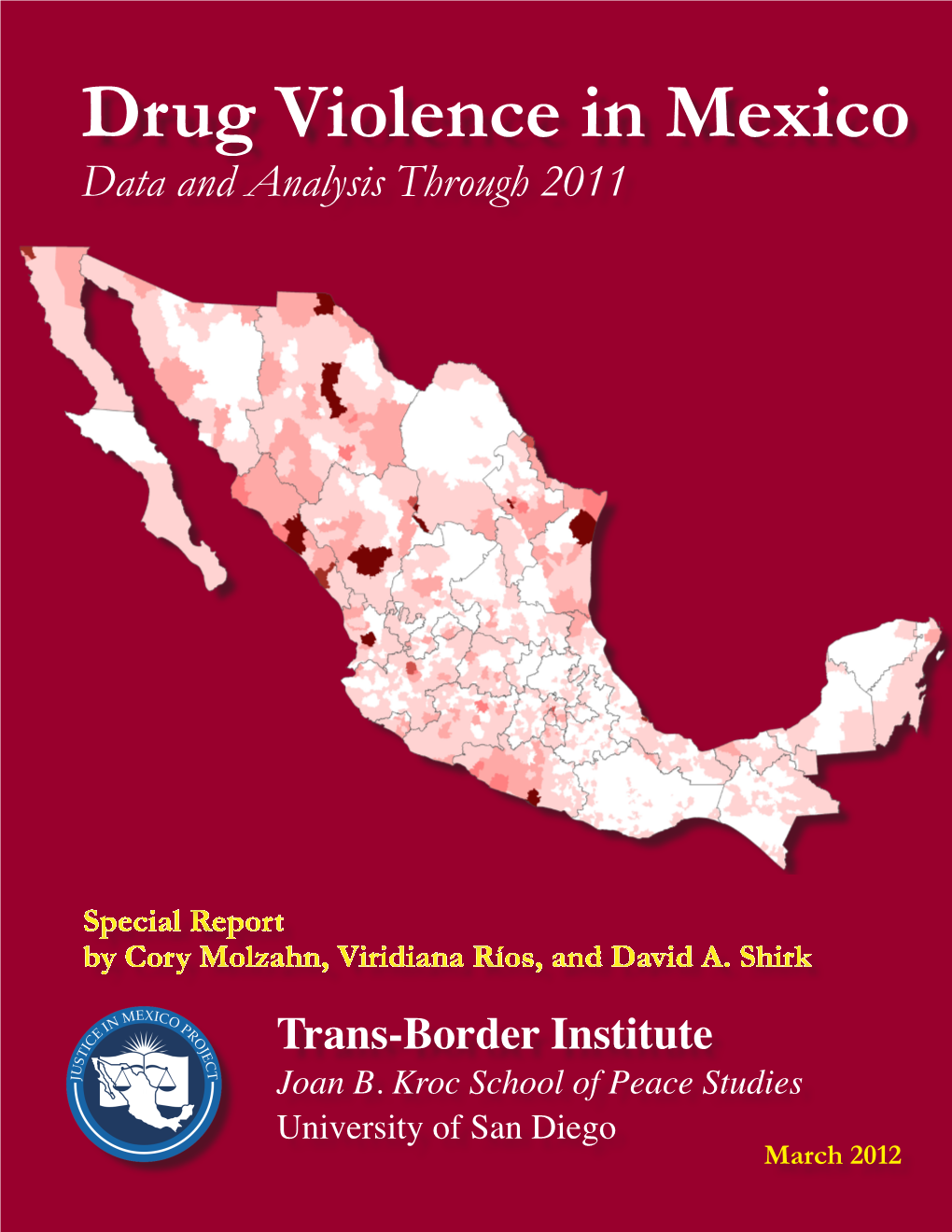

Drug Violence in Mexico Data and Analysis Through 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Pdf], Fecha De Consulta: 1 De Abril De 2014](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5926/pdf-fecha-de-consulta-1-de-abril-de-2014-205926.webp)

