Towers of Strength in Turbulent Times?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document Country: Macedonia Lfes ID: Rol727

Date Printed: 11/06/2008 JTS Box Number: lFES 7 Tab Number: 5 Document Title: Macedonia Final Report, May 2000-March 2002 Document Date: 2002 Document Country: Macedonia lFES ID: ROl727 I I I I I I I I I IFES MISSION STATEMENT I I The purpose of IFES is to provide technical assistance in the promotion of democracy worldwide and to serve as a clearinghouse for information about I democratic development and elections. IFES is dedicated to the success of democracy throughout the world, believing that it is the preferred form of gov I ernment. At the same time, IFES firmly believes that each nation requesting assistance must take into consideration its unique social, cultural, and envi I ronmental influences. The Foundation recognizes that democracy is a dynam ic process with no single blueprint. IFES is nonpartisan, multinational, and inter I disciplinary in its approach. I I I I MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK Macedonia FINAL REPORT May 2000- March 2002 USAID COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT No. EE-A-00-97-00034-00 Submitted to the UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT by the INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR ELECTION SYSTEMS I I TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTNE SUMMARY I I. PROGRAMMATIC ACTNITIES ............................................................................................. 1 A. 2000 Pre Election Technical Assessment 1 I. Background ................................................................................. 1 I 2. Objectives ................................................................................... 1 3. Scope of Mission .........................................................................2 -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Electoral Reform Three Case Studies

Electoral reform Three Case Studies • Japan • New Zealand • Italy MMM vs. MMP • MMM vs. MMP… what’s the difference? • In both, seats are allocated at the district and national levels • MMP is a hybrid system – District-level winners – National PR is compensatory • MMM is a parallel voting system – List seats allocated proportionally… – …But not linked to district-level winners • What are plusses and minuses? Why do political scientists like MMP better? Electoral reform: Japan (1996) • BEFORE: SNTV – What kinds of problems did SNTV bring? • AFTER: MMM • WHY: LDP wanted reform. Electoral reform: Japan • In 1970, PM Satō asked a party committee to propose an electoral system based on single-seat districts to “produce party-centered, policy-centered campaigns.” Effect of electoral reform: Indices Year D (LSq) N(v) N(s) S 6.20 3.82 3.08 12.28 3.66 2.60 Period averages in red (overall in post-reform period through 2009) 6 2009 Election Results Electoral reform: New Zealand (1996) • BEFORE: FPTP • AFTER: MMP • WHY: It’s complicated! New Zealand: Problems with the old system 9 An electoral system working “too well” New Zealand is classic case of an electoral system producing too much majoritarianism New Zealand Electoral Statistics, 1978-1993 Party 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 Labour Vote % 40.4 39.0 43.0 48.0 35.1 34.7 Seat % 43.5 46.7 60.0 58.8 29.9 45.5 National Vote % 39.8 38.8 35.9 44.0 47.8 35.0 Seat % 55.4 51.1 37.9 41.2 69.1 50.5 Social Credit Vote % 16.1 20.7 7.6 - - - Seat % 1.1 2.2 2.1 - - - NZ Party Vote % - - 12.3 0.3 - - Seat % - - 0.0 0.0 - - *Alliance Vote % - - - - 14.3 18.2 Seat % - - - - 1.0 2.0 NZ First Vote % - - - - - 8.4 Seat % - - - - - 0.0 *The Alliance consists of several minor third parties, including Green, New Labour, Democrat and Mana Motuhake. -

Gerrymandering and Fair Districting in Parallel Voting Systems Arxiv

Gerrymandering and fair districting in parallel voting systems Igor Mandric1, Igor Roşca2, and Radu Buzatu3 1Department of Computer Science, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chişinˇau,Moldova 3Department of Mathematics, Moldova State University, Chişinˇau, Moldova Abstract Switching from one electoral system to another one is frequently criticized by the opposition and is viewed as a means for the ruling party to stay in power. In particular, when the new electoral system is a parallel voting (or a single-member district) system, the ruling party is usually suspected of a bi- ased way of partitioning the state into electoral districts such that based on a priori knowledge it has more chances to win in a maximum possible number of districts. In this paper, we propose a new methodology for deciding whether a particular party benefits from a given districting map under a parallel voting system. As a part of our methodology, we formulate and solve several gerry- mandering problems. We showcased the application of our approach to the Moldovan parliamentary elections of 2019. Our results suggest that contrary to the arguments of previous studies, there is no clear evidence to consider that the districting map used in those elections was unfair. 1 Introduction arXiv:2002.06849v1 [physics.soc-ph] 17 Feb 2020 Political (re-)districting represents the task of partitioning a geographic area (e.g., a state or an administrative unit) into a given number of electoral districts subject to a predefined set of requirements [1]. Frequently, the requirements are formulated with respect to demographic and/or geographic peculiarities of the area [2]. -

