A Year United in Fragmentation: an Examination Into the History Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cutting Patterns in DW Griffith's Biographs

Cutting patterns in D.W. Griffith’s Biographs: An experimental statistical study Mike Baxter, 16 Lady Bay Road, West Bridgford, Nottingham, NG2 5BJ, U.K. (e-mail: [email protected]) 1 Introduction A number of recent studies have examined statistical methods for investigating cutting patterns within films, for the purposes of comparing patterns across films and/or for summarising ‘average’ patterns in a body of films. The present paper investigates how different ideas that have been proposed might be combined to identify subsets of similarly constructed films (i.e. exhibiting comparable cutting structures) within a larger body. The ideas explored are illustrated using a sample of 62 D.W Griffith Biograph one-reelers from the years 1909–1913. Yuri Tsivian has suggested that ‘all films are different as far as their SL struc- tures; yet some are less different than others’. Barry Salt, with specific reference to the question of whether or not Griffith’s Biographs ‘have the same large scale variations in their shot lengths along the length of the film’ says the ‘answer to this is quite clearly, no’. This judgment is based on smooths of the data using seventh degree trendlines and the observation that these ‘are nearly all quite different one from another, and too varied to allow any grouping that could be matched against, say, genre’1. While the basis for Salt’s view is clear Tsivian’s apparently oppos- ing position that some films are ‘less different than others’ seems to me to be a reasonably incontestable sentiment. It depends on how much you are prepared to simplify structure by smoothing in order to effect comparisons. -

Paranoid Modernism in Joyce and Kafka

Article Paranoid Modernism in Joyce and Kafka SPURR, David Anton Abstract This essay considers the work of Joyce and Kafka in terms of paranoia as interpretive delirium, the imagined but internally coherent interpretation of the world whose relation to the real remains undecidable. Classic elements of paranoia are manifest in both writers insofar as their work stages scenes in which the figure of the artist or a subjective equivalent perceives himself as the object of hostility and persecution. Nonetheless, such scenes and the modes in which they are rendered can also be understood as the means by which literary modernism resisted forces hostile to art but inherent in the social and economic conditions of modernity. From this perspective the work of both Joyce and Kafka intersects with that of surrealists like Dali for whom the positive sense of paranoia as artistic practice answered the need for a systematic objectification of the oniric underside of reason, “the world of delirium unknown to rational experience.” Reference SPURR, David Anton. Paranoid Modernism in Joyce and Kafka. Journal of Modern Literature , 2011, vol. 34, no. 2, p. 178-191 DOI : 10.2979/jmodelite.34.2.178 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:16597 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Paranoid Modernism in Joyce and Kafka David Spurr Université de Genève This essay considers the work of Joyce and Kafka in terms of paranoia as interpretive delirium, the imagined but internally coherent interpretation of the world whose rela- tion to the real remains undecidable. Classic elements of paranoia are manifest in both writers insofar as their work stages scenes in which the figure of the artist or a subjective equivalent perceives himself as the object of hostility and persecution. -

Joyce's Jewish Stew: the Alimentary Lists in Ulysses

Colby Quarterly Volume 31 Issue 3 September Article 5 September 1995 Joyce's Jewish Stew: The Alimentary Lists in Ulysses Jaye Berman Montresor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 31, no.3, September 1995, p.194-203 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Montresor: Joyce's Jewish Stew: The Alimentary Lists in Ulysses Joyce's Jewish Stew: The Alimentary Lists in Ulysses by JAYE BERMAN MONTRESOR N THEIR PUN-FILLED ARTICLE, "Towards an Interpretation ofUlysses: Metonymy I and Gastronomy: A Bloom with a Stew," an equally whimsical pair ofcritics (who prefer to remain pseudonymous) assert that "the key to the work lies in gastronomy," that "Joyce's overriding concern was to abolish the dietary laws ofthe tribes ofIsrael," and conclude that "the book is in fact a stew! ... Ulysses is a recipe for bouillabaisse" (Longa and Brevis 5-6). Like "Longa" and "Brevis'"interpretation, James Joyce's tone is often satiric, and this is especially to be seen in his handling ofLeopold Bloom's ambivalent orality as a defining aspect of his Jewishness. While orality is an anti-Semitic assumption, the source ofBloom's oral nature is to be found in his Irish Catholic creator. This can be seen, for example, in Joyce's letter to his brother Stanislaus, penned shortly after running off with Nora Barnacle in 1904, where we see in Joyce's attention to mealtimes the need to present his illicit sexual relationship in terms of domestic routine: We get out ofbed at nine and Nora makes chocolate. -

Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: DOI: 10.7766/Orbit.V1.1.30

Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon https://www.pynchon.net ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): Erik Ketzan Affiliation(s): Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Mannheim, Germany Title: Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/30 DOI: 10.7766/orbit.v1.1.30 Abstract: This paper argues that Pynchon may allude to Marcel Proust through the character Marcel in Part 4 of Gravity's Rainbow and, if so, what that could mean. I trace the textual clues that relate to Proust and analyze what Pynchon may be saying about a fellow great experimental writer. Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Erik Ketzan Editorial note: a previous draft of this paper appeared on The Modern Word in 2010. Remember the "Floundering Four" part in Gravity's Rainbow? It's a short story of sorts that takes place in a city of the future called Raketen-Stadt (German for "Rocket City") and features a cast of comic book-style super heroes called the Floundering Four. One of them is named Marcel, and I submit that he is meant as some kind of representation of the great Marcel Proust. Only eight pages long, the Floundering Four section is a parody/riff on a sci-fi comic book story, loosely patterned on The Fantastic Four by Marvel Comics. It appears near the end of Gravity's Rainbow among a set of thirteen chapterettes, each one a fragmentary "text". As Pynchon scholar Steven Weisenburger explains, "A variety of discourses, modes and forms are parodied in the… subsections.. -

Jonathan Greenberg

Losing Track of Time Jonathan Greenberg Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation tells a story of doing nothing; it is an antinovel whose heroine attempts to sleep for a year in order to lose track of time. This desire to lose track of time constitutes a refusal of plot, a satiric and passive- aggressive rejection of the kinds of narrative sequences that novels typically employ but that, Moshfegh implies, offer nothing but accommodation to an unhealthy late capitalist society. Yet the effort to stifle plot is revealed, paradoxically, as an ambi- tion to be achieved through plot, and so in resisting what novels do, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends up showing us what novels do. Being an antinovel turns out to be just another way of being a novel; in seeking to lose track of time, the novel at- tunes us to our being in time. Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed.1 For a long time I used to go to bed early.2 he first of these sentences begins Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2018 novelMy Year of Rest and Relaxation; the second, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. More ac- T curately, the second sentence begins C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Proust, whose French reads, “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” D. J. Enright emends the translation to “I would go to bed”; Lydia Davis and Google Translate opt for “I went to bed.” What the translators famously wrestle with is how to render Proust’s ungrammatical combination of the completed action of the passé composé (“went to bed”) with a modifier (“long time”) that implies a re- peated, habitual, or everyday action. -

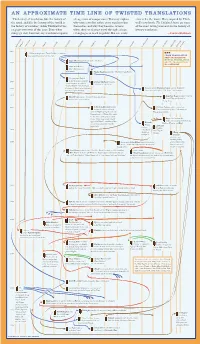

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE of TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The History of Translation, Like the History of a Long Series of Compromises

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE OF TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The history of translation, like the history of a long series of compromises. This may explain error is for the worse. Here, inspired by Thirl- the novel, and like the history of the world, is why some novelists refuse every translator but well’s new book, The Delighted States, are some the history of mistakes,” Adam Thirlwell writes themselves, and why they become anxious of the most vexing moments in the history of on page seventeen of this issue. Even when when their work must travel through a chain literary translation. things go well, however, any translation requires of languages to reach its public. But not every —Jascha Hoffman E N S E A N H I H H N N U N H H A C A S H S I C S A A H G A S I S N L I H H I I C I I I I B B L M S U D A A T C C N N S I T S N D U B A T G E R L S E R T L E N R R A D L R A E Z U N I R E E O O U P W I O A A C C C D E F F G P P P R S S Y Y 1490 KEY: A Valencian knight writes Tirant Lo Blanc in Catalan. CHAIN TRANSLATION It is finished by a friend after his death. SELF TRANSLATION Edgar Allan Poe publishes his poem “The Raven.” MUTUAL TRANSLATION 1850 GROUP TRANSLATION NO CATEGORY Lewis Carroll writes Alice’s Adventures in W onderland. -

Film and Politics

Politics and Film PS 350 – Spring 2015 Instructor: Jay Steinmetz – [email protected] Office hours and location: Wednesdays – 3 to 5, PLC 808 GTFs: TBD Culture constitutes shared signs and expressions that can reveal, determine, and otherwise influence politics. The film medium is perfectly tailored for this: the power of moving image with sound, reflected in public spaces, produces politically charged identities and influences the way spectators see themselves and their shared communities. Moreover, the interwoven nature of the economic and social in cinema makes it an especially intriguing site for observing change of political culture over time. The economic commodity of the cinema is necessarily social—a nexus of public and shared images of the world. Conversely, the social constraints (ie moral regulation or censorship of film content) is necessarily shaped by economic factors. The “Dream Machine” of Hollywood is a potent meaning-making site not just for Americans but across the world (today, roughly half of a Hollywood film’s revenue often comes from overseas), and so this course will pay close attention to Hollywood film texts and contexts in a global setting. The second half of the term (starting in Week 5) will shift to a comparative approach, contrasting American and Italian film styles, industries, regulatory concerns, and economic strategies. Analytic comparison is a crucial aspect of this course—be it comparisons across genres, time periods, films, or industries—and will culminate in a comparative research paper due on Week 10. There will be one film screening in class every week. Please note: Attendance to these screenings is part of your class responsibilities. -

