MONSIEUR PROUST: WHERE DID the TIME GO? a Collection Devoted to “À La Recherche Du Temps Perdu” by James Siranovich, Class of ’22 (Born ’74!)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: DOI: 10.7766/Orbit.V1.1.30

Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon https://www.pynchon.net ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): Erik Ketzan Affiliation(s): Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Mannheim, Germany Title: Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/30 DOI: 10.7766/orbit.v1.1.30 Abstract: This paper argues that Pynchon may allude to Marcel Proust through the character Marcel in Part 4 of Gravity's Rainbow and, if so, what that could mean. I trace the textual clues that relate to Proust and analyze what Pynchon may be saying about a fellow great experimental writer. Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Erik Ketzan Editorial note: a previous draft of this paper appeared on The Modern Word in 2010. Remember the "Floundering Four" part in Gravity's Rainbow? It's a short story of sorts that takes place in a city of the future called Raketen-Stadt (German for "Rocket City") and features a cast of comic book-style super heroes called the Floundering Four. One of them is named Marcel, and I submit that he is meant as some kind of representation of the great Marcel Proust. Only eight pages long, the Floundering Four section is a parody/riff on a sci-fi comic book story, loosely patterned on The Fantastic Four by Marvel Comics. It appears near the end of Gravity's Rainbow among a set of thirteen chapterettes, each one a fragmentary "text". As Pynchon scholar Steven Weisenburger explains, "A variety of discourses, modes and forms are parodied in the… subsections.. -

Jonathan Greenberg

Losing Track of Time Jonathan Greenberg Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation tells a story of doing nothing; it is an antinovel whose heroine attempts to sleep for a year in order to lose track of time. This desire to lose track of time constitutes a refusal of plot, a satiric and passive- aggressive rejection of the kinds of narrative sequences that novels typically employ but that, Moshfegh implies, offer nothing but accommodation to an unhealthy late capitalist society. Yet the effort to stifle plot is revealed, paradoxically, as an ambi- tion to be achieved through plot, and so in resisting what novels do, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends up showing us what novels do. Being an antinovel turns out to be just another way of being a novel; in seeking to lose track of time, the novel at- tunes us to our being in time. Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed.1 For a long time I used to go to bed early.2 he first of these sentences begins Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2018 novelMy Year of Rest and Relaxation; the second, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. More ac- T curately, the second sentence begins C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Proust, whose French reads, “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” D. J. Enright emends the translation to “I would go to bed”; Lydia Davis and Google Translate opt for “I went to bed.” What the translators famously wrestle with is how to render Proust’s ungrammatical combination of the completed action of the passé composé (“went to bed”) with a modifier (“long time”) that implies a re- peated, habitual, or everyday action. -

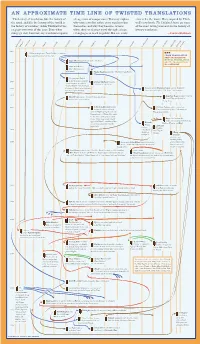

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE of TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The History of Translation, Like the History of a Long Series of Compromises

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE OF TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The history of translation, like the history of a long series of compromises. This may explain error is for the worse. Here, inspired by Thirl- the novel, and like the history of the world, is why some novelists refuse every translator but well’s new book, The Delighted States, are some the history of mistakes,” Adam Thirlwell writes themselves, and why they become anxious of the most vexing moments in the history of on page seventeen of this issue. Even when when their work must travel through a chain literary translation. things go well, however, any translation requires of languages to reach its public. But not every —Jascha Hoffman E N S E A N H I H H N N U N H H A C A S H S I C S A A H G A S I S N L I H H I I C I I I I B B L M S U D A A T C C N N S I T S N D U B A T G E R L S E R T L E N R R A D L R A E Z U N I R E E O O U P W I O A A C C C D E F F G P P P R S S Y Y 1490 KEY: A Valencian knight writes Tirant Lo Blanc in Catalan. CHAIN TRANSLATION It is finished by a friend after his death. SELF TRANSLATION Edgar Allan Poe publishes his poem “The Raven.” MUTUAL TRANSLATION 1850 GROUP TRANSLATION NO CATEGORY Lewis Carroll writes Alice’s Adventures in W onderland. -

