Maravich 1 Ozymandias: a Complete Analysis I Met a Traveller from An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

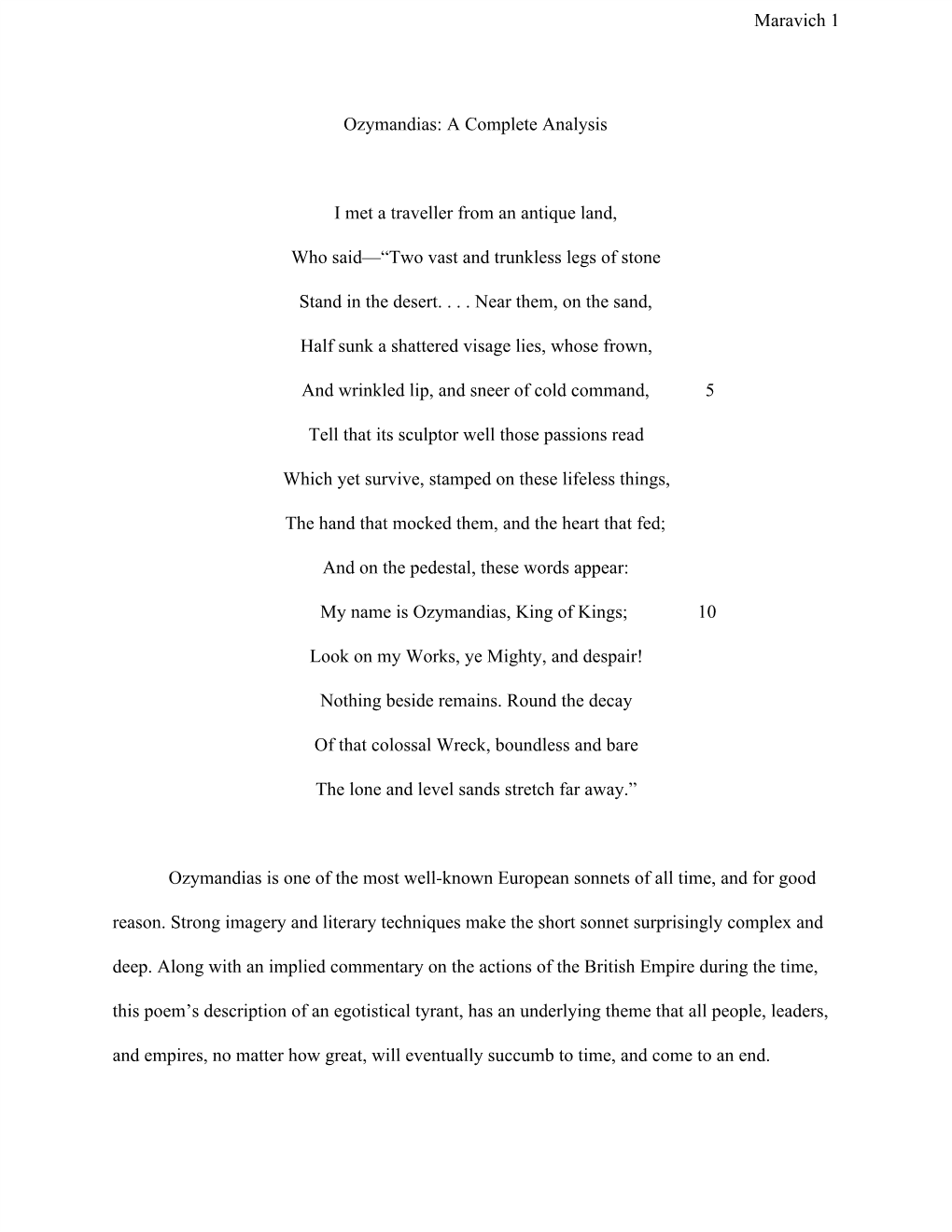

Ozymandias by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Ozymandias by Percy Bysshe Shelley I met a traveler from an antique land Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand, Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown, And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed; And on the pedestal these words appear: “My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look upon my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away. Detailed Analysis of the Poem: This sonnet composed in 1817 is probably Shelley’s most famous and most anthologized poem—which is somewhat strange, considering that it is in many ways an atypical poem for Shelley, and that it touches little upon the most important themes in his oeuvre at large (beauty, expression, love, imagination). Still, “Ozymandias” is a masterful sonnet. Essentially it is devoted to a single metaphor: the shattered, ruined statue in the desert wasteland, with its arrogant, passionate face and monomaniacal inscription (“Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”). The once-great king’s proud boast has been ironically disproved; Ozymandias’s works have crumbled and disappeared, his civilization is gone, all has been turned to dust by the impersonal, indiscriminate, destructive power of history. The ruined statue is now merely a monument to one man’s hubris, and a powerful statement about the insignificance of human beings to the passage of time. -

