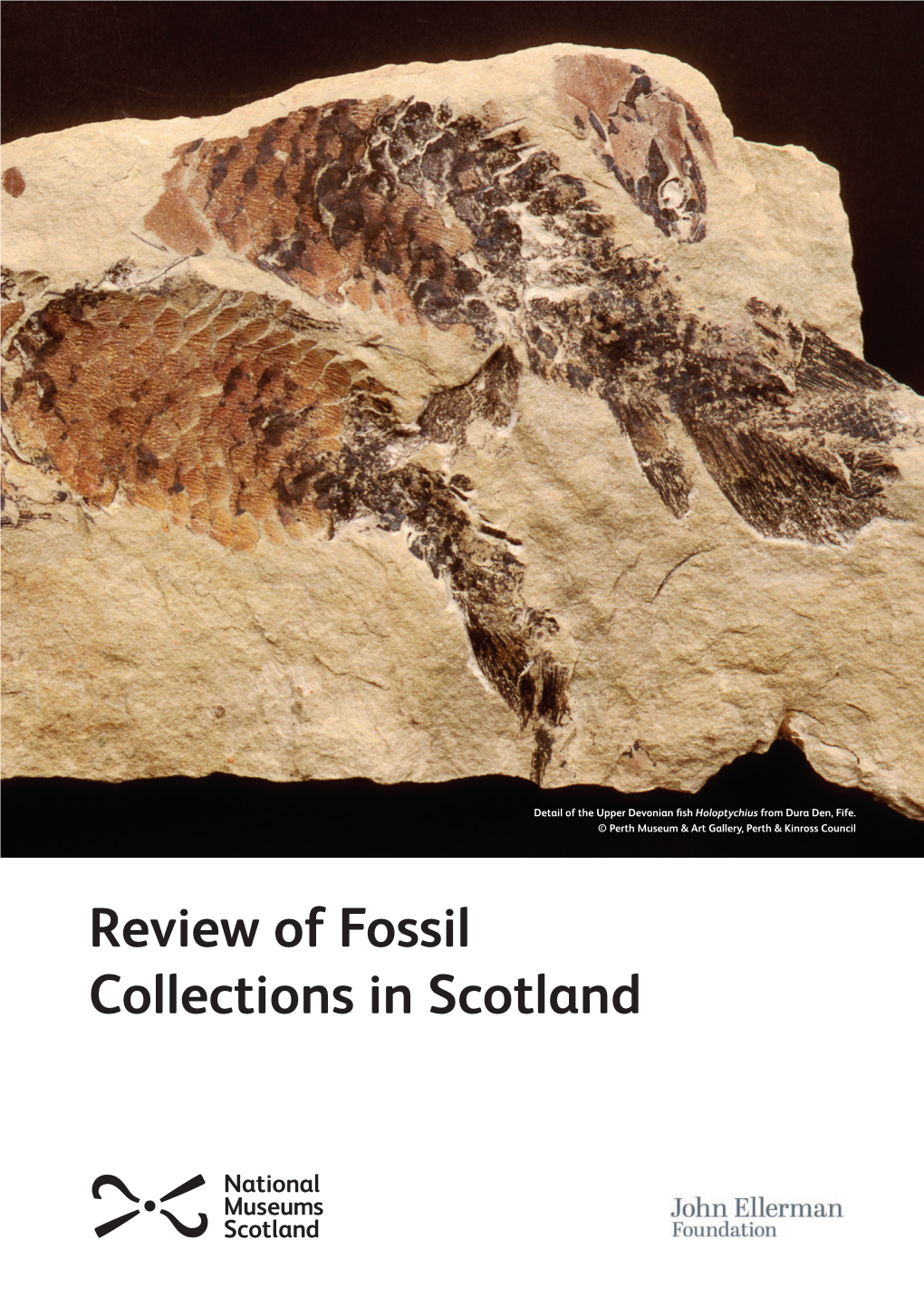

Review of Fossil Collections in Scotland Review of Fossil Collections in Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEMBROKESHIRE © Lonelyplanetpublications Biggest Megalithicmonumentinwales

