Time Regained Proust, Marcel (Translator: Stephen Hudson)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land of Horses 2020

LAND OF HORSES 2020 « Far back, far back in our dark soul the horse prances… The horse, the horse! The symbol of surging potency and power of movement, of action in man! D.H. Lawrence EDITORIAL With its rich equine heritage, Normandy is the very definition of an area of equine excellence. From the Norman cavalry that enabled William the Conqueror to accede to the throne of England to the current champions who are winning equestrian sports events and races throughout the world, this historical and living heritage is closely connected to the distinctive features of Normandy, to its history, its culture and to its specific way of life. Whether you are attending emblematic events, visiting historical sites or heading through the gates of a stud farm, discovering the world of Horses in « Normandy is an opportunity to explore an authentic, dynamic and passionate region! Laurence MEUNIER Normandy Horse Council President SOMMAIRE > HORSE IN NORMANDY P. 5-13 • normandy the world’s stables • légendary horses • horse vocabulary INSPIRATIONS P. 14-21 • the fantastic five • athletes in action • les chevaux font le show IIDEAS FOR STAYS P. 22-29 • 24h in deauville • in the heart of the stud farm • from the meadow to the tracks, 100% racing • hooves and manes in le perche • seashells and equines DESTINATIONS P. 30-55 • deauville • cabourg and pays d’auge • le pin stud farm • le perche • saint-lô and cotentin • mont-saint-michel’s bay • rouen SADDLE UP ! < P. 56-60 CABOURG AND LE PIN PAYS D’AUGE STUD P. 36-39 FARM DEAUVILLE P. -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany Including Recent Acquisitions. Catalogue 286 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.reeseco.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. Institutional billing requirements may, as always, be accommodated upon request. -

Retriever (Labrador)

Health - DNA Test Report: DNA - HNPK Gundog - Retriever (Labrador) Dog Name Reg No DOB Sex Sire Dam Test Date Test Result A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S EL TORO AT AV0901389 27/08/2017 Dog BLACKSUGAR LUIS WATERLINE'S SELLERIA 27/11/2018 Clear BALLADOOLE (IMP DEU) (ATCAQ02385BEL) A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S GET LUCKY (IMP AV0904592 09/04/2018 Dog CLEARCREEK BONAVENTURE A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S TEA FOR 27/11/2018 Clear DEU) WINDSOCK TWO (IMP DEU) AALINCARREY PUMPKIN AT LADROW AT04277704 30/10/2016 Bitch MATTAND EXODUS AALINCARREY SUMMER LOVE 20/11/2018 Carrier AALINCARREY SUMMER LOVE AR03425707 19/08/2014 Bitch BRIGHTON SARRACENIA (IMP POL) AALINCARREY FAIRY DUST 27/08/2019 Carrier AALINCARREY SUMMER MAGIC AR03425706 19/08/2014 Dog BRIGHTON SARRACENIA (IMP POL) AALINCARREY FAIRY DUST 23/08/2017 Clear AALINCARREY WISPA AT01657504 09/04/2016 Bitch AALINCARREY MANNANAN AFINMORE AIRS AND GRACES 03/03/2020 Clear AARDVAR WINCHESTER AH02202701 09/05/2007 Dog AMBERSTOPE BLUE MOON TISSALIAN GIGI 12/09/2016 Clear AARDVAR WOODWARD AR03033605 25/08/2014 Dog AMBERSTOPE REBEL YELL CAMBREMER SEE THE STARS 29/11/2016 Carrier AARDVAR ZOLI AU00841405 31/01/2017 Bitch AARDVAR WINCHESTER CAMBREMER SEE THE STARS 12/04/2017 Clear ABBEYSTEAD GLAMOUR AT TANRONENS AW03454808 20/08/2019 Bitch GLOBETROTTER LAB'S VALLEY AT ABBEYSTEAD HOPE 25/02/2021 Clear BRIGBURN (IMP SVK) ABBEYSTEAD HORATIO OF HASELORHILL AU01380005 07/03/2017 Dog ROCHEBY HORN BLOWER HASELORHILL ENCORE 05/12/2019 Clear ABBEYSTEAD PAGEANT AT RUMHILL AV01630402 10/04/2018 Dog PARADOCS BELLWETHER HEATH HASELORHILL ENCORE -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 73-20,631

