Space and Time, Measured by the Heart: Memory and the Music of Stuart Saunders Smith in Composing, Many Try to Be Consiste

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: DOI: 10.7766/Orbit.V1.1.30

Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon https://www.pynchon.net ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): Erik Ketzan Affiliation(s): Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Mannheim, Germany Title: Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/30 DOI: 10.7766/orbit.v1.1.30 Abstract: This paper argues that Pynchon may allude to Marcel Proust through the character Marcel in Part 4 of Gravity's Rainbow and, if so, what that could mean. I trace the textual clues that relate to Proust and analyze what Pynchon may be saying about a fellow great experimental writer. Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Erik Ketzan Editorial note: a previous draft of this paper appeared on The Modern Word in 2010. Remember the "Floundering Four" part in Gravity's Rainbow? It's a short story of sorts that takes place in a city of the future called Raketen-Stadt (German for "Rocket City") and features a cast of comic book-style super heroes called the Floundering Four. One of them is named Marcel, and I submit that he is meant as some kind of representation of the great Marcel Proust. Only eight pages long, the Floundering Four section is a parody/riff on a sci-fi comic book story, loosely patterned on The Fantastic Four by Marvel Comics. It appears near the end of Gravity's Rainbow among a set of thirteen chapterettes, each one a fragmentary "text". As Pynchon scholar Steven Weisenburger explains, "A variety of discourses, modes and forms are parodied in the… subsections.. -

Jonathan Greenberg

Losing Track of Time Jonathan Greenberg Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation tells a story of doing nothing; it is an antinovel whose heroine attempts to sleep for a year in order to lose track of time. This desire to lose track of time constitutes a refusal of plot, a satiric and passive- aggressive rejection of the kinds of narrative sequences that novels typically employ but that, Moshfegh implies, offer nothing but accommodation to an unhealthy late capitalist society. Yet the effort to stifle plot is revealed, paradoxically, as an ambi- tion to be achieved through plot, and so in resisting what novels do, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends up showing us what novels do. Being an antinovel turns out to be just another way of being a novel; in seeking to lose track of time, the novel at- tunes us to our being in time. Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed.1 For a long time I used to go to bed early.2 he first of these sentences begins Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2018 novelMy Year of Rest and Relaxation; the second, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. More ac- T curately, the second sentence begins C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Proust, whose French reads, “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” D. J. Enright emends the translation to “I would go to bed”; Lydia Davis and Google Translate opt for “I went to bed.” What the translators famously wrestle with is how to render Proust’s ungrammatical combination of the completed action of the passé composé (“went to bed”) with a modifier (“long time”) that implies a re- peated, habitual, or everyday action. -

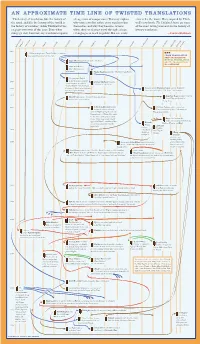

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE of TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The History of Translation, Like the History of a Long Series of Compromises

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE OF TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The history of translation, like the history of a long series of compromises. This may explain error is for the worse. Here, inspired by Thirl- the novel, and like the history of the world, is why some novelists refuse every translator but well’s new book, The Delighted States, are some the history of mistakes,” Adam Thirlwell writes themselves, and why they become anxious of the most vexing moments in the history of on page seventeen of this issue. Even when when their work must travel through a chain literary translation. things go well, however, any translation requires of languages to reach its public. But not every —Jascha Hoffman E N S E A N H I H H N N U N H H A C A S H S I C S A A H G A S I S N L I H H I I C I I I I B B L M S U D A A T C C N N S I T S N D U B A T G E R L S E R T L E N R R A D L R A E Z U N I R E E O O U P W I O A A C C C D E F F G P P P R S S Y Y 1490 KEY: A Valencian knight writes Tirant Lo Blanc in Catalan. CHAIN TRANSLATION It is finished by a friend after his death. SELF TRANSLATION Edgar Allan Poe publishes his poem “The Raven.” MUTUAL TRANSLATION 1850 GROUP TRANSLATION NO CATEGORY Lewis Carroll writes Alice’s Adventures in W onderland. -

