A Study of the Internet and Connectivity in South American Countries to 2017: an Analytical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TABLE 7 - Trans-Ocean Fiber Optic Cable Capacity

TABLE 7 - Trans-Ocean Fiber Optic Cable Capacity Table 7 - Continued - Construction cost sources: Cable Source Trans - Atlantic - Operational: TAT-8 98 FCC 2 nd 447 (1984) PTAT 100 FCC 2 nd 1036 (1985) TAT-9 4 FCC Rcd 1130 (1989) TAT-10 7 FCC Rcd 445 (1992) TAT-11 7 FCC Rcd 136 (1992) TAT-12/13 8 FCC Rcd 4811 (1993) CANTAT-3 www.athens.actinc.bc.ca/ACT/news.oct/cable.html, downloaded 3/10/1997. Columbus II Application, filed on November 10, 1992, File No. ITC-93-029. CANUS-1 n.a. Atlantic Crossing (AC-1) www.submarinesystems.com/tssl/newswire/netherlands.htm, downloaded 12/15/99. Gemini www.cwplc.com/press/1996/p96oct28.htm, downloaded 6/18/1998. Columbus III www.att.com/press/0298/980211.cia.html, downloaded 7/1/1998. Level 3 www.simplextech.com/news/pr990511.html, downloaded 12/01/1999. TAT-14 www.francetelecomna.com/nr/nr_prre/nr_prre_9-2-98_tat.htm, downloaded 12/14/1999. FLAG Atlantic - 1 www.flagatlantic.com/gts_and_flag_131099.htm, downloaded 12/14/1999. Hibernia Atlantic (formerly 360atlantic) www.worldwidefiber.com/html/news_14july1999.html, downloaded 11/29/1999. Tyco Atlantic n.a. Apollo www.techweb.com/wire/story/TWB20010112S0004, downloaded 10/15/2003. Americas - Operational: Americas I Application, filed on November 10, 1992, File No. ITC-93-030 TCS-1 5 FCC Rcd 101 (1990) Taino-Carb 7 FCC Rcd 4275 (1992) BAHAMAS II n.a. Antillas I n.a. Pan American Cable System www.twoten.press.net/stories/headlines/BUSINESS_mci_Cable.html, downloaded 2/27/98. Americas II www.investors.tycoint.com/news/19980302-5261.htm, downloaded 12/15/1999. -

In This Issue: 11 Years All Optical Submarine Network Upgrades Of

66 n o v voice 2012 of the ISSn 1948-3031 Industry System Upgrades Edition In This Issue: 11 Years All Optical Submarine Network Upgrades of Upgrading Cables Systems? More Possibilities That You Originally Think Of! Excellence Reach, Reliability And Return On Investment: The 3R’s To Optimal Subsea Architecture Statistics Issue Issue Issue #64 Issue #3 #63 #2 Released Released Issue Released Released #65 Released 2 ISSN No. 1948-3031 PUBLISHER: Wayne Nielsen MANAGING EDITOR: Kevin G. Summers ovember in America is the month Forum brand which we will be rolling out we celebrate Thanksgiving. It during the course of the year, and which CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Stewart Ash, is also the month SubTel Forum we believe will further enhance your James Barton, Bertrand Clesca, Dr Herve Fevrier, N Stephen Jarvis, Brian Lavallée, Pete LeHardy, celebrates our anniversary of existence, utility and enjoyment. We’re going to kick Vinay Rathore, Dr. Joerg Schwartz that now being 11 years going strong. it up a level or two, and think you will like the developments . And as always, it will Submarine Telecoms Forum magazine is When Ted and I established our little be done at no cost to our readers. published bimonthly by Submarine Telecoms magazine in 2001, our hope was to get Forum, Inc., and is an independent commercial enough interest to keep it going for a We will do so with two key founding publication, serving as a freely accessible forum for professionals in industries connected while. We had a list of contacts, an AOL principles always in mind, which annually with submarine optical fiber technologies and email address and a song in our heart; the I reaffirm to you, our readers: techniques. -