Pdf], Fecha De Consulta: 1 De Abril De 2014

UNIVErsidad auTÓNOMA METROPOLITana Rector general: Eduardo Abel Peñalosa Castro Secretario general: José Antonio de los Reyes Heredia UNIVErsidad auTÓNOMA METROPOLITana-XOCHIMILCO Rector: Fernando de León González Secretaria: Claudia Mónica Salazar Villava DIVISIÓN DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Y HumanidadES Director: Carlos Alfonso Hernández Gómez Secretario académico: Alfonso León Pérez Jefe de la Sección de Publicaciones: Miguel Ángel Hinojosa Carranza ISSN: 0187-5795 DR © 2017 universidad autónoma metropolitana Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco Calzada del Hueso 1100 Colonia Villa Quietud, Coyoacán 04960, México DF Argumentos. Estudios críticos de la sociedad, número 85, septiembre-diciembre 2017, es una publicación cuatrimestral editada por la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana a través de la Unidad Xochimilco, División de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Prolongación Canal de Miramontes 3855, Col. Ex-Hacienda San Juan de Dios, Delegación Tlapan, C.P. 14387, Ciudad de México; y Calzada del Hueso 1100, Colonia Villa Quietud, Delegación Coyoacán, C.P. 04960, Ciudad de México. Página electrónica: http://argumentos.xoc.uam.mx y dirección electrónica: [email protected]. Editor responsable: Francisco Luciano Concheiro Bórquez. Certificado de Reserva de Derechos al Uso Exclusivo de Título No. 04-1999-110316080100-102, ISSN 0187-5795, otorgado por el Instituto Nacional del Derecho de Autor. Certificado de Licitud de Título número 5303 y Certificado de Licitud de Contenido número 4083, ambos otorgados por la Comisión Calificadora de Publicaciones y Revistas Ilustradas de la Secretaría de Gobernación. Impresa por mc editores, Selva 53-204, Colonia Insurgentes Cuicuilco, Delegación Coyoacán, C.P. 04530, Ciudad de México, Tel. (52) (55) 56 65 71 63, [email protected]. Distribución: librería de la UAM-Xochimilco, Edificio Central, planta baja, tels. -

The Politics of Crime in Mexico: Democratic Governance in a Security Trap

EXCERPTED FROM The Politics of Crime in Mexico: Democratic Governance in a Security Trap John Bailey Copyright © 2014 ISBN: 978-1-935049-89-0 hc FIRSTFORUMPRESS A DIVISION OF LYNNE RIENNER PUBLISHERS, INC. 1800 30th Street, Ste. 314 Boulder, CO 80301 USA telephone 303.444.6684 fax 303.444.0824 This excerpt was downloaded from the FirstForumPress website www.firstforumpress.com Contents List of Tables and Figures ix Preface xi 1 Security Traps and Mexico’s Democracy 1 2 Foundational Crime: Tax Evasion and Informality 31 3 Common Crime and Democracy: Weakening vs. Deepening 51 4 Organized Crime: Theory and Applications to Kidnapping 85 5 Drug Trafficking Organizations and Democratic Governance 115 6 State Responses to Organized Crime 143 7 Escape Routes: Policy Adaptation and Diffusion 181 List of Acronyms 203 Bibliography 207 Index 225 vii 1 Security Traps and Mexico’s Democracy “We either sort this out or we’re screwed. Really screwed.” —Javier 1 Sicilia, April 2011. “May the Mexican politicians forgive me, but the very first thing is to construct a state policy. The fight against drugs can’t be politicized.” —Former Colombian President Ernesto Samper, June 2011.2 The son of Javier Sicilia, a noted Mexican poet and journalist, was among seven young people found murdered in Cuernavaca, Morelos, in late March 2011. The scandal triggered mega-marches in 37 cities throughout Mexico to protest violence and insecurity. Like others before him, Sicilia vented his rage at the political class. “We’ve had legislators that do nothing more than collect their pay. And that’s the real complaint of the people. -

