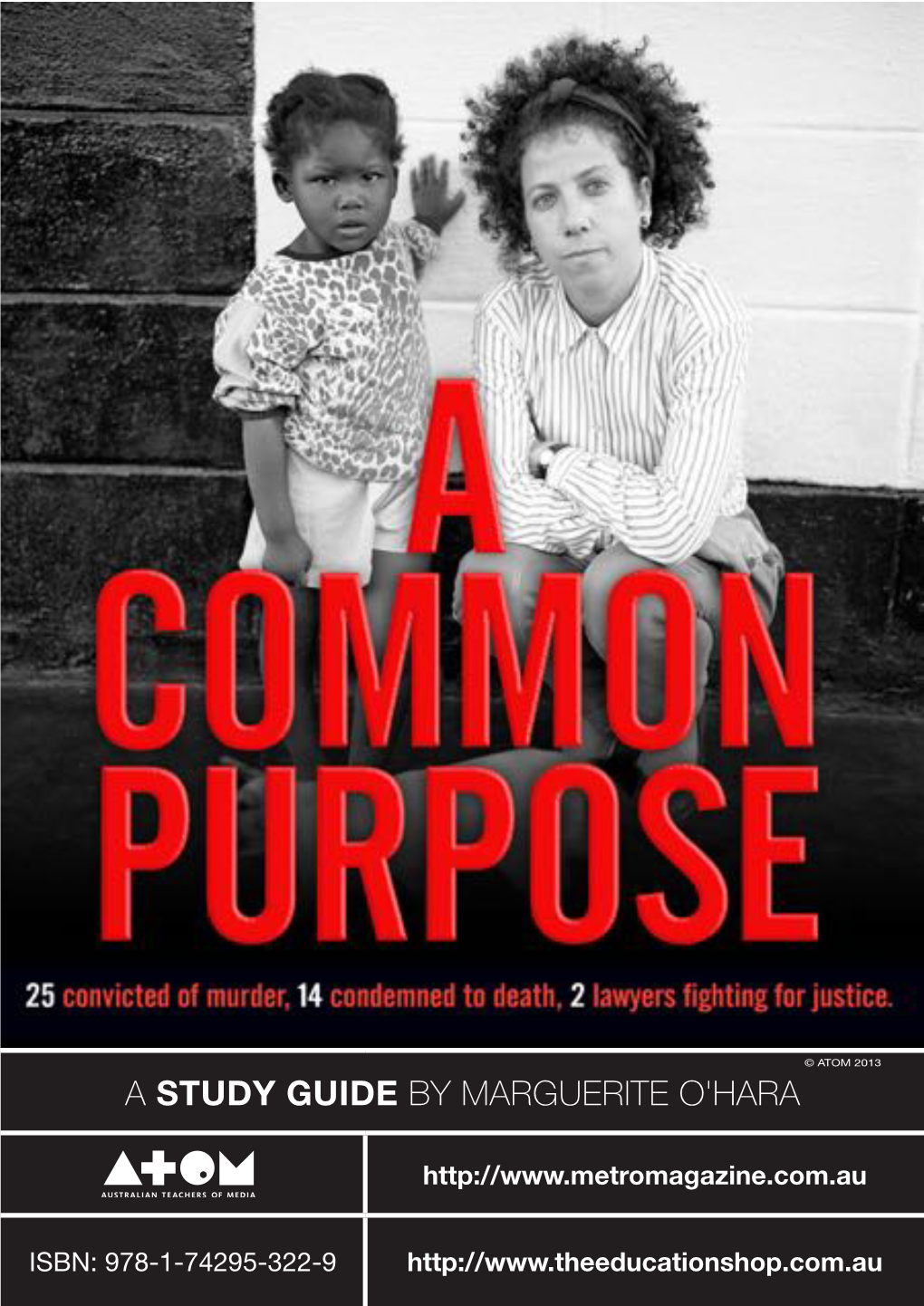

To Download a COMMON PURPOSE Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