CLAUDIA BAEZ Paintings After Proust

ART 3 109 Ingraham Street T 646 331 3162 Brooklyn NY 11237 www.art-3gallery.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST Curated by Anne Strauss October 8 – November 22, 2014 Opening: Wednesday, October 8, 6 - 9 PM Claudia Baez, PAINTINGS after PROUST “And as she played, of all Albertine’s multiple tresses I could see but a single heart-shaped loop of black hair dinging to the side of her ear like the bow of a Velasquez Infanta.”, 2014, oil on canvas, 18 x 24 in. (45.7 x 61 cm.) © Claudia Baez Courtesy of ART 3 gallery Brooklyn, NY, September 19, 2014 – ART 3 opened in Bushwick in May 2014 near Luhring Augustine with its Inaugural Exhibition covered by The New York Times T Magazine, Primer. ART 3 was created by Silas Shabelewska-von Morisse, formerly of Haunch of Venison and Helly Nahmad Gallery. In July 2014, Monika Fabijanska, former Director of the Polish Cultural Institute in New York, joined ART 3 as Co-Director in charge of curatorial program, museums and institutions. ART 3 presents CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST on view at ART 3 gallery, 109 Ingraham Street, Bushwick, Brooklyn, from October 8 to November 22, 2014, Tue-Sat 12-6 PM. The opening will take place on Wednesday, October 8, from 6-9 PM. “In PAINTINGS after PROUST, Baez offers us an innovative chapter in contemporary painting in ciphering her art via a modernist work of literature within a postmodernist framework. […] In Claudia Baez’s exhibition literary narrative is poetically refracted through painting and vice versa, which the painter reminds us with artistic verve and aplomb of the adage that every picture tells a story as well as the other way around”. -

Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust. John Stephen Larose Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Larose, John Stephen, "Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7206. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7206 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

An Obsession with Time in Selected Works of T

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 52 (2016) 207-215 EISSN 2392-2192 An Obsession with Time in Selected Works of T. S. Eliot as a Major Modernist Ensieh Shabanirad1,*, Ronak Ahmady Ahangar2 1Department of English Language and Literature, University of Tehran, Iran 2Department of English Language and Literature, University of Semnan, Iran *E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT As a poet, Eliot seems obsessed with time: the speaker of "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" keeps worrying about being late, and the passage of time in general as he gets older seems to continuously haunt him. In "The Waste Land" we have another form of obsession that presents itself in form of intertexuality; the many narrators of the poem go back and forth in time and provide almost random recollections of the past or haphazard bits of literary texts that are equally concerned with time. This article aims to look deeper into the importance of the concept time in Eliot's poetry, the two poems already mentioned as well as "Four Quartets" (in which a whole section is devoted to time and its philosophy) and then take the important works of other key figures of Modernism and the movement's characteristics into comparison in order to determine whether Eliot's seeming obsession is a fruit of its era or a personal motif of the poet. Keywords: T. S. Eliot; Concept of Time; Intertextuality; Modernist Poetry 1. INTRODUCTION T. S. Eliot is the well known leading figure of the Modernism movement and winner of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1948. -

New York University

New York University Spring 2020 CORE-UA 761 EXPRESSIVE CULTURES LA BELLE ÉPOQUE: PAINTING, MUSIC AND LITERATURE IN FRANCE 1852-1914 TUESDAY, THURSDAY 11-12.15 Cantor 101 Professor Thomas Ertman ([email protected]) This course takes as its subject the Belle Époque, that period in the life of France’s pre-World War I Third Republic (1871-1914) associated with extraordinary artistic achievement, as well as the Second Empire (1851-1871) that preceded it. Not only was Paris during this time the undisputed western capital of painting and sculpture, it also was the most important production site for new works of musical theater and, arguably, literature as well. It was during these decades that Impressionism launched its assault on the academic establishment, only to be superseded itself by an ever-changing avant-garde associated first with the Nabis, then with fauvism and cubism; that the operas of Bizet, Saint-Saëns and Massenet and the plays of Sardou and Rostand filled the world’s theaters; and that the novels of Zola and stories of Maupassant were translated into dozens of languages. Finally, this was the society that gave birth to one of the greatest literary works of all time, Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the first volume of which appeared just as World War I was about to bring the Belle Époque to a violent end. In this course, we will attempt to gain a deeper understanding of the artistic works of this era by placing them in the context of the society within which they were produced, France’s Second Empire and Third Republic. -