Secretaria De Seguridad Public

ÍNDICE PRESENTACIÓN ................................................................................................................................................................5 INTRODUCCIÓN ...............................................................................................................................................................7 I. ACCIONES Y RESULTADOS .......................................................................................................................................9 1. ALINEAR LAS CAPACIDADES DEL ESTADO MEXICANO CONTRA LA DELINCUENCIA ..................... 11 1.1 REFORMAS AL MARCO LEGAL .............................................................................................................. 11 1.2 COOPERACIÓN ENTRE INSTITUCIONES POLICIALES ..................................................................... 13 1.3 DESARROLLO POLICIAL ........................................................................................................................... 14 1.4 INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPAMIENTO POLICIAL .......................................................................... 20 1.5 INTELIGENCIA Y OPERACIÓN POLICIAL ............................................................................................. 21 1.6 COOPERACIÓN INTERNACIONAL ......................................................................................................... 36 1.7 SERVICIO DE PROTECCIÓN FEDERAL ................................................................................................. 39 2. -

Mexican Drug Wars Update: Targeting the Most Violent Cartels

MEXICAN DRUG WARS UPDATE: Targeting the Most Violent Cartels July 21, 201 1 This analysis may not be forwarded or republished without express permission from STRATFOR. For permission, please submit a request to [email protected]. 1 STRATFOR 700 Lavaca Street, Suite 900 Austin, TX 78701 Tel: 1-512-744-4300 www.stratfor.com Mexican Drug Wars Update: Targeting the Most Violent Cartels Editor’s Note: Since the publication of STRATFOR’s 2010 annual Mexican cartel report, the fluid nature of the drug war in Mexico has prompted us to take an in-depth look at the situation more frequently. This is the second product of those interim assessments, which we will now make as needed, in addition to our annual year-end analyses and our weekly security memos. As we suggested in our first quarterly cartel update in April, most of the drug cartels in Mexico have gravitated toward two poles, one centered on the Sinaloa Federation and the other on Los Zetas. Since that assessment, there have not been any significant reversals overall; none of the identified cartels has faded from the scene or lost substantial amounts of territory. That said, the second quarter has been active in terms of inter-cartel and military-on-cartel clashes, particularly in three areas of Mexico: Nuevo Leon, Tamaulipas and Veracruz states; southern Coahuila, through Durango, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosi and Aguascalientes states; and the Pacific coast states of Nayarit, Jalisco, Michoacan and Guerrero. There are three basic dimensions of violence in Mexico: cartel vs. cartel, cartel vs. government and cartel vs. -

To Defenders:Women Confronting Violence in Mexico, Honduras

Nobel Women’s Initiative A from survivors Women Confronting Violence in to defenders: Mexico, Honduras & Guatemala Advocating for peace, justice & equality B Nobel Women’s Initiative acknowledgements This report would not be possible without the remarkable and courageous work of many women in Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala who face violence and threats daily. We dedicate it to them. We would also like to thank the host committees who welcomed us into their countries and facilitated our visit, shared their extensive knowledge on the issues facing women in the region, and who contributed so much hard work and thoughtful planning to ensure our visit would have the most impact possible. We gratefully acknowledge the writing and analysis of Laura Carlsen, who wrote this report and so eloquently helped us to share the experiences of the delegation and the women we met. We thank the following for their generous support of this delegation: t MDG3 Fund and Funding Leadership and Opportunities for Women (FLOW) of the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs t Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs t UN Women, Latin American and Caribbean Section Cynda Collins Arsenault Sara Vetter Sarah Cavanaugh Kay Wilemon Lauren Embrey Nancy and Emily Word Jeddah Mali Trea Yip Concept and Design: Green Communication Design inc. www.greencom.ca Nobel Women’s Initiative 1 table of contents Letter From Nobel Peace Laureates 02 Jody Williams & Rigoberta Menchú Tum I. Introduction: 04 Bearing Witness to Violence Against Women II. Findings: 06 Violence Against Women: Reaching Crisis Proportions III. In Defense of the Defensoras 10 Mexico, Honduras and Guatemala: High-Risk Countries for Women and Women’s Rights Defenders 14 IV. -