National Trauma and Romantic Illusions in Percy Shelley's the Cenci

humanities Article National Trauma and Romantic Illusions in Percy Shelley’s The Cenci Lisa Kasmer Department of English, Clark University, Worcester, MA 01610, USA; [email protected] Received: 18 March 2019; Accepted: 8 May 2019; Published: 14 May 2019 Abstract: Percy Shelley responded to the 1819 Peterloo Massacre by declaring the government’s response “a bloody murderous oppression.” As Shelley’s language suggests, this was a seminal event in the socially conscious life of the poet. Thereafter, Shelley devoted much of his writing to delineating the sociopolitical milieu of 1819 in political and confrontational works, including The Cenci, a verse drama that I argue portrays the coercive violence implicit in nationalism, or, as I term it, national trauma. In displaying the historical Roman Cenci family in starkly vituperous manner, that is, Shelley reveals his drive to speak to the historical moment, as he creates parallels between the tyranny that the Roman pater familias exhibits toward his family and the repression occurring during the time of emergent nationhood in Hanoverian England, which numerous scholars have addressed. While scholars have noted discrete acts of trauma in The Cenci and other Romantic works, there has been little sustained criticism from the theoretical point of view of trauma theory, which inhabits the intersections of history, cultural memory, and trauma, and which I explore as national trauma. Through The Cenci, Shelley implies that national trauma inheres within British nationhood in the multiple traumas of tyrannical rule, shored up by the nation’s cultural memory and history, instantiated in oppressive ancestral order and patrilineage. Viewing The Cenci from the perspective of national trauma, however, I conclude that Shelley’s revulsion at coercive governance and nationalism loses itself in the contemplation of the beautiful pathos of the effects of national trauma witnessed in Beatrice, as he instead turns to a more traditional national narrative. -

Shelley's Hellas and the Mask of Anarchy Are Thematically, Linguistically

63 Percy Bysshe Shelley, the Newspapers of 1819 and the Language of Poetry Catherine Boyle This essay rediscovers the link between the expatriate newspaper Gali- gnani’s Messenger and Shelley’s 1819 political poetry, particularly The Mask of Anarchy and Song, To the Men of England. It is suggested that a reading of this newspaper helps us to understand Shelley’s response to the counter-revolutionary press of his day; previous accounts have tended to solely stress Shelley’s allegiance to Leigh Hunt’s politics. As well as being a contribution to book history, this essay highlights the future of the nine - teenth-century book by exploring the ways the ongoing digitization of nine - teenth-century texts can enable new readings of familiar texts. It also covers some theoretical issues raised by these readings, namely the development of the Digital Humanities and intertextual theory. I must trespass upon the forgiveness of my readers for the display of newspaper erudition to which I have been reduced. Percy Bysshe Shelley, Preface to Hellas, 1821 1 helley’s Hellas and The Mask of Anarchy are thematically, linguistically, and compositionally related , and these resemblances can lead into a close S reading of Shelley’s 1819 political poetry. Both feature revolutions: an actual Greek revolution that had already occurred, and the putative revolution after the events of the Peterloo Massacre in 1819. Both mythologize historical events. In Hellas , the figure of the Jew Ahasuerus, doomed to wander the earth eternally, appears amidst an account of historical events. In The Mask of Anarchy Shelley inserts an apocalyptic, ungendered Shape which enacts the downfall of Anarchy. -

