Ch. 7 MOSFET Technology Scaling, Leakage Current, and Other Topics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imperial College London Department of Physics Graphene Field Effect

Imperial College London Department of Physics Graphene Field Effect Transistors arXiv:2010.10382v2 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 20 Jul 2021 By Mohamed Warda and Khodr Badih 20 July 2021 Abstract The past decade has seen rapid growth in the research area of graphene and its application to novel electronics. With Moore's law beginning to plateau, the need for post-silicon technology in industry is becoming more apparent. Moreover, exist- ing technologies are insufficient for implementing terahertz detectors and receivers, which are required for a number of applications including medical imaging and secu- rity scanning. Graphene is considered to be a key potential candidate for replacing silicon in existing CMOS technology as well as realizing field effect transistors for terahertz detection, due to its remarkable electronic properties, with observed elec- tronic mobilities reaching up to 2 × 105 cm2 V−1 s−1 in suspended graphene sam- ples. This report reviews the physics and electronic properties of graphene in the context of graphene transistor implementations. Common techniques used to syn- thesize graphene, such as mechanical exfoliation, chemical vapor deposition, and epitaxial growth are reviewed and compared. One of the challenges associated with realizing graphene transistors is that graphene is semimetallic, with a zero bandgap, which is troublesome in the context of digital electronics applications. Thus, the report also reviews different ways of opening a bandgap in graphene by using bi- layer graphene and graphene nanoribbons. The basic operation of a conventional field effect transistor is explained and key figures of merit used in the literature are extracted. Finally, a review of some examples of state-of-the-art graphene field effect transistors is presented, with particular focus on monolayer graphene, bilayer graphene, and graphene nanoribbons. -

Resume of Zeng Yuping 20180109 for Publishing on Website

Curriculum Vitae Name Yuping Zeng Degree PhD DOB 12/02/1979 Visa Permanent Gender Female E-mail [email protected] Status Resident (U.S.) Mailing Address: Current Affiliation 139 The Green, Evans Hall 140 Assistant Professor Department of ECE Department of ECE University of Delaware University of Delaware Newark, DE 19716 Cell Phone: 510-610-2894 Office Phone: 302-831-3847 Projects Involved and Achievements Ø 34 peer-reviewed journal papers and 16 papers at international conferences; Ø Postdoctoral Research (2011-2016) in UC Berkeley Design and fabrication of InAs/AlSb/GaSb Tunneling Field Effect Transistors; High speed InAs Metal Oxide Semiconductor Field Effect transistors on Silicon (MOSFETs); InAs-on-Si fin field effect transistors (FinFETs) Ø PhD Research (2004-2011) in Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Design and fabrication of high-speed InP/GaAsSb Double-Heterojunction Bipolar Transistors (DHBTs) with record fT and fMAX cut-off frequencies Ø PhD Research (2003-2004) in Simon Fraser University High-speed photodetector; High Electron Mobility Transistors (HEMTs) Ø Second Master Research (2001-2003) in National University of Singapore Raman study of laser annealed silicon and photoluminecence from nano-scaled silicon Ø First Master Research (1998-2001) in Jilin University Fabrication of development of Superluminescent Light Emitting Diode (SLED): InGaAsP/InP and GaAlAs/GaAs Ø Bachelor Research (1994-1998) in Jilin University Mode Analysis of VCSEL with Fiber Gratings as its Distributed Bragg Reflector (DBR) 1 Education Swiss Federal -

The Reliability of the Silicon Nitride Dielectric in Capacitive MEMS

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Materials Science and Engineering THE RELIABILITY OF THE SILICON NITRIDE DIELECTRIC IN CAPACITIVE MEMS SWITCHES A Thesis in Materials Science and Engineering by Abuzer Dogan © 2005 Abuzer Dogan Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2005 I grant The Pennsylvania State University the nonexclusive right to use this work for the University's own purposes and to make single copies of the work available to the public on a not-for-profit basis if copies are not otherwise available. Abuzer Dogan We approve the thesis of Abuzer Dogan. Date of Signature Susan Trolier-McKinstry Professor of Ceramic Science and Engineering Thesis Advisor Michael Lanagan Associate Professor of Engineering Science and Mechanics and Materials Science and Engineering Mark Horn Associate Professor of Engineering Science and Mechanics James P. Runt Professor of Polymer Science Associate Head for Graduate Studies iii ABSTRACT Silicon nitride thin film dielectrics can be used in capacitive radio frequency micro-electromechanical systems switches since they provide a low insertion loss, good isolation, and low return loss. The lifetime of these switches is believed to be adversely affected by charge trapping in the silicon nitride. These charges cause the metal bridge to be partially or fully pulled down, degrading the on-off ratio of the switch. Little information is available in the literature providing a fundamental solution to this problem. Consequently, the goals of this research were to characterize SixNy–based MIM (Metal-Insulator-Metal) capacitors and capacitive MEMS switches to measure the current-voltage response. -

