English Or German, There Are Far Fewer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commune Correspondant Sécurité Routière Élu

Annexe 5 : Tableau des référents sécurité routière au sein des communes du Val-De-Marne (version du 01/03/2014) Commune Correspondant Sécurité Routière Élu Correspondant Sécurité Routière Technique Nom – Prénom LE CHENIC Stéphane Fonction Maire Adjoint Directeur Services Techniques Ablon-Sur-Seine Adresse 16, rue du Maréchal Foch 94480 Ablon-sur-Seine 16, rue du Maréchal Foch 94480 Ablon-sur-Seine Mél [email protected] [email protected] Tél 01 49 61 33 61 01 49 61 33 55 Nom – Prénom TUDELA Samuel VOITUS Raymond Fonction Conseiller Municipal chargé de la Circulation et du Stationnement Responsable du Service Domaine Public et Stationnement Alfortville Adresse Place François Mitterand 94140 Alfortville Place François Mitterand 94140 Alfortville Mél [email protected] [email protected] Tél 01 58 73 29 00 01 78 68 22 21 Nom – Prénom RANSAY Christiane GOMOT Pascal Fonction Adjointe au Maire Cadre de Vie Travaux Espaces Verts Artisanat Responsable du Service Cadre de Vie Arcueil Adresse 10 avenue Paul Doumer 94110 Arcueil 10 avenue Paul Doumer 94110 Arcueil Mél [email protected] [email protected] Tél 01 46 15 09 21 01 82 01 20 10 Nom – Prénom VADIVELOU Déva POLISSET Dominique Adjoint au Maire Prévention et Sécurité, Accessibilité Handicapés, Fonction Chef de Service Politique de la Ville / Prévention sécurité Arrêtés de circulation et Autorisation de voirie Adresse 7 boulevard Léon Révillon 94470 Boissy-Saint-Léger Rue Gaston Roulleau 94470 Boissy-Saint-Léger Mél [email protected] [email protected] Boissy-Saint-Léger Tél 01 45 10 61 61 01 45 69 02 70 Nom – Prénom THENAULT Fabien Fonction Responsable Voirie Adresse 3 rue de la Pompadour Zone d’activités de la Haie Griselle 94470 Boissy-Saint-Léger Mél [email protected] Tél 01 45 10 23 83 Nom – Prénom MAURIN André BOUSBAA Malika Fonction Maire-Adjoint Police Municipale Bonneuil-Sur-Marne Adresse 7, rue d'Estienne d'Orves 94380 Bonneuil-sur-Marne 17 av. -

National Council on the Humanities Minutes, No. 11-15

Office of th8 General Counsel N ational Foundation on the Aria and the Humanities MINUTES OF THE ELEVENTH MEETING OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE HUMANITIES Held Monday and Tuesday, February 17-18, 1969 U. S. Department of State Washington, D. C. Members present; Barnaby C. Keeney, Chairman Henry Haskell Jacob Avshalomov Mathilde Krim Edmund F. Ball Henry Allen Moe Robert T. Bower James Wm. Morgan *Germaine Br&e Ieoh Ming Pei Gerald F. Else Emmette W. Redford Emily Genauer Robert Ward Allan A. Glatthorn Alfred Wilhelmi Members absent: Kenneth B. Clark Charles E. Odegaard John M. Ehle Walter J. Ong Paul G. Horgan Eugene B. Power Albert William Levi John P. Roche Soia Mentschikoff Stephen J. Wright James Cuff O'Brien *Present Monday only - 2 - Guests present: *Mr. Harold Arberg, director, Arts and Humanities Program, U. S. Office of Education Dr. William Emerson, assistant to the president, Hollins College, Virginia Staff members present; Dr. James H. Blessing, director, Division of Fellowships and Stipends, and acting director, Division of Research and Publication, National Endowment for the Humanities Dr. S. Sydney Bradford, program officer, Division of Research and Publication, NEH Miss Kathleen Brady, director, Office of Grants, NEH Mr. C. Jack Conyers, director, Office of Planning and Analysis, NEH Mr. Wallace B. Edgerton, deputy chairman, NEH Mr. Gerald George, special assistant to the chairman, NEH Dr. Richard Hedrich, Director of Public Programs, NEH Dr. Herbert McArthur, Director of Education Programs, NEH Miss Nancy McCall, research assistant, Office of Planning and Analysis, NEH Mr. Richard McCarthy, assistant to the director, Office of Planning and Analysis, NEH Miss Laura Olson, Public Information Officer, NEH Dr. -