THE EFFORT TO ESCAPE FROM TEMPORAL CONSCIOUSNESS AS EXPRESSED IN THE THOUGHT AND WORK OF HERMAN HESSE, HANNAH ARENDT, AND KARL LOEWITH Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Olsen, Gary Raymond, 1940- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 18:13:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288040 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Paga(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. -

CSI5*-WA Coruña

CSI5*-W A Coruña 13th - 15th(ESP) December 2019 Casas Novas Equestrian Centre 02 TROFEO ESTRELLA GALICIA CSI2* - Int. jumping competition in two phases Table A, FEI Art. 274.1.5.3 Height: 1.40 m Begin: Friday, 13.12.2019 - 15.15 hrs O F F I C I A L R E S U L T Rk CNR Horse Rider Nation Result 1. 101 Llain de Llamosas Jesus Garmendia Echevarria ESP 0 penalties 24.05 sec bay / 8y / G / 105PI37 / Colomer Barrera,Francisco 2.310,00 EUR phase 2 2. 124 Coltaire Jacobo Fontan Garcia ESP 0 penalties 24.29 sec bay / 9y / G / ISH / 105LL19 / Sergio Valdemar Freitas F. Sousa / Marion Hughes 1.400,00 EUR phase 2 3. 129 Balasco de l'Abbaye Pedro Fernando Mateos Rodriguez ESP 0 penalties 24.69 sec chest / 8y / G / Ugano Sitte / Le Tot de Semilly / SF / 105IU66 / Miguel Angel GIL / Louis Leconte 1.050,00 EUR phase 2 4. 103 AD Amigo B Gonzalo Añon Suarez ESP 0 penalties 24.77 sec bay / 14y / S / Tadmus / Heartbreaker / KWPN / 103AX27 / Añon Team Horses S.L. / MTS.G. En G.F. Brinkman,Zutphen (ne 700,00 EUR phase 2 5. 176 Dento Bernardo Ladeira POR 0 penalties 25.05 sec grey / 11y / S / Cardento / Iroko / KWPN / 103QM30 / Bl Horses,Lda / A.F. Oude Nijeweme,Haarle (ned) 420,00 EUR phase 2 6. 170 Tornado v. Teresa Blazquez - Abascal ESP 0 penalties 25.18 sec bay / 8y / G / Toulon / Contender / HOLST / 105JJ47 / Yeguada Valbanera S.L. / Schockemöhle,Vanessa 315,00 EUR phase 2 7. -

Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: DOI: 10.7766/Orbit.V1.1.30

Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon https://www.pynchon.net ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): Erik Ketzan Affiliation(s): Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Mannheim, Germany Title: Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/30 DOI: 10.7766/orbit.v1.1.30 Abstract: This paper argues that Pynchon may allude to Marcel Proust through the character Marcel in Part 4 of Gravity's Rainbow and, if so, what that could mean. I trace the textual clues that relate to Proust and analyze what Pynchon may be saying about a fellow great experimental writer. Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Erik Ketzan Editorial note: a previous draft of this paper appeared on The Modern Word in 2010. Remember the "Floundering Four" part in Gravity's Rainbow? It's a short story of sorts that takes place in a city of the future called Raketen-Stadt (German for "Rocket City") and features a cast of comic book-style super heroes called the Floundering Four. One of them is named Marcel, and I submit that he is meant as some kind of representation of the great Marcel Proust. Only eight pages long, the Floundering Four section is a parody/riff on a sci-fi comic book story, loosely patterned on The Fantastic Four by Marvel Comics. It appears near the end of Gravity's Rainbow among a set of thirteen chapterettes, each one a fragmentary "text". As Pynchon scholar Steven Weisenburger explains, "A variety of discourses, modes and forms are parodied in the… subsections.. -

