Instrument Teaching in the Context of Oral Tradition: a Field Study from Bolu, Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SILK ROAD: the Silk Road

SILK ROAD: The Silk Road (or Silk Routes) is an extensive interconnected network of trade routes across the Asian continent connecting East, South, and Western Asia with the Mediterranean world, as well as North and Northeast Africa and Europe. FIDDLE/VIOLIN: Turkic and Mongolian horsemen from Inner Asia were probably the world’s earliest fiddlers (see below). Their two-stringed upright fiddles called morin khuur were strung with horsehair strings, played with horsehair bows, and often feature a carved horse’s head at the end of the neck. The morin khuur produces a sound that is poetically described as “expansive and unrestrained”, like a wild horse neighing, or like a breeze in the grasslands. It is believed that these instruments eventually spread to China, India, the Byzantine Empire and the Middle East, where they developed into instruments such as the Erhu, the Chinese violin or 2-stringed fiddle, was introduced to China over a thousand years ago and probably came to China from Asia to the west along the silk road. The sound box of the Ehru is covered with python skin. The erhu is almost always tuned to the interval of a fifth. The inside string (nearest to player) is generally tuned to D4 and the outside string to A4. This is the same as the two middle strings of the violin. The violin in its present form emerged in early 16th-Century Northern Italy, where the port towns of Venice and Genoa maintained extensive ties to central Asia through the trade routes of the silk road. The violin family developed during the Renaissance period in Europe (16th century) when all arts flourished. -

01 M.Gp Acilis Konseri 2019.Indd

VAR VAR OLMA OLMA NIN NIN KARAN AYDIN LIĞI LIĞI 47. İSTANBUL MÜZİK FESTİVALİ 11-30 HAZİRAN 2019 AÇILIŞ KONSERİ OPENING CONCERT TEKFEN FiLARMONi ORKESTRASı tEKFEN PHıLHARMONıC ORCHEStRA AZIZ SHOKHAKIMOV şef conductor SEONG-JIN CHO piyano piano (XVII. Uluslararası Fryderyk Chopin Piyano Yarışması Birincisi XVII. International Fryderyk Chopin Piano Competition Winner) SUNUŞ PRESENTATION AÇILIŞ KONSERİ OPENING CONCERT Değerli Konuklar, Hayatı, müziği, kültürü ve sanatı, tüm aydınlığı ve renkliliğiyle yaşayacağımız, tekfen filarmoni orkestrası ruhumuzu zenginleştirecek bir festival bizi bekliyor. Yıldız solistler, genç yetenekler, tekfen phılharmonıc orchestra büyük orkestralar yine festivalde İstanbul izleyicisiyle buluşacak. Şehrin tarihi mekânlarında düzenlenen konserler İstanbul’un kültürel zenginliğini göz önüne AZIZ SHOKHAKIMOV şef conductor serecek. Her yaştan müziksevere hitap eden ücretsiz hafta sonu etkinlikleriyle SEONG-JIN CHO piyano piano festival, geniş kitlelere ulaşacak. (XVII. Uluslararası Fryderyk Chopin Piyano Yarışması Birincisi Kentimizin en köklü klasik müzik etkinliği olan bu festivali, İstanbul Kültür Sanat XVII. International Fryderyk Chopin Piano Competition Winner) Vakfı olarak, 1973 yılından bu yana, kesintisiz olarak sürdürüyoruz. İstanbul’un sanat yaşamını zenginleştirmek, dünya kültür birikimine katkıda bulunmak ve gençlere 11.06.2019 Lütfi Kırdar Kongre ve Sergi Sarayı destek olabilmek, her zaman en önemli hedeflerimiz arasında yer alıyor. Verdiğimiz SA tu 20.00 Lütfi Kırdar Convention and Exhibition Centre eser siparişleriyle dünya kültür birikimine katkıda bulunmaya devam ediyoruz. Bu yıl da festivalde Zeynep Gedizlioğlu’nun ve Alexander Tchaikovsky’nin yeni eserlerini Ludwig van Beethoven dinlemek için sabırsızlanıyoruz. Gençlerin kültür yaşamına erişim ve katılımını Piyano Konçertosu No. 1, Do Majör, Op. 15 artırmak için İKSV Kültür-Sanat Kart projesini sürdürüyor, tüm konservatuvar Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Major, Op. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