Fonds Gabriel Deville (Xviie-Xxe Siècles)

Fonds Gabriel Deville (XVIIe-XXe siècles) Répertoire numérique détaillé de la sous-série 51 AP (51AP/1-51AP/9) (auteur inconnu), révisé par Ariane Ducrot et par Stéphane Le Flohic en 1997 - 2008 Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 1955 - 2008 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_001830 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé en 2012 par l'entreprise Numen dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales 2 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Référence 51AP/1-51AP/9 Niveau de description fonds Intitulé Fonds Gabriel Deville Date(s) extrême(s) XVIIe-XXe siècles Nom du producteur • Deville, Gabriel (1854-1940) • Doumergue, Gaston (1863-1937) Importance matérielle et support 9 cartons (51 AP 1-9) ; 1,20 mètre linéaire. Localisation physique Pierrefitte Conditions d'accès Consultation libre, sous réserve du règlement de la salle de lecture des Archives nationales. DESCRIPTION Type de classement 51AP/1-6. Collection d'autographes classée suivant la qualité du signataire : chefs d'État, gouvernants français depuis la Restauration, hommes politiques français et étrangers, écrivains, diplomates, officiers, savants, médecins, artistes, femmes. XVIIIe-XXe siècles. 51AP/7-8. Documents divers sur Puydarieux et le département des Haute-Pyrénées. XVIIe-XXe siècles. 51AP/8 (suite). Documentation sur la Première Guerre mondiale. 1914-1919. 51AP/9. Papiers privés ; notes de travail ; rapports sur les archives de la Marine et les bibliothèques publiques ; écrits et documentation sur les départements français de la Révolution (Mont-Tonnerre, Rhin-et-Moselle, Roer et Sarre) ; manuscrit d'une « Chronologie générale avant notre ère ». -

Guidep J Web.Pdf

PARCS & JARDINS www.reims.fr , au fil de l ,eau Editorial page 5 Reims, ville verte, ville fleurie, offre avec près de 300 ha d’espaces de verdure une grande diversité de parcs et jardins. Des jardins historiques aux grands parcs, des bords de Vesle ou du canal aux espaces de proximité ce sont autant de lieux propices Sites à la promenade, à la rêverie ou aux activités physiques de plein air. et Les arbres, les arbustes et les fleurs qui parcourent monumentspage 8 nos rues et nos parcs offre nt un décor végétal aux quatre saisons. La Ville a aussi le souci de préserver l’environnement en recourant à des méthodes respectueuses pour l’entretien de ses espaces. Les grands Le label « 4 fleurs » attribué à la Ville de Reims témoigne espaces ainsi de toutes ces actions en faveur de la qualité du cadre de vie. page 18 Je vous invite à parcourir notre ville et découvrir à travers ce guide la richesse de notre patrimoine vert , de cette nature au cœur de la cité indispensable au bien-être de ses habitants. Au cœur Arnaud ROBINET des Député - Maire de Reims quartiers page 25 3 Parc des anciens bains des Trois Rivières 2,1 ha Espace de promenades, entre la Vesle et le canal, aménagé à proximité Légendes des anciens bains des Trois Rivières dont on peut voir les installations. Cet espace arboré relie par le biais de passerelles piétonnes, les bords de la rivière et du canal et constitue un des maillons de la coulée verte. La promenade longe des secteurs de jardins familiaux. -

Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: DOI: 10.7766/Orbit.V1.1.30

Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon https://www.pynchon.net ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): Erik Ketzan Affiliation(s): Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Mannheim, Germany Title: Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/30 DOI: 10.7766/orbit.v1.1.30 Abstract: This paper argues that Pynchon may allude to Marcel Proust through the character Marcel in Part 4 of Gravity's Rainbow and, if so, what that could mean. I trace the textual clues that relate to Proust and analyze what Pynchon may be saying about a fellow great experimental writer. Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Erik Ketzan Editorial note: a previous draft of this paper appeared on The Modern Word in 2010. Remember the "Floundering Four" part in Gravity's Rainbow? It's a short story of sorts that takes place in a city of the future called Raketen-Stadt (German for "Rocket City") and features a cast of comic book-style super heroes called the Floundering Four. One of them is named Marcel, and I submit that he is meant as some kind of representation of the great Marcel Proust. Only eight pages long, the Floundering Four section is a parody/riff on a sci-fi comic book story, loosely patterned on The Fantastic Four by Marvel Comics. It appears near the end of Gravity's Rainbow among a set of thirteen chapterettes, each one a fragmentary "text". As Pynchon scholar Steven Weisenburger explains, "A variety of discourses, modes and forms are parodied in the… subsections.. -

