the Fight for Fair and Transparent Elections and Good Governance

How Alaska Ballot Measure 2 advances the goals of the League of Women Voters Shea Siegert Yes on 2 Campaign Manager July 10, 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Since its founding in 1920, the League of Women Voters (“LWV”) has been a leader in the fight for fair and transparent elections and good governance. As part of that effort, its chapters have taken positions on legislation and ballot initiatives across the country on a range of reforms. In June of 2020, LWV held a vote of concurrence on a position regarding “Voter Representation and Electoral Systems.” This action established eight criteria for assessing whether a proposed electoral reform should be endorsed by local LWV chapters. Those criteria are: Whether for single or multiple winner contests, the League supports electoral methods that: Encourage voter participation and voter engagement Encourage those with minority opinions to participate, including under-represented communities Are verifiable and auditable Promote access to voting Maximize effective votes/minimize wasted votes Promote sincere voting over strategic voting Implement alternatives to plurality voting Are compatible with acceptable ballot-casting methods, including vote-by-mail The 2020 vote of concurrence was taken by 1,400 delegates from LWV Chapters from across the country and was approved by 93% of delegates, far exceeding the two-thirds threshold required to establish a position of concurrence. This document seeks to demonstrate that Alaska Ballot Measure 2 is fully aligned with the eight criteria established in June. We reviewed 30 studies, statements and positions from LWV chapters along with supporting academic studies and research from organizations like Represent Women, Representation2020, Fairvote, and others. -

“No One Whose Opinion Has Weight, Will Contend That Some Clumsy

“No one whose opinion has weight, will contend that some clumsy machine of primitive times, which served its day and generation, is for ever to be regarded with superstitious reverence” Sir Sandford Fleming on the need to change Canada’s first-past-the-post voting system, taken from On The Rectification of Parliament address delivered to the Canadian Institute, Toronto, 1892 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Nick Loenen is a sessional lecturer at the University of British Columbia teaching British Columbia Governance and Politics, a former Richmond City Councillor (1983-87), and former Member of the British Columbia Legislature (1986-91). He has written extensively on voting system reform. His book Citizenship and Democracy, a case for proportional representation, was published by Dundurn Press, Toronto in 1997. In 1998 he founded Fair Voting BC, a multi-partisan citizens group which since its inception lobbied for a referendum on voting system reform and helped shape the Citizens Assembly process in BC. RECOMMENDATION Replace Ontario’s current voting system with the Single Transferable Vote (STV) to elect candidates by preferential ballot in multi-seat ridings The Single Transferable Vote is uniquely suited to meet Ontario’s geography, diverse and polarized political culture, and British form of government. The submission starts by listing Five Goals, which it is submitted accurately capture what most Ontario citizens expect from their voting system. The Single Transferable Vote is designed to best meet those five goals. The Single Transferable Vote is not full proportional representation, it is an in- between system. Most proportional representation systems decrease local representation and increase the power of political parties. -

Gerrymandering and Fair Districting in Parallel Voting Systems Arxiv

Gerrymandering and fair districting in parallel voting systems Igor Mandric1, Igor Roşca2, and Radu Buzatu3 1Department of Computer Science, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chişinˇau,Moldova 3Department of Mathematics, Moldova State University, Chişinˇau, Moldova Abstract Switching from one electoral system to another one is frequently criticized by the opposition and is viewed as a means for the ruling party to stay in power. In particular, when the new electoral system is a parallel voting (or a single-member district) system, the ruling party is usually suspected of a bi- ased way of partitioning the state into electoral districts such that based on a priori knowledge it has more chances to win in a maximum possible number of districts. In this paper, we propose a new methodology for deciding whether a particular party benefits from a given districting map under a parallel voting system. As a part of our methodology, we formulate and solve several gerry- mandering problems. We showcased the application of our approach to the Moldovan parliamentary elections of 2019. Our results suggest that contrary to the arguments of previous studies, there is no clear evidence to consider that the districting map used in those elections was unfair. 1 Introduction arXiv:2002.06849v1 [physics.soc-ph] 17 Feb 2020 Political (re-)districting represents the task of partitioning a geographic area (e.g., a state or an administrative unit) into a given number of electoral districts subject to a predefined set of requirements [1]. Frequently, the requirements are formulated with respect to demographic and/or geographic peculiarities of the area [2]. -

