The Radio Conference 2009 Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcast and on Demand Bulletin Issue Number 377 29/04/19

Issue 377 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 29 April 2019 Issue number 377 29 April 2019 Issue 377 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 29 April 2019 Contents Introduction 3 Notice of Sanction City News Network (SMC) Pvt Limited 6 Broadcast Standards cases In Breach Sunday Politics BBC 1, 30 April 2017, 11:24 7 Zee Companion Zee TV, 18 January 2019, 17:30 26 Resolved Jeremy Vine Channel 5, 28 January 2019, 09:15 31 Broadcast Licence Conditions cases In Breach Provision of information Khalsa Television Limited 34 In Breach/Resolved Provision of information: Diversity in Broadcasting Various licensees 36 Broadcast Fairness and Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Symphony Environmental Technologies PLC, made on its behalf by Himsworth Scott Limited BBC News, BBC 1, 19 July 2018 41 Complaint by Mr Saifur Rahman Can’t Pay? We’ll Take It Away!, Channel 5, 7 September 2016 54 Complaint Mr Sujan Kumar Saha Can’t Pay? We’ll Take It Away, Channel 5, 7 September 2016 65 Tables of cases Investigations Not in Breach 77 Issue 377 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 29 April 2019 Complaints assessed, not investigated 78 Complaints outside of remit 89 BBC First 91 Investigations List 94 Issue 377 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 29 April 2019 Introduction Under the Communications Act 2003 (“the Act”), Ofcom has a duty to set standards for broadcast content to secure the standards objectives1. Ofcom also has a duty to ensure that On Demand Programme Services (“ODPS”) comply with certain standards requirements set out in the Act2. -

New Report Reveals Public Service Impact of Commercial Radio

May 16, 2011 NEW REPORT REVEALS PUBLIC SERVICE IMPACT OF COMMERCIAL RADIO RadioCentre, the industry body for commercial radio, today (May 16) released a new report, Action Stations: The Output and Impact of Commercial Radio, which highlights the industry’s investment in vital public service broadcasting such as news and information; cultural and social action; community involvement and charitable activities. The report is being backed by a nation-wide advertising campaign on commercial radio, highlighting the valuable contribution the industry makes to communities and local businesses. It follows on from commercial radio’s best–ever haul of 14 Golds at this year’s Sony Radio Academy Awards and record audience reach figures announced last week. The Action Stations report, which is the result of a substantial audit conducted across more than 160 commercial radio stations, shows that on average, some eight and a half hours of public service content are broadcast each week by commercial radio stations. Andrew Harrison, Chief Executive of RadioCentre said: “Commercial radio has been through some big changes in the last few years, with the launch of new national and regional brands offering a genuine alternative to the BBC. However, this report shows that is only part of the story. The vast majority of commercial stations are locally-focused and are still making a vital contribution to their communities by offering real public value. “Commercial radio achieved its biggest ever audience over the last quarter, with the potent combination of national networks and local services proving hugely successful in attracting listeners. This survey shows that these stations not only entertain, but also have a real impact on people’s lives.” The radio advertising campaign, which will be offered to all RadioCentre’s members, emphasises the importance of the stations’ relationships with their listeners, using the theme of ‘commercial radio, your radio’ to promote the notion and importance of a strong, thriving, local and regional commercial radio sector. -