Telxius Offers Managed Spectrum on Dunant and Marea Powered by Ciena

PRESS RELEASE Telxius offers managed spectrum on Dunant and Marea powered by Ciena Madrid, April 7th, 2021. Telxius, the leading neutral telecommunications infrastructure operator, has announced today the company will be collaborating with Ciena a networking systems, services and software company, to power two of the most modern transatlantic submarine cables, Marea and Dunant. With Ciena’s Spectrum Sharing submarine network infrastructure, Telxius is able to provide highly flexible managed spectrum service, offering customers tailored virtual fiber pairs suited to their needs. Marea and Dunant combined feature one of the lowest latency and highest capacity diverse routes globally. Dunant has recently been added to the Telxius portfolio to complete an unmatched transatlantic proposition in combination with Marea. Both cables will allow customers to benefit from Telxius’ extensive footprint, network capabilities and range of services. Directly connecting Ashburn, Richmond and Virginia Beach in the US to Paris, Madrid and Derio (Bilbao) in Europe, these two systems provide direct access to areas with the largest concentration of data centers in the world and key connectivity hubs. Telxius will be using Ciena’s GeoMesh Extreme submarine networking solution so as to better address the global connectivity needs of content providers, global enterprise and third-party operators. Important elements of the solution include Ciena’s 6500 Reconfigurable Line System (“RLS”) integrated C&L-band for scalable terrestrial backhaul, and WaveLogic 5 Extreme coherent optics that offer new levels of capacity and fiber efficiencies on Marea and Dunant. “Telxius is responding to the ever-increasing demand for low latency, high capacity transatlantic connectivity through ongoing network infrastructure expansion”, says Carlos Dasi, CTO of Telxius Cable. -

The Story of Subsea Telecommunications & Its

The Story of Subsea Telecommunications 02 & its Association with Enderby House By Stewart Ash INTRODUCTION The modern world of instant communications 1850 - 1950: the telegraph era began, not in the last couple of decades - but 1950 - 1986: the telephone era more than 160 years ago. Just over 150 years 1986 until today, and into the future: the optical era ago a Greenwich-based company was founded that became the dominant subsea cable system In the telegraph era, copper conductors could supplier of the telegraph era, and with its carry text only — usually short telegrams. During successors, helped to create the world we know the telephone era, technology had advanced today. enough for coaxial cables to carry up to 5,680 simultaneous telephone calls. And in today’s On 7 April 1864, the Telegraph Construction and optical era, fibres made of glass carry multi- Maintenance Company Ltd, better known for most wavelengths of laser light, providing terabits of of its life as Telcon, was incorporated and began its data for phone calls, text, internet pages, music, global communications revolution from a Thames- pictures and video. side site on the Greenwich Peninsula. Today, high capacity optic fibre subsea cables For more than 100 years, Telcon and its successors provide the arteries of the internet and are the were the world’s leading suppliers of subsea primary enablers of global electronic-commerce. telecommunications cable and, in 1950, dominated the global market, having manufactured and For over 160 years, the Greenwich peninsula has supplied 385,000 nautical miles (714,290km) of been at the heart of this technological revolution, cable, 82% of the total market. -

