Situated Politeness: Manipulating Honorific and Non-Honorific Expressions in Japanese Conversations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Happened to the Honorifics in a Local Japanese Dialect in 55 Years: a Report from the Okazaki Survey on Honorifics

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 18 Issue 2 Selected Papers from NWAV 40 Article 7 9-2012 What Happened to the Honorifics in a Local Japanese Dialect in 55 years: A Report from the Okazaki Survey on Honorifics Kenjiro Matsuda Kobe Shoin Women’s University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Matsuda, Kenjiro (2012) "What Happened to the Honorifics in a Local Japanese Dialect in 55 years: A Report from the Okazaki Survey on Honorifics," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 18 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol18/iss2/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol18/iss2/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. What Happened to the Honorifics in a Local Japanese Dialect in 55 ears:y A Report from the Okazaki Survey on Honorifics Abstract This paper reports the analysis of the three trend samples from the Okazaki Honorifics Survey, a longitudinal survey by the National Language Research Institute on the use and the awareness of honorifics in Okazaki city, Aichi Prefecture in Japan. Its main results are: (1) the Okazakians are using more polite forms over the 55 years; (2) the effect of the three social variables (sex, age, and educational background), which used to be strong factors controlling the use of the honorifics in the speech community, are diminishing over the years; (3) in OSH I and II, the questions show clustering by the feature [±service interaction], while the same 11 questions in OSH III exhibit clustering by a different feature, [±spontaneous]; (4) the change in (3) and (4) can be accounted for nicely by the Democratization Hypothesis proposed by Inoue (1999) for the variation and change of honorifics in other Japanese dialects. -

Modern JAPANESE Grammar

Modern JAPANESE Grammar Modern Japanese Grammar: A Practical Guide is an innovative reference guide to Japanese, combining traditional and function-based grammar in a single volume. The Grammar is divided into two parts. Part A covers traditional grammatical categories such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, particles, topics, honorifics, etc. Part B is carefully organized around language functions, covering all major communication situations such as: • Initiating and ending a conversation • Seeking and giving factual information • Expressing gratitude, likes and dislikes • Making requests and asking for permission and advice. With a strong emphasis on contemporary usage, all grammar points and functions are richly illustrated throughout with examples written both in romanization and Japanese script (a mixture of hiragana, katakana, and kanji). Main features of the Grammar include: • Clear, succinct and jargon-free explanations • Extensive cross-referencing between the different sections • Emphasis on areas of particular difficulty for learners of Japanese. Both as a reference grammar and a practical usage manual, Modern Japanese Grammar: A Practical Guide is the ideal resource for learners of Japanese at all levels, from beginner to advanced. No prior knowledge of grammatical terminology or Japanese script is required and a glossary of grammatical terms is provided. This Grammar is accompanied by the Modern Japanese Grammar Workbook (ISBN 978-0- 415-27093-9), which features related exercises and activities. Naomi H. McGloin is Professor of Japanese Language and Linguistics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. Mutsuko Endo Hudson is Professor of Japanese Language and Linguistics at Michigan State University, USA. Fumiko Nazikian is Senior Lecturer and Director of the Japanese Language Program at Columbia University, USA. -