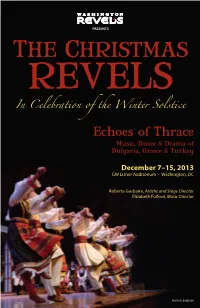

Read This Year's Christmas Revels Program Notes

PRESENTS THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey December 7–15, 2013 GW Lisner Auditorium • Washington, DC Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director PHOTO BY ROGER IDE THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey The Washington Featuring Revels Company Karpouzi Trio Koleda Chorus Lyuti Chushki Koros Teens Spyros Koliavasilis Survakari Children Tanya Dosseva & Lyuben Dossev Thracian Bells Tzvety Dosseva Weiner Grum Drums Bryndyn Weiner Kukeri Mummers and Christmas Kamila Morgan Duncan, as The Poet With And Folk-Dance Ensembles The Balkan Brass Byzantio (Greek) and Zharava (Bulgarian) Emerson Hawley, tuba Radouane Halihal, percussion Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director Gregory C. Magee, Production Manager Dedication On September 1, 2013, Washington Revels lost our beloved Reveler and friend, Kathleen Marie McGhee—known to everyone in Revels as Kate—to metastatic breast cancer. Office manager/costume designer/costume shop manager/desktop publisher: as just this partial list of her roles with Revels suggests, Kate was a woman of many talents. The most visibly evident to the Revels community were her tremendous costume skills: in addition to serving as Associate Costume Designer for nine Christmas Revels productions (including this one), Kate was the sole costume designer for four of our five performing ensembles, including nineteenth- century sailors and canal folk, enslaved and free African Americans during Civil War times, merchants, society ladies, and even Abraham Lincoln. Kate’s greatest talent not on regular display at Revels related to music. -

Yayını Görüntülemek Için Tıklayın

Prof. Sir John Boardman Sir John Boardman’ın 90. Yaşı Onuruna In Honour of Sir John Boardman on the Occasion of his 90th Birthday TÜBA-AR Türkiye Bilimler Akademisi Arkeoloji Dergisi Turkish Academy of Sciences Journal of Archaeology Sayı: 20 Volume: 20 2017 TÜBA-AR TÜBA Arkeoloji (TÜBA-AR) Dergisi TÜBA-AR uluslararası hakemli bir TÜRKİYE BİLİMLER AKADEMİSİ ARKEOLOJİ DERGİSİ dergi olup TÜBİTAK ULAKBİM (SBVT) ve Avrupa İnsani Bilimler Referans TÜBA-AR, Türkiye Bilimler Akademisi (TÜBA) tarafından yıllık olarak yayın- İndeksi (ERIH PLUS) veritabanlarında lanan uluslararası hakemli bir dergidir. Derginin yayın politikası, kapsamı ve taranmaktadır. içeriği ile ilgili kararlar, Türkiye Bilimler Akademisi Konseyi tarafından belir- lenen Yayın Kurulu tarafından alınır. TÜBA Journal of Archaeology (TÜBA-AR) TÜBA-AR is an international refereed DERGİNİN KAPSAMI VE YAYIN İLKELERİ journal and indexed in the TUBİTAK ULAKBİM (SBVT) and The European TÜBA-AR dergisi ilke olarak, dönem ve coğrafi bölge sınırlaması olmadan Reference Index for the Humanities arkeoloji ve arkeoloji ile bağlantılı tüm alanlarda yapılan yeni araştırma, yo- and the Social Sciences (ERIH PLUS) databases. rum, değerlendirme ve yöntemleri kapsamaktadır. Dergi arkeoloji alanında yeni yapılan çalışmalara yer vermenin yanı sıra, bir bilim akademisi yayın organı Sahibi / Owner: olarak, arkeoloji ile bağlantılı olmak koşuluyla, sosyal bilimlerin tüm uzmanlık Türkiye Bilimler Akademisi adına Prof. Dr. Ahmet Cevat ACAR alanlarına açıktır; bu alanlarda gelişen yeni yorum, yaklaşım, analizlere yer veren (Başkan / President) bir forum oluşturma işlevini de yüklenmiştir. Sorumlu Yazı İşleri Müdürü Dergi, arkeoloji ile ilgili yeni açılımları kapsamlı olarak ele almak için belirli Managing Editor bir konuya odaklanmış yazıları “dosya” şeklinde kapsamına alabilir; bu amaçla Prof. -