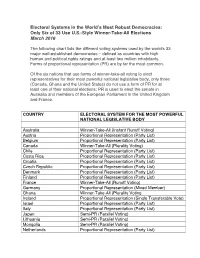

Electoral Systems in the World's Most Robust Democracies

Electoral Systems in the World’s Most Robust Democracies: Only Six of 33 Use U.S.-Style Winner-Take-All Elections March 2016 The following chart lists the different voting systems used by the world's 33 major well-established democracies – defined as countries with high human and political rights ratings and at least two million inhabitants. Forms of proportional representation (PR) are by far the most common. Of the six nations that use forms of winner-take-all voting to elect representatives for their most powerful national legislative body, only three (Canada, Ghana and the United States) do not use a form of PR for at least one of their national elections; PR is used to elect the senate in Australia and members of the European Parliament in the United Kingdom and France. COUNTRY ELECTORAL SYSTEM FOR THE MOST POWERFUL NATIONAL LEGISLATIVE BODY Australia Winner-Take-All (Instant Runoff Voting) Austria Proportional Representation (Party List) Belgium Proportional Representation (Party List) Canada Winner-Take-All (Plurality Voting) Chile Proportional Representation (Party List) Costa Rica Proportional Representation (Party List) Croatia Proportional Representation (Party List) Czech Republic Proportional Representation (Party List) Denmark Proportional Representation (Party List) Finland Proportional Representation (Party List) France Winner-Take-All (Runoff Voting) Germany Proportional Representation (Mixed Member) Ghana Winner-Take-All (Plurality Voting Ireland Proportional Representation (Single Transferable Vote) Israel Proportional -

Revised Comparative Table on Proportional Electoral

Strasbourg, 30 April 2015 CDL-PI(2015)006 Study No. 764/2014 Or. Engl./fr. EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) REVISED COMPARATIVE TABLE1 ON PROPORTIONAL ELECTORAL SYSTEMS: THE ALLOCATION OF SEATS INSIDE THE LISTS (OPEN/CLOSED LISTS) 1 The legal provisions contained in this table refer to lower chambers, unless otherwise indicated. This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera pas distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. www.venice.coe.int CDL-PI(2015)006 - 2 - Proportional systems, Proportional systems: Electoral systems, Proportional systems, methods of allocation of Country Legal basis System of representation closed or open party main relevant provision(s) methods of allocation of seats seats list system? inside the lists Constitution Proportional system: Constitution Largest remainder Closed Party List No preference Article 64 All the 140 members of the Article 64 (amended by Law no. D’Hondt, then Sainte-Laguë system Not indicated in the law but Parliament are elected through 9904, dated 21.04.2008) formulas No preference implicitly clear that there is Electoral Code a proportional representation 1. The Assembly consists of 140 no preference. (approved by Law system within constituencies deputies, elected by a proportional See the separate document for no. 10 019, dated 29 corresponding to the 12 system with multi-member electoral Articles 162-163. December 2008, administrative regions. zones. and amended by The threshold to win 2. A multi-member electoral zone According to the stipulations in Law no. 74/2012, parliamentary representation is coincides with the administrative Articles 162 and 163 of the Electoral dated 19 July 2012) 3 percent for political parties division of one of the levels of Code, the number of seats is Articles 162 & 163 and 5 per cent for pre-election administrative-territorial calculated for each of the coalitions coalitions. -

Comparative Table on Proportional Electoral Systems

Strasbourg, 28 November 2014 CDL(2014)058 Study No. 764/2014 Or. bil. EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) COMPARATIVE TABLE ON PROPORTIONAL ELECTORAL SYSTEMS: THE ALLOCATION OF SEATS INSIDE THE LISTS (OPEN/CLOSED LISTS) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL(2014)058 - 2 - Proportional systems, Proportional systems: Electoral systems, Proportional systems, methods of allocation of Country Legal basis System of representation closed or open party main relevant provision(s) methods of allocation of seats seats list system? inside the lists Constitution Proportional system: Constitution Largest remainder Closed Party List No preference Article 64 All the 140 members of the Article 64 (amended by Law no. d'Hondt, then Sainte-Laguë system Not indicated in the law but Parliament are elected through 9904, dated 21.04.2008) formulas No preference implicitly clear that there is Electoral Code a proportional representation 1. The Assembly consists of 140 no preference. (approved by Law system within constituencies deputies, elected by a proportional See the separate document for no. 10 019, dated 29 corresponding to the 12 system with multi-member electoral Articles 162-163. December 2008, administrative regions. zones. and amended by The threshold to win 2. A multi-member electoral zone According to the stipulations in Law no. 74/2012, parliamentary representation is coincides with the administrative Articles 162 and 163 of the Electoral dated 19 July 2012) 3 percent for political parties division of one of the levels of Code, the number of seats is Articles 162 & 163 and 5 per cent for pre-election administrative-territorial calculated for each of the coalitions coalitions.