Berkeley Linguistics Society

PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-SECOND ANNUAL MEETING OF THE BERKELEY LINGUISTICS SOCIETY February 10-12, 2006 GENERAL SESSION and PARASESSION on THEORETICAL APPROACHES TO ARGUMENT STRUCTURE Edited by Zhenya Antić Michael J. Houser Charles B. Chang Clare S. Sandy Emily Cibelli Maziar Toosarvandani Jisup Hong Yao Yao Berkeley Linguistics Society Berkeley, CA, USA Berkeley Linguistics Society University of California, Berkeley Department of Linguistics 1203 Dwinelle Hall Berkeley, CA 94720-2650 USA All papers copyright © 2012 by the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0363-2946 LCCN 76-640143 Printed by Sheridan Books 100 N. Staebler Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS A note regarding the contents of this volume ........................................................ vi Foreword ............................................................................................................... vii GENERAL SESSION Verb Second, Subject Clitics, and Impersonals in Surmiran (Rumantsch) .............3 STEPHEN R. ANDERSON Cross-linguistic Variation in a Processing Account: The Case of Multiple Wh-questions ..........................................................................................................23 INBAL ARNON, NEIL SNIDER, PHILIP HOFMEISTER, T. FLORIAN JAEGER, and IVAN A. SAG Several Problems for Predicate Decompositions ...................................................37 JOHN BEAVERS and ITAMAR FRANCEZ Wh-Conditionals in Vietnamese and Chinese: Against Unselective Binding .......49 BENJAMIN BRUENING -

An Chengri an Chengri, Male, Born in November, 1964.Professor. Director

An Chengri , male, born in November, 1964.Professor. Director of Institute of International Studies, Department of Political Science, School of philosophy and Public Administration,Heilongjiang University. Ph. D student of Japanese politics and Diplomacy History, NanKai University,2001.Doctor(International Relations History), Kokugakuin University,2002. Research Orientation: Japanese Foreign Relations, International Relation History in East Asia Publications: Research on contemporary Japan-South Korea Relations(China Social Science Press,October,2008);International Relations History of East Asia(Jilin Science Literature Press,March,2005) Association: Executive Director of China Institute of Japanese History , Director of China Society of Sino-Japanese Relations History Address: No.74 Xuefu Road, Nangang District, Haerbin, Heilongjiang, Department of Political Science, School of philosophy and Public Administration,Heilongjiang University. Postcode: 150080 An shanhua , Female, born in July,1964. Associate Professor, School of History, Dalian University. Doctor( World History),Jilin University,2007. Research Orientation: Modern and contemporary Japanese History, Japanese Foreign Relations, Political Science Publications: Comparative Studies on World Order View of China Korea and Japan and their Diplomatic in Modern Time ( Japanese Studies Forum , Northeast Normal University, 2006); Analysis of Japan's anti-system ideology towards the international system ( Journal of Changchun University of Science and Technology , Changchun University,2006) -

Silva Iaponicarum 日林 Fasc. Xxxii/Xxxiii 第三十二・三十三号

SILVA IAPONICARUM 日林 FASC. XXXII/XXXIII 第第第三第三三三十十十十二二二二・・・・三十三十三三三号三号号号 SUMMER/AUTUMN 夏夏夏・夏・・・秋秋秋秋 2012 SPECIAL EDITION MURZASICHLE 2010 edited by Aleksandra Szczechla Posnaniae, Cracoviae, Varsoviae, Kuki MMXII ISSN 1734-4328 2 Drodzy Czytelnicy. Niniejszy specjalny numer Silva Iaponicarum 日林 jest juŜ drugim z serii tomów powarsztatowych i prezentuje dorobek Międzynarodowych Studenckich Warsztatów Japonistycznych, które odbyły się w Murzasichlu w dniach 4-7 maja 2010 roku. Organizacją tego wydarzenia zajęli się, z pomocą kadry naukowej, studenci z Koła Naukowego Kappa, działającego przy Zakładzie Japonistyki i Sinologii Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Warsztaty z roku na rok (w momencie edycji niniejszego tomu odbyły się juŜ czterokrotnie) zyskują coraz szersze poparcie zarówno władz uczestniczących Uniwersytetów, Rady Kół Naukowych, lecz przede wszystkim Fundacji Japońskiej oraz Sakura Network. W imieniu organizatorów redakcja specjalnego wydania Silvy Iaponicarum pragnie jeszcze raz podziękować wszystkim Sponsorom, bez których udziału organizacja wydarzenia tak waŜnego w polskim kalendarzu japonistycznym nie miałaby szans powodzenia. Tom niniejszy zawiera teksty z dziedziny językoznawstwa – artykuły Kathariny Schruff, Bartosza Wojciechowskiego oraz Patrycji Duc; literaturoznawstwa – artykuły Diany Donath i Sabiny Imburskiej- Kuźniar; szeroko pojętych badań kulturowych – artykuły Krzysztofa Loski (film), Arkadiusza Jabłońskiego (komunikacja międzykulturowa), Marcina Rutkowskiego (prawodawstwo dotyczące pornografii w mediach) oraz Marty -