The Economic Impact of Moore's Law: Evidence from When It Faltered

The Economic Impact of Moore’s Law: Evidence from when it faltered Neil Thompson Sloan School of Management, MIT1 Abstract “Computing performance doubles every couple of years” is the popular re- phrasing of Moore’s Law, which describes the 500,000-fold increase in the number of transistors on modern computer chips. But what impact has this 50- year expansion of the technological frontier of computing had on the productivity of firms? This paper focuses on the surprise change in chip design in the mid-2000s, when Moore’s Law faltered. No longer could it provide ever-faster processors, but instead it provided multicore ones with stagnant speeds. Using the asymmetric impacts from the changeover to multicore, this paper shows that firms that were ill-suited to this change because of their software usage were much less advantaged by later improvements from Moore’s Law. Each standard deviation in this mismatch between firm software and multicore chips cost them 0.5-0.7pp in yearly total factor productivity growth. These losses are permanent, and without adaptation would reflect a lower long-term growth rate for these firms. These findings may help explain larger observed declines in the productivity growth of users of information technology. 1 I would like to thank my PhD advisors David Mowery, Lee Fleming, Brian Wright and Bronwyn Hall for excellent support and advice over the years. Thanks also to Philip Stark for his statistical guidance. This work would not have been possible without the help of computer scientists Horst Simon (Lawrence Berkeley National Lab) and Jim Demmel, Kurt Keutzer, and Dave Patterson in the Berkeley Parallel Computing Lab, I gratefully acknowledge their overall guidance, their help with the Berkeley Software Parallelism Survey and their hospitality in letting me be part of their lab. -

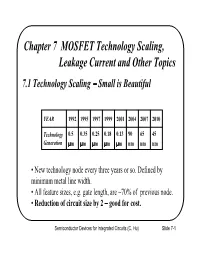

MOSFET Technology Scaling, Leakage Current, and Other Topics

Chapter 7 MOSFET Technology Scaling, Leakage Current and Other Topics 7.1 Technology Scaling Small is Beautiful YEAR 1992 1995 1997 1999 2001 2004 2007 2010 Technology 0.5 0.35 0.25 0.18 0.13 90 65 45 Generation µµµm µµµm µµµm µµµm µµµm nm nm nm • New technology node every three years or so. Defined by minimum metal line width. • All feature sizes, e.g. gate length, are ~70% of previous node. • Reduction of circuit size by 2 good for cost. Semiconductor Devices for Integrated Circuits (C. Hu) Slide 7-1 International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors, 1999 Edition Year of Shipment 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2014 DRAM metal half pitch 180 130 100 70 50 35 (nm) MPU physical Lg (nm) 140 85 65 45 32 22 Tox (nm) 1.5-1.8 1.5-1.9 1-1.5 0.8-1.2 0.6-0.8 0.5-0.6 VDD 1.5-1.8 1.2-1.5 0.9-1.2 0.6-0.9 0.5-0.6 0.3-0.6 µµµ µµµ Ion,HP ( A/ m) 750/350 750/350 750/350 750/350 750/350 750/350 µµµ Ioff,HP (nA/ m) 5 10 20 40 60 160 µµµ µµµ Ion,LP ( A/ m) 490/230 490/230 490/230 490/230 490/230 490/230 µµµ Ioff,LP (pA/ m) 7 10 20 40 80 160 No known solutions •Vdd is reduced at each node to contain power consumption in spite of rising transistor density and frequency •Tox is reduced to raise I on for speed consideration Semiconductor Devices for Integrated Circuits (C. -

Extraction of Front and Buried Oxide Interface Trap Densities in Fully

Q32 ECS Solid State Letters, 2 (5) Q32-Q34 (2013) 2162-8742/2013/2(5)/Q32/3/$31.00 © The Electrochemical Society Extraction of Front and Buried Oxide Interface Trap Densities in Fully Depleted Silicon-On-Insulator Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistor Jen-Yuan Cheng,z Chun Wing Yeung, and Chenming Hu Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, California 94720, USA In this letter, a method is proposed and demonstrated for the first time to characterize and decouple the interface traps of both the front- and back channels of fully-depleted silicon-on-insulator (FD-SOI) metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET). We report the procedure and the underlying theory that allows the extraction of the energy profiles of the densities of the interface traps (Dit).This technique will be very useful for evaluating the interface qualities of future FD-SOI transistors. © 2013 The Electrochemical Society. [DOI: 10.1149/2.001305ssl] All rights reserved. Manuscript submitted December 31, 2012; revised manuscript received January 28, 2013. Published February 12, 2013. The fully-depleted silicon on insulator (FD-SOI) ultra-thin body channels in FD-SOI, the corresponding surface potentials for front 1–3 UTBSOI MOSFET is gaining new attention as an alternative tech- and back channel interface φsF and φsB with respect to the applied nology to FinFET4 for ultra-low power and mobile applications be- front and back bias can be expressed as follows19,20 cause of its outstanding -