England in 1819 by Percy Bysshe Shelley DDE Programme: B.A

England in 1819 By Percy Bysshe Shelley DDE Programme: B.A. General Class: B.A. Part-I MS. SANGEETA SETHI DIRECTORATE OF DISTANCE EDUCATION Subject: KURUKSHETRA UNIVERSITY, English KURUKSHETRA Paper No. A Lesson No. 2 Introduction This presentation illustrates Shelley’s sonnet ‘England in 1819’. The poem is a description of prevalent political and economic conditions of England. The year 1819, is a disgusting reminder of the Peterloo massacre. The sonnet is a political satire, it reflects the poet’s concern for liberty; his aversion to Monarchy and his belief in love and restoration of common man’s dignity. Contents 1. Introduction, 2. Objectives 3. Paraphrase, 4. Questions Objectives This presentation will enable you to: 1. Understand the text of the poem. 2. Study explanation contained in the lesson script No. 25, B.A. I English 3. Know the visionary and the idealist in Shelley who condemned the oppressive institution of Monarchy and passionately hoped that a new era of stability, equality and justice would restore human dignity. 4. Form your opinion about the age and the social order and its conflicts. 5. Equip yourself with skill to perform in examination situation. About the poet A leading poet of the Romantic Movement, a revolutionary, Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792- 1822) was born to Timothy Shelley, a member of Parliament and highly respectable Sussex squire. After his education at Syon House Academy and Eton, he went to Oxford University in 1810. He was expelled from Oxford for Publishing a pamphlet under the provocative title ‘The Necessity of Atheism’. Shelley’s literary and political spirit of rebellion is reflected in his poems. -

SPECIAL ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS P.B. Shelley's Poem Ozymandias In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Space and Culture, India Zhatkin and Ryabova. Space and Culture, India 2019, 7:1 Page | 56 https://doi.org/10.20896/saci.v7i1.420 SPECIAL ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS P.B. Shelley’s Poem Ozymandias in Russian Translations Dmitry Nikolayevich Zhatkin †*and Anna Anatolyevna RyabovaÌ Abstract The article presents a comparative analysis of Russian translations of P.B.Shelley’s poem Ozymandias (1817), carried out by Ch. Vetrinsky, A.P. Barykova, K.D. Balmont, N. Minsky, V.Ya. Bryusov in 1890 – 1916. These translations fully reflect the peculiarities of the social and political, cultural and literary life in Russia of the late 19th – early 20th Centuries, namely weakening of the political system, growing of interest to the culture of Ancient Egypt, and strengthening of Neoromanticism in opposition to Naturalism in literature. In the process of the analysis, we used H. Smith’s sonnet Ozymandias, P.B. Shelley’s sonnet Ozymandias and its five Russian translations. The methods of historical poetics of A.N. Veselovsky, V.M. Zhirmunsky and provisions of the linguistic theory of translation of A.V. Fedorov were used. The article will be interesting for those studying literature, languages, philology. Keywords: P.B. Shelley, Ozymandias, Poetry, Literary Translation, Russian-English Literary Relations † Penza State Technological University, Penza, Russia * Corresponding Author, Email: [email protected], [email protected] Ì Email: [email protected] © 2019 Zhatkin and Ryabova. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Shelley in the Transition to Russian Symbolism

SHELLEY IN THE TRANSITION TO RUSSIAN SYMBOLISM: THREE VERSIONS OF ‘OZYMANDIAS’ David N. Wells I Shelley is a particularly significant figure in the early development of Russian Symbolism because of the high degree of critical attention he received in the 1880s and 1890s when Symbolism was rising as a literary force in Russia, and because of the number and quality of his translators. This article examines three different translations of Shelley’s sonnet ‘Ozymandias’ from the period. Taken together, they show that the English poet could be interpreted in different ways in order to support radically different aesthetic ideas, and to reflect both the views of the literary establishment and those of the emerging Symbolist movement. At the same time the example of Shelley confirms a persistent general truth about literary history: that the literary past is constantly recreated in terms of the present, and that a shared culture can be used to promote a changing view of the world as well as to reinforce the status quo. The advent of Symbolism as a literary movement in Russian literature is sometimes seen as a revolution in which a tide of individualism, prompted by a crisis of faith at home, and combined with a new sense of form drawing on French models, replaced almost overnight the positivist and utilitarian traditions of the 1870s and 1880s with their emphasis on social responsibility and their more conservative approach to metre, rhyme and poetic style.1 And indeed three landmark literary events marking the advent of Symbolism in Russia occurred in the pivotal year of 1892 – the publication of Zinaida Vengerova’s groundbreaking article on the French Symbolist poets in Severnyi vestnik, the appearance of 1 Ronald E. -