© Lonely Planet Publications 162 lonelyplanet.com PEMBROKESHIRE COAST NATIONAL PARK •• Information 163 porpoises and whales are frequently spotted PEMBROKESHIRE COAST in coastal waters. Pembrokeshire The park is also a focus for activities, from NATIONAL PARK hiking and bird-watching to high-adrenaline sports such as surfing, coasteering, sea kayak- The Pembrokeshire Coast National Park (Parc ing and rock climbing. Cenedlaethol Arfordir Sir Benfro), established in 1952, takes in almost the entire coast of INFORMATION Like a little corner of California transplanted to Wales, Pembrokeshire is where the west Pembrokeshire and its offshore islands, as There are three national park visitor centres – meets the sea in a welter of surf and golden sand, a scenic extravaganza of spectacular sea well as the moorland hills of Mynydd Preseli in Tenby, St David’s and Newport – and a cliffs, seal-haunted islands and beautiful beaches. in the north. Its many attractions include a dozen tourist offices scattered across Pembro- scenic coastline of rugged cliffs with fantas- keshire. Pick up a copy of Coast to Coast (on- Among the top-three sunniest places in the UK, this wave-lashed western promontory is tically folded rock formations interspersed line at www.visitpembrokeshirecoast.com), one of the most popular holiday destinations in the country. Traditional bucket-and-spade with some of the best beaches in Wales, and the park’s free annual newspaper, which has seaside resorts like Tenby and Broad Haven alternate with picturesque harbour villages a profusion of wildlife – Pembrokeshire’s lots of information on park attractions, a cal- sea cliffs and islands support huge breeding endar of events and details of park-organised such as Solva and Porthgain, interspersed with long stretches of remote, roadless coastline populations of sea birds, while seals, dolphins, activities, including guided walks, themed frequented only by walkers and wildlife. -

Post-Carboniferous Stratigraphy, Northeastern Alaska by R

Post-Carboniferous Stratigraphy, Northeastern Alaska By R. L. DETTERMAN, H. N. REISER, W. P. BROSGE,and]. T. DUTRO,JR. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 886 Sedirnentary rocks of Permian to Quaternary age are named, described, and correlated with standard stratigraphic sequences UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1975 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Detterman, Robert L. Post-Carboniferous stratigraphy, northeastern Alaska. (Geological Survey Professional Paper 886) Bibliography: p. 45-46. Supt. of Docs. No.: I 19.16:886 1. Geology-Alaska. I. Detterman, Robert L. II. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Professional Paper 886. QE84.N74P67 551.7'6'09798 74-28084 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-02687-2 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract __ _ _ _ _ __ __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ __ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ __ _ _ __ __ __ _ _ _ _ __ 1 Stratigraphy__:_Continued Introduction __________ ----------____ ----------------____ __ 1 Kingak Shale ---------------------------------------- 18 Purpose and scope ----------------------~------------- 1 Ignek Formation (abandoned) -------------------------- 20 Geographic setting ------------------------------------ 1 Okpikruak Formation (geographically restricted) ________ 21 Previous work and acknowledgments ------------------ 1 Kongakut Formation ---------------------------------- -

University of Michigan University Library

CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THE MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN VOL. XI NO.6, pp. 101-157 (12 pk., 1 map) MARCH25, 1953 TRILOBITES OF THE DEVONIAN TRAVERSE GROUP OF MICHIGAN BY ERWIN C. STUMM UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS ANN ARBOR CONTMBUTIONS FROM THE MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY Director: LEWIS B. KELLUM The series of contributions from the Museum of Paleontology is a medium for the publication of papers based chiefly upon the collections in the Museum. When the number of pages issued is sufficient to make a volume, a title page and a table of contents will be sent to libraries on the mailing list, and also to individuals upon request. Correspondence should be directed to the University of Michigan Press. A list of the separate papers in Volumes II-IX will be sent upon request. VOL. I. The Stratigraphy and Fauna of the Hackberry Stage of the Upper Devonian, by C. L. Fenton and M. A. Fenton. Pages xi+260. Cloth. $2.75. VOL. 11. Fourteen papers. Pages ix+240. Cloth. $3.00. Parts sold separately in paper covers. VOL. 111. Thirteen papers. Pages viii+275. Cloth. $3.50. Parts sold separately in paper covers. VOL. IV. Eighteen papers. Pages viiif295. Cloth. $3.50. Parts sold separately in paper covers, VOL. V. Twelve papers. Pages viii+318. Cloth. $3.50. Parts sold separately in paper covers. VOL. VI. Ten papers. Pages vii+336. Paper covers. $3.00. Parts sold separately. VOLS. VII-IX. Ten numbers each, sold separately. (Continued on inside back cover) VOL. -