Nanoelectronics

Highlights from the Nanoelectronics for 2020 and Beyond (Nanoelectronics) NSI April 2017 The semiconductor industry will continue to be a significant driver in the modern global economy as society becomes increasingly dependent on mobile devices, the Internet of Things (IoT) emerges, massive quantities of data generated need to be stored and analyzed, and high-performance computing develops to support vital national interests in science, medicine, engineering, technology, and industry. These applications will be enabled, in part, with ever-increasing miniaturization of semiconductor-based information processing and memory devices. Continuing to shrink device dimensions is important in order to further improve chip and system performance and reduce manufacturing cost per bit. As the physical length scales of devices approach atomic dimensions, continued miniaturization is limited by the fundamental physics of current approaches. Innovation in nanoelectronics will carry complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technology to its physical limits and provide new methods and architectures to store and manipulate information into the future. The Nanoelectronics Nanotechnology Signature Initiative (NSI) was launched in July 2010 to accelerate the discovery and use of novel nanoscale fabrication processes and innovative concepts to produce revolutionary materials, devices, systems, and architectures to advance the field of nanoelectronics. The Nanoelectronics NSI white paper1 describes five thrust areas that focus the efforts of the six participating agencies2 on cooperative, interdependent R&D: 1. Exploring new or alternative state variables for computing. 2. Merging nanophotonics with nanoelectronics. 3. Exploring carbon-based nanoelectronics. 4. Exploiting nanoscale processes and phenomena for quantum information science. 5. Expanding the national nanoelectronics research and manufacturing infrastructure network. -

Leakage Current and Breakdown Electric-Field Studies on Ultrathin

APPLIED PHYSICS LETTERS 87, 182904 ͑2005͒ Leakage current and breakdown electric-field studies on ultrathin atomic-layer-deposited Al2O3 on GaAs ͒ H. C. Lin and P. D. Yea School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 G. D. Wilk Advanced Semiconductor Materials (ASM) America, 3440 East University Drive, Phoenix, Arizona 85034 ͑Received 29 June 2005; accepted 1 September 2005; published online 25 October 2005͒ Atomic-layer deposition ͑ALD͒ provides a unique opportunity to integrate high-quality gate dielectrics on III-V compound semiconductors. We report detailed leakage current and breakdown electric-field characteristics of ultrathin Al2O3 dielectrics on GaAs grown by ALD. The leakage current in ultrathin Al2O3 on GaAs is comparable to or even lower than that of state-of-the-art SiO2 on Si, not counting the high-k dielectric properties for Al2O3. A Fowler-Nordheim tunneling analysis on the GaAs/Al2O3 barrier height is also presented. The breakdown electric field of Al2O3 is measured as high as 10 MV/cm as a bulk property. A significant enhancement on breakdown electric field up to 30 MV/cm is observed as the film thickness approaches to 1 nm. © 2005 American Institute of Physics. ͓DOI: 10.1063/1.2120904͔ Al2O3 is a widely used insulating material for gate di- sured as high as 10 MV/cm for films thicker than 50 Å, electric, tunneling barrier, and protection coating due to its which is near the bulk breakdown electric field for ALD excellent dielectric properties, strong adhesion to dissimilar Al2O3. A significant enhancement on breakdown electric materials, and its thermal and chemical stabilities. -

FAQ: Sic MOSFET Application Notes

FAQ SiC MOSFET Description This document introduces the Frequently Asked Questions and answers of SiC MOSFET. © 20 21 2021-3-22 Toshiba Electronic Devices & Storage Corporation 1 Table of Contents Description .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures / List of Tables ................................................................................................................................ 3 1. What is SiC ? ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Is it possible to connect multiple SiC MOSFETs in parallel ? ........................................................................... 5 ............................................................................... 6 .................................................................................... 7 5. If Si IGBT replaced with SiC MOSFET, what will change ? ............................................................................. 8 6. Is there anything to note about the Gate drive voltage ? ..................................................................................... 9 RESTRICTIONS ON PRODUCT USE .............................................................................................................. -