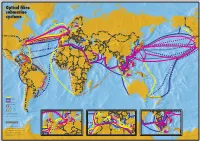

Optical Fibre Submarine Systems

Optical fibre submarine GREENLAND systems D N ALASKA A (USA) ICELAND L Umeå N Vestmannaeyjar BOTNIA I Vaasa F Faroes SWEDEN Rauma RUSSIA 6 x 622 Turku Hallstavik Whittier Valdez Karst 2 + 1 x 2.5 Gbit/s Norrtälje Kingisepp Seward Tallin NORWAY ESTONIA U N Lena I 2 x 560 LATVIA CANTAT-3 T point AC-1 E DENMARK CANADA D Westerland LITHUANIA Northstar 2 x 4 (WDM) x 2.5 Gbit/s TAT-14 K I N REP. OF IRELAND G BELORUSSIA TAT-10 2 + 1 x 560 D S D Norden/ N O LA Grossheide ER POLAND M TH NE GERMANY Gemini North 2 x 6 (WDM) x 2.5 Gbit/s BELGIUM CZECH Dieppe REP. Port UKRAINE Alberni NPC 3 + 1 x 420 St Brieuc SLOVAK REP. M O KAZAKHSTAN L FRANCE D Seattle AC-1 AUSTRIA A V TPC-5 2 x 5 Gbit/s HUNGARY I Tillamook PTAT-1 3 + 1 x 420 Gbit/s SWITZ. I A A Odessa DM) x 2.5 St Hilaire de Riez SLOVEN 2 x 6 (W MONGOLIA i South FLAG Atlantic-1 160 Gbit/s emin CROATIA ROMANIA Pacific G Y I U Novorossijsk City Pennant Point HERZEGOVINABOSNIA- G s T O 2.5 SochiGbit/s PC-1 Medway Harbour Gbit/ S x 5 L TAT-11 3 DxM 560) A Varna Shirley x 3 (W A V Nakhodka TAT-12 2 x 3 (WDM) x 5 Gbit/s 2 I GEORGIA Ishikati TAT-13 A BULGARIA UZBEKISTAN Rhode Island F L PC-1 L ALBANIA Poti A KYRGYZSTAN N Long Island G Y TAT-9 2 + 1 x 560 ARMENIA AZERBAIJAN New York MACEDONIA TURKMENISTAN NORTH Bandon TAT-8 2 x 280 Istanbul KOREA FLAG Atlantic-1 160 Gbit/s Azores SPAIN E R-J-K C 2 x 560 0 EE 6 R 5 G Dalian A CANUS-1 TAT-14 PORTUGAL TURKEY JIH CableProject Japan-US Manasquan Lisbon UNITED STATES 3x TAJIKISTAN Point Sesimbra PC-1 Arena Tuckerton Marmaris Yantaï SOUTH P TPC-4 2 x 560 A S -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE TELEFONICA SELLS TELXIUS TOWER DIVISION TO AMERICAN TOWERS CORPORATION AT RECORD MULTIPLES FOR 7.7 BILLION EUROS • The implied multiple of value over OBITDAaL proforma would be 30.5 times, if such number is adjusted to consider the full impact of the German portfolio acquired by Telxius in June 2020. • The deal is part of the strategy and fulfillment of the Telefónica Group's plan, which includes, among other objectives, an active portfolio management policy for its businesses and assets, based on value creation. • The agreement reached contemplates the maintenance of the current lease contracts of the towers and includes the maintenance of employment by American Towers Corporation (ATC). Madrid, January 13 2021.- Telefónica informs that, today, its subsidiary Telxius Telecom, S.A. (a company of the Telefónica Group minority-owned, directly or indirectly, by KKR and Pontegadea), has signed an agreement with American Tower Corporation ("ATC") for the sale of its telecommunications towers division in Europe (Spain and Germany) and in Latin America (Brazil, Peru, Chile and Argentina), for an amount of [7.7 billion euros], payable in cash. The agreement establishes the sale of a number of approximately [30,722] telecommunication tower sites and comprises two separate and independent transactions (on one hand, the Europe business and, on the other hand, the Latin American business), setting the respective closings once the corresponding regulatory authorizations have been obtained. Among other aspects, the sale agreement provides for a commitment to the employment by ATC. On the other hand, the Telefónica Group operators will maintain the current leases agreements of the towers signed with the companies sold subsidiaries of Telxius Telecom, S.A., so that these operators will continue to provide their services in similar terms to the current ones. -

KDDI Global ICT Brochure

https://global.kddi.com KDDI-Global Networks and IT Solutions Networking, Colocation, System Integration around the world BUILDING YOUR BUSINESS TOGETHER KDDI solutions are at the cutting-edge in all fields of information and communications KDDI, a Fortune Global 500 company, is one of Asia’s largest telecommunications providers, with approximately US$48 billion in annual revenue and a proven track record extending over many years and around the world. We deliver all-round services, from mobile phones to fixed-line communications, making us your one-stop solution provider for telecommunications and IT environments. The high praise and trust enjoyed by our TELEHOUSE data centers positioned around the world have kept us at the forefront of service and quality. Since our establishment in 1953, we have expanded our presence into 28 countries and 60 cities, with over 100 offices around the world supporting the success of our international customers through our high quality services. KDDI’s mobile telephone brand “au” has achieved significant market share in Japan, one of the world’s most comprehensive KDDI Quick Facts communications markets. KDDI’s relationship with over 600 carriers worldwide enables us to provide high-quality international network services in over 190 countries. Our exciting ventures, built on extensive experience, include investment in the “South-East Asia Japan 2 Cable”, which connects 11 locations in 9 countries and territories in Asia. Moreover, as the world moves toward the age of IoT and 5G, KDDI is taking steps to promote IoT business, such as connected cars, support for companies engaged in global business, and the creation of new value for our society. -