Day 1 (July 21, Monday)

DAY 1 (JULY 21, MONDAY) Registration 08:00-10:00 Registration & Refreshments IMH Opening Ceremony Opening : Dr. Suk-Jin Chang (President, CIL18) Welcoming Address: Dr. Ferenc Kiefer (President, CIPL) Dr. Ik-Hwan Lee (Co-chair, CIL18 LOC) Young-Se Kang 10:00-11:30 Dr. Chai-song Hong (President, LSK; Co-chair, CIL18 LOC) IMH (Kookmin Univ) Congratulatory Address: Dr. Sang-Gyu Lee (Director, National Institute of the Korean Language) Dr. Ki-Soo Lee (President, Korea Univ) Forum Lecture 1 1 Time Author & Title Moderator Site Sun-Hee Kim Laurence R. Horn (Yale Univ) 11:30-12:30 (Seoul Women's IMH Pragmatics and the lexicon Univ) Forum Lecture 2 2 Sun-hae Hwang Susan Fischer (UC San Diego) 14:00-15:00 (Sookmyung IMH Sign language East and West Women's Univ) Topic 1: Language, mind and brain 3 J.W. Schwieter (Wilfrid Laurier Univ) At what stage is language selected in bilingual speech production?: Investigating Hye-Kyung Kang 15:20-16:50 factors of bilingualism 302 (Open Cyber Univ) Il-kon Kim & Kwang-Hee Lee (Hanyang Univ) Boundedness of nouns and the usage of English articles Topic 2: Information structure 4 Samek-Lodovici , Vieri (UCL) Topic, focus and discourse-anaphoricity in the Italian clause Peter W. Culicover (Ohio State Univ) & Susanne Winkler (Univ of Tübingen) Dong-Young Lee 15:20-16:50 202 Focus and the EPP in English focus inversion constructions (Sejong Univ) Andreas Konietzko (Univ of Tübingen) The syntax and information structure of bare noun ellipsis Topic 3: Language policy 5 Karsten Legère (Univ of Gothenburg) Empowering African -

The Genji Monogatari

The Genji Monogatari - “A Loose Sequence of Vague Phrases” ? Thomas Evelyn McAuley Ph. D. The School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London ProQuest Number: 10731386 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731386 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract of Thesis In the thesis I test the hypothesis that Late Old Japanese (LOJ) is not, as has been claimed by a number of scholars, a language that is innately “vague”, but that it is capable of conveying meaning clearly. To prove this I analyse the text of the Genji Monogatari in a number of ways. I study the usage of honorifics in the text and the relationship between honorific usage and court rank. I show that honorific usage very often obviates the need for grammatical subjects and objects, and where honorifics or the context are not sufficient, the author introduces subjects to clarify the meaning of the text. Furthermore, I demonstrate that over brief sections of text, one character might be “tagged” with a particular honorific in order to identify them. -