CLAUDIA BAEZ Paintings After Proust

ART 3 109 Ingraham Street T 646 331 3162 Brooklyn NY 11237 www.art-3gallery.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST Curated by Anne Strauss October 8 – November 22, 2014 Opening: Wednesday, October 8, 6 - 9 PM Claudia Baez, PAINTINGS after PROUST “And as she played, of all Albertine’s multiple tresses I could see but a single heart-shaped loop of black hair dinging to the side of her ear like the bow of a Velasquez Infanta.”, 2014, oil on canvas, 18 x 24 in. (45.7 x 61 cm.) © Claudia Baez Courtesy of ART 3 gallery Brooklyn, NY, September 19, 2014 – ART 3 opened in Bushwick in May 2014 near Luhring Augustine with its Inaugural Exhibition covered by The New York Times T Magazine, Primer. ART 3 was created by Silas Shabelewska-von Morisse, formerly of Haunch of Venison and Helly Nahmad Gallery. In July 2014, Monika Fabijanska, former Director of the Polish Cultural Institute in New York, joined ART 3 as Co-Director in charge of curatorial program, museums and institutions. ART 3 presents CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST on view at ART 3 gallery, 109 Ingraham Street, Bushwick, Brooklyn, from October 8 to November 22, 2014, Tue-Sat 12-6 PM. The opening will take place on Wednesday, October 8, from 6-9 PM. “In PAINTINGS after PROUST, Baez offers us an innovative chapter in contemporary painting in ciphering her art via a modernist work of literature within a postmodernist framework. […] In Claudia Baez’s exhibition literary narrative is poetically refracted through painting and vice versa, which the painter reminds us with artistic verve and aplomb of the adage that every picture tells a story as well as the other way around”. -

Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust. John Stephen Larose Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Larose, John Stephen, "Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7206. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7206 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

An Obsession with Time in Selected Works of T

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 52 (2016) 207-215 EISSN 2392-2192 An Obsession with Time in Selected Works of T. S. Eliot as a Major Modernist Ensieh Shabanirad1,*, Ronak Ahmady Ahangar2 1Department of English Language and Literature, University of Tehran, Iran 2Department of English Language and Literature, University of Semnan, Iran *E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT As a poet, Eliot seems obsessed with time: the speaker of "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" keeps worrying about being late, and the passage of time in general as he gets older seems to continuously haunt him. In "The Waste Land" we have another form of obsession that presents itself in form of intertexuality; the many narrators of the poem go back and forth in time and provide almost random recollections of the past or haphazard bits of literary texts that are equally concerned with time. This article aims to look deeper into the importance of the concept time in Eliot's poetry, the two poems already mentioned as well as "Four Quartets" (in which a whole section is devoted to time and its philosophy) and then take the important works of other key figures of Modernism and the movement's characteristics into comparison in order to determine whether Eliot's seeming obsession is a fruit of its era or a personal motif of the poet. Keywords: T. S. Eliot; Concept of Time; Intertextuality; Modernist Poetry 1. INTRODUCTION T. S. Eliot is the well known leading figure of the Modernism movement and winner of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1948. -

New York University

New York University Spring 2020 CORE-UA 761 EXPRESSIVE CULTURES LA BELLE ÉPOQUE: PAINTING, MUSIC AND LITERATURE IN FRANCE 1852-1914 TUESDAY, THURSDAY 11-12.15 Cantor 101 Professor Thomas Ertman ([email protected]) This course takes as its subject the Belle Époque, that period in the life of France’s pre-World War I Third Republic (1871-1914) associated with extraordinary artistic achievement, as well as the Second Empire (1851-1871) that preceded it. Not only was Paris during this time the undisputed western capital of painting and sculpture, it also was the most important production site for new works of musical theater and, arguably, literature as well. It was during these decades that Impressionism launched its assault on the academic establishment, only to be superseded itself by an ever-changing avant-garde associated first with the Nabis, then with fauvism and cubism; that the operas of Bizet, Saint-Saëns and Massenet and the plays of Sardou and Rostand filled the world’s theaters; and that the novels of Zola and stories of Maupassant were translated into dozens of languages. Finally, this was the society that gave birth to one of the greatest literary works of all time, Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the first volume of which appeared just as World War I was about to bring the Belle Époque to a violent end. In this course, we will attempt to gain a deeper understanding of the artistic works of this era by placing them in the context of the society within which they were produced, France’s Second Empire and Third Republic. -