March 30, 2015 by ELECTRONIC FILING Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary Federal Communications Commission 445 12Th Street, S.W. Washin

(202) 223-7323 (202) 204-7371 [email protected] March 30, 2015 BY ELECTRONIC FILING Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20554 Re: Joint Application for Transfer of Control of Cable Landing Licenses from Columbus Networks, Limited to Cable & Wireless Communications Plc, File Nos. SCL-T/C-20141121-00013 and SCL-T/C-20141121-00014; Applications for Transfer of Control of Section 214 Authorizations from Columbus Networks, Limited to Cable & Wireless Communications Plc, File Nos. ITC-T/C-20141121-00304 and ITC-T/C-20141121-00307 Dear Ms. Dortch: On Thursday, March 26, 2015, the undersigned counsel and representatives of Cable & Wireless Communications Plc (“C&W”) and Columbus Networks, Limited (“CNL”) met with members of the Commission’s staff to discuss the above-cited pending applications, and in particular Digicel’s pleadings and ex parte filing in the proceeding. Doc#: US1:9949275v3 Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary 2 Attending this meeting on behalf of Cable & Wireless Communications Plc were Belinda Bradbury, General Counsel, and Simeon Irvine, Chief Executive, Wholesale. C&W outside counsel Patrick Campbell and Diane Gaylor of Paul,Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP also attended. Attending on behalf of Columbus Networks, Limited were Paul Scott, President and Chief Operating Officer, Columbus Networks USA, Inc., and Victor A. Lago, Vice President of Legal Affairs, Columbus Networks USA, Inc. CNL outside counsel Ulises Pin of Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP also attended. Commission staff in attendance were, from the International Bureau, Nese Guendelsberger, Deputy Bureau Chief (by phone); Kathleen Collins, Assistant Bureau Chief; Walt Strack, Assistant Bureau Chief and Chief Economist; Howard Griboff, Acting Division Chief, Policy Division; David Krech, Associate Division Chief, Policy Division; Mark Uretsky, Senior Economist, Policy Division; Jodi Cooper, Senior Attorney, Policy Division; and, from the Office of General Counsel, James Bird. -

T He Growing Noncommunicable Disease Burden, a Challenge for the Countries of the Americas1

FEATURE T HE GROWING NONCOMMUNICABLE DISEASE BURDEN, A CHALLENGE FOR THE COUNTRIES OF THE AMERICAS1 Jorge Litvak,2 his Ruiz,3 Helena E. Restrepo,3 and Alfred McAlister* Introduction Social and demographic trends in Western Hemisphere populations are introducing new challenges to public health. As sanitary conditions improve and population growth slows, health conditions change in a predictable pattern: the share of illnesses and deaths caused by infectious disease and perinatal difficulties declines, while the share caused by noncommunicable diseasesincreases. Life expectancy rises when premature deaths during infancy and childhood are prevented. But premature and pre- ventable deaths are not eradicated; they are merely shifted to later ages and different causes-including cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases,can- cers, accidents, liver disease, and diabetes. There is growing evidence that a significant proportion of these premature deaths, and even of new casesof illness among adults, can be prevented by inducing changes in the popula- tion’s life-style (I)-that is, by reducing smoking and alcohol abuse, by im- proving diets and increasing physical activity, by reducing obesity, and by making certain other changes in health services, safety practices, and envi- ronmental conditions (2). Consequently, the application of be- havioral sciencesin promoting healthier life-styles emerges as the next great ’ This ankle will also be published in Spanish in the Bob% de la Ojkitia Sanitaria Panamenkana. 2 Program Coordinator, Health of Adults Program, Pan American Health Organization, Washington, D.C., USA. 3 Regional Adviser in Chronic Diseases, Health of Adults Program, Pan American Health Organization, Washington, D.C., USA. 4 Associate Director for Community Studies; Center for Health Promotion, Research. -