Journal LA Bisecoman

JOURNAL LA SOCIALE VOL. 01, ISSUE 01 (001-004), 2020 A Sociolinguistic Study on the Development of Grammar System of Treatment Expression Akira Yonemoto Faculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University, Japan Corresponding Author: Akira Email: [email protected] Article Info Abstract Article history: Analysis of the language in which honorific expressions are developed Received 08 January 2020 has revealed various findings. The social and cultural background can be Received in revised form 15 considered by analyzing the history of the honorifics, etc., but the January 2020 honorifics are often used in colloquial language. Is also an issue of this Accepted 22 January 2020 research. Since honorifics reflect not only their practical aspects but also society, culture, and ideas, it is one clue to know from the history and usage of honorifics, and there is room for sociolinguistic analysis and Keywords: consideration. Is an area where there are still many. Honorific Expression Culture Society Introduction The honorific is a special expression for expressing respect or politeness by changing the way to state the same thing, and is one of the treatment expressions. Expressions of respect can be expressed in any language, but not many languages have grammatical and lexical systematic expressions. Typical languages include Japanese, Korean, Javanese, Vietnamese, Tibetan, Bengali, and Tamil. In order for treatment expressions to become grammatically and lexically systematically form, not only the influence of the original language but also the need for various respect expressions from the social background have emerged as honorific expressions. it is conceivable that. For this reason, in this paper, Japanese is an isolated word, Korean is also an isolated word, Javanese is a Malay-Polynesian Sunda-Sulawesi group, and Pet-Muong is an Austro-Asian Mon-Khmer group. -

Past Project Titles

Structure of Japanese Spring 2019 Sample titles from past projects • Interesting to see how informative—or not—a title can be when removed from its paper! Phonology and phonetics Japanese Rap Rhymes and Phonological Similarity Contraction with Sino-Japanese Roots Japanese Adaptation of Loanwords Pitch-Accent Analysis: Comparing the Tokyo dialect to the Ensyuu dialect F0 Differences in the Case Marking and the Postpositional ni Particle Acquisition of Lexical Strata in Japanese Loanwords [grad student] Morphology Mimetic Categorization: An analyis of Akita's model Noun-verb compounds and pro A Limited Exploration of Facultative Animacy in Japanese as Revealed Through Plural Usage Differences in the te-iru Conjugation in the Japanese Language The Structure of Japanese Honorifics Nominalization in Japanese Japanese Verb Inflection: Models of Processing Rendaku: Is it more prevalent in one syntactic category? The Case of Rendaku Immunity Syntax and semantics Is da a copula? Null pronouns Kansai Dialects and Types of ni Constraints on the use of Japanese conditional markers The Function of -wa in Japanese Discourse Representing Scrambling: A Parser Using Tree-Adjoining Grammar Japanese psych-verbs: A window into traditional approaches to psych-verbs [grad student] Sociolinguistics Giving Orders: A Comparison of Japanese Male and Female Speech Sentence Final Particles and Gender in Japanese Effects of Gender Role and Politeness on Pitch Understanding Japanese First-Person Pronoun Usage with Regards to Age and Social Hierarchy Changing Polite Speech (Keigo) Second-language acquisition English L1 Japanese L2 speakers’ production of geminate stops Syllable/Mora Structure and Language Learners Japanese gairaigo’s effect on English L2 acquisition for native Japanese speakers. -

Honorifics and Politeness in Japanese

TNI Journal of Business Administration and Languges Vol.2 No.2 July - December 2014 Honorifics and Politeness in Japanese Saowaree Nakagawa Graduate School, Program in Master of Business and Administration (Japanese Business) Thai-Nichi Institute of Technology [email protected] Abstract— The objective of the present study is to find the IIȵLiterature Review meanings and functions of Japanese honorifics and the expressions for expressing politeness in communication. The findings of the present study are as follows: 1) 2.1 Honorifics Teichoogo (courteous language) in Japanese honorifics is Honorifics are used to show respect and they are used semantically different from Kenjoogo (humble language) in in many social situations such as a situation in business that it does not have affects toward the listeners. And it is setting. Honorifics are basically used to mark social different from Teineigo (polite language) because it implies disparity in rank or to emphasize similarity in rank. the meaning of humbleness. 2) Japanese Honorifics hold two linguistic meanings and functions; they express respectful Honorifics in Japanese are generally divided into meaning and they differentiate ranks at work. 3) The three main categories, they are: explanation of the meanings and usages of honorifics in 1) Sonkeigo (respectful language) Japanese must be given in a discourse level. 4) Politeness Sonkeigo is usually a special form used when talking can be expressed by the selections of words. Thus, the to superiors (including teachers) and customers. knowledge of honorifics and the linguistic performance in Respectful language can express by substitute verbs with expressing politeness are the extremely crucial. 5) Japanese the following forms: honorifics and the appropriate Japanese expressions for ‘politeness’ are significant elements in communication. -