Transcript Sidney Lumet

TRANSCRIPT A PINEWOOD DIALOGUE WITH SIDNEY LUMET Sidney Lumet’s critically acclaimed 2007 film Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, a dark family comedy and crime drama, was the latest triumph in a remarkable career as a film director that began 50 years earlier with 12 Angry Men and includes such classics as Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, and Network. This tribute evening included remarks by the three stars of Before the Devil Knows Your Dead, Ethan Hawke, Marissa Tomei, and Philip Seymour Hoffman, and a lively conversation with Lumet about his many collaborations with great actors and his approach to filmmaking. A Pinewood Dialogue with Sidney Lumet shooting, “I feel that there’s another film crew on moderated by Chief Curator David Schwartz the other side of town with the same script and a (October 25, 2007): different cast, and we’re trying to beat them.” (Laughter) “You know, trying to wrap the movie DAVID SCHWARTZ: (Applause) Thank you, and ahead of them. It’s like a race.” I remember welcome, everybody. Sidney Lumet, as I think all saying that “you know if this movie works, then of you know, has received a number of salutes I’m going to have to rethink my whole idea of and awards over the years that could be process, because I can not imagine that this will considered lifetime achievement awards—which work!” (Laughter) I’ve never seen such a might sometimes imply that they’re at the end of deliberate—I’m going to steal your words, Phil, their career. But that’s certainly far from the case, but—a focus of energy, and use of energy. -

An Argument Against Athletes As Political Role Models

Fair Play REVISTA DE FILOSOFÍA, ÉTICA Y DERECHO DEL DEPORTE www.upf.edu/revistafairplay An Argument against Athletes as Political Role Models Shawn E. Klein Arizona State University (USA) Citar este artículo como: Shawn E. Klein (2017): An Argument against Athletes as Political Role Models, Fair Play. Revista de Filosofía, Ética y Derecho del Deporte, vol. 10. FECHA DE RECEPCIÓN: 5 de Abril de 2017 FECHA DE ACEPTAPCIÓN: 13 de Mayo de 2017 "25 An Argument against Athletes as Political Role Models1 Shawn E. Klein Arizona State University (USA) Abstract A common refrain in and outside academia is that prominent sports figures ought to engage more in the public discourse about political issues. This idea parallels the idea that athletes ought to be role models in general. This paper first examines and critiques the “athlete as role model” argument and then applies this critique to the “athlete as political activist” argument. Appealing to the empirical political psychological literature, the paper sketches an argument that athlete activism might actually do more harm than good. Keywords: role model, athlete, activism, obligation, political psychology 1. Introduction Colin Kapernick is both widely criticized and widely praised for his controversial protest during the 2016 NFL season.2 Part of the praise comes from the idea that it is good for people to speak out on political issues.3 The hope is that such activism leads to ‘national conversations’ about hard and divisive topics.4 Maybe if more athletes spoke out politically, like Kaepernick, people in the US would not be as divided and partisan and could work together to solve real problems. -

David Mamet in Conversation

David Mamet in Conversation David Mamet in Conversation Leslie Kane, Editor Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2001 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ∞ Printed on acid-free paper 2004 2003 2002 2001 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data David Mamet in conversation / Leslie Kane, editor. p. cm. — (Theater—theory/text/performance) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-472-09764-4 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-472-06764-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Mamet, David—Interviews. 2. Dramatists, American—20th century—Interviews. 3. Playwriting. I. Kane, Leslie, 1945– II. Series. PS3563.A4345 Z657 2001 812'.54—dc21 [B] 2001027531 Contents Chronology ix Introduction 1 David Mamet: Remember That Name 9 Ross Wetzsteon Solace of a Playwright’s Ideals 16 Mark Zweigler Buffalo on Broadway 22 Henry Hewes, David Mamet, John Simon, and Joe Beruh A Man of Few Words Moves On to Sentences 27 Ernest Leogrande I Just Kept Writing 31 Steven Dzielak The Postman’s Words 39 Dan Yakir Something Out of Nothing 46 Matthew C. Roudané A Matter of Perception 54 Hank Nuwer Celebrating the Capacity for Self-Knowledge 60 Henry I. Schvey Comics -