Sedimentology, Taphonomy, and Palaeoecology of a Laminated

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 243 (2007) 92–117 www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Sedimentology, taphonomy, and palaeoecology of a laminated plattenkalk from the Kimmeridgian of the northern Franconian Alb (southern Germany) ⁎ Franz Theodor Fürsich a, , Winfried Werner b, Simon Schneider b, Matthias Mäuser c a Institut für Paläontologie, Universität Würzburg, Pleicherwall 1, 97070 Würzburg, Germany LMU b Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie and GeoBio-Center , Richard-Wagner-Str. 10, D-80333 München, Germany c Naturkunde-Museum Bamberg, Fleischstr. 2, D-96047 Bamberg, Germany Received 8 February 2006; received in revised form 3 July 2006; accepted 7 July 2006 Abstract At Wattendorf in the northern Franconian Alb, southern Germany, centimetre- to decimetre-thick packages of finely laminated limestones (plattenkalk) occur intercalated between well bedded graded grainstones and rudstones that blanket a relief produced by now dolomitized microbialite-sponge reefs. These beds reach their greatest thickness in depressions between topographic highs and thin towards, and finally disappear on, the crests. The early Late Kimmeridgian graded packstone–bindstone alternations represent the earliest plattenkalk occurrence in southern Germany. The undisturbed lamination of the sediment strongly points to oxygen-free conditions on the seafloor and within the sediment, inimical to higher forms of life. The plattenkalk contains a diverse biota of benthic and nektonic organisms. Excavation of a 13 cm thick plattenkalk unit across an area of 80 m2 produced 3500 fossils, which, with the exception of the bivalve Aulacomyella, exhibit a random stratigraphic distribution. Two-thirds of the individuals had a benthic mode of life attached to hard substrate. This seems to contradict the evidence of oxygen-free conditions on the sea floor, such as undisturbed lamination, presence of articulated skeletons, and preservation of soft parts. -

ALBIAN AMMONITES of POLAND (Plates 1—25)

PALAEONTOLOGIA POLQNICA mm ■'Ъ-Ь POL T S H ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF PALEOBIOLOGY PALAEONTOLOGIA POLONICA—No. 50, 1990 t h e a l b ia w AMMONITES OF POLAND (AMQNITY ALBU POLS К I) BY RYSZARD MARCINOWSKI AND JOST WIEDMANN (WITH 27 TEXT-FIGURES, 7 TABLES AND 25 PLATES) WARSZAWA —KRAKÔW 1990 PANSTWOWE WYDAWNICTWO NAUKOWE KEDAKTOR — EDITOR JOZEP KA2MIERCZAK 2ASTEPCA HEDAKTOHA _ ASSISTANT EDITOR m AôDAlenA BÛRSUK-BIALYNICKA Adres Redakcjl — Address of the Editorial Office Zaklad Paleobiologij Polska Akademia Nauk 02-089 Warszawa, AI. 2w irki i Wigury 93 KOREKTA Zespol © Copyright by Panstwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe Warszawa — Krakôw 1990 ISBN 83-01-09176-2 ISSN 0078-8562 Panstwowe Wydawnielwo Naukowe — Oddzial w Krakowie Wydanie 1, Naklad 670 + 65 cgz. Ark. wyd. 15. Ark. druk. 6 + 25 wkladek + 5 wklejek. Papier offset, sat. Ill kl. 120 g. Oddano do skiadania w sierpniu 1988 r. Podpisano do druku w pazdzierniku 1990 r. Druk ukoriczono w listopadzie 1990 r. Zara. 475/87 Drukarnia Uniwersytetu Jagielloriskiego w Krakowie In Memory of Professor Edward Passendorfer (1894— 1984) RYSZARD MARCINOWSKI and JOST WIEDMANN THE ALBIAN AMMONITES OF POLAND (Plates 1—25) MARCINOWSKI, R. and WIEDMANN, J.: The Albian ammonites of Poland. Palaeonlologia Polonica, 50, 3—94, 1990. Taxonomic and ecological analysis of the ammonite assemblages, as well as their general paleogeographical setting, indicate that the Albian deposits in the Polish part of the Central European Basin accumulated under shallow or extremely shallow marine conditions, while those of the High-Tatra Swell were deposited in an open sea environment. The Boreal character of the ammonite faunas in the epicontinental area of Poland and the Tethyan character of those in the Tatra Mountains are evident in the composition of the analyzed assemblages. -