No Veo, No Hablo Y No Escucho : Retrato Del Periodismo Veracruzano

Universidad de San Andrés Departamento de Ciencias Sociales Maestría en Periodismo No veo, no hablo y no escucho : retrato del periodismo veracruzano Autor: Alfaro Vega, Dora Iveth Legajo: 0G05763726 Director de Tesis: Vargas, Inti | Castells i Talens, Antoni México, 2 de marzo de 2018 1 Universidad de San Andrés y Grupo Clarín Maestría en Periodismo. Dora Iveth Alfaro Vega. “No veo, no hablo y no escucho: retrato del periodismo veracruzano”. Tutores: Inti Vargas y Antoni Castells i Talens. México a 2 de marzo de 2018. 2 PARTE 1: INVESTIGACIÓN PERIODÍSTICA ______________________________ 3 Justificación: el trayecto _________________________________________________________________ 3 El adiós. No veo, no hablo y no escucho _____________________________________________________ 8 Unas horas antes ______________________________________________________________________ 16 ¿Por qué? ____________________________________________________________________________ 30 México herido _______________________________________________________________________ 30 Tierra de periodistas muertos ___________________________________________________________ 31 Los primeros atentados ________________________________________________________________ 32 Prueba y error: adaptándose a la violencia _________________________________________________ 35 Nóminas y ‘paseos’ __________________________________________________________________ 37 Los mensajes________________________________________________________________________ 43 Milo Vela y su familia ________________________________________________________________ -

Veracruz Reporter Becomes Fifth Journalist Killed in Mexico in 2011 by Carlos Navarro Category/Department: Human Rights Published: Wednesday, August 3, 2011

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository SourceMex Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 8-3-2011 Veracruz Reporter Becomes Fifth ourJ nalist Killed in Mexico in 2011 Carlos Navarro Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sourcemex Recommended Citation Navarro, Carlos. "Veracruz Reporter Becomes Fifth ourJ nalist Killed in Mexico in 2011." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ sourcemex/5813 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in SourceMex by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 078262 ISSN: 1054-8890 Veracruz Reporter Becomes Fifth Journalist Killed in Mexico in 2011 by Carlos Navarro Category/Department: Human Rights Published: Wednesday, August 3, 2011 The murder of journalist Yolanda Ordaz de la Cruz in Veracruz state this year caused a greater outcry than most recent killings of reporters and editors in Mexico. The death of Ordaz was another reminder of the perils that writers, editors, publishers, and other editorial employees have to face as part of their jobs. But the case became even more controversial because of comments made by state attorney general Reynaldo Escobar Pérez in the aftermath of the killing. Escobar suggested that Ordaz was probably killed because of her connections to organized crime and not because of her reporting. Ordaz, a police reporter for the statewide newspaper , was the fifth journalist killed in Mexico this year. She was the second reporter and third editorial employee of killed in recent weeks in Veracruz. -

Mexico Is Not at War. It Is a Democracy. and Yet It Is One of the World's Most Dangerous Countries for the Press. Twenty-One J