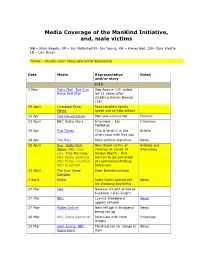

Media Coverage of the Mankind Initiative, And, Male Victims

Media Coverage of the ManKind Initiative, and, male victims MB – Mark Brooks, IM – Ian McNicholl,IY- Ian Young, KB – Kieron Bell, SW- Sara Westle LB – Lori Busch Yellow – denote court cases and initial disclosures Date Media Representative Detail and/or story 2018 3 May Daily Mail, The Sun, Zoe Adams (19) jailed News and Star for 11 years after stabbing Kieran Bewick (18) 29 April Liverpool Echo, Paul Lavelle’s family Metro speak out to help others 26 Apr The Conversation Men are victims too Feature 23 April BBC Radio Worc Interview – Ian Interview McNicholl 19 Apr The Times This is what it is like Article when your wife hits you 18 Apr The Sun Male victims statistics News 16 April Sun, Daily Mail, Alex Skeel victim of Articles and Metro, BBC Five violence at hands of interviews Live, This Morning, Jordan Worth - first BBC Radio Scotland, woman to be convicted BBC Three Counties, of coercive/controlling BBC Breakfast behaviour 13 April The Sun (Dear Dear Deirdre column Deirdre) 7 April Mirror Jodie Owen spared jail News for stabbing boyfriend 29 Mar Mail Nasreen Knight attacked husband Julian knight 27 Mar BBC Lavinia Woodward News appeal refused 27 Mar Wales Online New refuge in Bridgend News being set up 26 Mar BBC Radio Somerset Interview with Mark Interview Brooks 23 Mar Kent online, BBC ManKind call for refuge in News Radio Kent Kent 14-16 Mar Stoke Sentinel, BBC Pete Davegun fundraiser Radio Stoke, Crewe Guardian, Staffs Live 19 Mar Victoria Derbyshire Mark Brooks interview Interview 12 Mar Somerset Live ManKind Initiative appeal -

RISHI SUNAK SARATHA RAJESWARAN a Portrait of Modern Britain Rishi Sunak Saratha Rajeswaran

A PORTRAIT OF MODERN BRITAIN RISHI SUNAK SARATHA RAJESWARAN A Portrait of Modern Britain Rishi Sunak Saratha Rajeswaran Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Registered charity no: 1096300. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Trustees Daniel Finkelstein (Chairman of the Board), Richard Ehrman (Deputy Chair), Theodore Agnew, Richard Briance, Simon Brocklebank-Fowler, Robin Edwards, Virginia Fraser, David Frum, Edward Heathcoat Amory, David Meller, Krishna Rao, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, Charles Stewart-Smith and Simon Wolfson About the Authors Rishi Sunak is Head of Policy Exchange’s new Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) Research Unit. Prior to joining Policy Exchange, Rishi worked for over a decade in business, co-founding a firm that invests in the UK and abroad. He is currently a director of Catamaran Ventures, a family-run firm, backing and serving on the boards of various British SMEs. He worked with the Los Angeles Fund for Public Education to use new technology to raise standards in schools. He is a Board Member of the Boys and Girls Club in Santa Monica, California and a Governor of the East London Science School, a new free school based in Newham. -

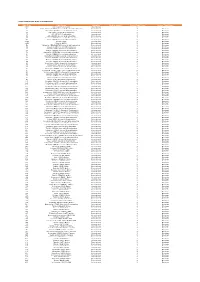

Codes Used in D&M

CODES USED IN D&M - MCPS A DISTRIBUTIONS D&M Code D&M Name Category Further details Source Type Code Source Type Name Z98 UK/Ireland Commercial International 2 20 South African (SAMRO) General & Broadcasting (TV only) International 3 Overseas 21 Australian (APRA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 36 USA (BMI) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 38 USA (SESAC) Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 39 USA (ASCAP) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 47 Japanese (JASRAC) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 48 Israeli (ACUM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 048M Norway (NCB) International 3 Overseas 049M Algeria (ONDA) International 3 Overseas 58 Bulgarian (MUSICAUTOR) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 62 Russian (RAO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 74 Austrian (AKM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 75 Belgian (SABAM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 79 Hungarian (ARTISJUS) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 80 Danish (KODA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 81 Netherlands (BUMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 83 Finnish (TEOSTO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 84 French (SACEM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 85 German (GEMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 86 Hong Kong (CASH) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 87 Italian (SIAE) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 88 Mexican (SACM) General & Broadcasting -