Wales: River Wye to the Great Orme, Including Anglesey

A MACRO REVIEW OF THE COASTLINE OF ENGLAND AND WALES Volume 7. Wales. River Wye to the Great Orme, including Anglesey J Welsby and J M Motyka Report SR 206 April 1989 Registered Office: Hydraulics Research Limited, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX1 0 8BA. Telephone: 0491 35381. Telex: 848552 ABSTRACT This report reviews the coastline of south, west and northwest Wales. In it is a description of natural and man made processes which affect the behaviour of this part of the United Kingdom. It includes a summary of the coastal defences, areas of significant change and a number of aspects of beach development. There is also a brief chapter on winds, waves and tidal action, with extensive references being given in the Bibliography. This is the seventh report of a series being carried out for the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. For further information please contact Mr J M Motyka of the Coastal Processes Section, Maritime Engineering Department, Hydraulics Research Limited. Welsby J and Motyka J M. A Macro review of the coastline of England and Wales. Volume 7. River Wye to the Great Orme, including Anglesey. Hydraulics Research Ltd, Report SR 206, April 1989. CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 COASTAL GEOLOGY AND TOPOGRAPHY 3.1 Geological background 3.2 Coastal processes 4 WINDS, WAVES AND TIDAL CURRENTS 4.1 Wind and wave climate 4.2 Tides and tidal currents 5 REVIEW OF THE COASTAL DEFENCES 5.1 The South coast 5.1.1 The Wye to Lavernock Point 5.1.2 Lavernock Point to Porthcawl 5.1.3 Swansea Bay 5.1.4 Mumbles Head to Worms Head 5.1.5 Carmarthen Bay 5.1.6 St Govan's Head to Milford Haven 5.2 The West coast 5.2.1 Milford Haven to Skomer Island 5.2.2 St Bride's Bay 5.2.3 St David's Head to Aberdyfi 5.2.4 Aberdyfi to Aberdaron 5.2.5 Aberdaron to Menai Bridge 5.3 The Isle of Anglesey and Conwy Bay 5.3.1 The Menai Bridge to Carmel Head 5.3.2 Carmel Head to Puffin Island 5.3.3 Conwy Bay 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 REFERENCES BIBLIOGRAPHY FIGURES 1. -

North-East & Mid Pembrokeshire

Poppit B B 4 4 5 5 4 4 6 8 BAE CARDIGAN Llandudoch Aberteifi CARDIGAN BAY Ceibwr Bay St Dogmaels Cardigan North-East & Trewyddel Moylegrove Pen Caer Cilgerran Mid PembroStrumbkle Heaed shire Dinas Head 82 Newport 45 aNanhyfer iB l Srands Nevern T Castell 2 Wdig B433 Goodwick Dinas 2 Henllys Pwll Deri 1 Felindre Eglwyswrw Farchog B4 Boncath Abergwaun Trefdraeth 332 Fishguard 4 Newport Crosswell St Nicholas CWM GWAUN 3 Abermawr Llanychaer GWAUN VALLEY 9 Brynberian 2 3 4 5 Scleddau B Abercastle Pontfaen BRYNIAU PRESELI Llangloffan B Crymych 43 PRESELI HILLS Trefin 13 Porthgain Mathry Jordanston Abereiddy Casmorys B4331 Treletert Mynachlogddu Croesgoch Castlemorris New Inn Letterston W C e l s Cas-mael en Dewi e t 1111 d e Rosebush ds Head d rn Puncheston 6 a Tufton u B Caerfarchell rthmawr 4583 Cas-blaidd Maenclochog sands Bay Tyddewi Llandeloy Wolfscastle 12 u a Middle Mill B St D avids 4 d 3 9 3 Ambleston 2 d 0 43 e Solfach Hayscastle B New Moat l Efailwen 9 Solva C n r 8 e C t a s P e Treffgarne a o rf E rt ai Spittal Walton East hc la is Newgale Llandissilio wi Newgale Sands Roch land Camrose Clarbeston Road Keeston B 10 2211 43 Rickets Head Simpson 13 Clunderwen Cross Nolton Haven Wiston H lff dd Llawhaden Llandewi 01 . Llys Meddyg Restaurant with Rooms, Newport ................ 08 02. Morawelon Café, Bar & Restaurant, Newport .................... 08 why not 03. Bluesto ne Brewing, Newport .................................................... 09 04. The Gour met Pig, Fishguard .................................................... 09 stock up 05. -

