Can Minorities Speak in Brendan Behan's the Hostage?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John F. Morrison Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 'THE AFFIRMATION OF BEHAN?' AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE POLITICISATION PROCESS OF THE PROVISIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT THROUGH AN ORGANISATIONAL ANALYSIS OF SPLITS FROM 1969 TO 1997 John F. Morrison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3158 This item is protected by original copyright ‘The Affirmation of Behan?’ An Understanding of the Politicisation Process of the Provisional Irish Republican Movement Through an Organisational Analysis of Splits from 1969 to 1997. John F. Morrison School of International Relations Ph.D. 2010 SUBMISSION OF PHD AND MPHIL THESES REQUIRED DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, John F. Morrison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in May, 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2010. Date 25-Aug-10 Signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

Irish History Links

Irish History topics pulled together by Dan Callaghan NC AOH Historian in 2014 Athenry Castle; http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/travel/attractions/castles/Galway/athenry.shtm Brehon Laws of Ireland; http://www.libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php February 1, in ancient Celtic times, it was the beginning of Spring and later became the feast day for St. Bridget; http://www.chalicecentre.net/imbolc.htm May 1, Begins the Celtic celebration of Beltane, May Day; http://wicca.com/celtic/akasha/beltane.htm. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ February 14, 269, St. Valentine, buried in Dublin; http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/valentine.htm March 17, 461, St. Patrick dies, many different reports as to the actual date exist; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm Dec. 7, 521, St. Columcille is born, http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_columcille_columba.htm January 23, 540 A.D., St. Ciarán, started Clonmacnoise Monastery; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04065a.htm May 16, 578, Feast Day of St. Brendan; http://parish.saintbrendan.org/church/story.php June 9th, 597, St. Columcille, dies at Iona; http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Columcille.html Nov. 23, 615, Irish born St. Columbanus dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/04137a.htm July 8, 689, St. Killian is put to death; http://allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/killian.html October 13, 1012, Irish Monk and Bishop St. Colman dies; http://www.stcolman.com/ Nov. 14, 1180, first Irish born Bishop of Dublin, St. Laurence O'Toole, dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091b.htm June 7, 1584, Arch Bishop Dermot O'Hurley is hung by the British for being Catholic; http://www.exclassics.com/foxe/dermot.htm 1600 Sept. -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

Gaelic Names of Plants

[DA 1] <eng> GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS [DA 2] “I study to bring forth some acceptable work: not striving to shew any rare invention that passeth a man’s capacity, but to utter and receive matter of some moment known and talked of long ago, yet over long hath been buried, and, as it seemed, lain dead, for any fruit it hath shewed in the memory of man.”—Churchward, 1588. [DA 3] GAELIC NAMES OE PLANTS (SCOTTISH AND IRISH) COLLECTED AND ARRANGED IN SCIENTIFIC ORDER, WITH NOTES ON THEIR ETYMOLOGY, THEIR USES, PLANT SUPERSTITIONS, ETC., AMONG THE CELTS, WITH COPIOUS GAELIC, ENGLISH, AND SCIENTIFIC INDICES BY JOHN CAMERON SUNDERLAND “WHAT’S IN A NAME? THAT WHICH WE CALL A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME WOULD SMELL AS SWEET.” —Shakespeare. WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCLXXXIII All Rights reserved [DA 4] [Blank] [DA 5] TO J. BUCHANAN WHITE, M.D., F.L.S. WHOSE LIFE HAS BEEN DEVOTED TO NATURAL SCIENCE, AT WHOSE SUGGESTION THIS COLLECTION OF GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS WAS UNDERTAKEN, This Work IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. [DA 6] [Blank] [DA 7] PREFACE. THE Gaelic Names of Plants, reprinted from a series of articles in the ‘Scottish Naturalist,’ which have appeared during the last four years, are published at the request of many who wish to have them in a more convenient form. There might, perhaps, be grounds for hesitation in obtruding on the public a work of this description, which can only be of use to comparatively few; but the fact that no book exists containing a complete catalogue of Gaelic names of plants is at least some excuse for their publication in this separate form. -