June 7, 2008 Mexico is not at war. It is a democracy. And yet it is one of the world’s most dangerous countries for the press. Twenty-one journalists have been killed in Mexico since 2000, seven of them in direct reprisal for their work. Since 2005, seven others have gone missing. Mexico ranks 10th on CPJ’s impunity index, along with such war-ravaged countries as Iraq, Somalia, and Sierra Leone. The impact of this unchecked record of violence is well known and well documented. Fear permeates newsrooms and broad self-censorship is the result. In border cities, where the drug cartels hold sway, gunbattles in the middle of downtown go unreported. There is little doubt that organized crime associated with the drug trade is responsible for much of the violence against the press. But the failure of the Mexican government to fully investigate these crimes and bring the perpetrators to justice has created a culture of impunity that perpetuates the cycle of violence. CPJ commissioned this report because we wanted to take a close look at the factors that prevent these cases from being solved. CPJ Mexico representative Monica Campbell has assembled dossiers on three emblematic cases—the killings of journalists Francisco Ortiz Franco in Tijuana, Bradley Will in Oaxaca, and Amado Ramírez Dillanes in Acapulco. The circumstances of these killings were very different, as were the initial investigations. But all three shared certain characteristics. In Mexico, murder is a state crime and state prosecutors handled the initial investigations in all three cases. Because of shoddy police work, fear, or political pressure, the investigations failed to move forward. -

South Pacific Cartel Author: Guillermo Vazquez Del Mercado Review: Phil Williams

Organization Attributes Sheet: South Pacific Cartel Author: Guillermo Vazquez del Mercado Review: Phil Williams A. When the organization was formed + brief history The organization is the strongest splinter of what used to be called the Beltran Leyva Organization which was once part of The Federation, but seceded in 2008 after the arrest of Alfredo.1 It is headed by Hector Beltran Leyva (AKA: “El H”) who is the only Beltran Leyva brother who is still performing criminal activities (Arturo AKA: “El Barbas” was killed in December 2009 in operation headed by the Mexican Navy that attempted to arrest him and Alfredo AKA: “El Mochomo” was arrested in January 2008) It gained relevance after the arrests of Sergio Villareal Barragan (AKA: “El Grande”) and Edgar Valdez Villarreal (AKA: “La Barbie”), who were disputing the leadership of the organization after Arturo Beltran was killed. The arrests made it easier for Hector to rebuild the organization without his leadership being challenged and routes being disputed any longer.2 This organization is also known for the reckless violence their hit man groups (teenagers and under age boys) generate in those areas under its control or disputed by other organizations. B. Types of illegal activities engaged in, a. In general The organization’s recent creation makes it difficult to determine precisely what their illicit activities are, but it can be presumed that it is still engaging in the activities familiar to the Beltran Leyva Organization: smuggling cocaine, marijuana and heroin, as well as people trafficking, money laundering, extortion, kidnapping, contract hits and arms trafficking.3 b. -

Volume 210 Winter 2011 ARTICLES SHAKEN BABY SYNDROME

Volume 210 Winter 2011 ARTICLES SHAKEN BABY SYNDROME: DAUBERT AND MRE 702’S FAILURE TO EXCLUDE UNRELIABLE SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE AND THE NEED FOR REFORM Major Elizabeth A. Walker A NEW WAR ON AMERICA’S OLD FRONTIER: MEXICO’S DRUG CARTEL INSURGENCY Major Nagesh Chelluri THE TWENTY-SEVENTH GILBERT A. CUNEO LECTURE IN GOVERNMENT CONTRACT LAW Daniel I. Gordon BOOK REVIEWS Department of Army Pamphlet 27-100-210 MILITARY LAW REVIEW Volume 210 Winter 2011 CONTENTS ARTICLES Shaken Baby Syndrome: Daubert and MRE 702’s Failure to Exclude Unreliable Scientific Evidence and the Need for Reform Major Elizabeth A. Walker 1 A New War on America’s Old Frontier: Mexico’s Drug Cartel Insurgency Major Nagesh Chelluri 51 The Twenty-Seventh Gilbert A. Cuneo Lecture in Government Contract Law Daniel I. Gordon 103 BOOK REVIEWS Law in War, War as Law: Brigadier General Joseph Holt and the Judge Advocate General’s Department in the Civil War and Early Reconstruction, 1861–1865 and Lincoln’s Forgotten Ally: Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt of Kentucky Reviewed by Fred L. Borch III 113 The Reluctant Communist: My Desertion, Court-Martial, and Forty- Year Imprisonment in North Korea Reviewed by Major Clay A. Compton 122 On China Reviewed by Lieutenant Commander Todd Kline 130 i Headquarters, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C. Pamphlet No. 27-100-210, Winter 2011 MILITARY LAW REVIEW—VOLUME 210 Since 1958, the Military Law Review has been published at The Judge Advocate General’s School, U.S. Army, Charlottesville, Virginia. The Military Law Review provides a forum for those interested in military law to share the products of their experience and research, and it is designed for use by military attorneys in connection with their official duties. -