Ulysses: the Novel, the Author and the Translators

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 21-27, January 2011 © 2011 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.1.1.21-27 Ulysses: The Novel, the Author and the Translators Qing Wang Shandong Jiaotong University, Jinan, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—A novel of kaleidoscopic styles, Ulysses best displays James Joyce’s creativity as a renowned modernist novelist. Joyce maneuvers freely the English language to express a deep hatred for religious hypocrisy and colonizing oppressions as well as a well-masked patriotism for his motherland. In this aspect Joyce shares some similarity with his Chinese translator Xiao Qian, also a prolific writer. Index Terms—style, translation, Ulysses, James Joyce, Xiao Qian I. INTRODUCTION James Joyce (1882-1941) is regarded as one of the most innovative novelists of the 20th century. For people who are interested in modernist novels, Ulysses is an enormous aesthetic achievement. Attridge (1990, p.1) asserts that the impact of Joyce‟s literary revolution was such that “far more people read Joyce than are aware of it”, and that few later novelists “have escaped its aftershock, even when they attempt to avoid Joycean paradigms and procedures.” Gillespie and Gillespie (2000, p.1) also agree that Ulysses is “a work of art rivaled by few authors in this or any century.” Ezra Pound was one of the first to recognize the gift in Joyce. He was convinced of the greatness of Ulysses no sooner than having just read the manuscript for the first part of the novel in 1917. -

National Film Registry

National Film Registry Title Year EIDR ID Newark Athlete 1891 10.5240/FEE2-E691-79FD-3A8F-1535-F Blacksmith Scene 1893 10.5240/2AB8-4AFC-2553-80C1-9064-6 Dickson Experimental Sound Film 1894 10.5240/4EB8-26E6-47B7-0C2C-7D53-D Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze 1894 10.5240/B1CF-7D4D-6EE3-9883-F9A7-E Rip Van Winkle 1896 10.5240/0DA5-5701-4379-AC3B-1CC2-D The Kiss 1896 10.5240/BA2A-9E43-B6B1-A6AC-4974-8 Corbett-Fitzsimmons Title Fight 1897 10.5240/CE60-6F70-BD9E-5000-20AF-U Demolishing and Building Up the Star Theatre 1901 10.5240/65B2-B45C-F31B-8BB6-7AF3-S President McKinley Inauguration Footage 1901 10.5240/C276-6C50-F95E-F5D5-8DCB-L The Great Train Robbery 1903 10.5240/7791-8534-2C23-9030-8610-5 Westinghouse Works 1904 1904 10.5240/F72F-DF8B-F0E4-C293-54EF-U A Trip Down Market Street 1906 10.5240/A2E6-ED22-1293-D668-F4AB-I Dream of a Rarebit Fiend 1906 10.5240/4D64-D9DD-7AA2-5554-1413-S San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906 1906 10.5240/69AE-11AD-4663-C176-E22B-I A Corner in Wheat 1909 10.5240/5E95-74AC-CF2C-3B9C-30BC-7 Lady Helen’s Escapade 1909 10.5240/0807-6B6B-F7BA-1702-BAFC-J Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy 1909 10.5240/C704-BD6D-0E12-719D-E093-E Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest 1910 10.5240/A8C0-4272-5D72-5611-D55A-S White Fawn’s Devotion 1910 10.5240/0132-74F5-FC39-1213-6D0D-Z Little Nemo 1911 10.5240/5A62-BCF8-51D5-64DB-1A86-H A Cure for Pokeritis 1912 10.5240/7E6A-CB37-B67E-A743-7341-L From the Manger to the Cross 1912 10.5240/5EBB-EE8A-91C0-8E48-DDA8-Q The Cry of the Children 1912 10.5240/C173-A4A7-2A2B-E702-33E8-N -