Book Auction Catalogue

1. 4 Postal Guide Books Incl. Ainmneacha Gaeilge Na Mbail Le Poist 2. The Scallop (Studies Of A Shell And Its Influence On Humankind) + A Shell Book 3. 2 Irish Lace Journals, Embroidery Design Book + A Lace Sampler 4. Box Of Pamphlets + Brochures 5. Lot Travel + Other Interest 6. 4 Old Photograph Albums 7. Taylor: The Origin Of The Aryans + Wilson: English Apprenticeship 1603-1763 8. 2 Scrap Albums 1912 And Recipies 9. Victorian Wildflowers Photograph Album + Another 10. 2 Photography Books 1902 + 1903 11. Wild Wealth – Sears, Becker, Poetker + Forbeg 12. 3 Illustrated London News – Cornation 1937, Silver Jubilee 1910-1935, Her Magesty’s Glorious Jubilee 1897 13. 3 Meath Football Champions Posters 14. Box Of Books – History Of The Times etc 15. Box Of Books Incl. 3 Vols Wycliff’s Opinion By Vaughan 16. Box Books Incl. 2 Vols Augustus John Michael Holroyd 17. Works Of Canon Sheehan In Uniform Binding – 9 Vols 18. Brendan Behan – Moving Out 1967 1st Ed. + 3 Other Behan Items 19. Thomas Rowlandson – The English Dance Of Death 1903. 2 Vols. Colour Plates 20. W.B. Yeats. Sophocle’s King Oedipis 1925 1st Edition, Yeats – The Celtic Twilight 1912 And Yeats Introduction To Gitanjali 21. Flann O’Brien – The Best Of Myles 1968 1st Ed. The Hard Life 1973 And An Illustrated Biography 1987 (3) 22. Ancient Laws Of Ireland – Senchus Mor. 1865/1879. 4 Vols With Coloured Lithographs 23. Lot Of Books Incl. London Museum Medieval Catalogue 24. Lot Of Irish Literature Incl. Irish Literature And Drama. Stephen Gwynn A Literary History Of Ireland, Douglas Hyde etc 25. -

Scottish Place-Name News No. 24

No. 24 Spring 2008 The Newsletter of the SCOTTISH PLACE-NAME SOCIETY COMANN AINMEAN-ÀITE NA H-ALBA In the hills north-west of Moffatdale, Dumfriesshire (photo by Pete Drummond). The small cairn is on Arthur’s Seat, a ridge of Hart Fell, whose broad top is to the left of this view over the smooth south-west flank of Swatte Fell to cliffs on White Coomb and, to their right, the twin tops of the transparently named Saddle Yoke. The instances of fell are within the Dumfriesshire and Galloway territory of this element, with few outliers farther north or east, as discussed inside in an article on ‘Gaelic and Scots in Southern Hill Names’. White Coomb may be named after the snow-bearing qualities of a coomb or ‘hollow in a mountain-side’ in its south-east face. Hart Fell and White Coomb are the same on William Crawford’s Dumfriesshire map of 1804, but Saddle Yoke is Saddleback and Swatte Fell is Swaw Fell, making it more doubtful that Swatte represents swart, referring to the long stretch of very dark cliffs on the far side. The postal address of the Scottish Place- names, and from whom the names reached Name Society is: written record in a far away place; the events c/o Celtic and Scottish Studies, University of occurred little over four centuries ago; and we Edinburgh, 27 George Square, Edinburgh could, with a little research, gain a good idea of EH8 9LD what kind of sounds would have been represented by the names as spelled in – Membership Details: Annual membership £6 presumably – a 16th century south Slavic dialect (£7 for overseas members because of higher of the Adriatic coast; a hasty online search gives postage costs), to be sent to Peter Drummond, no indication that a Croat of today would find it Apt 8 Gartsherrie Academy, Academy Place, particularly difficult to transliterate those Gaelic Coatbridge ML5 3AX. -

