History of the Gatty Marine Laboratory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MD14 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

MD14 bus time schedule & line map MD14 Blebocraigs - Madras College View In Website Mode The MD14 bus line (Blebocraigs - Madras College) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Pitscottie: 2:57 PM (2) St Andrews: 7:53 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest MD14 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next MD14 bus arriving. Direction: Pitscottie MD14 bus Time Schedule 29 stops Pitscottie Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 2:57 PM New Madras College, St Andrews Tuesday 3:57 PM Old Course Hotel, St Andrews Wednesday 2:57 PM Grannie Clark's Wynd, St Andrews Thursday 3:57 PM Gibson Place, St Andrews Friday 1:07 PM Alexandra Place, St Andrews Alexandra Place, St Andrews Saturday Not Operational Bridge Street - South, St Andrews Southƒeld, St Andrews Fire Station, St Andrews MD14 bus Info Largo Road, St Andrews Direction: Pitscottie Stops: 29 Animal Hospital, St Andrews Trip Duration: 31 min Line Summary: New Madras College, St Andrews, Morrisons, St Andrews Old Course Hotel, St Andrews, Grannie Clark's Wynd, John Knox Road, St Andrews St Andrews, Alexandra Place, St Andrews, Bridge Street - South, St Andrews, Fire Station, St Andrews, Winram Place, St Andrews Animal Hospital, St Andrews, Morrisons, St Andrews, John Knox Road, St Andrews Winram Place, St Andrews, Cairnsden Gardens, St Andrews, Moir Crescent, St Andrews, Leonard Cairnsden Gardens, St Andrews Gardens, Bogward, Radernie Place, Bogward, Carron Bridge, Bogward, Balnacarron House, St Andrews, Moir Crescent, St Andrews -

Action Programme Accompanies Fifeplan by Identifying What Is Required to Implement Fifeplan and Deliver Its Proposals, the Expected Timescales and Who Is Responsible

1 THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK 2 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Spatial Strategy 3. Strategic Transport Proposals 4. Education 5. Strategic Development Areas/ Strategic Land Allocations 6. Settlement Proposals 7. Policies 8. Appendix 3 1. Introduction 1.1 The FIFEplan Local Development Plan was adopted on 21 September 2017 (Click here to view Adopted FIFEplan) it sets out the Council’s planning strategies and policies to guide and manage future development in Fife. It describes where and how the development will take place in the area over the 12 years from 2014-2026 to meet the future environmental, economic, and social needs, and provides an indication of development beyond this period. FIFEplan is framed by national and regional policy set by the National Planning Framework and the two Strategic Development Plans. Other strategic policies and Fife Council corporate objectives also shape the land use strategy as illustrated below. 4 1.2 This Action Programme accompanies FIFEplan by identifying what is required to implement FIFEplan and deliver its proposals, the expected timescales and who is responsible. Throughout the preparation of the plan, Fife Council has maintained close partnerships with key stakeholders, the Scottish Government, and other organisations named in the document. These organisations have a responsibility to alert the Council of any changes to the proposals. The Action Programme is important to Fife Council because the implementation of FIFEplan will require actions across different Council services. •The LDP Action Programme FIFEplan lists the infrastructure required to support Action Programme development promoted by the Plan •The Council prepares their Plan for Fife business plan for the year. -

Flat 4 10 Links Crescent, St Andrews, Fife

FLAT 4 10 LINKS CRESCENT, ST ANDREWS, FIFE FLAT 4 10 LINKS CRESCENT, ST ANDREWS, FIFE KY16 9HP REFURBISHED FLAT IN PRIME ST ANDREWS SETTING Fully upgraded flat in annexe of Victorian villa Ground and first floor. Own front door New kitchen & shower rooms. Solid oak flooring Close to world famous Old Course Well placed for university, shops, pubs and restaurants Hall, Living Room and Kitchen Principal Bedroom with En Suite Shower Room Bedroom 2, Shower Room Shared Grounds, Own Green EPC = D savills.co.uk DIRECTIONS DESCRIPTION Driving into St Andrews on the A91, 10 Links Crescent, is on the right hand side directly opposite The Flat 4, 10 Links Crescent is a ground and first floor flat in a stone built annexe behind a Victorian villa. Rusacks Hotel. The property has been fully refurbished and redecorated with solid oak flooring throughout the ground floor. A new kitchen and shower rooms have been installed. Go down the drive to the side of the house to reach the front door to Flat 4. The front door gives access to a hall with the living room off. It has a fireplace with a multi fuel stove and recessed shelves with a cupboard below. SITUATION 10 Links Crescent is situated in the row of substantial Victorian villas to the south side of the main road Opposite the living room is the new fitted kitchen with Baumatic microwave and oven, Bosch gas hob into St Andrews which runs parallel to The Links and the famous Old Course. The entrance to the with extractor fan above, Belfast sink, integrated fridge, dishwasher and washing machine. -