Milton Babbitt

A LIFE OF LEARNING Milton Babbitt Charles Homer Haskins Lecture American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 17 ISSN 1041-536X 1983 Maynard Mack Sterling Professor of English, Emeritus Yale University 1984 Mary Rosamond Haas Professor of Linguistics, Emeritus University of California, Berkeley 1985 Lawrence Stone Dodge Professor of History Princeton University 1986 Milton V Anastos Professor Emeritus of Byzantine Greek and History University of California, Los Angeles 1987 Carl E. Schorske Professor Emeritus of History Princeton University 1988 John Hope Franklin James B. Duke Professor Emeritus Duke University 1989 Judith N. Shklar John Cowles Professor of Government Harvard University 1990 Paul Oskar Kristeller Frederick J. E. Woodbridge Professor Emeritus of Philosophy Columbia University 1991 Milton Babbitt William Shubael Conant Professor Emeritus of Music Princeton University A LIFE OF LEARNING Milton Babbitt Charles Homer Haskins Lecture American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 17 CharlesHomer Haskins (1870-193 7), for whom the ACLS lecture series is named, was the first Chairman of the American Council of Learned Societies, 1920-26. He began his teaching career at the Johns Hopkins University, where he received the B.A. degree in 1887, and the Ph.D. in 1890. He later taught at the University of Wisconsin and at Harvard,where he was Henry CharlesLea Professor of Medieval History at the time of his retirement in 1931, and Dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences from 1908 to 1924. He served as president of the American Historical Association, 1922, and was a founder and the second president of the Medieval Academy of America, 1926. -

Discovering Neruda: an Interview with H

of that text's own intentions it may be the translator's imagination that is best able to relate it to the intentions of others. Notes 6Rainer Schulte, "The Act of Translation: From Interpretation to Interdisciplinary Thinking," Translation Review, NO.4 (1979), pp. 3-8. , Octavio Paz, "Traduccion: literatura y literalidad," in Traduccion: Schulte's suggestions for translation as re-vitalized critical reading Iiteratura y literalidad (Barcelona: Tusquets, 1971), pp. 7-21. An complement very well Roger Shattuck's recent call for a English translation of this essay ("Translation: Literature and reexamination of "the relations between criticism and its host, Literality") by Lynn Tuttle appeared in Translation Review, No.3 literature." See "How to Rescue Literature," The New York Review of (1979), pp. 13·19. Books, (17 April 1980), pp. 29-35. 2George Steiner, After Babel (New York: Oxford University Press, 70ctavio Armand, Piet menos mia, Special number of the magazine 1975) and Serge Gavronsky, "The Translator: From Piety to Escolios (Los Angeles: California State University, 1976), p. 9. Cannibalism," Sub-Stance, No. 16 (1977), pp. 53-62. BRamon del Valle-lnclan, La lampara maravillosa (Buenos Aires: 3Jorge Luis Borges, "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote," trans. Espasa-Calpe, 1948), pp. 129-30. James E. Irby in Labyrinths. Selected Stories and Other Writings, ed. 9Ernst Robert Curtius, European Uterature and the Latin Middle Ages, Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby (New York: New Directions, 1975), trans. Williard Trask (1953; rpt, New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1963), pp.36-44. pp. 345-346 and Carol Maier, "The Concept of Language in La 4Marilyn Gaddis Rose, "Entropy and Redundancy in Decadent Style: lampara maravillosa," in Waiting for Pegasus. -

Time Regained Proust, Marcel (Translator: Stephen Hudson)

