Volume 210 Winter 2011 ARTICLES SHAKEN BABY SYNDROME

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring the Relationship Between Militarization in the United States

Exploring the Relationship Between Militarization in the United States and Crime Syndicates in Mexico: A Look at the Legislative Impact on the Pace of Cartel Militarization by Tracy Lynn Maish A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Criminology and Criminal Justice) in the University of Michigan-Dearborn 2021 Master Thesis Committee: Assistant Professor Maya P. Barak, Chair Associate Professor Kevin E. Early Associate Professor Donald E. Shelton Tracy Maish [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8834-4323 © Tracy L. Maish 2021 Acknowledgments The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of their committee and the impact that their guidance had on the process. Without the valuable feedback and enormous patience, this project would not the where it is today. Thank you to Dr. Maya Barak, Dr. Kevin Early, and Dr. Donald Shelton. Your academic mentorship will not be forgotten. ii Table of Contents 1. Acknowledgments ii 2. List of Tables iv 3. List of Figures v 4. Abstract vi 5. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 6. Chapter 2 The Militarization of Law Enforcement Within the United States 8 7. Chapter 3 Cartel Militarization 54 8. Chapter 4 The Look into a Mindset 73 9. Chapter 5 Research Findings 93 10. Chapter 6 Conclusion 108 11. References 112 iii List of Tables Table 1 .......................................................................................................................................... 80 Table 2 ......................................................................................................................................... -

Shaken Baby Syndrome I Blumenthal

732 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.78.926.732 on 1 December 2002. Downloaded from REVIEW Shaken baby syndrome I Blumenthal ............................................................................................................................. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:732–735 Shaken baby syndrome is the most common cause of shaking as a technique for stopping the child death or serious neurological injury resulting from child crying.7 Such individuals are most frequently male, fathers, boyfriends, and babysitters.89 abuse. It is specific to infancy, when children have unique anatomic features. Subdural and retinal haemorrhages are markers of shaking injury. An PATHOPHYSIOLOGY American radiologist, John Caffey, coined the name The forces needed for a head injury are transla- tional or rotational. Translational forces produce whiplash shaken infant syndrome in 1974. It was, linear movement of the brain. Such forces occur however, a British neurosurgeon, Guthkelch who first during falls and at worst cause a skull fracture, described shaking as the cause of subdural but are usually relatively benign. Rotational forces, which occur during shaking, cause the haemorrhage in infants. Impact was later thought to brain to turn on its central axis or at the play a major part in the causation of brain damage. attachment to the brainstem. Movement of the Recently improved neuropathology and imaging brain within the subdural space causes stretching and tearing of the bridging veins, which extend techniques have established the cause of brain injury as from the cortex to the dural venous sinus. The loss hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Diffusion weighted of blood, typically 2–15 ml, into the subdural 7 magnetic resonance imaging is the most sensitive and space is not of itself harmful. -

Blueprint for Southern Border Security

Blueprint for Southern Border Security Chairman Michael T. McCaul Committee on Homeland Security U.S. House of Representatives Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Vision for Border Security .............................................................................................................. 3 Achieve Full Situational Awareness ........................................................................................... 3 Develop Outcome Based Metrics ............................................................................................... 5 Enforce Strong Penalties ............................................................................................................. 6 Leverage State, Local and Tribal Law Enforcement .................................................................. 7 Enhance Command and Control ................................................................................................. 7 Engage Internationally ................................................................................................................ 8 San Diego .................................................................................................................................. 10 El Centro ................................................................................................................................... 13 Yuma ........................................................................................................................................ -

In the Shadow of Saint Death

In the Shadow of Saint Death The Gulf Cartel and the Price of America’s Drug War in Mexico Michael Deibert An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK Copyright © 2014 by Michael Deibert First Lyons Paperback Edition, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available The Library of Congress has previously catalogued an earlier (hardcover) edition as follows: Deibert, Michael. In the shadow of Saint Death : the Gulf Cartel and the price of America’s drug war in Mexico / Michael Deibert. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7627-9125-5 (hardback) 1. Drug traffic—Mexican-American Border Region. 2. Drug dealers—Mexican-American Border Region. 3. Cartels—Mexican-American Border Region. 4. Drug control—Mexican- American Border Region. 5. Drug control—United States. 6. Drug traffic—Social aspects— Mexican-American Border Region. 7. Violence—Mexican-American Border Region. 8. Interviews—Mexican-American Border Region. 9. Mexican-American Border Region—Social conditions. I. Title. HV5831.M46D45 2014 363.450972—dc23 2014011008 ISBN 978-1-4930-0971-8 (pbk.) ISBN 978-1-4930-1065-3 (e-book) The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence -

Shaken Baby Syndrome Is 100% Preventable Shaken Baby

Shaken Baby Syndrome is 100% preventable Everyday handling of a baby, playful acts and minor accidents do not have the force needed to create these injuries. Shaking injuries are NOT caused by: BOUNCING BABY ON YOUR KNEE GENTLY TOSSING BABY IN THE AIR JOGGING OR BIKING WITH YOUR BABY FALLS OFF OF FURNITURE Shaken Baby Syndrome facts Shaken Baby Syndrome (SBS) is one of the most common causes of death by physical abuse to infants. Produced and distributed In accordance with Violent shaking causes bleeding and massive the Kimberlin West Act. swelling in the brain and can result in: n Permanent brain damage For more information visit the Florida n Blindness Department of Health website. n Developmental Delays n Cerebral Palsy n Seizures n Death Did you know? Shaken Baby Syndrome occurs when a frustrated caregiver loses control and violently shakes an infant or young child. Crying is the most common reason that someone severely shakes a baby. Young males who care for a baby alone are most at risk to shake a baby. WHY BABIES CRY n hunger n too hot or too cold n diaper needs changing n discomfort/pain, fever/illness n teething n colic n n boredom/over-stimulation n fear—of loud noises or stranger n Understanding your baby Ways to calm your baby Ways to handle your Taking care of your baby can be fun and It may seem like your baby cries more than enjoyable. But, when your baby won’t stop others, but ALL babies cry, some even cry a lot. frustration crying, it can be very upsetting for you and You can do the following things to try and sooth When your baby is crying. -

Overcoming Defense Expert Testimony in Abusive Head Trauma Cases

NATIONAL CENTER FOR PROSECUTION OF CHILD ABUSE Special Topics in Child Abuse Overcoming Defense Expert Testimony in Abusive Head Trauma Cases By Dermot Garrett Edited by Eleanor Odom, Amanda Appelbaum and David Pendle NATIONAL CENTER FOR PROSECUTION OF CHILD ABUSE Scott Burns Director , National District Attorneys Association The National District Attorneys Association is the oldest and largest professional organization representing criminal prosecutors in the world. Its members come from the offices of district attorneys, state’s attorneys, attorneys general, and county and city prosecutors with responsibility for prosecuting criminal violations in every state and territory of the United States. To accomplish this mission, NDAA serves as a nationwide, interdisciplinary resource center for training, research, technical assistance, and publications reflecting the highest standards and cutting-edge practices of the prosecutorial profession. In 1985, the National District Attorneys Association recognized the unique challenges of crimes involving child victims and established the National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse (NCPCA). NCPCA’s mission is to reduce the number of children victimized and exploited by assisting prosecutors and allied professionals laboring on behalf of victims too small, scared or weak to protect themselves. Suzanna Tiapula Director, National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse A program of the National District Attorneys Association www.ndaa.org 703.549.9222 This project was supported by Grants #2010-CI-FX-K008 and [new VOCA grant #] awarded by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention is a component of the Office of Justice Programs. Points of view in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Reserve Component Personnel Issues: Questions and Answers

Reserve Component Personnel Issues: Questions and Answers Updated June 15, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL30802 Reserve Component Personnel Issues: Questions and Answers Summary The Constitution provides Congress with broad powers over the Armed Forces, including the power to “to raise and support Armies,” “to provide and maintain a Navy,” “to make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces” and “to provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States.” In the exercise of this constitutional authority, Congress has historically shown great interest in various issues that bear on the vitality of the reserve components, such as funding, equipment, and personnel policy. This report is designed to provide an overview of key reserve component personnel issues. The term “Reserve Component” refers collectively to the seven individual reserve components of the Armed Forces: the Army National Guard of the United States, the Army Reserve, the Navy Reserve, the Marine Corps Reserve, the Air National Guard of the United States, the Air Force Reserve, and the Coast Guard Reserve. The purpose of these seven reserve components, as codified in law at 10 U.S.C. §10102, is to “provide trained units and qualified persons available for active duty in the armed forces, in time of war or national emergency, and at such other times as the national security may require, to fill the needs of the armed forces whenever more units and persons are needed than are in the regular components.” During the Cold War era, the reserve components were a manpower pool that was rarely used. -