Time Regained Proust, Marcel (Translator: Stephen Hudson)

Time Regained Proust, Marcel (Translator: Stephen Hudson) Published: 1931 Type(s): Novels, Romance Source: http://gutenberg.net.au 1 About Proust: Proust was born in Auteuil (the southern sector of Paris's then-rustic 16th arrondissement) at the home of his great-uncle, two months after the Treaty of Frankfurt formally ended the Franco-Prussian War. His birth took place during the violence that surrounded the suppression of the Paris Commune, and his childhood corresponds with the consolida- tion of the French Third Republic. Much of Remembrance of Things Past concerns the vast changes, most particularly the decline of the aristo- cracy and the rise of the middle classes, that occurred in France during the Third Republic and the fin de siècle. Proust's father, Achille Adrien Proust, was a famous doctor and epidemiologist, responsible for study- ing and attempting to remedy the causes and movements of cholera through Europe and Asia; he was the author of many articles and books on medicine and hygiene. Proust's mother, Jeanne Clémence Weil, was the daughter of a rich and cultured Jewish family. Her father was a banker. She was highly literate and well-read. Her letters demonstrate a well-developed sense of humour, and her command of English was suf- ficient for her to provide the necessary impetus to her son's later at- tempts to translate John Ruskin. By the age of nine, Proust had had his first serious asthma attack, and thereafter he was considered by himself, his family and his friends as a sickly child. Proust spent long holidays in the village of Illiers. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time I: Swann’s Way,trans. C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin, rev. by D.J. Enright (London: Vintage, 2002), p. 43. 2. Ibid. 3. Ibid. 4. Ibid., p. 44. 5. For an account of sexual perversions in the pre-modern, pre- sexological era, see, for example, Julie Peakman, ‘Sexual Perver- sion in History: An Introduction’, in Julie Peakman (ed.), Sexual Perversions, 1670–1890 (New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), pp. 1–49, and other essays in that collection. 6. Michel Foucault, The Will to Knowledge: The History of Sexuality Volume 1, trans. Robert Hurley (London: Penguin, 1998). 7. Roger Griffin, Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), pp. 45–6. 8. Anthony Giddens, The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies (Cambridge: Polity, 1992). 9. Cf. Richard G. Olson, Science and Scientism in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Urbana, IL and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2008), p. 294. 10. Cf. ibid., pp. 294 and 301–2. 11. Cf. Griffin, Modernism and Fascism, p. 90. 12. Max Nordau, Degeneration, trans. George L. Mosse (Lincoln, NE and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), p. 536. 13. Ibid., p. v. 14. Cf. Vernon A. Rosario, The Erotic Imagination: French Histories of Perversity (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 88. 15. Ibid., p. 40. 16. Thomas W. Laqueur, Solitary Sex: A Cultural History of Masturba- tion (New York: Zone Books, 2003), p. 278. 17. Griffin, Modernism and Fascism, p. -