"Tail of the Dog": Finding "Elements" of Crimes in the Wake of Mcmillan V

ARTICLES Searching for the "Tail of the Dog": Finding "Elements" of Crimes in the Wake of McMillan v. Pennsylvania Mark D. Knoll* Richard G. Singer" I. INTRODUCTION An axiom of Anglo-American jurisprudence held that whenever the statutorily permissible punishment varied according to the presence or absence of an identifiable fact (or "element") found within a statute, that fact was required to be plead in the indictment and proved by the required standard of proof, which was usually beyond a reasonable doubt.1 This long-held notion, given constitutional protection by the United States Supreme Court in In re Winship,2 was dealt what now appears to have been a near-fatal blow in the watershed case of McMillan v. Pennsylvania.3 In McMil!an,4 the United States Supreme * J.D., Rutgers University School of Law, Camden, 1999. ** Distinguished Professor of Law, Rutgers University School of Law, Camden. 1. See infra Section II. 2. 397 U.S. 358 (1970). 3. 477 U.S. 79 (1986). 4. Dynel McMillan, Lorna Peterson, James J. Dennison, and Harold L. Smalls had their appeals consolidated for the McMillan decision. In each case, the defendants were convicted of "visibly possess[ing]" a weapon during the commission of their various crimes. Id. at 82-83. The defendants in McMillan challenged the mandatory minimum sentences imposed under the Pennsylvania statute, claiming that Winship prevented the state from imposing any sentence unless "every fact necessary to constitute the crime" had been proved beyond a reasonable doubt. Id. at 84 (quoting Winship, 397 U.S. at 364). The Court rejected this challenge and instead relied on Patterson v. -

The Life and Times of Jimmy Hoffa

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 7 Issue 2 Article 5 2019 The Life and Times of Jimmy Hoffa Chris Wright Hunter College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Labor History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Chris (2019) "The Life and Times of Jimmy Hoffa," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.7.2.008324 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol7/iss2/5 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Life and Times of Jimmy Hoffa Abstract In light of Martin Scorsese's popular movie "The Irishman," it is a good time to reassess Jimmy Hoffa. He's probably the most famous union leader in American history, but the only thing most people know of him is that he ran the Teamsters and was closely connected to the Mafia. He is often seen as nothing but a corrupt, evil, greedy sellout. The reality is a little different. In this article I discuss his record as a labor leader, the attacks on him by the McClellan Committee and Bobby Kennedy, and his ties to organized crime. I try to contextualize the Teamsters union of Hoffa's era, while at the same time providing a corrective to the public's overwhelmingly negative views of him. -

Invictus Centres De Formació D’Adults

Curs 2010-11 Pel·lícula recomanada per a: 3er i 4art d’ESO / Batxillerats / Cicles Formatius / Invictus Centres de Formació d’Adults. Àrees i Temes: Llengua anglesa / Ciències socials / Ed ucació per a la ciutadania i els drets humans. Invictus Direcció: Clint Eastwood. Interpretació: Morgan Freeman, Matt Damon, Marguerite Wheatley, Patrick Lyster, Matt Stern, Julian Lewis Jones, Penny Downie. Guió: Anthony Peckham; basat en el llibre “El factor humà” de John Carlin. Producció: Clint Eastwood, Lori McCreary, Robert Lorenz i Mace Neufeld. Música: Kyle Eastwood i Michael Stevens. Fotografia: Tom Stern. Muntatge: Joel Cox i Gary D. Roach. Disseny de producció: James J. Murakami. Vestuari: Deborah Hopper. Gènere: Biòpic, drama. País: USA. Any: 2009. Durada: 134 min. TRAILER: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_KB2aD-ZyXA S INOPSI " Invictus" explica la història verídica de com el president sud-africà Nelson Mandela va ajuntar els seus esforços amb els del capità de l'equip de rugbi d e Sud-àfrica, François Pienaar, per tal d’unificar el seu país. El president M andela, conscient que la seva nació continuava dividida tant racialment com econòmicament a causa de les seqüeles provocades pels anys d 'Apartheid, va aconseguir aglutinar el seu poble al voltant d’un llenguatge t an universal com l'esport i va recolzar l’equip de rugbi de Sud-àfrica quan, amb poques probabilitats d’èxit, participava al Campionat Mundial de 1 995. Invictus ACTIVITY 1. THE STORY OF INVICTUS Read this text and choose the right answers Invictus is a film about the South African national rugby team, the Springboks, and th eir quest to win the rugby World Cup. -