The Celtic Who's Wh

/ -^ H./n, bz ^^.c ' ^^ Jao ft « V o -i " EX-LlBRlS HEW- MORRISON M D E The Celtic Who's Wh. THE CELTIC WHO'S WHO Names and Addresses of Workers Who contribute to Celtic Literature, Music or other Cultural Activities Along with other Information KIRKCALDY, SCOTLAND: THE FIFESHIRE ADVERTISER LIMITED 1921 LAURISTON CASTLE LIBRARY ACCESSION CONTENTS Preface. ; PREFACE This compilation was first suggested by the needs nf the organisers of tlie Pau-Celtic Congjess held in Edin- burgh in May, 1920. Acting as convener ol the Scottish Committee for that event, the editor found that there was in existence no list of persons who took an acti^•p interest in such matters, either in Scotland or in any of the other Celtic countries. His resolve to meet this want was cordially approved by the lenxlers of tlie Congress circulars were issued to all wlrose addresses could be discovered, and these were invited to suggest the n-iines of others who ought to be included. The net result is not quite up to expectation, but it is better tlaan at first seemed probable. The Celt may not really be more shy or n.ore dilatory than men of other blood, but certainly the response to this elTort has not indicated on his pfirt any undue forwardness. Even now, after the lapse of a year and the issue of a second ;ind a third circular, tlie list of Celtic aaithors niid inu<;iciii::i.s is far from full. Perhaps a second edition of the l)"(>k, when called for, may be more complete. -

Babies' First Forenames: Births Registered in Scotland in 1997

Babies' first forenames: births registered in Scotland in 1997 Information about the basis of the list can be found via the 'Babies' First Names' page on the National Records of Scotland website. Boys Girls Position Name Number of babies Position Name Number of babies 1 Ryan 795 1 Emma 752 2 Andrew 761 2 Chloe 743 3 Jack 759 3 Rebecca 713 4 Ross 700 4 Megan 645 5 James 638 5 Lauren 631 6 Connor 590 6 Amy 623 7 Scott 586 7 Shannon 552 8 Lewis 568 8 Caitlin 550 9 David 560 9 Rachel 517 10 Michael 557 10 Hannah 480 11 Jordan 554 11 Sarah 471 12 Liam 550 12 Sophie 433 13 Daniel 546 13 Nicole 378 14 Cameron 526 14 Erin 362 15 Matthew 509 15 Laura 348 16 Kieran 474 16 Emily 289 17 Jamie 452 17 Jennifer 277 18 Christopher 440 18 Courtney 276 19 Kyle 421 19= Kirsty 258 20 Callum 419 19= Lucy 258 21 Craig 418 21 Danielle 257 22 John 396 22= Katie 252 23 Dylan 394 22= Louise 252 24 Sean 367 24 Heather 250 25 Thomas 348 25 Rachael 221 26 Adam 347 26 Eilidh 214 27 Calum 335 27 Holly 213 28 Mark 310 28 Samantha 208 29 Robert 297 29 Stephanie 202 30 Fraser 292 30= Kayleigh 194 31 Alexander 288 30= Zoe 194 32 Declan 284 32 Melissa 189 33 Paul 266 33 Claire 182 34 Aaron 260 34 Chelsea 180 35 Stuart 257 35 Jade 176 36 Euan 252 36 Robyn 173 37 Steven 243 37 Jessica 160 38 Darren 231 38= Aimee 159 39 William 228 38= Gemma 159 40 Lee 226 38= Nicola 159 41= Aidan 207 41 Hayley 156 41= Stephen 207 42= Lisa 155 43 Nathan 205 42= Natalie 155 44 Shaun 198 44 Anna 151 45 Ben 195 45 Natasha 148 46 Joshua 191 46 Charlotte 134 47 Conor 176 47 Abbie 132 48 Ewan 174 -

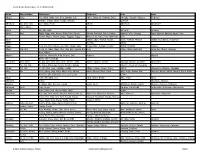

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

From the Political to the Personal:Interrogation, Imprisonment, and Sanction in the Prison Drama of Seamus Byrne and Brendan Behan Charles F

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 2014 From the Political to the Personal:Interrogation, Imprisonment, and Sanction In the Prison Drama of Seamus Byrne and Brendan Behan Charles F. French Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation French, Charles F., "From the Political to the Personal:Interrogation, Imprisonment, and Sanction In the Prison Drama of Seamus Byrne and Brendan Behan" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1487. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From the Political to the Personal: Interrogation, Imprisonment, and Sanction In the Prison Drama of Seamus Byrne and Brendan Behan. by Charles F. French A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Lehigh University May 2014 © 2014 Copyright Charles F. French ii Approved and recommended for acceptance as a dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Charles French From the Political to the Personal: Interrogation, Imprisonment, and Sanction In the Prison Drama of Seamus Byrne and Brendan Behan. Dissertation Director Professor Elizabeth Fifer Approved Date Committee Members: Professor Elizabeth Fifer Professor Ed Lotto Professor Amardeep Singh Professor Pam Pepper (Name of Committee Member) iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are several people to whom I must give my thanks for assistance and guidance in the writing of this project. -

