Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number 164 23/08/10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcast and on Demand Bulletin Issue Number 377 29/04/19

Issue 377 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 29 April 2019 Issue number 377 29 April 2019 Issue 377 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 29 April 2019 Contents Introduction 3 Notice of Sanction City News Network (SMC) Pvt Limited 6 Broadcast Standards cases In Breach Sunday Politics BBC 1, 30 April 2017, 11:24 7 Zee Companion Zee TV, 18 January 2019, 17:30 26 Resolved Jeremy Vine Channel 5, 28 January 2019, 09:15 31 Broadcast Licence Conditions cases In Breach Provision of information Khalsa Television Limited 34 In Breach/Resolved Provision of information: Diversity in Broadcasting Various licensees 36 Broadcast Fairness and Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Symphony Environmental Technologies PLC, made on its behalf by Himsworth Scott Limited BBC News, BBC 1, 19 July 2018 41 Complaint by Mr Saifur Rahman Can’t Pay? We’ll Take It Away!, Channel 5, 7 September 2016 54 Complaint Mr Sujan Kumar Saha Can’t Pay? We’ll Take It Away, Channel 5, 7 September 2016 65 Tables of cases Investigations Not in Breach 77 Issue 377 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 29 April 2019 Complaints assessed, not investigated 78 Complaints outside of remit 89 BBC First 91 Investigations List 94 Issue 377 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 29 April 2019 Introduction Under the Communications Act 2003 (“the Act”), Ofcom has a duty to set standards for broadcast content to secure the standards objectives1. Ofcom also has a duty to ensure that On Demand Programme Services (“ODPS”) comply with certain standards requirements set out in the Act2. -

Audio-Based Fingerprinting for Radio Station Recommendations

AUDIO-BASED FINGERPRINTING FOR RADIO STATION RECOMMENDATIONS Stefan Langer, Markus Friedrich, Liza Obermeier, Emma Munisamy Andre´ Ebert Claudia Linnhoff-Popien∗ inovex GmbH LMU Munich, Mobile and Distributed Data Management and Analytics Systems Group andre.ebert@ifi.lmu.de [first name].[last name]@ifi.lmu.de ABSTRACT and precise station recommendations. This paper focuses on the latter and thus on the question how The world of linear radio broadcasting is characterized by a to generate meaningful recommendations for radio stations. wide variety of stations and played content. That is why find- Two main types of approaches can be distinguished for that: ing stations playing the preferred content is a tough task for a Recommendations based on Collaborative Filtering (CF) and potential listener, especially due to the overwhelming number Content-based Filtering (CBF) approaches. CF focuses on of offered choices. Here, recommender systems usually step user opinions and behavior, which can lead to privacy issues in but existing content-based approaches rely on metadata and as well as the Cold Start Problem (see Section 2). Thus, a thus are constrained by the available data quality. Therefore, CBF based recommender system working with characteris- we propose a new pipeline for the generation of audio-based tics derived from available station data is preferred in context radio station fingerprints relying on audio stream crawling of this work. In [1], it could be shown that station recom- and a deep autoencoder. We show that the proposed finger- mendation based on available metadata is possible, but only prints are especially useful for characterizing radio stations if the metadata reaches a certain quality level. -

The History of the Development of British Satellite Broadcasting Policy, 1977-1992

THE HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF BRITISH SATELLITE BROADCASTING POLICY, 1977-1992 Windsor John Holden —......., Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD University of Leeds, Institute of Communications Studies July, 1998 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others ABSTRACT This thesis traces the development of British satellite broadcasting policy, from the early proposals drawn up by the Home Office following the UK's allocation of five direct broadcast by satellite (DBS) frequencies at the 1977 World Administrative Radio Conference (WARC), through the successive, abortive DBS initiatives of the BBC and the "Club of 21", to the short-lived service provided by British Satellite Broadcasting (BSB). It also details at length the history of Sky Television, an organisation that operated beyond the parameters of existing legislation, which successfully competed (and merged) with BSB, and which shaped the way in which policy was developed. It contends that throughout the 1980s satellite broadcasting policy ceased to drive and became driven, and that the failure of policy-making in this time can be ascribed to conflict on ideological, governmental and organisational levels. Finally, it considers the impact that satellite broadcasting has had upon the British broadcasting structure as a whole. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract i Contents ii Acknowledgements 1 INTRODUCTION 3 British broadcasting policy - a brief history -

