An Investigation of Monetization Strategies in Aaa Video Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Step Back Into the Octagon with EA SPORTS UFC 3

February 2, 2018 Step Back Into the Octagon With EA SPORTS UFC 3 All New G.O.A.T. Career Mode, Combined with Real Player Motion Tech Delivers the Most Realistic MMA Game Ever Created Watch the Worldwide Launch Trailer Here REDWOOD CITY, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ: EA) today launched EA SPORTS UFC 3, bringing the thrill of mixed martial arts back to consoles with new gameplay features and animations, new social modes to challenge friends, and a new G.O.A.T. Career mode that delivers excitement both inside and outside of UFC's world-famous Octagon®. UPROXX calls EA SPORTS UFC 3 "Intense fun," and Bleacher Reports states it "Plays like a dream." This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180202005064/en/ "EA SPORTS UFC 3 is the most realistic mixed martial arts game ever made," UFC President Dana White said. "The new G.O.A.T. Career Mode gives you the opportunity to go from contender to champion by promoting your brand and performing inside the Octagon. This game has it all." "We've completely reinvented our striking game with Real Player Motion Tech, and we think fans are really going to love it," said EA SPORTS UFC 3 Creative Director, Brian Hayes. "We've also incorporated a lot of fan feedback in the new G.O.A.T. Career mode, and throughout the whole game. It's great to be back after two years working on this amazing game." Step Back Into the Octagon With EA SPORTS UFC 3 (Graphic: Business Wire) Real Player Motion (RPM) Tech is a revolutionary new EA SPORTS animation technology that sets a new bar for motion and responsiveness in the best-looking - and now the best-feeling - EA SPORTS UFC game ever. -

Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report

Merrimack College Merrimack ScholarWorks Honors Senior Capstone Projects Honors Program Spring 2016 Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report Brian Nelson Goncalves Merrimack College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_capstones Part of the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation Goncalves, Brian Nelson, "Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report" (2016). Honors Senior Capstone Projects. 7. https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_capstones/7 This Capstone - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Merrimack ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Merrimack ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. EQUITY ANALYST REPORT 1 Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Equity Analyst Report Brian Nelson Goncalves Merrimack College Honors Department May 5, 2016 Author Notes Brian Nelson Goncalves, Finance Department and Honors Program, at Merrimack Collegei. Brian Nelson Goncalves is a Senior Honors student at Merrimack College. This report was created with the intent to educate investors while also serving as the students Senior Honors Capstone. Full disclosure, Brian is a long time share holder of Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. 1 Running Head: TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. EQUITY ANALYST REPORT 2 Table of Contents -

Future Division 10 Receive the Award

〈Press Release〉 September 18, 2016 Future Division 10 Receive the Award Voted by visitors of the TOKYO GAME SHOW 2016! Title with future prospective is selected! Computer Entertainment Supplier’s Association Japan Game Awards 2016 (JGA 2016), organized by the Computer Entertainment Supplier’s Association (CESA; Chairman: Hideki Okamura), has today selected and announced 10 award winners for the Japan Game Awards “Future Division” Award. The award for the Future Division is applicable for all titles that were announced and exhibited at the TOKYO GAME SHOW 2016, and votes were collected from visitors in three days during the event from September 15 (Thu) to 17 (Sat). After which, through a screening by the Japan Game Awards Selection Committee of works that received high anticipation of launch and overwhelming support, the game with the best future prospect was selected. - Japan Game Awards 2016 “Future Division” Award Winner – *Alphabetical order Title Company Platform FINAL FANTASY XV SQUARE ENIX CO., LTD. PS4/PSVR / Xbox One GRAVITY RUSH 2 Sony Interactive Entertainment Inc. PS4 Horizon Zero Dawn Sony Interactive Entertainment Inc. PS4 megami meguri CAPCOM CO., LTD. 3DS MONSTER HUNTER STORIES CAPCOM CO., LTD. 3DS Nioh KOEI TECMO GAMES CO., LTD. PS4 PS4/PSVR / Xbox One / Resident Evil 7 CAPCOM CO., LTD. PC SUMMER LESSON : BANDAI NAMCO Entertainment Inc. PSVR HIKARI M-Seven Days Room The Last Guardian Sony Interactive Entertainment Inc. PS4 Ryu ga Gotoku 6 SEGA Games Co., Ltd. PS4 ※Platform abbreviations:PS4: PlayStation®4 / PSVR: PlayStation®VR / 3DS: Nintendo 3DS and 3DS LL / PC: Windows® “Japan Game Awards” official website:http://awards.cesa.or.jp/en/ *photos of the award ceremony: https://www.filey.jp/tgs/ (ID: tgs_press, PW: press_tgs) *prize logos: http://awards.cesa.or.jp/prize-mark/index.html ■For inquiries from the press: TOKYO GAME SHOW Management Office Press Room: Fax: +81-3-5575-3222 / e-mail:[email protected] . -