Senate Committee on Transportation and Homeland Security Interim Report to the 80Th Legislature

SENATE COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION AND HOMELAND SECURITY REPORT TO THE 80TH LEGISLATURE DECEMBER 2006 S ENATE C OMMITTEE ON T RANSPORTATION AND H OMELAND S ECURITY January 2, 2007 The Honorable David Dewhurst Lieutenant Governor P.O. Box 12068 Austin, Texas 78711 Dear Governor Dewhurst: The Senate Committee on Transportation and Homeland Security is pleased to submit its final report, which considers the Committee's seven interim charges and three joint charges to study and report on: · the state's overweight truck fees; · federal actions regarding the Patriot Act on homeland security activities in Texas; · the implementation of SB 9, 79th Legislature, Regular Session; · TxDOT's ability to build, maintain, and relocate rail facilities; · naming of state highways; · TxDOT's programs to increase safety on all state transportation facilities; · monitor federal, state and local efforts along the Texas Mexico border; · relocation of utilities from state owned right-of-way; · process of allocation by the TxDOT Commission through the Allocation Program; · process by which federal funding sources should be implemented by the TxDOT Commission to comply with funding reductions mandated by Congress. Respectfully submitted, Senator John Carona Senator Gonzalo Barrientos Senator Ken Armbrister Chairman Vice-Chairman Senator Kim Brimer Senator Rodney Ellis Senator Florence Shapiro Senator Eliot Shapleigh Senator Jeff Wentworth Senator Tommy Williams P.O. BOX 12068 • SAM HOUSTON BUILDING, ROOM 445 • AUSTIN, TEXAS 78711 512/463-0067 • FAX 512/463-2840 • DIAL 711 FOR RELAY CALLS HTTP://WWW.SENATE.STATE.TX.US/75R/SENATE/COMMIT/C640/C640.HTM Table of Contents Interim Charges............................................................................................................................... 1 Charge 1 -- Overweight Truck Fee Structure................................................................................. -

Long-Term Outcome of Abusive Head Trauma

Pediatr Radiol (2014) 44 (Suppl 4):S548–S558 DOI 10.1007/s00247-014-3169-8 SPECIAL ISSUE: ABUSIVE HEAD TRAUMA Long-term outcome of abusive head trauma Mathilde P. Chevignard & Katia Lind Received: 23 January 2014 /Revised: 22 May 2014 /Accepted: 20 August 2014 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 Abstract Abusive head trauma is a severe inflicted traumatic include demographic factors (lower parental socioeconomic brain injury, occurring under the age of 2 years, defined by an status), initial severe presentation (e.g., presence of a coma, acute brain injury (mostly subdural or subarachnoidal haem- seizures, extent of retinal hemorrhages, presence of an asso- orrhage), where no history or no compatible history with the ciated cranial fracture, extent of brain lesions, cerebral oedema clinical presentation is given. The mortality rate is estimated at and atrophy). Given the high risk of severe outcome, long- 20-25% and outcome is extremely poor. High rates of impair- term comprehensive follow-up should be systematically per- ments are reported in a number of domains, such as delayed formed to monitor development, detect any problem and psychomotor development; motor deficits (spastic hemiplegia implement timely adequate rehabilitation interventions, spe- or quadriplegia in 15–64%); epilepsy, often intractable (11– cial education and/or support when necessary. Interventions 32%); microcephaly with corticosubcortical atrophy (61– should focus on children as well as families, providing help in 100%); visual impairment (18–48%); language disorders dealing with the child’s impairment and support with psycho- (37–64%), and cognitive, behavioral and sleep disorders, in- social issues. Unfortunately, follow-up of children with abu- cluding intellectual deficits, agitation, aggression, tantrums, sive head trauma has repeatedly been reported to be challeng- attention deficits, memory, inhibition or initiation deficits (23– ing, with very high attrition rates. -