Jonathan Greenberg

Losing Track of Time Jonathan Greenberg Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation tells a story of doing nothing; it is an antinovel whose heroine attempts to sleep for a year in order to lose track of time. This desire to lose track of time constitutes a refusal of plot, a satiric and passive- aggressive rejection of the kinds of narrative sequences that novels typically employ but that, Moshfegh implies, offer nothing but accommodation to an unhealthy late capitalist society. Yet the effort to stifle plot is revealed, paradoxically, as an ambi- tion to be achieved through plot, and so in resisting what novels do, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends up showing us what novels do. Being an antinovel turns out to be just another way of being a novel; in seeking to lose track of time, the novel at- tunes us to our being in time. Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed.1 For a long time I used to go to bed early.2 he first of these sentences begins Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2018 novelMy Year of Rest and Relaxation; the second, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. More ac- T curately, the second sentence begins C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Proust, whose French reads, “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” D. J. Enright emends the translation to “I would go to bed”; Lydia Davis and Google Translate opt for “I went to bed.” What the translators famously wrestle with is how to render Proust’s ungrammatical combination of the completed action of the passé composé (“went to bed”) with a modifier (“long time”) that implies a re- peated, habitual, or everyday action. -

A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2014 The ubiC st's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Geoffrey David, "The ubC ist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 584. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTRE: A STYISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912. by Geoffrey David Schwartz A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2014 ABSTRACT THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTE: A STYLISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912 by Geoffrey David Schwartz The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Kenneth Bendiner This thesis examines the stylistic and contextual significance of five Cubist cityscape pictures by Juan Gris from 1911 to 1912. These drawn and painted cityscapes depict specific views near Gris’ Bateau-Lavoir residence in Place Ravignan. Place Ravignan was a small square located off of rue Ravignan that became a central gathering space for local artists and laborers living in neighboring tenements. -

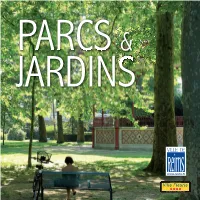

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE of TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The History of Translation, Like the History of a Long Series of Compromises

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE OF TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The history of translation, like the history of a long series of compromises. This may explain error is for the worse. Here, inspired by Thirl- the novel, and like the history of the world, is why some novelists refuse every translator but well’s new book, The Delighted States, are some the history of mistakes,” Adam Thirlwell writes themselves, and why they become anxious of the most vexing moments in the history of on page seventeen of this issue. Even when when their work must travel through a chain literary translation. things go well, however, any translation requires of languages to reach its public. But not every —Jascha Hoffman E N S E A N H I H H N N U N H H A C A S H S I C S A A H G A S I S N L I H H I I C I I I I B B L M S U D A A T C C N N S I T S N D U B A T G E R L S E R T L E N R R A D L R A E Z U N I R E E O O U P W I O A A C C C D E F F G P P P R S S Y Y 1490 KEY: A Valencian knight writes Tirant Lo Blanc in Catalan. CHAIN TRANSLATION It is finished by a friend after his death. SELF TRANSLATION Edgar Allan Poe publishes his poem “The Raven.” MUTUAL TRANSLATION 1850 GROUP TRANSLATION NO CATEGORY Lewis Carroll writes Alice’s Adventures in W onderland. -

Futurism-Anthology.Pdf

FUTURISM FUTURISM AN ANTHOLOGY Edited by Lawrence Rainey Christine Poggi Laura Wittman Yale University Press New Haven & London Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College. Frontispiece on page ii is a detail of fig. 35. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Scala type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Futurism : an anthology / edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-08875-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Futurism (Art) 2. Futurism (Literary movement) 3. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Rainey, Lawrence S. II. Poggi, Christine, 1953– III. Wittman, Laura. NX456.5.F8F87 2009 700'.4114—dc22 2009007811 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: F. T. Marinetti and the Development of Futurism Lawrence Rainey 1 Part One Manifestos and Theoretical Writings Introduction to Part One Lawrence Rainey 43 The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909) F. -