The Bottom-Up Construction of Molecular Devices and Machines*

Pure Appl. Chem., Vol. 80, No. 8, pp. 1631–1650, 2008. doi:10.1351/pac200880081631 © 2008 IUPAC Nanoscience and nanotechnology: The bottom-up construction of molecular devices and machines* Vincenzo Balzani‡ Department of Chemistry “G. Ciamician”, University of Bologna, 40126 Bologna, Italy Abstract: The bottom-up approach to miniaturization, which starts from molecules to build up nanostructures, enables the extension of the macroscopic concepts of a device and a ma- chine to molecular level. Molecular-level devices and machines operate via electronic and/or nuclear rearrangements and, like macroscopic devices and machines, need energy to operate and signals to communicate with the operator. Examples of molecular-level photonic wires, plug/socket systems, light-harvesting antennas, artificial muscles, molecular lifts, and light- powered linear and rotary motors are illustrated. The extension of the concepts of a device and a machine to the molecular level is of interest not only for basic research, but also for the growth of nanoscience and the development of nanotechnology. Keywords: molecular devices; molecular machines; information processing; photophysics; miniaturization. INTRODUCTION Nanotechnology [1–8] is a frequently used word both in the scientific literature and in the common lan- guage. It has become a favorite, and successful, term among America’s most fraudulent stock promot- ers [9] and, in the venture capital world of start-up companies, is perceived as “the design of very tiny platforms upon which to raise enormous amounts of money” [1]. Indeed, nanotechnology is a word that stirs up enthusiasm or fear since it is expected, for the good or for the bad, to have a strong influence on the future of mankind. -

Analyzing the Effect of Gate Dielectric on the Leakage Currents

MATEC Web of Conferences57, 01028 (2016) DOI: 10.1051/matecconf/2016 57 01028 ICAET - 2016 Analyzing the effect of gate dielectric on the leakage currents Sakshi, Sandeep Dhariwal and Amandeep Singh Lovely Professional University- Phagwara, India Abstract. An analytical threshold voltage model for MOSFETs has been developed using different gate dielectric oxides by using MATLAB software. This paper explains the dependency of threshold voltage on the dielectric material. The variation in the subthreshold currents with the change in the threshold voltage sue to the change of dielectric material has also been studied. Index Terms— threshold voltage, gate dielectric oxides, subthreshold currents Basic material properties which are important for the selection of alternative gate dielectric are dielectric permittivity, band gap, band alignment with respect to 1 INTRODUCTION silicon, thermodynamic stability, film morphology and Earlier the VLSI designers were mainly concerned about uniformity, interface quality, and reliability [4]. the performance and miniaturization of the VLSI devices. For the last few years, power dissipation has been a serious issue because of the significant growth in portable computing and wireless communication. For more than 40 years, silicon dioxide has been used as dielectric because of its manufacturability and providing a continuous improved transistor performance as it is grown thinner and thinner [1-2]. The scaling of gate dielectric is done to improve the MOS transistor performance. The continuous scaling down of physical thickness of the gate dielectric and gate length has improved device performance and increased packing densities. Because of continuous scaling, the silicon dioxide dielectric thickness has been reduced to such an extent that further scaling will lead to increase in poly- Si gate depletion, gate dopant penetration, power consumption, etc. -

Micromanufacturing and Fabrication of Microelectronic Devices

Micromanufacturing and Fabrication of Microelectronic PART Devices •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••V The importance of the topics covered in the following two chapters can best be appreciated by considering the manufacture of a simple metal spur gear. It is impor- tant to recall that some gears are designed to transmit power, such as those in gear boxes, yet others transmit motion, such as in rack and pinion mechanisms in auto- mobile steering systems. If the gear is, say, 100 mm (4 in.) in diameter, it can be produced by traditional methods, such as starting with a cast or forged blank, and machining and grinding it to its final shape and dimensions. A gear that is only 2 mm (0.080 in.) in diameter, on the other hand, can be difficult to produce by these meth- ods. If sufficiently thin, the gear could, for example, be made from sheet metal, by fine blanking, chemical etching, or electroforming. If the gear is only a few micrometers in size, it can be produced by such tech- niques as optical lithography, wet and dry chemical etching, and related processes. A gear that is only a nanometer in diameter would, however, be extremely difficult to produce; indeed, such a gear would have only a few tens of atoms across its surface. The challenges faced in producing gears of increasingly smaller sizes is highly informative, and can be put into proper perspective by referring to the illustration of length scales shown in Fig. V.1. Conventional manufacturing processes, described in Chapters 11 through 27, typically produce parts that are larger than a millimeter or so, and can be described as visible to the naked eye.