Ex-MI6 Men Cleared to Write in Book

PROFILE INSIDE ARTS SPORT 2-page sports There is My farewell Dame Kiri nothing like a MOMENTS OF calendar . to Channel 4 CA TASTROPHE Te Kanawa dame of the yearJ JEREMY ISAACS 6 PORTRAIT OF 1987 INTERVIEW 15 26, 27 I I BARRY HUMPHRIES 5 & A BRIEFLY SUMMIT MOVE Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze latest information, supplied to them Yemeni Embassy in London last they will be moved to a luxurious agreed to meetings with THE TWO British women sold by EILEEN MacDONALD week as brides in the Yemen Arab by The Observer , and was arranging , but was treated as a tourist house in Taiz with their husbands Us Secretary of State to interview the husbands with the HI¦Hiam ^2IIIIIQ9L i ^ H ^ i ^ B '^^ i u^^— ^ ~~~ rather than as a relative wishing to until ' all the paperwork is done.' George Shultz in Republic will not be allowed ' visit the country. On Christmas Day, The Observer home unless they are accompa- women when they arrived in the ports, which are awaiting their visit scared they are not touching us, preparation for a new city. to the British Embassy. Zana reassured her yesterday in a ' They told me to come back on informed the Foreign Office of the summit between Mikhail nied by their husbands. The young children of the When the sisters arrived in Taiz, telephone call . Tuesday with $500, three passport latest development in the women's Gorbachov and President Nadia and Zana-, Muhsen, who women — Nadia's daughter, 21- North Yemen's second city, they The official has also told Miss Ali, photographs and a return air situation. -

New Report Reveals Public Service Impact of Commercial Radio

May 16, 2011 NEW REPORT REVEALS PUBLIC SERVICE IMPACT OF COMMERCIAL RADIO RadioCentre, the industry body for commercial radio, today (May 16) released a new report, Action Stations: The Output and Impact of Commercial Radio, which highlights the industry’s investment in vital public service broadcasting such as news and information; cultural and social action; community involvement and charitable activities. The report is being backed by a nation-wide advertising campaign on commercial radio, highlighting the valuable contribution the industry makes to communities and local businesses. It follows on from commercial radio’s best–ever haul of 14 Golds at this year’s Sony Radio Academy Awards and record audience reach figures announced last week. The Action Stations report, which is the result of a substantial audit conducted across more than 160 commercial radio stations, shows that on average, some eight and a half hours of public service content are broadcast each week by commercial radio stations. Andrew Harrison, Chief Executive of RadioCentre said: “Commercial radio has been through some big changes in the last few years, with the launch of new national and regional brands offering a genuine alternative to the BBC. However, this report shows that is only part of the story. The vast majority of commercial stations are locally-focused and are still making a vital contribution to their communities by offering real public value. “Commercial radio achieved its biggest ever audience over the last quarter, with the potent combination of national networks and local services proving hugely successful in attracting listeners. This survey shows that these stations not only entertain, but also have a real impact on people’s lives.” The radio advertising campaign, which will be offered to all RadioCentre’s members, emphasises the importance of the stations’ relationships with their listeners, using the theme of ‘commercial radio, your radio’ to promote the notion and importance of a strong, thriving, local and regional commercial radio sector. -

The World According to Noddy: Life Lessons Learned in and out of Rock & Roll Pdf

FREE THE WORLD ACCORDING TO NODDY: LIFE LESSONS LEARNED IN AND OUT OF ROCK & ROLL PDF Noddy Holder | 256 pages | 01 Jul 2015 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781472119674 | English | London, United Kingdom Noddy Holder (Author of The World According To Noddy) What makes Noddy Holder tick? Told in his own inimitable style, Noddy shares insider accounts of. Told in his own inimitable style, Noddy shares insider accounts of his days on the road, along with a healthy dose of celebrity gossip, and leaves no stone unturned as he expounds on some of his favourite subjects — fame, friendship and fatherhood, the perils of social media and the modern age, not to mention what it would be like if he ruled the world. From his early days on The World According to Noddy: Life Lessons Learned in and Out of Rock & Roll West Midlands beat scene, including a stint as a roadie for Robert Plant, Noddy charts his rise from skinhead stomper to international pop-star, statesman, playboy, male model and philosopher, and of course one of the most integral parts of a Great British Christmas. Witty, wise and tremendously funny, this is Noddy Holder at his glittering best. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Told in his own inimitable style, Noddy shares insider accounts of What makes Noddy Holder tick? Get A Copy. -

Content-Based Recommendations for Radio Stations with Deep Learned Audio Fingerprints