Syllabus 470-643 Frankschool Fall 2015

The Frankfurt School and Its Writers Fall 2015, Rutgers University Prof. Nicholas Rennie German 16:470:643:01 [index 19121]/Comparative O. hrs. Tu 9:45am, Th 2:30pm, Literature 16:195:617:01 [index 10747] & by appointment Tuesdays 4:30-7:10pm, GH-102, 172 College Ave 172 College Ave., rm. 201A (CAC) Tel. 732-932-7201 [email protected] Work of the Frankfurt School is among the most important 20th-century German-language contributions to such fields as sociology, political science, gender studies, film, cultural studies and comparative literature. We will read texts by such key figures of the Frankfurt School as Walter Benjamin, Theodor W. Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse and Jürgen Habermas for their relevance to a number of disciplines, but give particular consideration to literary and aesthetic questions. To this end, we will also read texts by select authors to whom these figures responded (e.g. Baudelaire, Proust, Kafka, Beckett). Throughout the course, moreover, we will be examining responses to and development of the thought of the first and second generation of the Frankfurt School in more recent strands of Marxism, deconstruction, feminism, aesthetics and cultural studies. Requirements: 1) Weekly attendance and active participation in class discussion. 2) One 20-minute presentation, which may be the basis for one of the papers. 3) Three short papers totaling 16 pp. (see due dates below), or one 16-page paper (due Tuesday 12/15/15). Students who wish to write a single 16-page paper need to receive approval from me before the end of September. -

Perspectives in Time: Using the Arts to Teach Proust and His World Janet Moser Brooklyn College, City University of New York, U.S.A

International Journal of Education & the Arts Editors Liora Bresler University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, U.S.A. Margaret Macintyre Latta University of Nebraska-Lincoln, U.S.A. http://www.ijea.org/ ISSN 1529-8094 Volume 10 Portrayal 1 September 26, 2009 Perspectives in Time: Using the Arts to Teach Proust and His World Janet Moser Brooklyn College, City University of New York, U.S.A. Citation: Moser, J. (2009). Perspectives in time: Using the Arts to teach Proust and his world. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 10(Portrayal 1). Retrieved [date] from http://www.ijea.org/v10p1/. Abstract Arts resources available on the Internet and DVDs provide a flexible, richly resonant, student-friendly framework for a coordinated study of the connections between the style and structure of Proust’s novel and the social and cultural worlds he depicts. In Search of Lost Time, a product of an artistic revolution as well as a critical and historical contemplation of the question of how this revolution came about, looks back towards the arts of previous generations, compelling its readers to adopt a multitude of approaches in order to move forward into the Proustian world. A deeper, more intimate understanding of the world of the Search can be achieved in any classroom anywhere by integrating carefully selected electronic resources for film, architecture, painting, music, costume, decor and dance with the teaching of the written text. In particular, perspective in contemporary painting as a model for Proust’s innovations in narrative plays an important role in this study. IJEA Vol. 10 Portrayal 1 - http://www.ijea.org/v10p1/ 2 Introduction Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, a product of an artistic revolution as well as a critical and historical contemplation of the question of how this revolution came about, looks back towards the arts of previous generations, compelling its readers to adopt a multitude of approaches in order to move forward into the Proustian world. -

A Year United in Fragmentation: an Examination Into the History Of

A Year United in Fragmentation: An Examination into the History of Modernist Aesthetics and their Culmination in 1922 Dallas Bullard Undergraduate Departmental Honors Thesis for English Literature Committee: Dr. Bruce F. Kawin (ENGL), Dr. Cathy L. Preston (ENGL), Dr. Rimgaila Salys (GSLL) Advisor: Dr. Bruce F. Kawin April 2012 Acknowledgements I would like to extend a special thanks to Bruce Kawin for encouraging me to undertake this thoroughly intimidating project and for his assistance in all related matters. Additionally, I'd like to thank the other members of committee for their interest and participation. I also owe a great deal to Gleb Mordovskoi for his work that involved the translation of the Russian intertitles of Kino-pravda, some Russian words/phrases in Dziga Vertov's writings, and the French dialogue of Abel Gance: hier et demain . Finally, I extend my sincerest thanks to my parents for urging me to approach my academic studies with passion and diligence. Abstract When I was first introduced to Abel Gance's La Roue , I was rather interested in the fact that it was released in 1922. I knew that this was also the year that James Joyce's Ulysses and T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land were published. I began to wonder why this year produced such significant works of modernism. I repeatedly asked a professor of mine, Bruce Kawin, a number of questions about 1922. My core questions were: "Why then?" and "What happened before?" At some point, Professor Kawin suggested that I write an honors thesis on 1922. After some discussion about what the thesis should contain, I decided that I was interested in the history of modernist aesthetics.