Independent Radio (Alphabetical Order) Frequency Finder

Independent Radio (Alphabetical order) Frequency Finder Commercial and community radio stations are listed together in alphabetical order. National, local and multi-city stations A ABSOLUTE RADIO CLASSIC ROCK are listed together as there is no longer a clear distinction Format: Classic Rock Hits Broadcaster: Bauer between them. ABBEY 104 London area, Surrey, W Kent, Herts, Luton (Mx 3) DABm 11B For maps and transmitter details see: Mixed Format Community Swansea, Neath Port Talbot and Carmarthenshire DABm 12A • Digital Multiplexes Sherborne, Dorset FM 104.7 Shropshire, Wolverhampton, Black Country b DABm 11B • FM Transmitters by Region Birmingham area, West Midlands, SE Staffs a DABm 11C • AM Transmitters by Region ABC Coventry and Warwickshire DABm 12D FM and AM transmitter details are also included in the Mixed Format Community Stoke-on-Trent, West Staffordshire, South Cheshire DABm 12D frequency-order lists. Portadown, County Down FM 100.2 South Yorkshire, North Notts, Chesterfield DABm 11C Leeds and Wakefield Districts DABm 12D Most stations broadcast 24 hours. Bradford, Calderdale and Kirklees Districts DABm 11B Stations will often put separate adverts, and sometimes news ABSOLUTE RADIO East Yorkshire and North Lincolnshire DABm 10D and information, on different DAB multiplexes or FM/AM Format: Rock Music Tees Valley and County Durham DABm 11B transmitters carrying the same programmes. These are not Broadcaster: Bauer Tyne and Wear, North Durham, Northumberland DABm 11C listed separately. England, Wales and Northern Ireland (D1 Mux) DABm 11D Greater Manchester and North East Cheshire DABm 12C Local stations owned by the same broadcaster often share Scotland (D1 Mux) DABm 12A Central and East Lancashire DABm 12A overnight, evening and weekend, programming. -

THE VOICE of UK COMMERCIAL Annual Review 2011

Annual Review 2011 THE VOICE OF UK COMMERCIAL Contents 03 CHAIRMAN’S REVIEW 04 CEO’S REVIEW RADIO 06 12 18 REVENUE DIGITAL ORGANISATION 10 14 AUDIENCE INFLUENCE RadioCentre | Annual Review 2011 01 // 2011 has been a year where radio has continued to buck the trend and confound its critics as the only traditional medium to grow revenue. // 02 RadioCentre | Annual Review 2011 Chairman’s Review Welcome to the RadioCentre Review of An industry-wide marketing campaign was When I meet with my colleagues on the 2011. The last twelve months have been an launched by the RAB under the umbrella RadioCentre board each quarter, we are impressive year for commercial radio, with theme of Britain Loves Radio, with a mindful of the importance of all these continuing record audiences and strong national advertising campaign helping to services and the need to balance both the revenue growth, especially against the deliver this message. differing priorities of different members, and recessionary backdrop for all businesses. work for a secure and prosperous future for RAB also tackled the historic challenge of a the sector. I hope that 2012 proves It has been a year where radio has lack of creativity in radio advertising, with successful for you and for everyone involved continued to buck the trend and confound an important partnership with D&AD, the in our industry. its critics, as the only traditional medium to membership organisation which represents grow revenue. And if the forecasts are to be excellence in the creative, design and believed there could be more good news in advertising communities. -