Herausgeber et al. (Hrsg.): Informatik 2020, Lecture Notes in Informatics (LNI), Gesellschaft für Informatik, Bonn 2020 1 Content-based Recommendations for Radio Stations with Deep Learned Audio Fingerprints Stefan Langer ,1 Liza Obermeier ,2 André Ebert ,3 Markus Friedrich ,4 Emma Munisamy ,5 Claudia Linnhoff-Popien 6 Abstract: The world of linear radio broadcasting is characterized by a wide variety of stations and played content. That is why finding stations playing the preferred content is a tough task for a potential listener, especially due to the overwhelming number of offered choices. Here, recommender systems usually step in but existing content-based approaches rely on metadata and thus are constrained by the available data quality. Other approaches leverage user behavior data and thus do not exploit any domain-specific knowledge and are furthermore disadvantageous regarding privacy concerns. Therefore, we propose a new pipeline for the generation of audio-based radio station fingerprints relying on audio stream crawling and a Deep Autoencoder. We show that the proposed fingerprints are especially useful for characterizing radio stations by their audio content and thus are an excellent representation for meaningful and reliable radio station recommendations. Furthermore, the proposed modules are part of the HRADIO Communication Platform, which enables hybrid radio features to radio stations. It is released with a flexible open source license and enables especially small- and medium-sized businesses, to provide customized and high quality radio services to potential listeners. Keywords: Hybrid Radio, Multimedia Services, Recommender Systems, Unsupervised Learning, Deep Audio Fingerprints, Deep Learning 1 Introduction Despite emerging competition from on-demand content services, linear radio broadcasting still remains one of the most popular entertainment and information media in Europe. -

Craft Focus Magazine

www.craftfocus.com April/May 2010 April/May CRAFTFOCUS Issue 18 www.craftfocus.com MAGAZINE Happy Birthday Craft Focus! REVIEWS • Craft Hobby + Stitch International • CHA Winter Show TRIED AND TESTED KNITTING YARN How card making is evolving Does e-commerce work for your business? PLUS WIN! Latest products £500 worth of Numberjacks craft Industry profiles kits from Creativity International News & views Position Yourself for the Economic Recovery! Just turn the page to discover how leading UK retailers and manufacturers plan to grow their business in 2010! Give Your Business a Competitive Join us on a Special Reader Trip to the 27-29 Stephens Con Rosemont, Illinois - j “It’s the ideal platform for UK manufacturers and retailers to learn more about the US craft business and the way it operates. Many UK companies that have ventured into the important US market have used the Show as a starting point before committing full-scale.” - Sara Davies, Sales Director at Crafter’s Companion Discover Trends Before Your Competitors X Superb access to craft industry design, manufacturing and retail trends from across the globe X Engage with hundreds of exhibitors and thousands of attendees representing a vast selection of product categories across: B Scrapbooking and Papercrafts B Fabric, Quilting and Needlecrafts B Art Materials and Framing B General Crafts Edge and Find Inspiration in Chicago CHA 2010 Summer Convention & Trade Show July 2010 nvention Center just outside of Chicago Build Your Business with World Class Education X Business building seminars that provide attendees with ideas and strategies they can immediately apply to their own businesses. -

17 September 2010 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 11 SEPTEMBER 2010 Earlier This Year

Radio 4 Listings for 11 – 17 September 2010 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 11 SEPTEMBER 2010 earlier this year. She also chats to boaters who have made the people still did the foxtrot and the waltz to numbers such as 'Oh canal their home. Mike Clarke of the Leeds and Liverpool Johnny Oh,' played by the band. SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b00tn859) Canal Society tells Helen about the canal's history and about his The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. involvement with the Short Boat Kennet, one of the last Producer: Victoria Shepherd Followed by Weather. unconverted boats which worked on the Leeds & Liverpool A Juniper production for BBC Radio 4. Canal. Kennet is on the Register of Historic Vessels and serves as a reminder of the canal's heritage. SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b00tkyx7) SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (b00tn8t1) Storyteller: The Life of Roald Dahl Helen then joins Don Vine from the Yorkshire Wildlife Trust Elinor Goodman looks behind the scenes at Westminster as on a boat trip to an area between the canal and the River Aire Parliament returns for a two-week sitting before the main party Episode 5 where a special project is underway to improve the habitat for conferences. otters, before meeting up with John Fairweather at the unique 5 "Roald Dahl thought biographies were boring. He told me so Rise Lock at Bingley for an insight into life as a lock-keeper on while munching on a lobster claw." the longest canal in the UK. -