בעזרת ה' Yagel Harush- Musical C.V ID- 066742438 Birth Date-10.28.1984

בעזרת ה' Yagel Harush- Musical C.V ID- 066742438 Birth Date-10.28.1984 Married + 4 Teaches Mediterranean music. Composer and Musical adapter. Plays Kamancheh and Ney. Discography 2016- working on a diwan (anthology of Jewish liturgical poems) which he wrote and composed. The vision is to publish an anthology of liturgical poems for the first time in years.These are Modern day poems written by Yagel, and will be published alongside a disc which includes melodies for a number of the poems the book contains. The composition is based on the "Maqam" – the module system typical to eastern poetics. 2016- Founding Shir Yedidut ensemble, which renews and performs parts of the Bakashot, a tradition of Moroccan Jewry. In charge of musical adaption, lead singer and plays a number of insrtuments (Kamancheh, Ney, Oud and guitar), and research of the Bakashot traditions of Moroccan Jewry. As a part of the project a disc was produced by the name of "Aira Shachar" alongside the concert. The disc and the concert features well known artists David Deor, Erez Lev Ari and Yishai Rivo, as well as dozens of other leading musicians of eastern music style in the country. (Disc included) Alongside incorporation of elements from folk music, western harmony etc., the ensemble wishes to restore the gentle and unique sound of Mediterranean music. The main vision is to restore one of the richest poetic and musical traditions in our culture. The content of the poems- songs of longing to the country and wholeness of the individual as well as the nation, of pleading for the affinity of G-d and man- are as relevant to our lives today as ever. -

Narrative Instrumental Küi Performance: Action Through Music

Jason Torello Final Project Central Asian Music 297 12/09/20 Narrative Instrumental Küi Performance: Action through Music My final project was conceptualized out of the lecture and readings from week 6 Narrative and Instrumental Performance: Kazakh küi. I will be presenting a piece of original program music which is constructed around a quasi-epic narrative and crafted loosely into a Kui style. My project will include a piece of program music that I will write and perform on my bass guitar. Since the highest strings of the bass are tuned to a perfect forth, I thought there was a connection between those registers and the two stringed dombrya. I also have been developing a strumming and finger-picking style which hopefully will capture the gestures of the music I have been hearing this semester. I will only use the two strings to keep close as I can to the spirit of the dombrya sound. The performance will be put together as a 5-minute audiovisual program. The listeners can follow the portion of my essay explaining my reasoning and processes. I will use the technique on the dombrya of dividing the neck into four sections: bas bun (lowest register) negizgi bun, orta bun, and sagha (the highest register). I will use these divisions as compositional elements which I will arrange to go with an original story that reinforces some of the themes in the song. While the outline of the piece is laid out by the arrangement, the actual phrases will all be spontaneously composed on the spot in an attempt to convey the images I am seeing in my mind. -

Instrument List

Instrument List Africa: Europe: Kora, Domu, Begana, Mijwiz 1, Mijwiz 2, Arghul, Celtic & Wire Strung Harps, Mandolins, Zitter, Ewe drum collection, Udu drums, Doun Doun Collection of Recorders, Irish and other whistles, drums, Talking drums, Djembe, Mbira, Log drums, FDouble Flutes, Overtone Flutes, Sideblown Balafon, and many other African instruments. Flutes, Folk Flutes, Chanters and Bagpipes, Bodran, Hang drum, Jews harps, accordions, China: Alphorn and many other European instruments. Erhu, Guzheng, Pipa, Yuequin, Bawu, Di-Zi, Guanzi, Hulusi, Sheng, Suona, Xiao, Bo, Darangu Middle East: Lion Drum, Bianzhong, Temple bells & blocks, Oud, Santoor, Duduk, Maqrunah, Duff, Dumbek, Chinese gongs & cymbals, and various other Darabuka, Riqq, Zarb, Zills and other Middle Chinese instruments. Eastern instruments. India: North America: Sitar, Sarangi, Tambura, Electric Sitar, Small Banjo, Dulcimer, Zither, Washtub Bass, Native Zheng, Yuequin, Bansuris, Pungi Snake Charmer, Flute, Fife, Bottle Blows, Slide Whistle, Powwow Shenai, Indian Whistle, Harmonium, Tablas, Dafli, drum, Buffalo drum, Cherokee drum, Pueblo Damroo, Chimtas, Dhol, Manjeera, Mridangam, drum, Log drum, Washboard, Harmonicas Naal, Pakhawaj, Tamte, Tasha, Tavil, and many and more. other Indian instruments. Latin America: Japan: South American & Veracruz Harps, Guitarron, Taiko Drum collection, Koto, Shakuhachi, Quena, Tarka, Panpipes, Ocarinas, Steel Drums, Hichiriki, Sanshin, Shamisen, Knotweed Flute, Bandoneon, Berimbau, Bombo, Rain Stick, Okedo, Tebyoshi, Tsuzumi and other Japanese and an extensive Latin Percussion collection. instruments. Oceania & Australia: Other Asian Regions: Complete Jave & Bali Gamelan collections, Jobi Baba, Piri, Gopichand, Dan Tranh, Dan Ty Sulings, Ukeleles, Hawaiian Nose Flute, Ipu, Ba,Tangku Drum, Madal, Luo & Thai Gongs, Hawaiian percussion and more. Gedul, and more. www.garritan.com Garritan World Instruments Collection A complete world instruments collection The world instruments library contains hundreds of high-quality instruments from all corners of the globe. -