Breakfast Programme

The Celebration of the Wedding of HRH Prince William of Wales & Miss Catherine Middleton Site Map 2 About the Event Today, two of St Andrews’ most famous recent graduates are due to be married in Westminster Abbey in London with the eyes of the world upon them. As the town in which they met and their relationship blossomed, we are delighted to be able to welcome you to our celebrations in honour of the Royal Couple, HRH Prince William of Wales and Miss Catherine Middleton. A variety of entertainment and activities await, building up towards the big moment at around 10:45am where the Royal Couple will be making their entrance into the Abbey for the ceremony itself (due to start at 11am). This will be shown live on the large outdoor screen situated in the main Quadrangle. The “Wedding Breakfast” will be served from 8am on the lower lawn from the marquee with a selection of hot and cold food/drink available. Food will also be on sale throughout the day from local vendors. After the ceremony, and the traditional ‘appearance at the balcony’ the entertainment on the main stage will pick up again, taking the party on to 4pm. The main purpose of the day, aside from having fun, is to raise money for the Royal Wedding Charitable Fund. The list of charities we will be collecting for appears later in the programme. Most of what you see today is provided for free, but we would encourage you to please give generously. The organising committee hope you enjoy this momentous occasion and we are sure you will join with us in extending our warmest wishes and heartfelt congratulations to “Wills & Kate” as they look forward to a long and happy life together. -

FC Draft Habitats Regulations Appraisal

FIFE plan Dra Habitats Regulaons Appraisal : Environmental Report Annex 6 Fife Local Development Plan Proposed Plan October 2014 FC OiUfeN C I L Economy, Planning & Employability Services Glossary Appropriate Assessment - part of the Habitats Regulations Appraisal process, required where the plan is likely to have a significant effect on a European site, either alone or in combination with other plans or projects Birds Directive - Directive 2009/147/EC of the European Parliament and of the European Council of 30th November 2009 on the conservation of wild birds. BTO tetrad data - bird counts based on 2km by 2km squares carried out by the British Trust for Ornithology Natura 2000/European sites - The Europe-wide network of Special Protection Areas and Special Areas of Conservation, intended to provide protection for birds in accordance with the Birds Directive, and for the species and habitats listed in the Habitats Directive. Special Area of Conservation (SAC) - Area designated in respect of habitats and/or species under Articles 3 – 5 of the EC Habitats Directive. All SACs are European sites and part of the Natura 2000 network. Special Protection Area (SPA) - Area classified in respect of bird species under Article 4 of the Birds Directive. All SPAs are European sites and part of the Natura 2000 network. i Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 2.0 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................ -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

19 New Park Place St. Andrews, Fife

19 NEW PARK PLACE ST. ANDREWS, FIFE 19 NEW PARK PLACE ST. ANDREWS, FIFE, KY16 9LL Three bedroom flat in private development Second floor flat in modern building Entrance shared with four others in block of eight Underfloor heating and security entry system Dedicated parking space Shared grounds adjoining Lade Braes Open plan living room with kitchen & utility room 3 bedrooms & 2 bathrooms and shower room South facing balcony from principal bedroom 1,381 ft 2 EPC = B Savills Edinburgh Wemyss House 8 Wemyss Place Edinburgh EH3 6DH Tel: 0131 247 3738 Email: [email protected] savills.co.uk DIRECTIONS Driving into St Andrews on the A91, turn right onto City Road and right again at the second roundabout into Argyle Street which continues into Hepburn Gardens (B939). At the roundabout continue straight to stay on Hepburn Gardens. New Park Place is on the left. Drive into the development and continue past the houses. 19 New Park Place is in the last building on the right. SITUATION New Park Place has a wonderful setting in the historic town of St. Andrews. The development is about a mile from the Westport at the end of South Street with all of its shops and restaurants. The shared grounds adjoin the Lade Braes which is a belt of woodland with a footpath that leads from the countryside to the west of St Andrews all the way into the centre of town. St Andrews is renowned worldwide as the ‘Home of Golf’. The Old Course is a regular host to the Open Championship which will next be staged there in 2022. -