![[SD0]= Livre Free Zastrozzi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4345/sd0-livre-free-zastrozzi-1974345.webp)

[SD0]= Livre Free Zastrozzi

Register Free To Download Files | File Name : Zastrozzi PDF ZASTROZZI Tapa blanda 22 marzo 2020 Author : It's OK it is interesting to read and entertaining. The style is quite pompous, which is normal for many novels of its time, but it is not a boring book at all. However, there is nothing more than that! I recommend it, but don't expect something spectacular with great suspence and pathos. There is very little Gothic flavour in this simple novel, in my opinion. Flawed but simultaneously completely perfect Zastrozzi: A Romance is a Gothic novel by Percy Bysshe Shelley first published in 1810 in London by George Wilkie and John Robinson anonymously, with only the initials of the author's name, as "by P.B.S.". The first of Shelley's two early Gothic novellas, the other being St. Irvyne, outlines his atheistic worldview through the villain Zastrozzi and touches upon his earliest thoughts on ... Zastrozzi: A Romance: With Geff Francis, Mark McGann, Tilda Swinton, Hilary Trott. An adaptation of Shelley's Gothic novel, presented as a contemporary romance. Zastrozzi, A Romance was first published in 1810 with only the author's initials "P.B.S." on its title page. Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote it when he was seventeen while at Eton College. it was the first of Shelley's two early Gothic novels and considered to be his first published prose work as well. Zastrozzi: A Romance (1810) is a Gothic horror novel masterpiece by Percy Bysshe Shelley. Zastrozzi was the first publushed work by Shelley in 1810. He wrote Zastrozzi when he was seventeen and a student at Eton. -

Nonviolence As Response to Oppression and Repression in the Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley

Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2020, 8, 530-554 https://www.scirp.org/journal/jss ISSN Online: 2327-5960 ISSN Print: 2327-5952 “Ye Are Many, They Are Few”: Nonviolence as Response to Oppression and Repression in the Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley George Ewane Ngide Department of English, University of Yaoundé I, Yaoundé, Cameroon How to cite this paper: Ngide, G. E. (2020). Abstract “Ye Are Many, They Are Few”: Nonviolence as Response to Oppression and Repression This article sets out to examine the relationship between the government and in the Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Open the governed in the works of Percy Bysshe Shelley. We posit that such a rela- Journal of Social Sciences, 8, 530-554. tionship is generally characterised by oppression and repression of the go- https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.86039 verned (the people, the many) by the government (the few, the ruling class). Received: April 27, 2020 The ruling class inflicts pain of untold proportion on the masses that they Accepted: June 27, 2020 subordinate and subjugate. As a result of the gruesome pain inflicted on them Published: June 30, 2020 and the harrowing and excruciating experiences they go through, the masses Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and are obliged to stand in defiance of the system and through nonviolence tech- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. niques they overthrow the governing class. This overthrow does not lead to a This work is licensed under the Creative dictatorship of the proletariat rather it leads to a society of harmonious living. Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). -

Ozymandias-Litcharts

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com Ozymandias POEM TEXT THEMES 1 I met a traveller from an antique land, THE TRANSIENCE OF POWER 2 Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone One of Shelley’s most famous works, “Ozymandias” 3 Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand, describes the ruins of an ancient king’s statue in a 4 Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown, foreign desert. All that remains of the statue are two “vast” 5 And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, stone legs standing upright and a head half-buried in sand, along with a boastful inscription describing the ruler as the 6 Tell that its sculptor well those passions read “king of kings” whose mighty achievements invoke awe and 7 Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, despair in all who behold them. The inscription stands in ironic 8 The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed; contrast to the decrepit reality of the statue, however, 9 And on the pedestal, these words appear: underscoring the ultimate transience of political power. The 10 My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings; poem critiques such power through its suggestion that both 11 Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! great rulers and their kingdoms will fall to the sands of time. 12 Nothing beside remains. Round the decay In the poem, the speaker relates a story a traveler told him 13 Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare about the ruins of a “colossal wreck” of a sculpture whose 14 The lone and level sands stretch far away.” decaying physical state mirrors the dissolution of its subject’s—Ozymandias’s—power. -