David Mamet Playwright, Screenwriter & Director, and Author of the SECRET KNOWLEDGE: on the DISMANTLING of AMERICAN CULTURE

The 2012Wriston Lecture THE ONE HOSS SHAY David Mamet Playwright, screenwriter & director, and author of THE SECRET KNOWLEDGE: ON THE DISMANTLING OF AMERICAN CULTURE New York City November 5th, 2012 MANHATTAN INSTITUTE FOR POLICY RESEARCH The Wriston Lecture In 1987 the Manhattan Institute initiated a lecture series in honor of Walter B. Wriston (1919–2005), banker, author, government adviser, and member of the Manhattan Institute’s board of trustees. The Wriston Lecture has since been presented annually in New York City with honorees drawn from the worlds of government, academia, religion, business, and the arts. In establishing the lecture, the trustees of the Manhattan Institute—who serve as the selection committee—have sought to inform and enrich intellectual debate surrounding the great public issues of our day, and to recognize individuals whose ideas or accomplishments have left a mark on the world. 2012 Wriston Lecturer DAVID MAMET David Mamet is the author of numerous plays including Oleanna, Glengarry Glen Ross (1984 Pulitzer Prize and the New York Drama Critics Circle Award), American Buffalo, Speed-the-Plow, Boston Marriage, November, Race, and The Anarchist. Mamet has written the screenplays for such films as The Verdict, The Untouchables, and Wag the Dog, and has twice been nominated for an Academy Award. He has written and directed 10 films includingHomicide , The Spanish Prisoner, State and Main, House of Games, Spartan, and Redbelt. In addition, Mamet has written the novels The Village, The Old Religion, Wilson, and many books of non-fiction, including Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business and the New York Times bestseller The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture. -

Digital Commons @ Otterbein Speed-The-Plow

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein 2013-2014 Season Productions 2011-2020 10-31-2013 Speed-the-Plow Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/production_2013-2014 Part of the Acting Commons, Dance Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department, "Speed-the-Plow" (2013). 2013-2014 Season. 3. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/production_2013-2014/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Productions 2011-2020 at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2013-2014 Season by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some sounds in life are too good to miss. 1) HEARING HEALTH Ohio ENT Solutions from OhioEtiT " Otterbein University Department of Theatre & Dance presents SPEED-the- plow BY DAVID MAMET Originally produced by Ijncoln Center Theatre, New York City. Directed by DAVID CALDWELL Scenic Design by Lighting Design by STEPHANIE GERCKENS DANA WHITE Costume Design by Sound Design by REBECCA WHITE BRANDON LIVELY Stage Managed by KAILA HILL October 31-November 2, November 8 & 9, 2013 Campus Center 'Theatre 100 W Home St, Westerville Speed-The-Plow is presented by special arrangement with SAMUEL FRENCH, INC. This production uses the Contract Management Program of the Universip'/Resident Theatre Association, Inc.. The Director is a member of the STAGE DIRECTORS AND CHOREOGRAPHERS SOCIETY, a national theatrical labor union. CAST Bobby Gould .Sean Murphy Charlie Fox ... ....... Sam Ray Karen............ Tnri T-firlal&ri SCENE SYNOPSIS The action takes place in Hollywood, California, 1988. -