Adopted Fifeplan Final Document Reduced Size.Pdf

PEOPLE ECONOMY PLACE FIFE plan Fife Local Development Plan Adopted Plan Economy, Planning & September 2017 Employability Services Adopted FIFEplan, July 2017 1 Written Statement FIFEplan PEOPLE ECONOMY PLACE Ordnance Survey Copyright Statement The mapping in this document is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © crown copyright and database right (2017). All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey licence number 100023385. 2 Adopted FIFEplan, July 2017 Alternative languages and formats This document is called the Proposed FIFEplan Local Development Plan. It describes where and how the development will take place in the area over the 12 years from 2014-2026 to meet the future environmental, economic, and social needs, and provides an indication of development beyond this period. To request an alternative format or translation of this information please use the telephone numbers below. The information included in this publication can be made available in any language, large print, Braille, audio CD/tape and British Sign Language interpretation on request by calling 03451 55 55 00. Calls cost 3 to 7p per minute from a UK landline, mobile rates may vary. The informaon included in this publicaon can be made available in any language, large print, Braille, audio CD/tape and Brish Sign Language interpretaon on 7 3 03451 55 55 77 request by calling 03451 55 55 00. Calls cost 3 to 7p per minute from a UK landline, mobile rates may vary. Sa to informacje na temat dzialu uslug mieszkaniowych przy wladzach lokalnych Fife. Aby zamowic tlumaczenie tych informacji, prosimy zadzwonic pod numer 03451 55 55 44. -

(VIP) Programme Businesses Updated 05/12/2017

VisitScotland Information Partner (VIP) programme businesses Updated 05/12/2017 Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire Angus Argyll and Bute City of Edinburgh Clackmannanshire Comhairle nan Eilean Siar Dumfries and Galloway Dundee City East Ayrshire East Lothian East Renfrewshire Falkirk Fife Glasgow City Highland Inverclyde Midlothian Moray North Ayrshire North Lanarkshire Orkney Perth and Kinross Renfrewshire Scottish Borders Shetland Isles South Ayrshire South Lanarkshire Stirling West Dunbartonshire West Lothian Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire Duff House Adelphi Guest House Ambleside B&B Arden Guest House Ardoe House Hotel Arkaig Guest House Balmoral Castle Broadsea Sarah's Showcase (Butterworth Gallery) Castle Fraser Cedars Guest House Craigievar Castle Crathes Castle Creag Meggan Deans Shortbread Factory Gift Shop Deeside Activity Park Drum Castle Fraserburgh Heritage Centre Fyvie Castle The Gordon Guest House Ardmuir (& Eastwood/Westlea/Studio) Grampian Transport Museum Granville Guest House Potarch Lodge Ballater Lge,Glenesk,Glenclova,Sholfield,Glencairn Holmhead Cottage Huntly Castle Huntly Castle Caravan Park Castle Hotel The Jays Guest House Kellockbank Country Emporium Kirktown Garden Centre Maryculter House Hotel Museum of Scottish Lighthouses Palm Court Hotel Royal Lochnagar Distillery Aberdeen Science Centre Craibstone Estate Hunter Hall Station Hotel Portsoy Tarland Camping & Caravanning Club Site The Old School Boyndie Crathie Opportunity Holidays The Marcliffe Hotel and Spa Tolquhon Castle Wester Bonnyton Farm Caravan Site Woodside of -

School Name POSTCODE AUCL Eligible If Taken GCSE's at This

School Name POSTCODE AUCL Eligible if taken GCSE's at this AUCL Eligible if taken A-levels at school this school City of London School for Girls EC2Y 8BB No No City of London School EC4V 3AL No No Haverstock School NW3 2BQ Yes Yes Parliament Hill School NW5 1RL No Yes Regent High School NW1 1RX Yes Yes Hampstead School NW2 3RT Yes Yes Acland Burghley School NW5 1UJ No Yes The Camden School for Girls NW5 2DB No No Maria Fidelis Catholic School FCJ NW1 1LY Yes Yes William Ellis School NW5 1RN Yes Yes La Sainte Union Catholic Secondary NW5 1RP No Yes School St Margaret's School NW3 7SR No No University College School NW3 6XH No No North Bridge House Senior School NW3 5UD No No South Hampstead High School NW3 5SS No No Fine Arts College NW3 4YD No No Camden Centre for Learning (CCfL) NW1 8DP Yes No Special School Swiss Cottage School - Development NW8 6HX No No & Research Centre Saint Mary Magdalene Church of SE18 5PW No No England All Through School Eltham Hill School SE9 5EE No Yes Plumstead Manor School SE18 1QF Yes Yes Thomas Tallis School SE3 9PX No Yes The John Roan School SE3 7QR Yes Yes St Ursula's Convent School SE10 8HN No No Riverston School SE12 8UF No No Colfe's School SE12 8AW No No Moatbridge School SE9 5LX Yes No Haggerston School E2 8LS Yes Yes Stoke Newington School and Sixth N16 9EX No No Form Our Lady's Catholic High School N16 5AF No Yes The Urswick School - A Church of E9 6NR Yes Yes England Secondary School Cardinal Pole Catholic School E9 6LG No No Yesodey Hatorah School N16 5AE No No Bnois Jerusalem Girls School N16 -