Views, Playbills, Prompt Books Or Practitioner Interviews

Staging the Shelleys: A Case Study in Romantic Biodrama by Brittany Reid A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies University of Alberta © Brittany Reid, 2018 ii Abstract Although it has been nearly two hundred years since they lived and wrote, Romantic writers Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley continue to haunt the theatre in the twenty-first century. However, it is not only their plays, poems, and novels that have been adapted for the modern stage. Beginning in the twentieth century, renewed interest in the Shelleys’ lives led to the composition of numerous biographical plays based on Mary and Percy’s personal and creative partnership. But while these nineteenth-century writers enjoyed particular moments of such interest in the 1980s, the early twenty-first century has seen this interest flourish like never before. Consequently, the turn of the twenty-first century coincided with an unprecedented increase in the number and variety of plays about the Shelleys’ lives, writing, and literary legacies. As a testament to this recent resurgence, more than twenty theatrical adaptations of the Shelleys have been created and staged in the last twenty years. But although these plays continue to feature both Shelleys, most contemporary biographical plays about the couple now privilege Mary as their focal figure and prioritize her life, writing, and perspective. In this way, these plays represent a creative corollary of a broader cultural shift in interest from Percy to Mary as a biographical subject, which was first initiated in the 1980s through the recovery efforts of Mary Shelley scholars. -

The Timelessness of Art As Epitomized in Shelley's "Ozymandias"

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 5 No. 1; February 2014 Copyright © Australian International Academic Centre, Australia The Timelessness of Art as Epitomized in Shelley’s Ozymandias Krishna Daiya Government Engineering College, Rajkot E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.5n.1p.154 Received: 05/01/2014 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.5n.1p.154 Accepted: 27/02/2014 Abstract Percy Bysshe Shelley was a poet whose name itself is a Metaphor for exquisite, rhythmic poetry laden with images of Nature as well as Man. He possesses the magical power of transporting the reader into an alternative world with the unique use of metaphors and imagery. His personal sadness was translated into sweet songs that are echoed in the entire world defying all boundaries and straddles. One of the most renowned works of Shelley, Ozymandias is a sonnet that challenges the claims of the emperors and their empires that they are going to inspire generations to come. It glorifies the timelessness of art. The all-powerful Time ruins everything with its impersonal, indiscriminate and destructive power. Civilisations and empires are wiped out from the surface of the earth and forgotten but there is something that outlasts these things and that is art. Eternity can be achieved by the poet’s words, not by the ruler’s will to dominate. Keywords: Art, Civilizations, Empires, Eternity, Time 1. Introduction The period from the last decade of the eighteenth century to the opening decades of the nineteenth century is an era of revolutionary social changes in all fields, economic, political, religious and literary. -

Shelley's Unknown Eros: Post-Secular Love in Epipsychidion

religions Article Shelley’s Unknown Eros: Post-Secular Love in Epipsychidion Michael Tomko Department of Humanities, Villanova University, Villanova, PA 19085, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-610-519-3017 Academic Editor: Kevin Hart Received: 3 June 2016; Accepted: 5 September 2016; Published: 14 September 2016 Abstract: Whether Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Epipsychidion—a Platonic poem on love addressed to the patriarchally imprisoned Theresa Viviani or “Emily”—receives praise or blame has generally been determined by two focal passages: a secular sermon on free love and a planetary allegorical thinly veiling his own imbroglio. This essay re-reads Shelley’s 1821 work drawing on two recent arguments: Stuart Curran’s Dantean call to take the poem’s Florentine narrator seriously as a character, not just as an autobiographical cypher, and Colin Jager’s outline of Shelley’s move beyond the assumptions of his professed atheism after 1816. Based on the poem’s structure and imagery, the paper argues that Epipsychidion critiques the false sense of revolutionary ascent and dualistic escape offered to Emily, who is commodified and erased by the narrator’s egocentric, “counterfeit divinization of eros” (Benedict XVI). Turning from this Radical Enlightenment Platonism, the poem momentarily realizes an embodied, hylomorphic romantic union akin to the Christian nuptial mystery of two becoming “one flesh” (Mark 10:8). This ideal, however, collapses back into solipsism when the narrator cannot understand or accept love as a “unity in duality” (Benedict XVI). This paper thus claims Epipsychidion as a post-secular inquiry into the problem of love whose philosophic limits and theological horizons are both surprising and instructive.