Time Regained Proust, Marcel (Translator: Stephen Hudson) Published: 1931 Type(s): Novels, Romance Source: http://gutenberg.net.au 1 About Proust: Proust was born in Auteuil (the southern sector of Paris's then-rustic 16th arrondissement) at the home of his great-uncle, two months after the Treaty of Frankfurt formally ended the Franco-Prussian War. His birth took place during the violence that surrounded the suppression of the Paris Commune, and his childhood corresponds with the consolida- tion of the French Third Republic. Much of Remembrance of Things Past concerns the vast changes, most particularly the decline of the aristo- cracy and the rise of the middle classes, that occurred in France during the Third Republic and the fin de siècle. Proust's father, Achille Adrien Proust, was a famous doctor and epidemiologist, responsible for study- ing and attempting to remedy the causes and movements of cholera through Europe and Asia; he was the author of many articles and books on medicine and hygiene. Proust's mother, Jeanne Clémence Weil, was the daughter of a rich and cultured Jewish family. Her father was a banker. She was highly literate and well-read. Her letters demonstrate a well-developed sense of humour, and her command of English was suf- ficient for her to provide the necessary impetus to her son's later at- tempts to translate John Ruskin. By the age of nine, Proust had had his first serious asthma attack, and thereafter he was considered by himself, his family and his friends as a sickly child. Proust spent long holidays in the village of Illiers. -

Robyn Creswell Department of Comparative Literature S Yale University S 451 College St

Robyn Creswell Department of Comparative Literature s Yale University s 451 College St. New Haven, CT 06511 s T: (203) 432-4752 s [email protected] Professional Appointments 2014 — Yale University Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature 2011 — 2014 Brown University Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature 2010 — The Paris Review Poetry Editor Education 2012 New York University, Ph.D. in Comparative Literature Dissertation: Tradition and Translation: Poetic Modernism in Beirut Dissertation readers: Richard Sieburth, Philip Kennedy, Xudong Zhang 2005 New York University, M.A. in Comparative Literature Thesis: Claims of Kinship: al-Hariri’s Maqamat and Habibi’s al-Mutasha’il 1999 Brown University, B.A. in Comparative Literature Magna cum laude Peer-Reviewed Publications “Crise de vers: Adonis’ Diwan and the Institution of Modernism,” Modernism/Modernity 17:4 (November 2010), 877-898. “Modernism in Translation: Poetry and Intellectual History in Beirut,” in Transformations of Modern Arabic Thought: Middle East Intellectual History after the Liberal Age, eds. Max Weiss and Jens Hanssen, Princeton University Press [forthcominG, 2015] “The Poetry of Jihad” (with Bernard Haykel) in Jihadi Culture: The Art and Social Practices of Militant Islamists, ed. Thomas HeGGhammer, CambridGe University Press [forthcominG, 2016] Literary Journalism Essays “The First Great Arabic Novel,” The New York Review of Books, October 8, 2015. “Battle Lines,” The New Yorker, June 8 & 15, 2015. “Syria’s Lost Spring,” The New York Review of Books [blog], February 16, 2015. “Art Beyond Politics,” Harper’s Magazine [bloG], AuGust 26, 2014. “Escaping Beirut,” The New York Review of Books [blog], March 25, 2014. “Poetry in Extremis,” The New Yorker [blog], February 13, 2014. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time I: Swann’s Way,trans. C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin, rev. by D.J. Enright (London: Vintage, 2002), p. 43. 2. Ibid. 3. Ibid. 4. Ibid., p. 44. 5. For an account of sexual perversions in the pre-modern, pre- sexological era, see, for example, Julie Peakman, ‘Sexual Perver- sion in History: An Introduction’, in Julie Peakman (ed.), Sexual Perversions, 1670–1890 (New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), pp. 1–49, and other essays in that collection. 6. Michel Foucault, The Will to Knowledge: The History of Sexuality Volume 1, trans. Robert Hurley (London: Penguin, 1998). 7. Roger Griffin, Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), pp. 45–6. 8. Anthony Giddens, The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies (Cambridge: Polity, 1992). 9. Cf. Richard G. Olson, Science and Scientism in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Urbana, IL and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2008), p. 294. 10. Cf. ibid., pp. 294 and 301–2. 11. Cf. Griffin, Modernism and Fascism, p. 90. 12. Max Nordau, Degeneration, trans. George L. Mosse (Lincoln, NE and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), p. 536. 13. Ibid., p. v. 14. Cf. Vernon A. Rosario, The Erotic Imagination: French Histories of Perversity (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 88. 15. Ibid., p. 40. 16. Thomas W. Laqueur, Solitary Sex: A Cultural History of Masturba- tion (New York: Zone Books, 2003), p. 278. 17. Griffin, Modernism and Fascism, p.