Jonathan Greenberg

Losing Track of Time Jonathan Greenberg Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation tells a story of doing nothing; it is an antinovel whose heroine attempts to sleep for a year in order to lose track of time. This desire to lose track of time constitutes a refusal of plot, a satiric and passive- aggressive rejection of the kinds of narrative sequences that novels typically employ but that, Moshfegh implies, offer nothing but accommodation to an unhealthy late capitalist society. Yet the effort to stifle plot is revealed, paradoxically, as an ambi- tion to be achieved through plot, and so in resisting what novels do, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends up showing us what novels do. Being an antinovel turns out to be just another way of being a novel; in seeking to lose track of time, the novel at- tunes us to our being in time. Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed.1 For a long time I used to go to bed early.2 he first of these sentences begins Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2018 novelMy Year of Rest and Relaxation; the second, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. More ac- T curately, the second sentence begins C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Proust, whose French reads, “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” D. J. Enright emends the translation to “I would go to bed”; Lydia Davis and Google Translate opt for “I went to bed.” What the translators famously wrestle with is how to render Proust’s ungrammatical combination of the completed action of the passé composé (“went to bed”) with a modifier (“long time”) that implies a re- peated, habitual, or everyday action. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

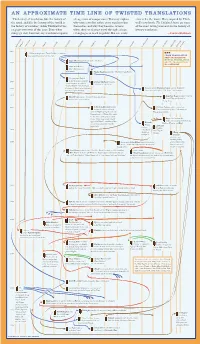

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE of TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The History of Translation, Like the History of a Long Series of Compromises

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE OF TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The history of translation, like the history of a long series of compromises. This may explain error is for the worse. Here, inspired by Thirl- the novel, and like the history of the world, is why some novelists refuse every translator but well’s new book, The Delighted States, are some the history of mistakes,” Adam Thirlwell writes themselves, and why they become anxious of the most vexing moments in the history of on page seventeen of this issue. Even when when their work must travel through a chain literary translation. things go well, however, any translation requires of languages to reach its public. But not every —Jascha Hoffman E N S E A N H I H H N N U N H H A C A S H S I C S A A H G A S I S N L I H H I I C I I I I B B L M S U D A A T C C N N S I T S N D U B A T G E R L S E R T L E N R R A D L R A E Z U N I R E E O O U P W I O A A C C C D E F F G P P P R S S Y Y 1490 KEY: A Valencian knight writes Tirant Lo Blanc in Catalan. CHAIN TRANSLATION It is finished by a friend after his death. SELF TRANSLATION Edgar Allan Poe publishes his poem “The Raven.” MUTUAL TRANSLATION 1850 GROUP TRANSLATION NO CATEGORY Lewis Carroll writes Alice’s Adventures in W onderland. -

1 NUMBER 96 FALL 2019-FALL 2020 in Memoriam

Virginia Woolf Miscellany NUMBER 96 FALL 2019-FALL 2020 Centennial Contemplations on Early Work (16) while Rosie Reynolds examines the numerous by Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf o o o o references to aunts in The Voyage Out and examines You can access issues of the the narrative function of Rachel’s aunt, Helen To observe the centennial of Virginia Woolf’s Virginia Woolf Miscellany Ambrose, exploring Helen’s perspective as well as early works, The Voyage Out, and Night and online on WordPress at the identity and self-revelation associated with the Day, and also Leonard Woolf’s The Village in the https://virginiawoolfmiscellany. emerging relationship between Rachel and fellow Jungle. I invited readers to adopt Nobel Laureate wordpress.com/ tourist Terence. Daniel Kahneman’s approach to problem-solving and decision making. In Thinking Fast and Slow, Virginia Woolf Miscellany: In her essay, Mine Özyurt Kılıç responds directly Kahneman distinguishes between fast thinking— Editorial Board and the Editors to the call with a “slow” reading of the production typically intuitive, impressionistic and reliant on See page 2 process that characterizes the work of Hogarth Press, associative memory—and the more deliberate, Editorial Policies particularly in contrast to the mechanized systems precise, detailed, and logical process he calls slow See page 6 from which it was distinguished. She draws upon “A thinking. Fast thinking is intuitive, impressionistic, y Mark on the Wall,” “Kew Gardens,” and “Modern and dependent upon associative memory. Slow – TABLE OF CONTENTS – Fiction,” to develop the notion and explore the thinking is deliberate, precise, detailed, and logical. -