Redeye-Gaming-Guide-2020.Pdf

REDEYE GAMING GUIDE 2020 GAMING GUIDE 2020 Senior REDEYE Redeye is the next generation equity research and investment banking company, specialized in life science and technology. We are the leading providers of corporate broking and corporate finance in these sectors. Our clients are innovative growth companies in the nordics and we use a unique rating model built on a value based investment philosophy. Redeye was founded 1999 in Stockholm and is regulated by the swedish financial authority (finansinspektionen). THE GAMING TEAM Johan Ekström Tomas Otterbeck Kristoffer Lindström Jonas Amnesten Head of Digital Senior Analyst Senior Analyst Analyst Entertainment Johan has a MSc in finance Tomas Otterbeck gained a Kristoffer Lindström has both Jonas Amnesten is an equity from Stockholm School of Master’s degree in Business a BSc and an MSc in Finance. analyst within Redeye’s tech- Economic and has studied and Economics at Stockholm He has previously worked as a nology team, with focus on e-commerce and marketing University. He also studied financial advisor, stockbroker the online gambling industry. at MBA Haas School of Busi- Computing and Systems and equity analyst at Swed- He holds a Master’s degree ness, University of California, Science at the KTH Royal bank. Kristoffer started to in Finance from Stockholm Berkeley. Johan has worked Institute of Technology. work for Redeye in early 2014, University, School of Business. as analyst and portfolio Tomas was previously respon- and today works as an equity He has more than 6 years’ manager at Swedbank Robur, sible for Redeye’s website for analyst covering companies experience from the online equity PM at Alfa Bank and six years, during which time in the tech sector with a focus gambling industry, working Gazprombank in Moscow he developed its blog and on the Gaming and Gambling in both Sweden and Malta as and as hedge fund PM at community and was editor industry. -

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

Gambling and Video Games: Are Esports Betting and Skin Gambling Associated with Greater Gambling Involvement and Harm?

RESEARCH REPORT Gambling and video games: are esports betting and skin gambling associated with greater gambling involvement and harm? July 2020 responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au © Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, July 2020 This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs, branding or logos. This report has been peer reviewed by two independent researchers. For further information on the foundation’s review process of research reports, please see responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au. For information on the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation Research Program visit responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au. Disclaimer The opinions, findings and proposals contained in this report represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the attitudes or opinions of the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation or the State of Victoria. No warranty is given as to the accuracy of the information. The Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation specifically excludes any liability for any error or inaccuracy in, or omissions from, this document and any loss or damage that you or any other person may suffer. Conflict of interest declaration The authors declare no conflict of interest in relation to this report or project. To cite this report Greer, N, Rockloff, M, Russell, Alex M. T., 2020, Gambling and video games: are esports betting and skin gambling associated with greater gambling involvement and harm?, Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, -

Investor Update 01/13/2015 Gamestop Overview

Investor Update 01/13/2015 GameStop Overview EUROPE 331 CANADA stores 1,321 stores UNITED STATES 4,656 stores 421 stores AUSTRALIA/NZ Italy 420 Ireland 50 France 435 Total Stores: 6,729 Germany 260 6,248 Video game stores Nordic 156 481 Technology Brand stores 2 Video Game Brands Platform Overview GameStop maintains a leadership position in the $22.4bn worldwide gaming market 30-34% next-gen console market share (U.S.) 48-52% next-gen software market share (U.S.) Leading retailer in the fast growing digital business (26%+ CAGR from 2011-2013) Unique in-store customer experience Highly successful loyalty program with 40 million global members Game Informer is the #1 digital magazine globally Established buy-sell-trade program drives differentiation from competitors and enhanced profitability 3 GameStop’s Unique Formula Informed Associates Multichannel Vendor Relationships PowerUp Rewards GameInformer Magazine Buy – Sell – Trade 4 Our Strategic Plan Maximize Brick & Mortar Stores . Capture leading market share of new console cycle . Utilize stores to grow digital sales . Apply retail expertise to Tech Brands Build on our Distinct Pre-owned Business . Expand the value assortment to increase sales and gross profit dollars . Gain market share in Value channel Own the Customer . Capitalize on our international loyalty program, now with 40 million members in 14 countries around the world Digital Growth . DLC, Kongregate, Steam wallet, PC Downloads, Console Network cards Disciplined Capital Allocation . Return 100% of our FCF to shareholders through buyback and dividend unless a better opportunity arises 5 We are delivering on our plan… . Digital & Mobile growth . $2.69B of digital receipts and $989M of mobile revenue since 2011 . -