Copyright by Laura Kathleen Valeri 2011

Copyright by Laura Kathleen Valeri 2011 The Thesis Committee for Laura Kathleen Valeri Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rediscovering Maurice Maeterlinck and His Significance for Modern Art APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Linda D. Henderson Richard A. Shiff Rediscovering Maurice Maeterlinck and His Significance for Modern Art by Laura Kathleen Valeri, BA Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Abstract Rediscovering Maurice Maeterlinck and His Significance for Modern Art Laura Kathleen Valeri, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 Supervisor: Linda D. Henderson This thesis examines the impact of Maurice Maeterlinck’s ideas on modern artists. Maeterlinck's poetry, prose, and early plays explore inherently Symbolist issues, but a closer look at his works reveals a departure from the common conception of Symbolism. Most Symbolists adhered to correspondence theory, the idea that the external world within the reach of the senses consisted merely of symbols that reflected a higher, objective reality hidden from humans. Maeterlinck rarely mentioned symbols, instead claiming that quiet contemplation allowed him to gain intuitions of a subjective, truer reality. Maeterlinck’s use of ambiguity and suggestion to evoke personal intuitions appealed not only to nineteenth-century Symbolist artists like Édouard Vuillard, but also to artists in pre-World War I Paris, where a strong Symbolist current continued. Maeterlinck’s ideas also offered a parallel to the theories of Henri Bergson, embraced by the Puteaux Cubists Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes. -

Cœur, Temps and Monde in Le Forçat Innocent of Supervielle: a Poet’S Existential Metaphors of Prison and Shelter

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 33 Issue 1 Article 8 1-1-2009 Cœur, Temps and Monde in Le forçat innocent of Supervielle: A Poet’s Existential Metaphors of Prison and Shelter Franck Dalmas Stony Brook University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Dalmas, Franck (2009) "Cœur, Temps and Monde in Le forçat innocent of Supervielle: A Poet’s Existential Metaphors of Prison and Shelter," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 33: Iss. 1, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1695 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cœur, Temps and Monde in Le forçat innocent of Supervielle: A Poet’s Existential Metaphors of Prison and Shelter Abstract Poet Jules Supervielle has a marginal status in twentieth-century French literature as he was not engaged in any prominent movement of his time (Symbolism, Futurism, or Surrealism). In that regard, his poetry is neither nationally colored nor aesthetically connoted. It might well be the reason for his lacking consideration in the literary canon. But these differences must get our special attention. Supervielle was not born in France and he was to live and write his works in a state of existential angst, divided, as he always felt, between his native Uruguay and his French legacy. -

Motivation of the Sign 261 Discussion 287

Picasso and Braque A SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZED BY William Rubin \ MODERATED BY Kirk Varnedoe PROCEEDINGS EDITED BY Lynn Zelevansky THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK Contents Richard E. Oldenburg Foreword 7 William Rubin and Preface and Acknowledgments 9 Lynn Zelevansky Theodore Reff The Reaction Against Fauvism: The Case of Braque 17 Discussion 44 David Cottington Cubism, Aestheticism, Modernism 58 Discussion 73 Edward F. Fry Convergence of Traditions: The Cubism of Picasso and Braque 92 Discussion i07 Christine Poggi Braque’s Early Papiers Colles: The Certainties o/Faux Bois 129 Discussion 150 Yve-Alain Bois The Semiology of Cubism 169 Discussion 209 Mark Roskill Braque’s Papiers Colles and the Feminine Side to Cubism 222 Discussion 240 Rosalind Krauss The Motivation of the Sign 261 Discussion 287 Pierre Daix Appe ndix 1 306 The Chronology of Proto-Cubism: New Data on the Opening of the Picasso/Braque Dialogue Pepe Karmel Appe ndix 2 322 Notes on the Dating of Works Participants in the Symposium 351 The Motivation of the Sign ROSALIND RRAUSS Perhaps we should start at the center of the argument, with a reading of a papier colle by Picasso. This object, from the group dated late November-December 1912, comes from that phase of Picasso’s exploration in which the collage vocabulary has been reduced to a minimalist austerity. For in this run Picasso restricts his palette of pasted mate rial almost exclusively to newsprint. Indeed, in the papier colle in question, Violin (fig. 1), two newsprint fragments, one of them bearing h dispatch from the Balkans datelined TCHATALDJA, are imported into the graphic atmosphere of charcoal and drawing paper as the sole elements added to its surface.