Available Generic Names for Trilobites

AVAILABLE GENERIC NAMES FOR TRILOBITES P.A. JELL AND J.M. ADRAIN Jell, P.A. & Adrain, J.M. 30 8 2002: Available generic names for trilobites. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 48(2): 331-553. Brisbane. ISSN0079-8835. Aconsolidated list of available generic names introduced since the beginning of the binomial nomenclature system for trilobites is presented for the first time. Each entry is accompanied by the author and date of availability, by the name of the type species, by a lithostratigraphic or biostratigraphic and geographic reference for the type species, by a family assignment and by an age indication of the type species at the Period level (e.g. MCAM, LDEV). A second listing of these names is taxonomically arranged in families with the families listed alphabetically, higher level classification being outside the scope of this work. We also provide a list of names that have apparently been applied to trilobites but which remain nomina nuda within the ICZN definition. Peter A. Jell, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane, Queensland 4101, Australia; Jonathan M. Adrain, Department of Geoscience, 121 Trowbridge Hall, Univ- ersity of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242, USA; 1 August 2002. p Trilobites, generic names, checklist. Trilobite fossils attracted the attention of could find. This list was copied on an early spirit humans in different parts of the world from the stencil machine to some 20 or more trilobite very beginning, probably even prehistoric times. workers around the world, principally those who In the 1700s various European natural historians would author the 1959 Treatise edition. Weller began systematic study of living and fossil also drew on this compilation for his Presidential organisms including trilobites. -

Silurian Rugose Corals of the Central and Southwest Great Basin

Silurian Rugose Corals of the Central and Southwest Great Basin GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 777 Silurian Rugose Corals of the Central and Southwest Great Basin By CHARLES W. MERRIAM GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 777 A stratigraphic-paleontologic investigation of rugose corals as aids in age detern2ination and correlation of Silurian rocks of the Great Basin with those of other regions UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1973 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 73-600082 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402- Price $2.15 (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-00363 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract--------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Systematic and descriptive palaeontology-Continued Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Family Streptelasmatidae-Continued Purpose and scope of investigation------------------------------- 1 Dalmanophyllum ------------------------------------------------- 32 History of investigation ---------------------------------------------- 1 Family Stauriidae ------------------------------------------------------- 32 Methods of study------------------------------------------------------- 2 Cyathoph y llo ides-------------------------------------------------- 32 Acknowledgments------------------------------------------------------- 4 Palaeophyllum -

The Cretaceous of North Greenland

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Zitteliana - Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Histor. Geologie Jahr/Year: 1982 Band/Volume: 10 Autor(en)/Author(s): Birkelund Tove, Hakansson Eckhart Artikel/Article: The Cretaceous of North Greenland - a stratigraphic and biogeographical analysis 7-25 © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at 7 Zitteliana 10 7-25 München, 1. Juli 1983 ISSN 0373-9627 The Cretaceous of North Greenland - a stratigraphic and biogeographical analysis By TOVE BIRKELUND & ECKART HÄKANSSON*) With 6 text figures and 3 plates ABSTRACT Mapping of the Wandel Sea Basin (81-84°N) has revealed realites, Peregrinoceras, Neotollia, Polyptycbites, Astieripty- an unusually complete Late Jurassic to Cretaceous sequence chites) are Boreal and Sub-Boreal, related to forms primarily in the extreme Arctic. The Cretaceous pan of the sequence in known from circum-arctic regions (Sverdrup Basin, Svalbard, cludes marine Ryazanian, Valanginian, Aptian, Albian, Tu Northern and Western Siberia), but they also have affinities to ranian and Coniacian deposits, as well as outliers of marine occurrences as far south as Transcaspia. The Early Albian Santonian in a major fault zone (the Harder Fjord Fault Zone) contains a mixing of forms belonging to different faunal pro west of the main basin. Non-marine PHauterivian-Barremian vinces (e. g. Freboldiceras, Leymeriella, Arctboplites), linking and Late Cretaceous deposits are also present in addition to North Pacific, Atlantic, Boreal/Russian platform and Trans Late Cretaceous volcanics. caspian faunas nicely together. Endemic Turonian-Coniacian Scapbites faunas represent new forms related to European An integrated dinoflagellate-ammonite-5«c/;D stratigra species. -