Groovefinder's Extra

Groovefnder's Extra - Radio July 2018 You’re confronted with all the music in the world but what the hell are you supposed to listen to? Somebody tell me! What’s good? Larry Stein, Director Steinhardt School of New York University This Document is part of a series, published in Groovefinder's World – Birke Beisert's Blog about Music & Lifestyle Https://groovefindersworld.com/groovefinders-extra Groovefnder's Extra - Radio July 2018 What is Radio? - Two Definitions It just means you listen to audio passively, linearly. In the old days a radio station was the frequency you tuned into for a programmer’s choice of airwaves. Now it could be a playlist somebody created, or a pre-programmed genre channel. A playlist is a radio. Paul Brenner, President of NextRadio Curation, taste-making, personalization - whatever you want to call the act of somebody plopping songs in front of you, the music equivalent of sitting down and asking for the chef’s recommendations without bothering to glance at the menu - is the future of music. It is the centerpiece of a music, in people’s private homes, in public spaces, in social gatherings. And if you ask anyone from the older, airwaves-loving generation: That’s also exactly what it’s always been. Amy X. Wang, QUARTZ Digital News Outlet Groovefnder's Extra - Radio July 2018 Why Radio is important for Artists and Labels? Groovefnder's Extra - Radio July 2018 Why Radio is important for Artists and Labels? Groovefnder's Extra - Radio July 2018 Groovefnder's Extra - Radio July 2018 Let's talk about Internet-Radio To make it easy: There are three types of stations • AM/FM-Stations which also run a digital platform • Online-Only-Stations, which are run as a business or part of a business • Online-Only-Stations, which are not run as a business, but for the love of music and (sometimes) the technique. -

Action Stations! the Output and Impact of Commercial Radio Action Contents Page

Action Stations! The Output and Impact of Commercial Radio Action Contents Page Forewords 2 Introduction 5 Industry overview 7 Economic impact 11 Community and social action 15 Stations! Music and entertainment 25 New technology 35 News and sport 41 Speech and debate 49 Appendix 55 Contents 1 A thriving and sustainable local media sector is a vitally Forewords important part of the democratic landscape. With over 300 stations across the country, commercial radio can play a crucial role in holding those with responsibility to account, in addition to fulfilling its core remit to provide entertainment and information. Commercial radio’s accessibility and availability means that it is able to deliver high quality national and local news, music, sport, speech, travel and weather reports to listeners across the UK. Many stations offer a distinctive local service to a specific geographic area, but there are also those stations that provide a community of like- minded music fans with the songs they love, those that bring together a community of people who share the same interests and those that serve ethnic minority communities. Commercial radio also plays an important economic role, particularly in local communities, where it supports local businesses by giving them a powerful means of communicating with local customers. In addition, stations are also highly effective in raising funds for specific charitable causes, increasing awareness of social issues and providing a forum for topical debate. I therefore welcome this report, celebrating the vital contribution made by commercial radio stations within their local communities, not only as a source of entertainment but also as a public service. -

Organisation Title Subjects Country Radio Rivadavia Dirección

Organisation Title Subjects Country Radio Rivadavia Dirección Periodística News Argentina FM 88.7 y AM 940 Conductor flashes informativos Argentina FM 100.3 Radio Universal Procuctor Argentina Canal 90 FM Stereo Host News Aruba Magic FM Director News Aruba 6MKA 98.3 Advertising Manager Advertising, News Australia 3MFM Station Manager Advertising, News Australia WA FM (Leederville) Music Director Arts Australia 5DN Creative Director Arts Australia ABC Classic FM Music Producer Arts Australia Mix 94.5 FM Music Director Arts Australia 2Day FM Assistant Music Director Arts, Radio News/Reviews Australia Magic 107.3 FM Music Director Arts, Radio News/Reviews Australia Mix 4MB 103.5 Morning Presenter Arts, Radio News/Reviews Australia NX FM Presenter Arts, Radio News/Reviews Australia i98 FM Drive Time Presenter Arts, Radio News/Reviews Australia 720 ABC Perth Intake Editor Lifestyle - General Australia 4TTT FM General Manager Management - General Australia 4AAA-FM General Manager Management - General Australia Cool Country FM Director of Operations Management - General Australia Hot FM (Roma) General Manager Management - General Australia Waringarri Radio 693 AM Development Director Management - General Australia 2HAY FM Manager Management - General Australia Radio Austral Station Director Management - General Australia River 94.9FM General Manager Management - General, News Australia 4EEE Station Manager Management - General, News Australia Ultra 106.five Presenter Management - General, News, Radio News/Reviews Australia 2DU Sales Manager Management -