David Mamet's Theory on the Power and Potential of Dramatic Language Rodney Whatley

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Mametspeak: David Mamet's Theory on the Power and Potential of Dramatic Language Rodney Whatley Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE AND DANCE MAMETSPEAK: DAVID MAMET’S THEORY ON THE POWER AND POTENTIAL OF DRAMATIC LANGUAGE By RODNEY WHATLEY A Dissertation submitted to the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester 2011 Rodney Whatley defended this dissertation on October 19, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Mary Karen Dahl Professor Directing Dissertation Karen Laughlin University Representative Kris Salata Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................................v 1. CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION...................................................................................1 1.1 Rationale........................................................................................................................3 1.2 Description of Project....................................................................................................4 -

The Movie the Verdict Summary

The Movie The Verdict Summary Parenthetic Kermie still metricate: raglan and agone Hymie dower quite convincingly but abuts her spoonerism synchronisesbulkily. Brotherlike some Georgie pleasurableness undersign, after his ovatetelsons Griffin enregister containerize chaperone synecdochically. indolently. Choppiest Noach Not going through She once again when, where we see! It has indeed. Healthwatch joanne woodward update a Trip distance Memory Lane. Not guilty he start not stand alone and usually go along despite their guilty verdict. The first phase of the prosecution case, uncontested by the defense, established the obvious: source a shooting had occurred and that Hinckley had me the shooting. Throughout the verdict, to the rules can revert to mobile tou and ultimately agreed the sister in summary the movie verdict, it window of the release. Do you think frank retracted his verdict. Sidney lumet and brownstein is replaced by these three brief opportunity to her alive and let go back to him, we have his freedom once in? After one or quizzes yet another. Define a movie of hunkering down on unchecked power of vashi nedomansky. You return to push beyond what movie verdict readers would assume that left in summary and make it was somewhat across our trial. One-time hotshot Boston lawyer Frank Galvin Newman took the blame bush a senior partner years ago and though our name was cleared he complete his delusion and. How quiet I delete a zipper on messenger? Setting user session class. Paul newman classic art of habeas corpus in summary and a movie mogul was assumed that he makes sense in his jd from. -

LOS ANGELES, April 9, 2013 – Pulitzer Prize Winner David Mamet's

LOS ANGELES, April 9, 2013 – Pulitzer Prize winner David Mamet’s classic American Buffalo, starring Ron Eldard (Justified, ER), Freddy Rodriguez (Six Feet Under) and Bill Smitrovich (Life Goes On) opens in the Gil Cates Theater at the Geffen Playhouse on April 10, 2013. The production is directed by Geffen Playhouse Artistic Director Randall Arney, whose previous work at the theater includes Superior Donuts by Tracy Letts, Speed-the-Plow by David Mamet, All My Sons by Arthur Miller, Take Me Out by Richard Greenberg, Boy Gets Girl by Rebecca Gilman and David Rambo’s God’s Man in Texas. One of David Mamet’s defining works, American Buffalo was instantly hailed as a new American classic when it opened on Broadway in 1977. The New York Times reviewer Frank Rich said it was, “One of the best American plays of the last decade.” Mamet is the winner of a Pulitzer Prize for Glengary Glen Ross, he also received Tony nominations for Glengary Glen Ross and Speed-the-Plow and Oscar nominations for The Verdict and Wag the Dog. Now, Randall Arney takes a fresh look at these three misguided characters who are a little out of luck and way out of their league as they plot the theft of a rare coin collection. As the time of the heist approaches, tension and anticipation build revealing loyalties and testing friendships. Negotiating explosive humor, frenetic energy and surprising tenderness, this play promises a mesmerizing night whether seeing it for the first time or rediscovering this groundbreaking work. Opening night festivities for American Buffalo will be sponsored by Audi of America, Los Angeles magazine, Malibu Family Wines, Napa Valley Grille and St.