C Quliyev Bayati 2Cild.Pdf

Bayatı "ATLAS ENSEMBLE" üçün p a r t i t u r a *** Bayaty for "ATLAS ENSEMBLE" s c o r e ORCHESTRA: Flute / Piccolo Dizi / Xun in C Ney in C Suona / Guanzi in C Zurna in C Oboe Balaban in C Sheng 1 in C Sheng 2 in C Clarinetti in B / in A / Basso Clarinetto Pipa / Liugin in C Tar in C Ud in C Mandolin Kanun in C Zheng in C Santur in C Arpa Timpani Piatto sospeso Cinese tom-toms Tam-Tam Soprano Female khanende singer Violino Erhu in C Kamancha in D Kemenche in C Viola Viola da gamba Violoncello Contrabass ATLAS ENSEMBLE-nin (HOLLANDİYA) SİFARİŞİ İLƏ - 2004 COMMISSIONED BY ATLAS ENSEMBLE (NEDERLAND) - 2004 Bayatı Bayaty Cavanşir QULİYEV Javanshir GULIYEV q=135 > Piccolo > œ œ >œ œ œ œ œ >œ bœ œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ bœ œ œ œ Flute/Picc. 4 j œ œ #œ œ œ #œ œ °& 4 Œ ‰ œ J ‰ Dizi f > œ œ œ > œ œ >œ œ œ œ œ >œ bœ œ œ œ #œ œ bœ œ œ Dizi/xun inC 4 j œ œ #œ œ œ #œ œ & 4 Œ ‰ œ J ‰ f > > > #>œ œ œ œ œ œ Ney in C 4 j #œ œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ & 4 Œ ‰ œ œ œ œ J ‰ ¢ Guanzi f Suona/Guanzi in C 4 °& 4 j ‰ Œ Ó ∑ ∑ f œ > Zurna in C 4 œ & 4 ‰ Œ Ó ∑ ∑ f J > > œ œ >œ œ œ œ œ >œ bœ œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ bœ œ œ œ Oboe 4 j œ œ #œ œ œ #œ œ & 4 Œ ‰ œ J ‰ f > Balaban in C 4 j j œ œ œ & 4 Œ ‰ œ #œ œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ bœ œ œ œ ‰ #œ œ bœ œ œ ¢ f œ œ > œ > > Sheng in C 1 4 j °& 4 œ ‰ Œ Ó ∑ ∑ f Sheng in C 2 4 & 4 j ‰ Œ Ó ∑ ∑ f œ Cl. -