Injury Patterns Associated with Shaken Baby Syndrome

KEANE LAW FIRM Injuries associated with Shaken Baby Syndrome Please call the Keane Law Firm to assist you with your injured child’s case (415) 398-2777 www.keanelaw.com Descriptors of specific head injury patterns often associated with SBS or non-accidental head trauma Non-accidental traumatic brain injury (Shaken Baby Syndrome) results in bleeding inside the skull. There are different types of tissue that hemorrhage or bleed inside the brain and cranium. The clinical presentation of the injured child is dependant on and determined by the part of the child’s brain or area(s) of lining that is/are bleeding; such as epidural hematomas or hemorrhage, subdural hematomas and intracerebral hematomas that may be present. The location of bleeding determines the type of symptoms a child may experience. Epidural hematomas and bleeding are most likely related to arterial bleeds and may lead to the rapid demise of a child’s condition if not surgically corrected in a timely manner. The hemorrhaging causes the child’s brain to shift or may cause herniation of the child’s brain and brainstem through the foramen magnum at the bottom of the skull. Both conditions, if allowed to persist and progress, may cause death. Epidural and subdural hematomas are often times are associated with skull fractures. Subdural hematomas may be acute (< 48 hours) or chronic (> 48 hours to 2 weeks). The subdural bleeding originates from the meningeal and cerebral venous network. The blood may accumulate rapidly or slowly depending on the pathology of the injury and child’s co-morbidities. Subdural hematomas may or may not result in brain shift and/or brainstem herniation. -

Amicus Brief

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS ESSEX, MIDDLESEX SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT NOS. SJC-11921, 11928 COMMONWEALTH V. DERICK EPPS AND OSWELT MILLIEN, APPELLANTS ______________________________________ APPEAL FROM JUDGMENTS OF THE ESSEX AND MIDDLESEX SUPERIOR COURTS ______________________________________ BRIEF AND APPENDIX OF CPCS, ACLUM, AND MACDL AS AMICI CURIAE ______________________________________ For ACLUM For CPCS Matthew R. Segal Dennis Shedd BBO #654489 BBO #555475 ACLU Foundation of MA 114 Waltham Street, Suite 14 211 Congress Street Lexington, MA 02421 Boston, MA 02110 (781) 274-7709 (617) 482-3170 [email protected] [email protected] For MACDL Chauncey B. Wood BBO #600354 Wood & Nathanson, LLP 227 Lewis Wharf Boston, MA 02110 (617) 248-1806 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Authorities . iii Issues Presented . 1 Statements of Interest of the Amici Curiae . 1 Summary of the Argument . 3 Argument . 5 I. The Scientific Understanding of the Causes of Infant Head Injury Has Evolved Over the Last 45 Years. 5 A. The Origins of the Shaken Baby Syndrome Theory . 5 B. Challenges to the Shaken Baby Syndrome Theory . 10 C. Reacting to the Challenges . 20 D. Recent Survey Articles in Law Journals Have Brought These Issues to Wider Attention in the Legal Community. 24 II. The Opinions of the Experts in These Cases Have Evolved and Been Challenged Over the Years. 24 A. The Expert Evidence in These Cases . 24 B. In the Last Decade There Have Been Cases in Which the Children’s Hospital Experts’ Opinions Have Been Deemed Insufficient to Prove That Injuries Were Caused by Shaking. 31 III. Cases Alleging Shaken Baby Syndrome or Abusive Head Trauma May Give Rise to Well- Founded Claims of Ineffective Assistance of Counsel or Newly Discovered Evidence. -

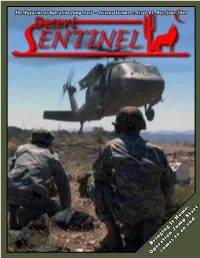

Bringing It Home: Op Eration Jum P Start Comes to an End

The Magazine of Operation Jump Start ~ Arizona Volume 2: Issue 03, May/June 2008 Bringing It Home: Operation Jump Start comes to an end. Volume 2: Issue 3 -May/June 2008 A desert sentinel is a “guardian of the desert.” This magazine tells the story of our Desert Sentinels, standing watch over the border and those who support Operation Jump Start - Arizona Desert Sentinel is an authorized publication for members of the Department of Defense. Contents of Desert Sentinel are not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, the Departments of the Army and/or Air Force, or the Adjutant General of Arizona. Desert Sentinel is published under the supervision of the Operation Jump Start – Arizona, Public Affairs Office, 5636 E. McDowell Road, Phoenix, AZ 85008-3495. To submit articles, photos and content, please email: [email protected] OPERATION JUMP START - ARIZONA Chain of Command Gov. Janet Napolitano FEATURES Commander in Cheif Army Maj. Gen. David Rataczak Raven and Diamondback work together improving state infrastructure.....4 Arizona Adjutant General Medicine is her life, her passion .............................................................................10 Army Col. Robert Centner JTF-Arizona Commander One of the final engineer rotations leaves their mark on OJS...........................12 Air Force Col. Wanda Wright JTF-Arizona Deputy Commander - Air A reluctant hero.........................................................................................................16 Army Col. Don Hoffmeister