Fife Local Development Plan Ac on Programme

PEOPLE ECONOMY PLACE FIFE plan Fife Local Development Plan FC OiUfeN C I L Acon Programme Economy, Planning & October 2014 Employability Services 2 Contents Introduction Table 1 Employment Proposals Table 2 Housing Proposals Table 3 Strategic Development Area Proposals Table 4 Housing Opportunity Proposals Table 5 Development Opportunity Proposals Table 6 Other Development Proposals Table 7 Policies Action Programme – Proposed FIFEplan Local Development Plan – October 2014 Introduction 1 Role and Purpose 1. This Action Programme accompanies the FIFEplan Local Development Plan. The preparation of an Action Programme to accompany a Local Development Plan is a requirement of the Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006 (Section 21) as explained in Circular 6/2013: Development Planning. 2. A Proposed Action Programme for FIFEplan must be published and submitted to Scottish Ministers alongside the proposed FIFEplan Local Development Plan and adopted and published within 3 months of the adoption of FIFEplan. The timetable for this process is set out in Section 3 of the FIFEplan Written Statement. 3. This is the first edition of the Proposed FIFEplan Local Development Plan Action Programme. The Action Programme is an ongoing working document, complementing FIFEplan by identifying actions required to progress its Proposals and Policies and facilitating their delivery. These actions will be monitored and an updated Action Programme published at least every two years. 4. It is intended that the Action Programme can be developed to show the linkages between proposals for development and the delivery of infrastructure and coordinate activity in identifying priorities and funding. 5. The following Tables 1 – 6 present the Proposals according to the type of land use proposed and include information which shows progress with their development. -

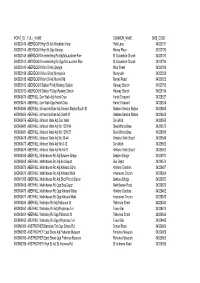

SMS Stop Codes221105

POINT_ID FULL_NAME COMMON_NAME SMS_CODE 6500D0143 ABERDOUR High St Adj Woodside Hotel Park Lane 34323787 6500D0144 ABERDOUR High St Opp Garage Manse Place 34323786 6500D0146 ABERDOUR Inverkeithing Rd Adj McLauchlan Rise St Columba's Church 34323783 6500D0145 ABERDOUR Inverkeithing Rd Opp McLauchlan Rise St Columba's Church 34323784 6500D0140 ABERDOUR Main St Adj Garage Main Street 34323834 6500D0139 ABERDOUR Main St Adj Morayvale Morayvale 34323828 6500D0138 ABERDOUR Main St Adj Murrell Rd Murrell Road 34323832 6500D0142 ABERDOUR Station Pl Adj Railway Station Railway Station 34323793 6500D0760 ABERDOUR Station Pl Opp Railway Station Railway Station 34323794 6500K0474 ABERHILL Den Walk Adj Heriot Cres Heriot Crescent 34328527 6500K0475 ABERHILL Den Walk Opp Heriot Cres Heriot Crescent 34328534 6500K0464 ABERHILL Kinnarchie Brae Adj Service Station/South St Bawbee Service Station 34328645 6500K0459 ABERHILL Kinnarchie Brae Adj South St Bawbee Service Station 34328638 6500K0476 ABERHILL Kirkland Walk Adj Den Walk Den Walk 34328565 6500K0480 ABERHILL Kirkland Walk Adj No 102/104 Steel Works Brae 34328572 6500K0481 ABERHILL Kirkland Walk Adj No 125/127 Steel Works Brae 34328568 6500K0478 ABERHILL Kirkland Walk Adj No 38-44 Kirkland Walk (East) 34328548 6500K0477 ABERHILL Kirkland Walk Adj No 6-12 Den Walk 34328562 6500K0479 ABERHILL Kirkland Walk Adj No 65-71 Kirkland Walk (East) 34328563 6500K0458 ABERHILL Methilhaven Rd Adj Bawbee Bridge Bawbee Bridge 34328673 6500K0468 ABERHILL Methilhaven Rd Adj Bus Depot Bus Depot 34328573 6500K0472 ABERHILL