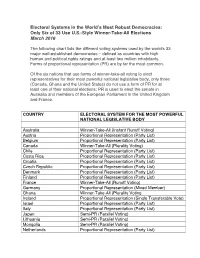

Electoral Systems in the World's Most Robust Democracies

Electoral Systems in the World’s Most Robust Democracies: Only Six of 33 Use U.S.-Style Winner-Take-All Elections March 2016 The following chart lists the different voting systems used by the world's 33 major well-established democracies – defined as countries with high human and political rights ratings and at least two million inhabitants. Forms of proportional representation (PR) are by far the most common. Of the six nations that use forms of winner-take-all voting to elect representatives for their most powerful national legislative body, only three (Canada, Ghana and the United States) do not use a form of PR for at least one of their national elections; PR is used to elect the senate in Australia and members of the European Parliament in the United Kingdom and France. COUNTRY ELECTORAL SYSTEM FOR THE MOST POWERFUL NATIONAL LEGISLATIVE BODY Australia Winner-Take-All (Instant Runoff Voting) Austria Proportional Representation (Party List) Belgium Proportional Representation (Party List) Canada Winner-Take-All (Plurality Voting) Chile Proportional Representation (Party List) Costa Rica Proportional Representation (Party List) Croatia Proportional Representation (Party List) Czech Republic Proportional Representation (Party List) Denmark Proportional Representation (Party List) Finland Proportional Representation (Party List) France Winner-Take-All (Runoff Voting) Germany Proportional Representation (Mixed Member) Ghana Winner-Take-All (Plurality Voting Ireland Proportional Representation (Single Transferable Vote) Israel Proportional -

Revised Comparative Table on Proportional Electoral

Strasbourg, 30 April 2015 CDL-PI(2015)006 Study No. 764/2014 Or. Engl./fr. EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) REVISED COMPARATIVE TABLE1 ON PROPORTIONAL ELECTORAL SYSTEMS: THE ALLOCATION OF SEATS INSIDE THE LISTS (OPEN/CLOSED LISTS) 1 The legal provisions contained in this table refer to lower chambers, unless otherwise indicated. This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera pas distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. www.venice.coe.int CDL-PI(2015)006 - 2 - Proportional systems, Proportional systems: Electoral systems, Proportional systems, methods of allocation of Country Legal basis System of representation closed or open party main relevant provision(s) methods of allocation of seats seats list system? inside the lists Constitution Proportional system: Constitution Largest remainder Closed Party List No preference Article 64 All the 140 members of the Article 64 (amended by Law no. D’Hondt, then Sainte-Laguë system Not indicated in the law but Parliament are elected through 9904, dated 21.04.2008) formulas No preference implicitly clear that there is Electoral Code a proportional representation 1. The Assembly consists of 140 no preference. (approved by Law system within constituencies deputies, elected by a proportional See the separate document for no. 10 019, dated 29 corresponding to the 12 system with multi-member electoral Articles 162-163. December 2008, administrative regions. zones. and amended by The threshold to win 2. A multi-member electoral zone According to the stipulations in Law no. 74/2012, parliamentary representation is coincides with the administrative Articles 162 and 163 of the Electoral dated 19 July 2012) 3 percent for political parties division of one of the levels of Code, the number of seats is Articles 162 & 163 and 5 per cent for pre-election administrative-territorial calculated for each of the coalitions coalitions. -