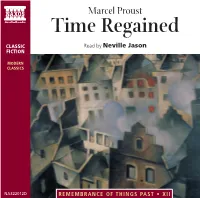

Marcel Proust Time Regained

Marcel Proust Time Regained CLASSIC Read by Neville Jason FICTION MODERN CLASSICS NA322012D REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST • XII 1 At Tansonville with Gilberte 7:37 2 Saint-Loup insisted I should remain… 6:15 3 Years in a sanatorium with a visit to Paris in 1914 4:32 4 At dinner time the restaurants were full… 2:55 5 Occasional meetings with Baron de Charlus 6:19 6 A return to the sanatorium 3:37 7 On my second return to Paris – another letter 3:55 8 A visit from Robert de Saint-Loup 3:18 9 Thinking about Saint-Loup’s visit 7:01 10 A further vendetta against Baron de Charlus 7:49 11 The views of Baron de Charlus 5:24 12 The destruction of men and the effect of the War 6:36 13 The aeroplanes passing through the night sky 7:46 14 Among abandoned, derelict houses,… 4:14 15 Entrance to the house followed by a sailor 2:01 16 A shocking discovery 6:22 17 ‘I implore you, mercy, mercy, have pity’ 2:49 18 A croix-de-guerre had been found on the floor 10:27 19 News of the death of Robert de Saint 10:56 20 Back to another sanatorium 2:44 21 I ordered a carriage to take me to the party 6:43 22 I got down from the carriage again 2:00 2 23 I stumble on some uneven paving stones 4:13 24 I entered the Guermantes’s mansion 3:55 25 I forced myself to try and see clearly 8:52 26 Fragments of existence removed from time 3:27 27 As I entered the Prince de Guermantes’s library 4:02 28 Real life… which has been uncovered… 5:59 29 At this moment, the butler arrived… 6:56 30 The Duchesse de Guermantes: 4:23 31 Old age, the meaning of death 8:03 32 Odette – looking -

Notes on Contributors 7 6 7

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS 7 6 7 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS ALLEN, Walter. Novelist and Literary Critic. Author of six novels (the most recent being All in a Lifetime, 1959); several critical works, including Arnold Bennett, 1948; Reading a Novel, 1949 (revised, 1956); Joyce Cary, 1953 (revised, 1971); The English Novel, 1954; Six Great Novelists, 1955; The Novel Today, 1955 (revised, 1966); George Eliot, 1964; and The Modern Novel in Britain and the United States, 1964; and of travel books, social history, and books for children. Editor of Writers on Writing, 1948, and of The Roaring Queen by Wyndham Lewis, 1973. Has taught at several universities in Britain, the United States, and Canada, and been an editor of the New Statesman. Essays: Richard Hughes; Ring Lardner; Dorothy Richardson; H. G. Wells. ANDERSON, David D. Professor of American Thought and Language, Michigan State University, East Lansing; Editor of University College Quarterly and Midamerica. Author of Louis Bromfield, 1964; Critical Studies in American Literature, 1964; Sherwood Anderson, 1967; Anderson's "Winesburg, Ohio," 1967; Brand Whitlock, 1968; Abraham Lincoln, 1970; Robert Ingersoll, 1972; Woodrow Wilson, 1975. Editor or Co-Editor of The Black Experience, 1969; The Literary Works of Lincoln, 1970; The Dark and Tangled Path, 1971 ; Sunshine and Smoke, 1971. Essay: Louis Bromfield. ANGLE, James. Assistant Professor of English, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti. Author of verse and fiction in periodicals, and of an article on Edward Lewis Wallant in Kansas Quarterly, Fall 1975. Essay: Edward Lewis Wallant. ASHLEY, Leonard R.N. Professor of English, Brooklyn College, City University of New York. Author of Colley Cibber, 1965; 19th-Century British Drama, 1967; Authorship and Evidence: A Study of Attribution and the Renaissance Drama, 1968; History of the Short Story, 1968; George Peele: The Man and His Work, 1970.