Trotskyists Debate Ireland Workers’ Liberty Volume 3 No 45 October 2014 £1 Reason in Revolt Trotskyists Debate Ireland 1939, Mid-50S, 1969

Trotskyists debate Ireland Workers’ Liberty Volume 3 No 45 October 2014 £1 www.workersliberty.org Reason in revolt Trotskyists debate Ireland 1939, mid-50s, 1969 1 Workers’ Liberty Trotskyists debate Ireland Introduction: freeing Marxism from pseudo-Marxist legacy By Sean Matgamna “Since my early days I have got, through Marx and Engels, Slavic peoples; the annihilation of Jews, gypsies, and god the greatest sympathy and esteem for the heroic struggle of knows who else. the Irish for their independence” — Leon Trotsky, letter to If nonetheless Irish nationalists, Irish “anti-imperialists”, Contents Nora Connolly, 6 June 1936 could ignore the especially depraved and demented charac - ter of England’s imperialist enemy, and wanted it to prevail In 1940, after the American Trotskyists split, the Shachtman on the calculation that Catholic Nationalist Ireland might group issued a ringing declaration in support of the idea of gain, that was nationalism (the nationalism of a very small 2. Introduction: freeing Marxism from a “Third Camp” — the camp of the politically independent part of the people of Europe), erected into absolute chauvin - revolutionary working class and of genuine national liberation ism taken to the level of political dementia. pseudo-Marxist legacy, by Sean Matgamna movements against imperialism. And, of course, the IRA leaders who entered into agree - “What does the Third Camp mean?”, it asked, and it ment with Hitler represented only a very small segment of 5. 1948: Irish Trotskyists call for a united replied: Irish opinion, even of generally anti-British Irish opinion. “It means Czech students fighting the Gestapo in the The presumption of the IRA, which literally saw itself as Ireland with autonomy for the Protestant streets of Prague and dying before Nazi rifles in the class - the legitimate government of Ireland, to pursue its own for - rooms, with revolutionary slogans on their lips. -

Abbey Theatre, 443, 544; Rioting At, 350 Abbot, Charles, Irish Chief Secretary, 240 Abercorn Restaurant, Belfast, Bomb In, 514 A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19720-5 - Ireland: A History Thomas Bartlett Index More information INDEX Abbey Theatre, 443, 544; rioting at, 350 247, 248; and Whiteboys, 179, 199, Abbot, Charles, Irish chief secretary, 240 201, 270 Abercorn restaurant, Belfast, bomb in, 514 Ahern, Bertie, Taoiseach, 551, 565;and Aberdeen, Ishbel, Lady, 8 Tony Blair, 574; investigated, 551;and abortion, in early Ireland, 7; in modern peace process talks (1998), 566 Ireland, banned, 428, 530–1; Aidan, Irish missionary, 26 referendum on, 530; see ‘X’case AIDS crisis see under contraception ActofAdventurers(1642), 129 Aiken, Frank, 419, 509; minister of defence, ActofExplanation(1665), 134 440; wartime censorship, 462 Act to prevent the further growth of popery aislingı´ poetry, 169 (1704), 163, 167, 183 Al Qaeda, attacks in United States, 573 Act of Satisfaction (1653), 129 Albert, cardinal archduke, 97 ActofSettlement(1652), 129 alcohol: attitudes towards in Ireland and ActofSettlement(1662), 133 Britain, nineteenth century, 310; Adams, Gerry, republican leader, 511, consumption of during ‘Celtic Tiger’, 559–60, 565; and the IRA, 522;and 549; and see whiskey power-sharing, 480–1; and strength of Alen, Archbishop John, death of, 76 his position, 569; and study of Irish Alen, John, clerk of council, 76 history, 569; and talks with John Hume, Alexandra College, Dublin, 355 559, 561; and David Trimble, 569;and Alfred, king, 26 visa to the United States, 562; wins Algeria, 401 parliamentary seat in West Belfast, Allen, William, Manchester Martyr, 302 526