Comparative Table on Proportional Electoral Systems

Strasbourg, 28 November 2014 CDL(2014)058 Study No. 764/2014 Or. bil. EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) COMPARATIVE TABLE ON PROPORTIONAL ELECTORAL SYSTEMS: THE ALLOCATION OF SEATS INSIDE THE LISTS (OPEN/CLOSED LISTS) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL(2014)058 - 2 - Proportional systems, Proportional systems: Electoral systems, Proportional systems, methods of allocation of Country Legal basis System of representation closed or open party main relevant provision(s) methods of allocation of seats seats list system? inside the lists Constitution Proportional system: Constitution Largest remainder Closed Party List No preference Article 64 All the 140 members of the Article 64 (amended by Law no. d'Hondt, then Sainte-Laguë system Not indicated in the law but Parliament are elected through 9904, dated 21.04.2008) formulas No preference implicitly clear that there is Electoral Code a proportional representation 1. The Assembly consists of 140 no preference. (approved by Law system within constituencies deputies, elected by a proportional See the separate document for no. 10 019, dated 29 corresponding to the 12 system with multi-member electoral Articles 162-163. December 2008, administrative regions. zones. and amended by The threshold to win 2. A multi-member electoral zone According to the stipulations in Law no. 74/2012, parliamentary representation is coincides with the administrative Articles 162 and 163 of the Electoral dated 19 July 2012) 3 percent for political parties division of one of the levels of Code, the number of seats is Articles 162 & 163 and 5 per cent for pre-election administrative-territorial calculated for each of the coalitions coalitions. -

Venezuela: 2020 Parliamentary Election

BRIEFING PAPER CBP 9113, 18 January 2021 Venezuela: 2020 By Nigel Walker parliamentary election Contents: 1. Background 2. 2020 Parliamentary election www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Venezuela: 2020 parliamentary election Contents Summary 3 1. Background 4 2. 2020 Parliamentary election 5 2.1 Political parties 5 2.2 Election campaign 7 2.3 Election results 8 2.4 International reaction 9 2.5 Looking ahead 10 Cover page image copyright Flag of Venezuela (1) by Beatrice Murch from Buenos Aires, Argentina – Wikimedia Commons page. / image cropped. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) 3 Commons Library Briefing, 18 January 2021 Summary Venezuela held a parliamentary election on Sunday 6 December 2020. Ahead of the election campaign beginning, several opposition parties announced they would not participate, declaring the election to be fraudulent and illegitimate. President Maduro’s ruling socialist party – the PSUV – secured a landslide victory, taking 253 of the 277 available seats in the National Assembly. This victory sees Maduro taking control of all branches of state in Venezuela. Many in the international community have refused to recognise the election result. Meanwhile, opposition leader Juan Guaidó has vowed to continue as interim President and Deputies elected to the 2015 parliament, which he presided over, have voted to extend their mandate. Thus, Venezuela has two contested Presidents and National Assemblies, reflecting the enduring political struggle between Maduro and Guaidó. Constitutionally, such a situation cannot continue indefinitely. 4 Venezuela: 2020 parliamentary election 1. Background Legislative elections in Venezuela take place every five years. -

Mathematics: the Last Truth of Democracy?

Mathematics: The Last Truth of Democracy? J.Popkin !"#$%&'$: )*$ , %*-%*#*.$ $ℎ* )0#$ 12 '&.303&$*# 0. &.4 506*. *)*'$01. &.3 7 "* $ℎ* *)*'$1%&$* 8ℎ*%* 7 = . &.3 , = :. <=%$ℎ*%:1%* 3*20.* $ℎ* -%*2*%*.$0&) "0.&%4 1-*%&$1% c? ≻A cB 21% c?, cB ∈ , $1 EF %*-%*#*.$ $ℎ* 0 61$*% -%*2*%%0.5 '&.303&$* c ? $1 c B. G2 $ℎ* 16*%&)) '1.'*#=# 0# '&.303&$* c? 16*% cB $ℎ*. 8* 3*.1$* $ℎ0# c? ≻H cB. I*$ JA: , → LA "* $ℎ* 'ℎ10'* 2=.'$01. 12 $ℎ* EF 0 61$*% 8ℎ*%* LA %*-%*#*.$# & %&.M0.5 12 *)*:*.$# '?, … , 'O &.3 20.&))4 )*$ <: J , → LH "* $ℎ* 2=.'$01. 12 &. *)*'$1%&) #4#$*: 8ℎ*%* J , = L?, … , LP &.3 LH %*-%*#*.$# $ℎ* 1=$-=$ %&.M0.5 12 '&.303&$*# §1. Introduction Whilst the applications of mathematics to topics like physics and economics are well explored, its applications to politics are often heavily overlooked. After all, the very foundations of democracy in the modern world and built around the idea of numbers; it is not as simple as adding up the number of votes and there are various functions, indices and axioms used in order to construct a working electoral system. Primarily there exists two different ways of classifying electoral systems, the first being preferential vs non- preferential. A preferential system is defined as ranking the candidates from 1 to m; these rankings can be weighted. Conversely a non-preferential system simply gives the voter as many votes as there are for candidates to be elected which is often far less centred around mathematical systems since the only preference relation exists between their choice and those they don’t choose. -