An Educator's Guide to Gaming

EDUCATOR RESOURCE VIDEO GAME TERMS GLOSSARY An Educator’s Guide to Gaming Gambling in games has a language all its own. Here are some words you need to know. 1-up Power-Up An object that gives the player an extra life (or try) in games Objects that instantly benefit or add extra abilities to where the player has a limited number of chances to complete the game character, usually as a temporary effect. a game, a task, or level. 1-ups can be acheived by completing Persistent power-ups are called perks. Power-Ups levels or found in purchased loot boxes. can be acheived by completing levels or found in purchased loot boxes. 100% A game is 100% complete once a player unlocks all available Season content and completes the game. The player must collect 1. The full set of downloadable content that is every in-game item, upgrade, and complete every mission to planned to be added to a video game, which can get 100%. Many players are so determined to get 100%, that be entirely purchased with a season pass. they will make mulitiple in-game purchases for upgrades to 2. A finite period of time in massive multiplayer achieve this goal. online games in which new content, such as themes, rules, and modes, becomes available – Downloadable Content (DLC) sometimes replacing prior time-limited content. Additional content for a video game that is acquired through a Notable games that use this “season” system digital delivery system. DLCs can be purchased in video game include Star Wars: Battlefront II (2017) and console stores. -

Exploiting Steam Lobbies and Matchmaking by Luigi Auriemma

Revision 1 EXPLOITING STEAM LOBBIES AND MATCHMAKING BY LUIGI AURIEMMA Description of the security vulnerabilities that affected the Steam lobbies and all the games using the Steam Matchmaking functionalities. TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Introduction ______________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Steam lobbies and security risks _______________________________________________________________________ 2 Description of the issues ________________________________________________________________________________ 4 The proof-of-concept ____________________________________________________________________________________ 7 FAQ ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 8 History ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 9 Company Information __________________________________________________________________________________ 10 INTRODUCTION Introduction STEAM "Steam1 is an internet-based digital distribution, digital rights management, multiplayer, and communications platform developed by Valve Corporation. It is used to distribute games and related media from small, independent developers and larger software houses online."2 It's not easy to define Steam because it's not just a platform for buying games but also a social network, a market for game items, a framework3 for integrating various functionalities in games, an anti-cheat, a cloud and more. But the most important and attractive -

Pdf (Accessed 2.10.14)

Notes 1 Introduction: Video Games and Storytelling 1. It must be noted that the term ‘Narratological’ is a rather loose application by the Ludologists and the implications of this are pointed out later in this chapter. 2. Roland Barthes states that the ‘infinity of the signifier refers not to some idea of the ineffable (the unnameable signified) but to that of a playing [ ...] theText is plural’. Source: Barthes, R., 1977. Image, Music, Text, in: Heath,S.(Tran.), Fontana Communications Series. Fontana, London. pp. 158–159. 3.In Gaming Globally: Production, Play, and Place (Huntemann and Aslinger, 2012),theeditors acknowledgethat ‘while gaming maybe global, gaming cultures and practices vary widely depending on the power and voice of var- ious stakeholders’ (p. 27). The paucity of games studies scholarship coming from some of the largest consumers of video games, such as South Korea, China and India, to name a few, is markedly noticeable. The lack of represen- tation of non-Western conceptions of play culture and storytelling traditions is similarly problematic. 4. Chapter 8 will engage with this issue in more detail. 5. ‘(W)reading’ is preferred over the more commonly used neologism ‘wread- ing’toemphasise the supplementarity of the reading and writingprocesses and also to differentiate it from earlier usage that might claim that the two processes are the same thing. 3 (W)Reading the Machinic Game-Narrative 6. For whichhe is criticisedby Hayles (see Chapter 2). 7. Landow respondstothis by rightly stating that Aarseth misreads his original comment where heclaims that ‘the reader whochooses among linksortakes advantage of Storyspace’s hypertext capabilities shares some of the power of theauthor’(Landow, p. -

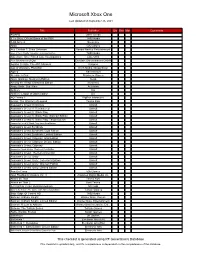

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Magisterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MAGISTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Magisterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „Player Characters in Plattform-exklusiven Videospielen“ verfasst von / submitted by Christof Strauss Bakk.phil. BA BA MA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2019 / Vienna 2019 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / UA 066 841 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Magisterstudium Publizistik- und degree programme as it appears on Kommunikationswissenschaft the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: tit. Univ. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Duchkowitsch 1. Einleitung ....................................................................................................................... 1 2. Was ist ein Videospiel .................................................................................................... 2 3. Videospiele in der Kommunikationswissenschaft............................................................ 3 4. Methodik ........................................................................................................................ 7 5. Videospiel-Genres .........................................................................................................10 6. Geschichte der Videospiele ...........................................................................................13 6.1. Die Anfänge der Videospiele ..................................................................................13