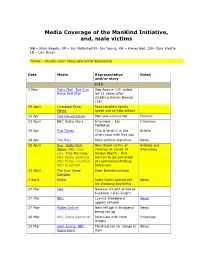

Media Coverage of the Mankind Initiative, And, Male Victims

Media Coverage of the ManKind Initiative, and, male victims MB – Mark Brooks, IM – Ian McNicholl,IY- Ian Young, KB – Kieron Bell, SW- Sara Westle LB – Lori Busch Yellow – denote court cases and initial disclosures Date Media Representative Detail and/or story 2018 3 May Daily Mail, The Sun, Zoe Adams (19) jailed News and Star for 11 years after stabbing Kieran Bewick (18) 29 April Liverpool Echo, Paul Lavelle’s family Metro speak out to help others 26 Apr The Conversation Men are victims too Feature 23 April BBC Radio Worc Interview – Ian Interview McNicholl 19 Apr The Times This is what it is like Article when your wife hits you 18 Apr The Sun Male victims statistics News 16 April Sun, Daily Mail, Alex Skeel victim of Articles and Metro, BBC Five violence at hands of interviews Live, This Morning, Jordan Worth - first BBC Radio Scotland, woman to be convicted BBC Three Counties, of coercive/controlling BBC Breakfast behaviour 13 April The Sun (Dear Dear Deirdre column Deirdre) 7 April Mirror Jodie Owen spared jail News for stabbing boyfriend 29 Mar Mail Nasreen Knight attacked husband Julian knight 27 Mar BBC Lavinia Woodward News appeal refused 27 Mar Wales Online New refuge in Bridgend News being set up 26 Mar BBC Radio Somerset Interview with Mark Interview Brooks 23 Mar Kent online, BBC ManKind call for refuge in News Radio Kent Kent 14-16 Mar Stoke Sentinel, BBC Pete Davegun fundraiser Radio Stoke, Crewe Guardian, Staffs Live 19 Mar Victoria Derbyshire Mark Brooks interview Interview 12 Mar Somerset Live ManKind Initiative appeal -

39 SUMMARY This Is a Summary of My Report. Fuller Analysis And

SUMMARY This is a summary of my Report. Fuller analysis and examples supporting my views are found in each chapter of the Report. SETTING UP THE REVIEW: THE TERMS OF REFERENCE (CHAPTER 1) 1. In early October 2012, the country was deeply shocked about revelations that Sir James Savile, the well-known and well-loved television personality and charity fundraiser had in fact been a prolific sex offender. Some of his offences were said to have taken place in connection with his work for the BBC. Later that month, I was invited by the BBC to investigate Savile’s sexual misconduct and the BBC’s awareness of it. The Review’s Terms of Reference (as amended) are that I should: receive evidence from those people who allege inappropriate sexual conduct by Jimmy Savile in connection with his work for the BBC, and from others who claim to have raised concerns about Jimmy Savile’s activities (whether formally or informally) within the BBC; (PART 1) investigate the extent to which BBC personnel were or ought to have been aware of inappropriate sexual conduct by Jimmy Savile in connection with his work for the BBC, and consider whether the culture and practices within the BBC during the years of Jimmy Savile’s employment enabled inappropriate sexual abuse to continue unchecked; (PART 2) in the light of findings of fact in respect of the above, identify the lessons to be learned from the evidence uncovered by the Review; (PART 3) 39 as necessary, take into account the findings of Dame Linda Dobbs in her investigation into the activities of Stuart Hall. -

RISHI SUNAK SARATHA RAJESWARAN a Portrait of Modern Britain Rishi Sunak Saratha Rajeswaran

A PORTRAIT OF MODERN BRITAIN RISHI SUNAK SARATHA RAJESWARAN A Portrait of Modern Britain Rishi Sunak Saratha Rajeswaran Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Registered charity no: 1096300. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Trustees Daniel Finkelstein (Chairman of the Board), Richard Ehrman (Deputy Chair), Theodore Agnew, Richard Briance, Simon Brocklebank-Fowler, Robin Edwards, Virginia Fraser, David Frum, Edward Heathcoat Amory, David Meller, Krishna Rao, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, Charles Stewart-Smith and Simon Wolfson About the Authors Rishi Sunak is Head of Policy Exchange’s new Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) Research Unit. Prior to joining Policy Exchange, Rishi worked for over a decade in business, co-founding a firm that invests in the UK and abroad. He is currently a director of Catamaran Ventures, a family-run firm, backing and serving on the boards of various British SMEs. He worked with the Los Angeles Fund for Public Education to use new technology to raise standards in schools. He is a Board Member of the Boys and Girls Club in Santa Monica, California and a Governor of the East London Science School, a new free school based in Newham.