Confrontations Codebook MAIN TABLE. CONFRONTATIONS (A-E)

Confrontations Codebook MAIN TABLE. CONFRONTATIONS (A-E) Variable Name Description Values abbreviatio n ID ID Unique ID {1…9999} TIMESTAM TIMESTAMP Unique ID for time {1…9999999999} P DAY DAY Day {1… 31} MONTH MONTH Month {1…12} YEAR YEAR Year {2006…2011} STATE STATE State (INEGI code) {1…32} MUNICIPAL MUNICIPALITY Municipality (INEGI code) {1…999} ITY Sin determinar: 9999 DETAINEES DETAINEES Number of detainees {0…999} KILLED KILLED Number of persons killed {0…999} ARMY_K SOLDIERS KILLED Number of members of the Army killed {0…999} NAVY_K MARINES KILLED Number of members of the Navy killed {0…999} FP_K FEDERAL POLICE Number of federal police officers killed {0…999} KILLED AFI_K AFI/ FEDERAL Number of AFI/ federal police detectives {0…999} POLICE DETECTIVES killed KILLED SP_K STATE POLICE Number of state police officers killed {0…999} KILLED MINP_K POLICE DETECTIVE Number of police detectives killed {0…999} KILLED MUNP_K MUNICIPAL POLICE Number of municipal police officers killed {0…999} KILLED ATTOR_K PROSECUTORS Number of prosecutors killed {0…999} KILLED OC_K ORGANIZED Number of organized crime members {0…999} CRIMINALS KILLED killed CIV_K CIVILIANS KILLED Number of civilians (or not specified) {0…999} killed WOUNDED WOUNDED Number of wounded individuals {0…999} INDIVIDUALS ARMY_W MILITARY Number of members of the Army wounded {0…999} WOUNDED NAVY_W MARINES Number of members of the Navy wounded {0…999} WOUNDED FP_W FEDERAL POLICE Number of federal police officers wounded {0…999} WOUNDED AFI_W AFI/ MINISTERIAL Number of AFI/ federal -

Mexico's Drug Trafficking Organizations

Mexico’s Drug Trafficking Organizations: Source and Scope of the Rising Violence June S. Beittel Analyst in Latin American Affairs September 7, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41576 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Mexico’s Drug Trafficking Organizations: Source and Scope of the Rising Violence Summary The violence generated by Mexico’s drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) in recent years has been unprecedented. In 2006, Mexico’s newly elected President Felipe Calderón launched an aggressive campaign against the DTOs—an initiative that has defined his administration—that has been met with a violent response from the DTOs. Government enforcement efforts have successfully removed some of the key leaders in all of the seven major DTOs, either through arrests or deaths in operations to detain them. However, these efforts have led to succession struggles within the DTOs themselves that generated more violence. According to the Mexican government’s estimate, organized crime-related violence claimed more than 34,500 lives between January 2007 and December 2010. By conservative estimates, there have been an additional 8,000 homicides in 2011 increasing the number of deaths related to organized crime to over 40,000 since President Calderón came to office in late 2006. Although violence has been an inherent feature of the trade in illicit drugs, the character of the drug trafficking-related violence in Mexico has been increasingly brutal. In 2010, several politicians were murdered, including a leading gubernatorial candidate in Tamaulipas and 14 mayors. At least 10 journalists were killed last year and five more were murdered through July 2011.