Electronic Musical Instruments DIGITAL PIANOS 2011 2012

Electronic Musical Instruments _DIGITAL PIANOS 2011_2012 411ENG-KAT-02 Cover photo: shot at Music- und Lifestyle-Hotel nhow in Berlin KeyboardsDigital pianos_High Grade 02 We love music. We live music. Electronics maker CASIO uses its tremendous creative energy to develop innovative products for leisure, school and office. Products that thrill, encourage learning and make businesses run more smoothly. In short, products that enrich our lives and help society progress. The difference we can make in this way is both our calling and our motivation. CASIO sees itself as a driving force in the industry, helping shape the flow of the market through revolutionary developments. In the area of music instruments, for example, CASIO has introduced advanced sound and functional properties into its introductory models, the kind of features that have previously been the exclusive domain of high-end product lines. We know from our own experience that making music with an instrument brings a unique personal enrichment – a piece of “aural” quality of life and an expression of joy and creativity. Music is also a universal, emotional language that links us together and bridges generations and cultures through- out the world. We want to make this special experience available to as many people as possible – with high-quality, affordable brand-name instruments from CASIO. Content CELVIANO Series Pages 04 to 11 PRIVIA Series Pages 12 to 21 03 COMPACT Series Pages 22 to 23 Technical Specifications Pages 24 to 25 Digital pianos_CELVIANO 04 The best sound has many facets www.celviano.eu For more than 20 years CASIO has given its heart and soul to the dream of piano playing. -

Alizadeh Behroozinia.Cdr

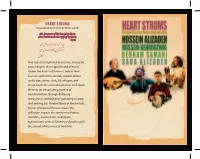

HEART STRUMS Reverberations from another world Oh, Strummer of the lute of my heart, Hear in this moan the reply of my heart. Rumi ای زﻪ زﻨﺪه رﺑﺎب دل ﻦ ﻮ ﻮ از اﻦ ﻮاب دل ﻦ ﻮﻮی Four top, accomplished musicians, envoys by whose ngers the magical hand of music strums the hearts of listeners, imbue their environs with other-worldly sounds whose rustle, tap, chime, clink, lilt, whisper, and croon touch the souls of audiences and squire them on an intoxicating journey of transformation through uttering restlessness, sobbing grief, galloping ecstasy, and swirling joy. Rooted rmly in the melodic frames of classical Persian music, this collection inspires the spirit in meditative, romantic, melancholic, and joyous explorations, even of listeners unfamiliar with the sounds of this musical tradition. Hossein Alizadeh, Behnam Samani, virtuoso acclaimed composer, percussionist who plays daf, a frame musicologist, teacher, and drum, and Tombak, a goblet drum, was an undisputed born in Iran and lives in Cologne, contemporary master of Germany. He has worked and played classical Persian music, was with the most prominent musicians and born in Tehran and lives in renowned masters of Iranian music, Iran. He is a virtuoso player rendering not only complex rhythms, of setar (three-string) and tar but also improvising unexpected (string), a Persian lute, which melodies. He is a founding member of is considered the "Sultan of the Zarbang ensemble and through his instruments". Celebrated for collaboration and performances with his refreshing world-class musicians in international improvisations, he is also an venues, has attracted audiences acknowledged preserver of unfamiliar with classical Iranian music to this art form. -

Kayhan Kalhor/Erdal Erzincan the Wind

ECM Kayhan Kalhor/Erdal Erzincan The Wind Kayhan Kalhor: kamancheh; Erdal Erzincan: baglama; Ulaş Özdemir: divan baglama ECM 1981 CD 6024 985 6354 (0) Release: September 26, 2006 After “The Rain”, his Grammy-nominated album with the group Ghazal, comes “The Wind”, a documentation of Kayhan Kalhor’s first encounter with Erdal Erzincan. It presents gripping music, airborne music indeed, pervasive, penetrating, propelled into new spaces by the relentless, searching energies of its protagonists. Yet it is also music firmly anchored in the folk and classical traditions of Persia and Turkey. Iranian kamancheh virtuoso Kalhor does not undertake his transcultural projects lightly. Ghazal, the Persian-Indian ‘synthesis’ group which he initiated with sitarist Shujaat Husain Khan followed some fifteen years of dialogue with North Indian musicians, in search of the right partner. “Because I come from a musical background which is widely based on improvisation, I really like to explore this element with players from different yet related traditions, to see what we can discover together. I’m testing the water – putting one foot to the left, so to speak, in Turkey. And one foot to the right, in India. I’m between them. Geographically, physically, musically. And I’m trying to understand our differences. What is the difference between Shujaat and Erdal? Which is the bigger gap? And where will this lead?” Kayhan began his association with Turkish baglama master Erdal Erzincan by making several research trips, in consecutive years, to Istanbul, collecting material, looking for pieces that he and Erdal might play together. He was accompanied on his journeys by musicologist/player Ulaş Özdemir who also served as translator and eventually took a supporting role in the Kalhor/Erzincan collaboration.