2013 Submarine Cable Market Industry Report

submarine telecoms INDUSTRY REPORT 2013 Authored by Submarine Cable Industry Report Issue 2 March 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Submarine Telecoms Forum, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Submarine Telecoms Forum, Inc. 21495 Ridgetop Circle Suite 201 Sterling, Virginia 20166 USA www.subtelforum.com ISSN: pending 2 Disclaimer: While every care is taken in preparation of this publication, the publishers cannot be held responsible for the accuracy of the information herein, or any errors which may occur in advertising or editorial content, or any consequence arising from any errors or omissions, and the editor reserves the right to edit any advertising or editorial material submitted for publication. If you have a suggestion, please let us know by emailing [email protected]. 3 Table of Contents 1. Foreword 10 2. Introduction 11 3. Executive Summary 13 4. Worldwide Market Analysis and Outlook 18 4.1 Overview of Historical System Investment 20 4.2 2008 – 2012 Systems in Review 20 4.3 Systems Investment in 2013 and Beyond 21 5. Supplier Analysis 25 5.1 System Suppliers 25 5.2 Upgrade Suppliers 26 6. Ownership Analysis 28 6.1 Financing of Current Submarine Systems 28 7. Regional Market Analysis and Capacity Outlook 31 7.1 Transatlantic -

Geolab Ellalink

GA collaborative innovation that uses telecom subsea infrastruc- tures to help scientists in their understanding of our planet. White Paper The seabed is often seen as a place that is not subject to change. However, it is subject to constant change caused by a variety of factors. Some changes are caused by interac- Subsea telecoms cables: tions between the ocean and the seabed, while longer-term changes occur far below A driver for scientific research the surface, in the crust of our planet. Because more than 70% of the earth’s surface is covered by water, research is very difficult to perform. Traditionally, research in sub-sea regions has only been possible Chris Atherton - Senior Research Engagement Officer - GÉANT using large research vessels or sensors tethered by very expensive dedicated cable sys- Auke Pals - Project Manager - GÉANT tems usually limited to near-coastal installations. This limits the ability of the scientific community to investigate what is happening in our Oceans on a broad scale. Dr Mohammad Belal - National Oceanography Centre - GFZ Angello Strollo - Member of Executive Committee of ORFEUS. Head of GEOFON - service of the GFZ The EllaLink cable that is being deployed across the Atlantic, between Portugal and Frederik Tilmann - Member of Board of Directors of ORFEUS Brazil, has opened up an opportunity to integrate a scientific component into a com- mercial submarine cable system. GeoLab was created as a partnership between EllaLink, Introduction EMACOM, FCT, and GÉANT to provide an infrastructure for the benefit of the global scientific community. « Two thirds of the surface of our planet are covered by water and are still poorly instru- mented, which has prevented the earth science community from addressing numerous This infrastructure consists of a spare fibre pair built into the Funchal branch of the key scientific questions. -

The Hidden Meaning in Those Letters and Numbers

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 2 No. 19 [Special Issue – October 2012] The Hidden Meaning in Those Letters and Numbers Chuck Higgins, Ph.D. Dept. Finance/CIS Loyola Marymount Univ. 1 LMU Drive Los Angeles, CA 90045-8385 USA We all find number and letter codes around us. Many of these are both relevant and often easy to decode. Included herein are those most of us encounter: airport/ airline/airplane codes, alphabets, bonds, Braille, broadcast call letters, radio AM/FM, television, checks, corporations, credit cards, dates, highways, internet, license plates, measures, money, numbers, postal codes, postage stamps, railroads/trains, ships/boats, Social Security, stocks, telephone, temperature, time, and universal product codes. Not included herein are those that are field specific or important only to specialists. Thus not included are codes found in science, technology, special fields, and commerce; examples excluded include chemistry and physics, model numbers, ham radio and hobbies, expiration dates, and so on. All graphics herein are from Wikipedia or are mine. Thank you to Michelle Yeung and Zbigniew Przasnyski for their suggestions. Airports/Airlines/Airplanes ABC Airport codes are three letter mnemonics (four letters instead for pilots), some with historic references (ORD for O’Hare Airport previously called Orchard Field and MSY for New Orleans’ Moisant Field); see www.skygod.com for a full history. In the U.S. there are rarely airport codes starting with K, N, or W. The codes for Canadian airports usually start with a Y, but the reverse may not be true (YUM for Yuma International for example). A recommended website for flights is www.airfare.com .