Reaching Their Communities: the Participatory Nature of Ethnic Minority Radio Dr

Reaching their communities: the participatory nature of ethnic minority radio Dr. Eleanor Shember-Critchley ([email protected]) Department of Languages, Information and Communications, Manchester Metropolitan University Biography: Dr Eleanor Shember-Critchley is Lecturer in Digital Media and Web Development at the Department of Languages, Information and Communication at Manchester Metropolitan University. She recently completed her PhD entitled Ethnic Minority Radio: Interactions and Identity. This examined ethnic minority radio stations from across the UK, from public to illegal broadcasters. She worked with the staff and DJs to understand how identity and ethnicity were mediated as part of everyday life within each station and its community. Her research interests revolve around radio, its communities, audiences, identity and developing research methodologies for practitioners. Abstract: As part of a PhD thesis on ethnic minority radio and identity in the UK, this paper presents an analysis and discussion of the interactions between a station, the DJs and their communities to bring off truly social events. Ethnic minority radio stations have, in particular, developed complex and lively ways to make radio a truly participatory experience. The paper explores how DJs utilise text message, social networking, answered and unanswered calls, transcribed messages and on-air performance to enable participation. These resources come to life through sophisticated, unspoken rules mutually created between listener and DJ incorporating shared cultural competences cloaked to casual listeners. Drawing on an analysis of six case study stations the paper takes a qualitative approach utilising interview, observation and programme analysis. Giddens’ theory of Structuration (1984) is employed alongside Scannell (1996) and Moore’s (2005) work on radio with Karner’s structures of ethnicity (2007) to address the two main aspects of the paper: 1. -

DAB Multiplexes and Transmitters Frequency Finder

DAB Multiplexes and Transmitters Frequency Finder BBC NATIONAL Area Site kW: BBC D1 SD Grid Ref Maidstone, Medway, South Essex Bluebell Hill 6.3 6.3 - TQ 757 613 England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland (12B) Tunbridge Wells area, Kent Tunbridge Wells 3 1.46 - TQ 607 440 RADIO 1 New Music, Contemporary s BBC National +FM Tunbridge Wells, Kent St Marks 0.02 0.02 - TQ 582 375 1 XTRA Rhythmic New Music s BBC National Mid Kent Charing Hill 2 - - TQ 965 504 RADIO 2 Adult, Oldies, Mixed Music s BBC National +FM Ashford area Wye 0.5 0.5 - TR 066 472 RADIO 3 Classical s BBC National +FM Faversham area, Kent Faversham - 0.52 - TR 003 601 RADIO 4 (FM) Talk, News, Entertainment s BBC National +FM Canterbury and Faversham area Dunkirk 2 2 0.9 TR 078 590 RADIO 4 EXTRA Entertainment m BBC National Canterbury area Chartham 1 0.44 - TR 102 561 RADIO 5 LIVE News, Sport, Talk m BBC National +AM Thanet, Kent Thanet 0.7 0.174 - TR 366 678 5 LIVE SPORTS EXTRA Sport m BBC National Dover and Deal area, Kent Swingate 1 1 - TR 334 429 6 MUSIC Rock, Mixed Music s BBC National Dover and Folkestone area, Kent Dover 2 1 - TR 274 397 ASIAN NETWORK Asian m BBC National Folkestone Cretaway Down 0.25 - - TR 229 381 WORLD SERVICE News, Talk m BBC National Hythe, Kent Turnpike Hill 0.05 0.01 - TR 154 344 BBC 97% Coverage with new trans On-air 1995 (London area, 65% coverage by 1998) Rye, Sussex Rye 0.2 - - TQ 904 198 East Sussex Heathfield 5 2 - TQ 566 220 Hastings Hastings 3 1 - TQ 807 100 DIGITAL ONE NATIONAL Eastbourne, Sussex Eastbourne 0.3 1 - TV 615 986