Electoral Systems and Political Parties by Jack Bielasiak Indiana University Bloomington

APCG U1 Electoral Systems and Political Parties by Jack Bielasiak Indiana University Bloomington Structural Causes and Partisan Effects Elections have become synonymous with democracy. In all corners of the world, especially since the collapse of communism, politicians have sought to design electoral systems that provide at least some choice to their citizenry. But the process of electoral engineering is a complex one, and the choice of particular rules to govern elections has a profound effect on the extent and type of political competition. A widely accepted proposition in political science, one of the few to claim the status of scientific validity, is Duverger's law. The law concerns the relationship between electoral and party systems: plurality, winner-take- all election rules produce a two-party competitive system, while other electoral regulations, especially proportional representation (PR), tend to form multiparty systems defined by competition among several contending political organizations. The linkage is ascribed to two factors: the mechanical effect and the strategic effect of election rules. The mechanical effect is simply the result of the calculation rules that convert votes into legislative seats. In simple majoritarian systems (i.e., plurality), only those candidates who finish at the top are declared winners and are awarded with parliamentary representation, while losing contenders are left out of the legislature. The electoral regulation of PR systems, on the other hand, rewards as winners many more political contestants, providing legislative seats on the basis of each party's vote share. (See the table below to compare the structures of different nations' electoral systems.) This mechanical effect of translating votes into seats is reinforced by the strategic effect, which concerns the responses of politicians and voters to the rules of the game. -

American Democracy in the 21St Century: a Retrospective

AMERICAN DEMOCRACY IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A RETROSPECTIVE BY DAVID O’BRIEN AND PAM KELLER* [Prepared transcript of remarks to the 2220 Idaho School of Law symposium. Citations and annotations have been added as footnotes.] Thank you very much for the kind introduction. We truly appreciate the invitation to join you in Boise and speak at this conference, not only as an excuse to visit the West Coast and see your lovely beaches but also because it gives us an opportunity to discuss one the most pivotal but (in our opinion) underappreciated subjects of the past two hundred years: the gradual revolution within American democracy that occurred throughout the twenty-first century. We realize that “revolution” may strike some as an extreme claim, particularly since, as we’ll see, so few of the individual reforms were new ideas by the time of their adoption.1 Novelty aside, we think “revolution” is the right word to use. The sheer scope of the changes to America’s electoral processes and institutions has created what is now a profoundly different—and better—democracy than what the nation had in the dramatic and tumultuous early years of that century. It’s important that we understand this “revolution” was not a singular process. It was the product of many disparate efforts and reforms all arising from the ferment of the same dysfunctional system. Each individual change that contributed to the revolution has a unique story, with its own set of characters and motivations. We can only touch on some of the more prominent examples here, but we encourage the audience to read or download further on the various examples we discuss in more detail.2 Nevertheless, there are three broad similarities that each of our examples share. -

Angola: Chronicle of an Unfulfilled Promise a Hundred Days After the Elections

INTERNATIONAL POLICY ANALYSIS Angola: Chronicle of an unfulfilled promise A hundred days after the elections SylVia Croese January 2013 n After ten years of peace with much economic growth but little social development, the 2012 elections have resulted in a contested victory for the long-term incumbent MPLA. While observers such as the African Union (AU) and the Southern African De- velopment Community (SADC) considered the elections to be free, fair and transpar- ent, the European Union and the United States took note of the electoral complaints by the opposition and civil society. n Despite a booming economy and rising GDP per capita levels, Angola is still placed in the low human development category, ranking 148 out of 187 countries in 2011 and classified as one of the most unequal societies in the world. This inequality is not only economic, but also geographic, with economic growth mostly concentrated in Luanda. n The dissatisfaction with skyrocketing prices in the housing market illustrates exem- plarily the growing disconnect between the Angolan government and the people. It represents the feeling amongst many Angolans that it is not poverty that is being combatted, but the poor themselves for whom there is little place in the post-war narrative of reconstruction, development and modernization. n In the face of growing civic discontent, a reinvigorated opposition and administra- tive and economic challenges for successful public policy implementation, this paper argues that the coming years will be crucial for the MPLA to deliver on its promises. SylVia Croese | ANGola: CHronicle OF an UNFULFilleD ProMise Content Introduction . 2 From war to peace: the 1992, 2008 and 2012 elections .