Contents List of Illustrations LETTER OF

STATE OF MICHIGAN Plate IV. A. Horizontal and oblique lamination, Sylvania MICHIGAN GEOLOGICAL AND BIOLOGICAL SURVEY Sandstone......................................................................27 Plate IV. B. Stratification and lamination, in sand dune, Dune Publication 2. Geological Series 1. Park, Ind.........................................................................28 THE MONROE FORMATION OF SOUTHERN Plate V. Sand grains, enlarged 14½ times ............................31 MICHIGAN AND ADJOINING REGIONS Plate VI. Desert sand grains, enlarged 14½ times ................31 by Plate VII. Sylvania and St. Peter sand grains, enlarged 14½ A. W. Grabau and W. H. Sherzer times. .............................................................................32 PUBLISHED AS PART OF THE ANNUAL REPORT OF THE BOARD OF GEOLOGICAL AND BIOLOGICAL SURVEY FOR Figures 1909. Figure 1. Map showing distribution of Sylvania Sandstone. 25 LANSING, MICHIGAN WYNKOOP HALLENBECK CRAWFORD CO., STATE Figure 2. Cross bedding in Sylvania sandstone ....................27 PRINTERS Figure 3. Cross bedding on east wall of Toll’s Pit quarry ......28 1910 Figure 4. Cross bedding shown on south wall of Toll’s Pit quarry.............................................................................28 Contents Figure 5. Cross bedding on south wall of Toll’s Pit quarry in Sylvania sandstone. .......................................................28 Letter of Transmittal. ......................................................... 1 Figure 6. Cross bedding shown on south wall -

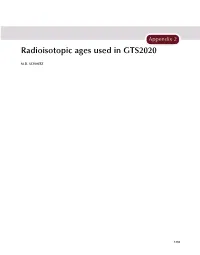

Schmitz, M. D. 2000. Appendix 2: Radioisotopic Ages Used In

Appendix 2 Radioisotopic ages used in GTS2020 M.D. SCHMITZ 1285 1286 Appendix 2 GTS GTS Sample Locality Lat-Long Lithostratigraphy Age 6 2s 6 2s Age Type 2020 2012 (Ma) analytical total ID ID Period Epoch Age Quaternary À not compiled Neogene À not compiled Pliocene Miocene Paleogene Oligocene Chattian Pg36 biotite-rich layer; PAC- Pieve d’Accinelli section, 43 35040.41vN, Scaglia Cinerea Fm, 42.3 m above base of 26.57 0.02 0.04 206Pb/238U B2 northeastern Apennines, Italy 12 29034.16vE section Rupelian Pg35 Pg20 biotite-rich layer; MCA- Monte Cagnero section (Chattian 43 38047.81vN, Scaglia Cinerea Fm, 145.8 m above base 31.41 0.03 0.04 206Pb/238U 145.8, equivalent to GSSP), northeastern Apennines, Italy 12 28003.83vE of section MCA/84-3 Pg34 biotite-rich layer; MCA- Monte Cagnero section (Chattian 43 38047.81vN, Scaglia Cinerea Fm, 142.8 m above base 31.72 0.02 0.04 206Pb/238U 142.8 GSSP), northeastern Apennines, Italy 12 28003.83vE of section Eocene Priabonian Pg33 Pg19 biotite-rich layer; MASS- Massignano (Oligocene GSSP), near 43.5328 N, Scaglia Cinerea Fm, 14.7 m above base of 34.50 0.04 0.05 206Pb/238U 14.7, equivalent to Ancona, northeastern Apennines, 13.6011 E section MAS/86-14.7 Italy Pg32 biotite-rich layer; MASS- Massignano (Oligocene GSSP), near 43.5328 N, Scaglia Cinerea Fm, 12.9 m above base of 34.68 0.04 0.06 206Pb/238U 12.9 Ancona, northeastern Apennines, 13.6011 E section Italy Pg31 Pg18 biotite-rich layer; MASS- Massignano (Oligocene GSSP), near 43.5328 N, Scaglia Cinerea Fm, 12.7 m above base of 34.72 0.02 0.04 206Pb/238U