Japanese Politeness in the Work of Fujio Minami1 (南不二男) Barbara Pizziconi [email protected]

SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics Vol. 13 (2004): 269-280 Japanese politeness in the work of Fujio Minami1 (南不二男) Barbara Pizziconi [email protected] 0. Introduction This paper originates in a re-examination of the Japanese literature on Linguistic Politeness, at a time when an exhaustive and final answer to the question of what Politeness really is seems as elusive as it has ever been. Japanese works on Japanese linguistics remain virtually unknown to the non- Japanese-speaking public2, a fact motivated more by the lack of translations than intrinsic scholarly value. While the idea of discussing Linguistic Politeness without reference to one of the languages in which its structure and use are most sophisticated rightly sounds implausible, it is a fact that a good century of Japanese writings on the topic remain accessible only to the Japanese speaking public. Interestingly, the contribution of two Japanese linguists to the general debate on Politeness - I am referring here to Sachiko Ide’s (1989) and Yoshiko Matsumoto’s (1988, 1989, 1993) works3 - has been instrumental in the re-appraisal of the practically absolute dominion of the field by Brown and Levinson’s theoretical framework (see Pizziconi, 2003). Had such contributions not been delivered in English, they would hardly have achieved the same impact on the global arena. Such widely known Japanese scholarship in English, however, has clearly not developed in a vacuum. Data from Japanese language have contributed enormously to the whole debate on politeness, and Japanese scholarship has been able to provide fertile avenues of investigation. Widening our perspective on the Japanese approaches to the study of Politeness is the first reason for a translation of Fujio Minami’s work. -

Japanese Guide 4-5 V1

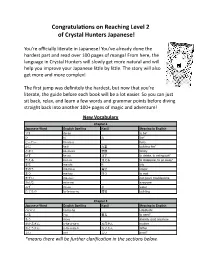

Congratulaons on Reaching Level 2 of Crystal Hunters Japanese! You’re officially literate in Japanese! You’ve already done the hardest part and read over 100 pages of manga! From here, the language in Crystal Hunters will slowly get more natural and will help you improve your Japanese liAle By liAle. The story will also get more and more complex! The first jump was definitely the hardest, But now that you’re literate, the guide Before each Book will Be a lot easier. So you can just sit Back, relax, and learn a few words and grammar points Before diving straight Back into another 100+ pages of magic and adventure! New Vocabulary Chapter 4 Japanese Word English Spelling Kanji Meaning in English です de-su to be* ひ hi 火 fire* ヒーロー hi-i-ro-o hero かじ ka-ji 火事 building fire* かぞく ka-zo-ku 家族 family けす ke-su 消す to delete, to extinguish* きえる ki-e-ru 消える to disappear, to go away* まち ma-chi 町 city まほう ma-ho-u 魔法 magic まつ ma-tsu 待つ to wait まずい ma-zu-i not good, troublesome みんな mi-n-na everyone みず mi-zu 水 water たてもの ta-te-mo-no 建物 building Chapter 5 Japanese Word English Spelling Kanji Meaning in English ハハハ! ha-ha-ha HAHAHA! いる i-ru 要る to need* もう mo-u already, (not) anymore おかあさん o-ka-a-sa-n お母さん mother おとうさん o-to-u-sa-n お父さん father よい yo-i 良い good* *means there will be further clarification in the sections below.