CLAUDIA BAEZ Paintings After Proust

ART 3 109 Ingraham Street T 646 331 3162 Brooklyn NY 11237 www.art-3gallery.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST Curated by Anne Strauss October 8 – November 22, 2014 Opening: Wednesday, October 8, 6 - 9 PM Claudia Baez, PAINTINGS after PROUST “And as she played, of all Albertine’s multiple tresses I could see but a single heart-shaped loop of black hair dinging to the side of her ear like the bow of a Velasquez Infanta.”, 2014, oil on canvas, 18 x 24 in. (45.7 x 61 cm.) © Claudia Baez Courtesy of ART 3 gallery Brooklyn, NY, September 19, 2014 – ART 3 opened in Bushwick in May 2014 near Luhring Augustine with its Inaugural Exhibition covered by The New York Times T Magazine, Primer. ART 3 was created by Silas Shabelewska-von Morisse, formerly of Haunch of Venison and Helly Nahmad Gallery. In July 2014, Monika Fabijanska, former Director of the Polish Cultural Institute in New York, joined ART 3 as Co-Director in charge of curatorial program, museums and institutions. ART 3 presents CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST on view at ART 3 gallery, 109 Ingraham Street, Bushwick, Brooklyn, from October 8 to November 22, 2014, Tue-Sat 12-6 PM. The opening will take place on Wednesday, October 8, from 6-9 PM. “In PAINTINGS after PROUST, Baez offers us an innovative chapter in contemporary painting in ciphering her art via a modernist work of literature within a postmodernist framework. […] In Claudia Baez’s exhibition literary narrative is poetically refracted through painting and vice versa, which the painter reminds us with artistic verve and aplomb of the adage that every picture tells a story as well as the other way around”. -

Cinefiles Document #5962

Document Citation Title D.W. Griffith touring show Author(s) Tom Gunning Ron Mottram Source Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1975 Type program note Language English Pagination No. of Pages 40 Subjects Griffith, D. W. (1875-1948), LaGrange, Kentucky, United States Film Subjects The fugitive, Griffith, D. W., 1910 The white rose, Griffith, D. W., 1923 Intolerance, Griffith, D. W., 1916 Broken blossoms, Griffith, D. W., 1919 Orphans of the storm, Griffith, D. W., 1921 America, Griffith, D. W., 1924 A corner in wheat, Griffith, D. W., 1909 Hearts of the world, Griffith, D. W., 1918 The avenging conscience, Griffith, D. W., 1914 Isn't life wonderful, Griffith, D. W., 1924 WARNING: This material may be protected by copyright law (Title 17 U.S. Code) The birth of a nation, Griffith, D. W., 1915 The girl and her trust, Griffith, D. W., 1912 The girl who stayed at home, Griffith, D. W., 1919 Way down east, Griffith, D. W., 1920 What shall we do with our old?, Griffith, D. W., 1911 Those awful hats, Griffith, D. W., 1909 Enoch Arden, Griffith, D. W., 1911 The honor of his family, Griffith, D. W., 1910 The painted lady, Griffith, D. W., 1912 The lady and the mouse, Griffith, D. W., 1912 The musketeers of Pig Alley, Griffith, D. W., 1912 The unchanging sea, Griffith, D. W., 1910 True heart Susie, Griffith, D. W., 1919 The battle at Elderbush Gulch, Griffith, D. W., 1914 An unseen enemy, Griffith, D. W., 1912 The struggle, Griffith, D. W., 1931 The mothering heart, Griffith, D. -

National Film Registry Titles Listed by Release Date

National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year Title Released Inducted Newark Athlete 1891 2010 Blacksmith Scene 1893 1995 Dickson Experimental Sound Film 1894-1895 2003 Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze 1894 2015 The Kiss 1896 1999 Rip Van Winkle 1896 1995 Corbett-Fitzsimmons Title Fight 1897 2012 Demolishing and Building Up the Star Theatre 1901 2002 President McKinley Inauguration Footage 1901 2000 The Great Train Robbery 1903 1990 Life of an American Fireman 1903 2016 Westinghouse Works 1904 1904 1998 Interior New York Subway, 14th Street to 42nd Street 1905 2017 Dream of a Rarebit Fiend 1906 2015 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906 1906 2005 A Trip Down Market Street 1906 2010 A Corner in Wheat 1909 1994 Lady Helen’s Escapade 1909 2004 Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy 1909 2003 Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest 1910 2005 White Fawn’s Devotion 1910 2008 Little Nemo 1911 2009 The Cry of the Children 1912 2011 A Cure for Pokeritis 1912 2011 From the Manger to the Cross 1912 1998 The Land Beyond the Sunset 1912 2000 Musketeers of Pig Alley 1912 2016 Bert Williams Lime Kiln Club Field Day 1913 2014 The Evidence of the Film 1913 2001 Matrimony’s Speed Limit 1913 2003 Preservation of the Sign Language 1913 2010 Traffic in Souls 1913 2006 The Bargain 1914 2010 The Exploits of Elaine 1914 1994 Gertie The Dinosaur 1914 1991 In the Land of the Head Hunters 1914 1999 Mabel’s Blunder 1914 2009 1 National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year